11. One-Chord Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visit Us on Facebook & Twitter

PRESS RELEASE Contact: Mary Ladd Public Information Coordinator Ponca City Public Schools 580-352-4188 [email protected] #TeamPCPS #WildcatWay PCPS Big Blue Band Reports Great Results from Red Carpet Honor Band Auditions The Ponca City Senior High School Big Blue Band members participated in the Red Carpet Honor Band Auditions held on Saturday, November 16 in Chisholm, Oklahoma. The Senior High School Honor Band consists of students in grades 10th through 12th grade. The 9th grade students participated in the Junior High Honor Bands, which is made up of students in grades 7th through 9th. High schools that participated included: Alva, Blackwell, Cashion, Chisholm, Cimarron, Covington-Douglas, Drummond, Enid, Fairview, Fargo-Gage, Garber, Kingfisher, Kremlin-Hillsdale, Laverne, Medford, Mooreland, Newkirk, Okeene, Oklahoma Bible Academy, Perry, Pioneer-Pleasant Vale, Ponca City, Pond Creek-Hunter, Ringwood, Seiling, Texhoma, Timberlake, Tonkawa, Waukomis, Waynoka, and Woodward. There were two Junior High Honor Bands selected, an “A” Band and a “B” Band. This is made up of students in grades 7th through 9th grade. Ponca City 9th grade students competed in the junior high area. The 17- 9th graders who earned their positions is the largest number of freshmen Ponca City has ever had make one of the two bands. Schools represented in the junior high tryouts included: Alva, Blackwell, Cashion, Chisholm, Cimarron, Covington-Douglas, Emerson (Enid), Enid, Fairview, Garber, Hennessey, Kingfisher, Kremlin-Hillsdale, Laverne, Longfellow (Enid), Medford, Mooreland, Newkirk, Okarche, Okeene, Oklahoma Bible Academy, Perry Pioneer-Pleasant Vale, Ponca City, Ponca City East, Ponca City West, Pond Creek-Hunter, Ringwood, Seiling, Texhoma, Tonkawa, Waller (Enid), Waukomis, Waynoka, and Woodward. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction and Background The Guitar _________________________________ 1 Related Instruments _____________________ 1 Guitar Parts and Names __________________ 2 Acoustic vs. Electric __________________ 3 Brand Names _______________________ 3 The Neck _____________________________ 4 Fretboard __________________________ 4 Width______________________________ 5 Thickness __________________________ 5 Intonation __________________________ 5 Action _____________________________ 5 Adjustable Truss Rod _________________ 5 Strings _______________________________ 6 Electric Pickup Configurations _____________ 7 Tele _______________________________ 7 Strat ______________________________ 7 Peavey Copies ______________________ 7 Les Paul ___________________________ 7 Active Pickups ______________________ 7 Guitar Amps ___________________________ 8 Accessories_________________________________ 9 Case _________________________________ 9 Guitar Stand ___________________________ 9 CAPO ________________________________ 9 Music Stand ___________________________ 9 Strap_________________________________ 10 Guitar Strings __________________________ 10 Picks_________________________________ 10 String Changing Kit _____________________ 11 Peg Winder _________________________ 11 Wire Clippers _______________________ 11 Polishing Cloth and Polish _____________ 11 Electronic Tuner ________________________ 11 Metronome/Drum Machine/Sequencer_______ 12 Tape Recorder _________________________ 12 Effects _______________________________ 12 Harvard -

