34.1966.1 Haynes' Horseless Carriage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horseless Carriage Replica Newsletter

Volume 3 Issue 3 Published by Lee Thevenet May - June, 2011 HORSELESS CARRIAGE REPLICA NEWSLETTER A Publication dedicated to the reporting of news, events, articles, photos, items for sale, etc, having to do with replica horseless carriages. Newsletter published six times a year and special issues when needed. From the Editor Hi everyone, Those of you who were not there, are the one’s that missed out on a great time, making new acquaintances and lots of great buys. Yes, I’m speaking about the Pre War Swap Meet that takes place each March in Chickasha, OK. Like every year before, there was a great time had by all that attended. Lots and lots of vendors showing their goods and beautiful cars to be had for the right price. For myself, this year’s trip to the candy store began a good twenty four hours before the meet was to begin, simply to be there when the vendor’s started to arrive. Remember the old saying “The early bird get’s the worm”. In this case, it was true. My quest this year was to find a very special part that would enable me to complete my REO build that has now gone past the completion time allowed to the project. The plans for the carriage had been completed and put up on the website quite a while back and the actual build, for the most part had been done for almost a year now, except for the final steps of painting and reassembly. Thus, the reason for not having any colored pictures on the REO Plans Page of the HCR.com Website. -

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Sayers, Evelyn M., Ed. Indiana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 288 803 SO 018 629 AUTHOR Sayers, Evelyn M., Ed. TITLE Indiana: A Handbook for U.S. History Teachers. INSTITUTION Indiana State Dept. of Public Instruction, Indianapolis. SPONS AGENCY Indiana Committee for the Humanities, Indianapolis.; National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 228p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; Archaeology; *Citizenship Education; Cultural Education; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Geography Instruction; Instructional Materials; Middle Schools; *Social Studies; State Government; *State History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Indiana; Northwest Territories ABSTRACT This handbook was developed to encourage more effective state citizenship through the teaching of state history. Attention is given to geographical factors, politics, government, social and economic changes, and cultural development. The student is introduced to the study of Indiana history with a discussion of the boundaries, topography, and geologic processes responsible for shaping the topography of the state. The handbook contains 16 chapters, each written by an expert in the field. The chapters are: (1) Indiana Geography; (2) Archaeology and Prehistory; (3) The Indians: Early Residents of Indiana, to 1679; (4) Indiana as Part of the French Colonial Domain, 1679-1765; (5) The Old Northwest under British Control, 1763-1783; (6) Indiana: A Part of the Old Northwest, 1783-1800; (7) The Old Northwest: Survey, Sale and Government; (8) Indiana Territory and Early Statehood, 1800-1825; (9) Indiana: The Nineteenth State, 1820-1877; (10) Indiana Society, 1865-1920; (11) Indiana Lifestyle, 1865-1920; (12) Indiana: 1920-1960; (13) Indiana since 1960; (14) Indiana Today--Manufacturing, Agriculture, and Recreation; (15) Indiana Government; and (16) Indiana: Economic Development Toward the 21st Century. -

A Two-Point Vehicle Classification System

178 TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH RECORD 1215 A Two-Point Vehicle Classification System BERNARD C. McCULLOUGH, JR., SrAMAK A. ARDEKANI, AND LI-REN HUANG The counting and classification of vehicles is an important part hours required, however, the cost of such a count was often of transportation engineering. In the past 20 years many auto high. To offset such costs, many techniques for the automatic mated systems have been developed to accomplish that labor counting, length determination, and classification of vehicles intensive task. Unfortunately, most of those systems are char have been developed within the past decade. One popular acterized by inaccurate detection systems and/or classification method, especially in Europe, is the Automatic Length Indi methods that result in many classification errors, thus limiting cation and Classification Equipment method, known as the accuracy of the system. This report describes the devel "ALICE," which was introduced by D. D. Nash in 1976 (1). opment of a new vehicle classification database and computer This report covers a simpler, more accurate system of vehicle program, originally designed for use in the Two-Point-Time counting and classification and details the development of the Ratio method of vehicle classification, which greatly improves classification software that will enable it to surpass previous the accuracy of automated classification systems. The program utilizes information provided by either vehicle detection sen systems in accuracy. sors or the program user to determine the velocity, number Although many articles on vehicle classification methods of axles, and axle spacings of a passing vehicle. It then matches have appeared in transportation journals within the past dec the axle numbers and spacings with one of thirty-one possible ade, most have dealt solely with new types, or applications, vehicle classifications and prints the vehicle class, speed, and of vehicle detection systems. -

