Experts in Election News Coverage Process Or Substance?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religion in Danish Newspapers 1750–2018

Continuity with the Past and Uncertainty for the Future: Religion in Danish Newspapers 1750–2018 HENRIK REINTOFT CHRISTENSEN Aarhus University Abstract The article examines the newspaper constructions of religion in Danish newspapers in a quantitative longitudinal analysis from 1750 to 2000 and a more qualitative analysis of recent news production from the last forty years. For the longitudinal part, the database of the digitiza- tion of Danish newspapers project is used. Using the available tools for quantitative data analysis, the article shows that the category of religion and world religions has been visible in Danish newspapers since 1750. The coverage of world religions is often related to the coverage of international news. Overall, the article documents a re- markable continuity of the presence of religion. Examining the more recent material qualitatively, the article shows that although many religions have been historically visible in the news, they have most recently become more frequent in the debate sections than in the news sections. It is primarily Islam that is debated. This is connected with a shift from religious diversity as part of foreign news coverage to domestic news coverage, related to changes in the surrounding Danish society. Nevertheless, the coverage of Islam also displays a remarkable continuity. Keywords: Danish newspapers, coverage of religion, secularization, reli- gious diversity The oriental question is one of today’s most pertinent questions. While some rejoice at the possible fulfilment of the probably quite reasonable wish to see the end of Turkish barbarism in Europe, others hope that this is a con- firmation of Islam’s impotence and the beginning of the eradication and disappearance of Islam from this world. -

Kære Margrethe

4 LEDER Mandagmorgen Kære Margrethe tillykke med dit nye job som leder af Det Radikale Venstre. Det er ingen overraskelse, at det blev dig. Du har den blanding af soberhed, saglighed og alternativ karisma, der kendetegnede din Du forstår bedre end nogen forgænger, og som ofte har været et vinderlod hos De Radikale. Du har en sikker fornemmelse for andre, at dansk politik det politiske spil på Christiansborg. Og når de andre siger, at du hænger dig for meget i forhand- “befinder sig midt i et lingspetitesser, skal du give dem en kold skulder. Djævlen ligger, som man siger, i detaljen, og det spektakulært opbrud. vil også din gamle ven Naser Khader snart finde ud af. Du ved, at det ikke altid er nemt at være dygtig og flittig. Når dine studiekammerater gik ud for at male byen rød, sad du til møde som for- mand for Det Radikale Venstre. Ingen skal sige, at du er kommet sovende til tops. Du ved, at hel- det følger den arbejdsomme. Derfor er du også i den gunstige situation, at det kan blive netop dig, der får mest ud af det opbrud, som er sat i gang i dansk politik. Med din strategiske tæft kan du pla- cere Det Radikale Venstre netop der, hvor Ny Alliance og Naser Khader så gerne vil være: på den politiske midte. Når du læser disse helt private linjer, har du haft tid til at studere weekendens aviser og fordøje det politiske ulvekobbels mere eller mindre indsigtsfulde analyser. Siderne har været plastret til med superlativer – ikke kun om dig, men også om din gamle ven og mentor, Marianne. -

Betænkning Over Forslag Til Lov Om Ændring Af Værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for Værnepligtstjeneste for Visse Personer, Der Er Blevet Udskrevet Til Tjeneste Før 2010)

Udskriftsdato: 27. september 2021 2018/1 BTL 4 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for værnepligtstjeneste for visse personer, der er blevet udskrevet til tjeneste før 2010) Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Forsvarsudvalget den 22. november 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for værnepligtstjeneste for visse personer, der er blevet udskrevet til tjeneste før 2010) [af forsvarsministeren (Claus Hjort Frederiksen)] 1. Indstilling Udvalget indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. Nunatta Qitornai, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin havde ved betænkningsafgivelsen ikke medlemmer i udvalget og dermed ikke adgang til at komme med indstillinger eller politiske bemærkninger i betænknin- gen. En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt i betænkningen. 2. Politiske bemærkninger Enhedslisten og Inuit Ataqatigiit Enhedslistens og Inuit Ataqatigiits medlemmer af udvalget bemærker, at der er en principiel udfordring i, at regeringen fremsætter ændringslovforslag til en lov, der gælder i hele rigsfællesskabet. Det fremgår i høringsoversigten, at regeringen har til hensigt at udarbejde en kongelig anordning for Grønland og Færøerne senere. Når dette sker, vil Inatsisartut komme med en udtalelse, jf. selvstyreloven, men det er uskøn proces, når der er tale om en lov, der omhandler hele rigsfællesskabet, som ændres i forskellige tempi, afhængigt af hvor i rigsfællesskabet man som borger befinder sig. 3. Udvalgsarbejdet Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 3. oktober 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 11. oktober 2018. Lovfor- slaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Forsvarsudvalget. Oversigt over lovforslagets sagsforløb og dokumenter Lovforslaget og dokumenterne i forbindelse med udvalgsbehandlingen kan læses under lovforslaget på Folketingets hjemmeside www.ft.dk. -