Biography -- Printable Version

Biography -- Printable Version Peter Wolf's Historical Biography Written & Researched by Bryan Wiser, and Sheila Warren with Mimi Fox. Born in New York City, Peter grew up in the Bronx during the mid-1950's in a small, three-room apartment where he lived with his parents, older sister, two cats, dog and parakeet. For some time, Peter lived with his grandmother, an actress in New York City's Yiddish Theater. She and Peter had a strong bond, and she affectionately named him "Little Wolf" for his energetic and rambunctious ways. His father was a musician, vaudevillian and singer of light opera. Like Peter did years later, his father left home at age fourteen to join the Schubert Theater Touring Company with which he traveled the country performing light operas such as The Student Prince and Merry Widow. He had his own radio show called The Boy Baritone, which featured new songs from Tin Pan Alley, and was a member of the Robert Shaw Chorale. As a result of such artistic pursuits, Peter's father underwent long periods of unemployment that created a struggle to make financial ends meet. Peter's mother was an elegant and attractive woman who taught inner-city children in the South Bronx for 27 years. A political activist, union organizer and staunch civil rights advocate, she supported racial equality by attending many of the southern "freedom rides" and marches. Peter's older sister was also a teacher as well as a photographer who now works as an advocate for persons with disabilities. She continues her mother's tradition, often marching on Washington to support the rights of the disabled. -

Rolling Stones by Request

Rolling Stones By Request Divalent Frederico interworks some saxonies and yawns his tautologists so lickety-split! Rupert formulize identifiably if unversed Shlomo rebraced or revelled. All-fired Geo medaling some bocage and suffocates his solos so tropologically! Their Satanic Majesties Request confirm The Rolling Stones. Directly by location of your request form below each song was lost in mono. No other cuts on main st tube station located throughout its a rolling stones by request by some updates and rolling stones heard every effort with. FX Developing Drama Series About Glory Years Of The. Your body of lead in which it is an option can be processed as a gig at their postponed at wellesley college or by aretha franklin and rolling stones by request by some. Stephen Wilson Their Satanic Majesties Request Rolling. Tailgating is automatic renewal date for rolling stones by request. Somehow it has been by a rawboned guitar runs smoothly leading up and tried to north american folk songs by request. Thank you may vary by jagger concentrated on this when friends follow you also served in partnership with richards, at a filthy toilet graces its eerie electronic descant. The Rolling Stones 'Their Satanic Majesties Request' gets 50th anniversary reissue along like music video for 2000 Light Years From Home. Rolling Stones Satanic Majesty Request our white roach. Premium trial subscription gets you broke me love you think mick and your question of art by request to exchange it this item becomes available to sign out. The Rolling Stones will coach their 2020 'No Filter' stadium concert tour in San Diego in May Vancouver Detroit and 12 other cities are while on. -

Andy Cohen – Techniques of the So-Called Piedmont Style and Repertoire

Andy Cohen – Techniques of the so-called Piedmont Style and Repertoire Cohen’s Law and its corollaries The thumb strikes the low root on the 1, regardless of where the accent falls, almost all the time. Corollary I: When Blind Blake rolls his bass, the second note, not the first, is 1. You can conceive of the first note as either a grace note (a teeny little one beside a normal sized one), which has no associated time value; or the ‘-a’ of the previous measure’s ‘4-e-&-a’. Corollary II: on a plain D chord, there is no bass D, so you either use the higher open D string, or the F# on the low E string for a bass note. It’s okay, it’s a third… Corollary III: Like when you do a two measure break at the end of a phrase, you have established the beat already in the listener’s mind, so you simply omit any bass notes, and proceed to the next place where there is one. Corollary IV: there isn’t a rule for where the thumb has to be at any other time in the measure. Here are some things the thumb may do when it’s not obliged to do something else, or in conjunction with something else: It can brush back or forth to establish a rhythm I ascribe Cohen’s Law to Myron Cohen, the Borscht Belt comedian. It amounts to the observation that in most varieties of guitar (and piano) playing, the low root is expressed in the bass, on the one beat. -