Revisiting the Compcars Dataset for Hierarchical Car Classification

sensors Article Revisiting the CompCars Dataset for Hierarchical Car Classification: New Annotations, Experiments, and Results Marco Buzzelli * and Luca Segantin Department of Informatics Systems and Communication, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126 Milano, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: We address the task of classifying car images at multiple levels of detail, ranging from the top-level car type, down to the specific car make, model, and year. We analyze existing datasets for car classification, and identify the CompCars as an excellent starting point for our task. We show that convolutional neural networks achieve an accuracy above 90% on the finest-level classification task. This high performance, however, is scarcely representative of real-world situations, as it is evaluated on a biased training/test split. In this work, we revisit the CompCars dataset by first defining a new training/test split, which better represents real-world scenarios by setting a more realistic baseline at 61% accuracy on the new test set. We also propagate the existing (but limited) type-level annotation to the entire dataset, and we finally provide a car-tight bounding box for each image, automatically defined through an ad hoc car detector. To evaluate this revisited dataset, we design and implement three different approaches to car classification, two of which exploit the hierarchical nature of car annotations. Our experiments show that higher-level classification in terms of car type positively impacts classification at a finer grain, now reaching 70% accuracy. The achieved performance constitutes a baseline benchmark for future research, and our enriched set of annotations is made available for public download. -

Modelling of Emissions and Energy Use from Biofuel Fuelled Vehicles at Urban Scale

sustainability Article Modelling of Emissions and Energy Use from Biofuel Fuelled Vehicles at Urban Scale Daniela Dias, António Pais Antunes and Oxana Tchepel * CITTA, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Coimbra, Polo II, 3030-788 Coimbra, Portugal; [email protected] (D.D.); [email protected] (A.P.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 March 2019; Accepted: 13 May 2019; Published: 22 May 2019 Abstract: Biofuels have been considered to be sustainable energy source and one of the major alternatives to petroleum-based road transport fuels due to a reduction of greenhouse gases emissions. However, their effects on urban air pollution are not straightforward. The main objective of this work is to estimate the emissions and energy use from bio-fuelled vehicles by using an integrated and flexible modelling approach at the urban scale in order to contribute to the understanding of introducing biofuels as an alternative transport fuel. For this purpose, the new Traffic Emission and Energy Consumption Model (QTraffic) was applied for complex urban road network when considering two biofuels demand scenarios with different blends of bioethanol and biodiesel in comparison to the reference situation over the city of Coimbra (Portugal). The results of this study indicate that the increase of biofuels blends would have a beneficial effect on particulate matter (PM ) emissions reduction for the entire road network ( 3.1% [ 3.8% to 2.1%] by kg). In contrast, 2.5 − − − an overall negative effect on nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions at urban scale is expected, mainly due to the increase in bioethanol uptake. Moreover, the results indicate that, while there is no noticeable variation observed in energy use, fuel consumption is increased by over 2.4% due to the introduction of the selected biofuels blends. -

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG Helen Hu and Richard Green Department of Economics and Institute for Energy Research and Policy University of Birmingham Birmingham B15 2TT United Kingdom Hu: [email protected] Green: [email protected] +44 121 415 8216 (corresponding author) Abstract The adoption of liquefied petroleum gas vehicles is strongly linked to the break-even distance at which they have the same costs as conventional cars, with very limited market penetration at break-even distances above 40,000 km. Hydrogen vehicles are predicted to have costs by 2030 that should give them a break-even distance of less than this critical level. It will be necessary to ensure that there are sufficient refuelling stations for hydrogen to be a convenient choice for drivers. While additional LPG stations have led to increases in vehicle numbers, and increases in vehicles have been followed by greater numbers of refuelling stations, these effects are too small to give self-sustaining growth. Supportive policies for both vehicles and refuelling stations will be required. 1. Introduction While hydrogen offers many advantages as an energy vector within a low-carbon energy system [1, 2, 3], developing markets for hydrogen vehicles is likely to be a challenge. Put bluntly, there is no point in buying a vehicle powered by hydrogen, unless there are sufficient convenient places to re-fuel it. Nor is there any point in providing a hydrogen refuelling station unless there are vehicles that will use the facility. What is the most effective way to get round this “chicken and egg” problem? Data from trials of hydrogen vehicles can provide information on driver behaviour and charging patterns, but extrapolating this to the development of a mass market may be difficult. -

Me Or Body Is Different from the Manufacturer's Specifications, Unless That Difference Is Caused By: A