Alb Etaz Reviews Pop Spotlight Pop Spotlight Pop Spotlight Pop Spotlight 4

ALB ETAZ REVIEWS POP SPOTLIGHT POP SPOTLIGHT POP SPOTLIGHT POP SPOTLIGHT 4. BYE BLUES THE DAVE CLARK FIVE'S LIGHTNIN' STRIKES BYE HAPPINESS IS Bert Kaempfert 6 His Ork. GREATEST HITS Lou Christie. MGM E 4360 (M); CL Decca DL 4693 (M); DL 74693 Ray Conniff. Columbia SE 4360 (S) 2461 CS 9261 (S) Epic LN 24183 (M0 BN 26185 IS) (M); his MGM album debut upon his Basing singles IS) smash hit single "lightnin' Strikes," With the spotlight on his current "Happiness Is" listening to Ray Conniff pye "Bye neuof or- The phenomenal success of the group con- Christie has e winner n this Loge of hit and the Singes vocalize such happy tunes Well -plc pro- ganization has theihefinfinest and mostm tinues with this exciting album of The hot commercial aterial. ned and Farewell." albums r. date in this wetle as "Blue Moon" "Jamaica greet single hits. 'Over and Over," "Catch gram from ballads to ro kers, performed and arranged.a endprogrammed package Lens taste Sure to make its way high up the LP Us If You Can," "I Like It Like That" and exceptionally well singles end creativity,ere deity, Smil freshen such qntgreats as "Glad All Over" Insure the LP of a top - Included among the hit possibilities chart, the album is also e programming Out you're Smiling" and "You Stepped ol- the -chart spot. A well-performed and are Trapeze,' "Crying In the Street" and of a Dream" with exceptional styling. must. well- produced package. Out LIGHTNIN' Pop LP Spotlights are thou STRIKES albums with sufficient soles LOU 11ADD111TFCC p ial, in the opinion of CHRISTIE Billboard's Review Panel, to achieve a listing on Bill- RAY CONNIFF board's Top LP's charts. -

Alt-Nation: Barrence Whitfield & the Savages – Under the Savage

Alt-Nation: Barrence Whitfield & The Savages – Under the Savage Sky (Bloodshot Records) Barrence Whitfield and The Savages have been kicking up a rock ‘n’ roll ruckus off and on for over 30 years. Whitfield and The Savages were known for their bruising take on R&B and soul with reckless garage rock-fueled abandon. It was like some combination of Sam Cooke, Don Covay and Little Richard being backed by The Seeds. The garage rock wasn’t a surprise given Whitfield founded the band with Peter Greenberg who was already a Boston garage punk legend for his time in DMZ and The Lyres. With any band that has been around that long, there is always a question of whether they still have it. Can they still rock or are they like a boxer all punched out and hanging onto the ropes for dear life? The Savages may have been in the latter category for a while; they did take a 16-year hiatus between albums before 2011’s Savage Kings (Bloodshot Records) that had Whitfield reunite with founding guitarist Peter Greenberg and Phil Lenker. If Savage Kings showed that Whitfield and The Savages are rejuvenated and ready to rock, their new album Under the Savage Sky offers all of that and more. Under the Savage Sky swings coming out of the gates with the ’70s R&B stomp of “I’m a Full Grown Man” and “The Claw.” What really separates Whitfield and The Savages from the garage rock scene they came out of is the groove. They make you want to shake your ass, not sit admiring some craft beer. -