MAINE Definitions Altered Vehicle. A motor vehicle with a gross vehicle weight rating of 10,000 pounds or less that is modified so that the distance from the ground to the lowermost point on any part of the frame or body is different from the manufacturer's specifications, unless that difference is caused by: A. The use of tires that are no more than 2 sizes larger than the manufacturer's recommended sizes; B. The installation of a heavy duty suspension, including shock absorbers and overload springs; or C. Normal wear of the suspension system that does not affect control of the vehicle. Antique Auto. An automobile or truck manufactured in or after model year 1916 that is: A. More than 25 years old; B. Equipped with an engine manufactured either at the same time as the vehicle or to the specifications of the original engine; C. Substantially maintained in original or restored condition primarily for use in exhibitions, club activities, parades or other functions of public interest; D. Not used as its owner's primary mode of transportation of passengers or goods; E. Not a reconstructed vehicle; and F. Not an altered vehicle. Classic Vehicle. A motor vehicle that is at least 16 years old but less than 26 years old that the Secretary of State determines is of significance to vehicle collectors because of its make, model and condition and is valued at more than $5,000. Custom Vehicle. A motor vehicle manufactured after model year 1948 that: A. Is at least 25 years old or was manufactured to resemble a motor vehicle that is at least 25 years old; and B. -

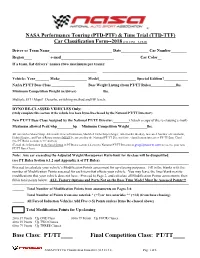

PT & TT Car Classification Form

® NASA Performance Touring (PTD-PTF) & Time Trial (TTD-TTF) Car Classification Form--2018 (v13.1/15.1—1-15-18) Driver or Team Name________________________________ Date______________ Car Number________ Region_____________ e-mail________________________________________ Car Color_______________ If a team, list drivers’ names (two maximum per team): ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Vehicle: Year_______ Make______________ Model___________________ Special Edition?____________ NASA PT/TT Base Class _____________ Base Weight Listing (from PT/TT Rules)______________lbs. Minimum Competition Weight (w/driver)_______________lbs. Multiple ECU Maps? Describe switching method and HP levels:_____________________________________________ DYNO RE-CLASSED VEHICLES Only: (Only complete this section if the vehicle has been Dyno Re-classed by the National PT/TT Director!) New PT/TT Base Class Assigned by the National PT/TT Director:_________(Attach a copy of the re-classing e-mail) Maximum allowed Peak whp_________hp Minimum Competition Weight__________lbs. All cars with a Motor Swap, Aftermarket Forced Induction, Modified Turbo/Supercharger, Aftermarket Head(s), Increased Number of Camshafts, Hybrid Engine, and Ported Rotary motors MUST be assessed by the National PT/TT Director for re-classification into a new PT/TT Base Class! (See PT Rules sections 6.3.C and 6.4) (E-mail the information in the listed format in PT Rules section 6.4.2 to the National PT/TT Director at [email protected] to receive your new PT/TT Base Class) Note: Any car exceeding the Adjusted Weight/Horsepower Ratio limit for its class will be disqualified. (see PT Rules Section 6.1.2 and Appendix A of PT Rules). Proceed to calculate your vehicle’s Modification Points assessment for up-classing purposes. -

Form HSMV 83045

FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF HIGHWAY SAFETY AND MOTOR VEHICLES Application for Registration of a Street Rod, Custom Vehicle, Horseless Carriage or Antique (Permanent) INSTRUCTIONS: COMPLETE APPLICATION AND CHECK APPLICABLE BOX 1 APPLICANT INFORMATION Name of Applicant Applicant’s Email Address Street Address City _ State Zip Telephone Number _ Sex Date of Birth Florida Driver License Number or FEID Number 2 VEHICLE INFORMATION YEAR MAKE BODY TYPE WEIGHT OF VEHICLE COLOR ENGINE OR ID# TITLE# _ PREVIOUS LICENSE PLATE# _ 3 CERTIFICATION (Check Applicable Box) The vehicle described in section 2 is a “Street Rod” which is a modified motor vehicle manufactured prior to 1949. The vehicle meets state equipment and safety requirements that were in effect in this state as a condition of sale in the year listed as the model year on the certificate of title. The vehicle will only be used for exhibition and not for general transportation. A vehicle inspection must be done at a FLHSMV Regional office and the title branded as “Street Rod” prior to the issuance of the Street Rod license plate. The vehicle described in section 2 is a “Custom Vehicle” which is a modified motor vehicle manufactured after 1948 and is 25 years old or older and has been altered from the manufacturer’s original design or has a body constructed from non-original materials. The vehicle meets state equipment and safety requirements that were in effect in this state as a condition of sale in the year listed as the model year on the certificate of title. The vehicle will only be used for exhibition and not for general transportation. -

AZ 85001-2100 96-0143 R02/19 Azdot.Gov • Most Plates May Be Ordered Online At

Arizona Definitions Reconstructed vehicle. A vehicle that has been assembled or constructed largely by means of essential parts, new or used, derived from vehicles or makes of vehicles of various names, models and types or that, if originally otherwise constructed, has been materially altered by the removal of essential parts or by the addition or substitution of essential parts, new or used, derived from other vehicles or makes of vehicles. For the purposes of this paragraph, "essential parts" means integral and body parts, the removal, alteration or substitution of which will tend to conceal the identity or substantially alter the appearance of the vehicle. Historic vehicle. Any of the following: 1. A vehicle bearing a model year date of original manufacture that is twenty-five years old or older. 2. A vehicle included in a list of historic vehicles filed with the director by a recognized historic or classic vehicle organization during the month of December of each year. 3. A reconstructed vehicle that the director determines, on application by the owner, retains at least the basic original body style as manufactured twenty-five years or more before the date of the application. Classic car. A car included in the 1963 list of classic cars filed with the director by the classic car club of America. The director shall revise the list every five years. Horseless carriage. A motor vehicle manufactured in 1915 or before. Specially constructed vehicle. A vehicle not originally constructed under a distinctive name, make, model or type by a generally recognized manufacturer of vehicles. Street Rod. -

Volume 3 Issue 1

Volume 3 Issue 1 Published by Lee Thevenet Jan - Feb, 2011 HORSELESS CARRIAGE REPLICA NEWSLETTER “New Years Issue” A Publication dedicated to the reporting of news, events, articles, photos, items for sale, etc, having to do with replica horseless carriages. Newsletter published six times a year and special issues when needed. From the Editor 2011 2011 Hello Builders, Yes, a very Happy New Year to all of you. Most of us see this time of year as a chance to make needed decisive change’s in our lives. Change’s, which would most likely affect our lives’ for the better. Some make simple changes like cutting back on coffee or sweets, etc. Others tackle more serious challenges like giving up smoking or drinking. Referred to as, New Years Resolutions, these promises to ourselves or family will often fall short of success. Not always because of neglect or unwillingness but simply because we tend to fall back into old routines or habits even if we know better. HCR building can also fall short of success. Other hobbies, distractions and sometimes just lack of funds, can diminish the desire to complete that HCR Project. When making this years resolutions, don’t forget that half completed HCR project…It will bring a lot of happiness & fun times to your life… 1 Toon & Crossword by Lee In This Issue Page Seasons Greetings………………1 Toon & Crossword………………2 Reflections……………………… 3 Terrific HCR Exposure………..4-5 A Very Unique HCR……………6-9 The Pleasure of Winning………10 Picture from Times Past……… 11 Tool Time…………………………11 Economical Buggy Top…… 12-13 Closing Comments………….14-15 OK, OK dear, the next HCR I build will be large enough for both of us to ride! Across 2. -

2015 Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ABOUT THE ALLIANCE This organization focuses on developing economic prosperity for our community by achieving goals and executing programs that benefit Kokomo and Howard County’s residents, businesses, organizations, and visitors. Together, the Alliance’s vision, mission, and values guide our strategic plan and define the ways in which we execute to accomplish the goals within each organizational priority. OUR VISION The vision of the Greater Kokomo Economic Development Alliance seeks to foster economic prosperity for Kokomo and Howard County through new investment, population growth, and the continued success of our area’s current businesses and residents. OUR MISSION The Greater Kokomo Economic Development Alliance aligns, links, and leverages resources to build community prosperity. OUR VALUES We are guided to act and driven to succeed by four sets of values: ∞ Integrity and Respect ∞ Inclusiveness ∞ Efficiency and Effectiveness ∞ Continuous Improvement OUR STRATEGIC PRIORITIES Our goals and actions align with five strategic priorities: ∞ Leadership and Collaboration ∞ Economic Vitality ∞ Talent Attraction ∞ Innovation and Entrepreneurship ∞ Quality Places ANNUAL REPORT: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT KEY ACCOMPLISHMENTS In partnership with local government, the Alliance helped facilitate the attraction of a new primary employer in 2015, Indiana manufacturer Saran Industries, and saw the expansion of local manufacturer METCO, Inc. 2015 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS DESCRIPTION DATE INVESTMENT JOBS ESTIMATE METCO, Inc. 8/2015 $500,000 10 Saran Industries 9/2015 $4.4 million 60 Total 2015 investment $4.9 million 70 ABOUT SARAN INDUSTRIES Headquartered in Indianapolis, Saran Industries provides surface finishing of metal products for the automotive industry. Due to the nature of its operations and close proximity to key clients, Kokomo’s location and skilled workforce made it an ideal location for the company.