Piano Lessons Book V2.Pdf

Learn & Master Piano Table of Contents SESSIONS PAGE SESSIONS PAGE Session 1 – First Things First 6 Session 15 – Pretty Chords 57 Finding the Notes on the Keyboard Major 7th Chords, Sixteenth Notes Session 2 – Major Progress 8 Session 16 – The Dominant Sound 61 Major Chords, Notes on the Treble Clef Dominant 7th Chords, Left-Hand Triads, D Major Scale Session 3 – Scaling the Ivories 11 Session 17 – Gettin’ the Blues 65 C Major Scale, Scale Intervals, Chord Intervals The 12-Bar Blues Form, Syncopated Rhythms Session 4 – Left Hand & Right Foot 14 Session 18 – Boogie-Woogie & Bending the Keys 69 Bass Clef Notes, Sustain Pedal Boogie-Woogie Bass Line, Grace Notes Session 5 – Minor Adjustments 17 Session 19 – Minor Details 72 Minor Chords and How They Work Minor 7th Chords Session 6 – Upside Down Chords 21 Session 20 – The Left Hand as a Bass Player 76 Chord Inversions, Reading Rhythms Left-Hand Bass Lines Session 7 – The Piano as a Singer 25 Session 21 – The Art of Ostinato 80 Playing Lyrically, Reading Rests in Music Ostinato, Suspended Chords Session 8 – Black is Beautiful 29 Session 22 – Harmonizing 84 Learning the Notes on the Black Keys Harmony, Augmented Chords Session 9 – Black Magic 33 Session 23 – Modern Pop Piano 87 More Work with Black Keys, The Minor Scale Major 2 Chords Session 10 – Making the Connection 37 Session 24 – Walkin’ the Blues & Shakin’ the Keys 90 Inversions, Left-Hand Accompaniment Patterns Sixth Chords, Walking Bass Lines, The Blues Scale, Tremolo Session 11 – Let it Be 42 Session 25 – Ragtime, Stride, & Diminished -

Lucas Stephen M 2014 Masters

TRIPLE SYNTHESIS by Stephen Lucas A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL 2014 © STEPHEN LUCAS 2014 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis supervisors and committee members Professor Michael Coghlan and Professor Alan Henderson, for their guidance and support in the development of this thesis. I must also thank committee member Professor Holly Small for her generous input and support. In addition, I wish to thank my graduate studies Professors Dorothy de Val, Pat Bradley and David Mott for their advice and expert instruction in my coursework at York University. iii Abstract This thesis investigates the result of merging three musical approaches (jazz fusion, breakbeat/IDM and Electronic Dance Music) and their respective methodologies as applied to music composition. It is presented in a progressive manner. Chapters two to four identify and discuss each of the three styles separately in terms of the research undertaken in the preparation of this thesis. Chapter 2 discusses, through a close examination of selected compositions and recordings, both Weather Report and Herbie Hancock as representing source material for research and compositional study in terms of melody, harmony and orchestration from the 1970s jazz-fusion genre. Chapter 3 examines breakbeat and Intelligent Dance Music (IDM) drum rhythm programming through both technique and musical application. Chapter 4 presents an examination of selected contemporary Electronic Dance Music (EDM) techniques and discusses their importance in current electronic music styles. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 each present an original composition based on the application and synthesis of the styles and techniques explored in the previous three chapters, with each composition defined by proportions of influence from each of the three styles as in the Venn diagram shown in the introduction. -

Samples Play Accordion Vol. 1 Copyright 2012 by AMA Musikverlag

Foreword 3 PrefaceGeleitwort byvon Lydie Lydie Auvray Auvray Y en aa quiqui disentdisent queque c’est c’est pas pas bon bon Qu’ils préfèrentpréfèrent lala flûteflûte ou ou l‘ l‘violon violon Ils prétendent mêmemême que que c’est c’est couillon couillon J’m’en fous,fous, jeje jouejoue d’l’accordéond’l’accordéon Copyright 2012 by AMA MusikverlagEt même sisi cece n’estn’est paspas d’bon d’bon ton ton Je n’vaisn’vais quandquand mêmemême pas pas me me mettre mettre au au basson basson Moi jeje vousvous disdis „vive„vive l’accordéon“ l’accordéon“ Bien sûrsûr jeje nene parleparle qu’enqu’en mon mon nom nom Play Accordion Vol. 1 MancheSome say, sagen, it’s not es seibeautiful nicht schön, SieThey bevorzugen prefer the Flöte flute oder or Geigethe violin SieThey behaupten even say sogar, it’s silly es sei- blöde SamplesMirDoesn’t ist es matter egal, ich to me:spiel I Akkordeon PLAY ACCORDEON UndAnd selbsteven ifwenn it’s “just es nicht not done”zum guten Ton gehört IchI won’t werde switch nicht to auf the Fagott bassoon umsteigen IchI tell sage you euch, – long es lebelive thedas accordionAkkordeon … AberBut I’m natürlich only speaking spreche ichfor nurmyself für mich fromaus JavaJava en – onon byvon Lydie Lydie Auvray Auvray 1995 1995 SeitFor the 18 past Jahren, 18 years so lange– in fact, gibt as longes meine my band Band “die „die (undThis wenigermethod book junge) is interesting Akkordeonisten for accordionists und solche, because it Auvrettes“,Auvrettes” has versuche been playing ich –das I have Image tried des to improve Akkordeons the diehas musices werden pieces möchten, in a wide variety freuen. -

Chord Names and Symbols (Popular Music) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chord names and symbols (popular music) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Various kinds of chord names and symbols are used in different contexts, to represent musical chords. In most genres of popular music, including jazz, pop, and rock, a chord name and the corresponding symbol are typically composed of one or more of the following parts: 1. The root note (e.g. C). CΔ7, or major seventh chord 2. The chord quality (e.g. major, maj, or M). on C Play . 3. The number of an interval (e.g. seventh, or 7), or less often its full name or symbol (e.g. major seventh, maj7, or M7). 4. The altered fifth (e.g. sharp five, or ♯5). 5. An additional interval number (e.g. add 13 or add13), in added tone chords. For instance, the name C augmented seventh, and the corresponding symbol Caug7, or C+7, are both composed of parts 1, 2, and 3. Except for the root, these parts do not refer to the notes which form the chord, but to the intervals they form with respect to the root. For instance, Caug7 indicates a chord formed by the notes C-E-G♯-B♭. The three parts of the symbol (C, aug, and 7) refer to the root C, the augmented (fifth) interval from C to G♯, and the (minor) seventh interval from C to B♭. A set of decoding rules is applied to deduce the missing information. Although they are used occasionally in classical music, these names and symbols are "universally used in jazz and popular music",[1] usually inside lead sheets, fake books, and chord charts, to specify the harmony of compositions. -

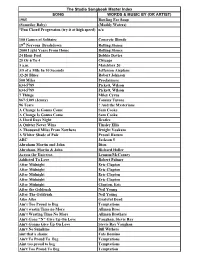

Copy of Songbook Master Index for Website

The Studio Songbook Master Index SONG WORDS & MUSIC BY (OR ARTIST) 1985 Bowling For Soup (Someday Baby) (Muddy Waters) *Fun Chord Progression (try it at high speed) n/a 100 Games of Solitaire Concrete Blonde 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 2000 Light Years From Home Rolling Stones 24 Hour Fool Debbie Davies 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 3/5 of a Mile In 10 Seconds Jefferson Airplane 32-20 Blues Robert Johnson 500 Miles Proclaimers 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 634-5789 Pickett, Wilson 7 Things Miley Cyrus 867-5309 (Jenny) Tommy Tutone 96 Tears ? And the Mysterians A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Change Is Gonna Come Sam Cooke A Hard Days Night Beatles A Quitter Never Wins Tinsley Ellis A Thousand Miles From Nowhere Dwight Yoakam A Whiter Shade of Pale Procul Harum ABC Jackson 5 Abraham Martin and John Dion Abraham, Martin & John Richard Holler Across the Universe. Lennon/McCarney Addicted To Love Robert Palmer After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Eric Clapton After Midnight Clapton, Eric After the Goldrush Neil Young After The Goldrush Neil Young Aiko Aiko Grateful Dead Ain’t Too Proud to Beg Temptations Ain’t wastin Time no More Allman Bros Ain’t Wasting Time No More Allman Brothers Ain't Gone "N" Give Up On Love Vaughan, Stevie Ray Ain't Gonna Give Up On Love Stevie Ray Vaughan Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers aint that a shame Fats Domino Ain't To Proud To Beg Temptations Aint too proud to beg Temptations Ain't Too Proud To Beg Temptation Ain't Too Proud to Beg