Økonomisk-Politisk Kalender

Microsoft Word − 121−124 Kalender.doc (X:100.0%, Y:100.0%) Created by Grafikhuset Publi PDF. Økonomisk-politisk kalender Økonomisk-politisk kalender 7. apr. Nyt ministerhold Statsminister Lars Løkke Rasmussen (V) har sat sit nye mi- Den økonomisk-politiske kalender for perioden primo nisterhold. Ændringer i forhold til regeringen Fogh Rasmus- 2009 og frem indeholder en summarisk oversigt over sen: vigtige økonomisk-politiske indgreb og begivenheder, • Beskæftigelsesminister Claus Hjort Frederiksen (V) der kan have betydning for vurderingen af tidsserierne i bliver ny finansminister og erstatter dermed Lars Konjunkturstatistik . Løkke Rasmussen • Inger Støjberg (V) bliver ny beskæftigelses- og lige- stillingsminister 2009 • Karen Ellemann (V) bliver indenrigs- og social- minister. 27. feb. Bruttonationalproduktet dykker Det danske BNP faldt 2 pct. i fjerde kvartal 2008, når der er Karen Jespersen fratræder samtidig som velfærdsminister og korrigeret for sæsonudsving. Det er primært de private inve- minister for ligestilling. Hendes områder fordeles på Inger steringer, der nærmest er gået i stå, og der er store fald i Støjberg og Karen Ellemann. Velfærdsministeriet skifter både import og eksport. Udviklingen er den samme i det navn til Indenrigs- og socialministeriet. øvrige EU og USA i fjerde kvartal, hvor finanskrisen for alvor er slået igennem. 14. april Nu muligt at søge penge fra renoveringspuljen Regeringens renoveringspulje, som udgør 1,5 mia. kr., tager 6. marts Rentenedsættelse til 2,25 pct. imod ansøgninger fra boligejere eller lejere, der vil have Nationalbankens udlånsrente nedsættes med 0,75 procent- lavet forbedringer på deres hus. Tilskuddet kan maksimalt point til 2,25 pct. være 40 pct. af arbejdslønnen inklusiv moms - dog højst 15.000 kr. -

Betænkning Over Forslag Til Folketingsbeslutning Om Større Statslig Medfinansiering Af Kunstakademierne I Aarhus Og Odense

Udskriftsdato: 1. oktober 2021 2017/1 BTB 70 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om større statslig medfinansiering af kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Kulturudvalget den 9. maj 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om større statslig medfinansiering af kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense [af Alex Ahrendtsen (DF) m.fl.] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 1. februar 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 2. marts 2018. Be slutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Kulturudvalget. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (udvalget med undtagelse af DF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Enhedslistens medlemmer af udvalget kan ikke støtte forslaget. Ved førstebehandlingen af forslaget efterlyste Enhedslisten nogle begrundelser for forslaget – ud over ønsket om at overføre penge fra kunstakademiet i København til kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense. Samtidig efterlyste Enhedslisten forslagsstillernes analyse af, hvad konsekvenserne af forslaget ville blive for den samlede kunstakade miuddannelse i Danmark. Desværre fremlagde forslagsstillerne hverken disse begrundelser/analyser under førstebehandlingen eller i forbindelse med udvalgsbehandlingen. Et mindretal i udvalget (DF) indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse. Inuit Ataqatigiit, Nunatta Qitornai, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin var på tidspunktet for betænknin -

Betænkning Forslag Til Folketingsbeslutning Om Opfordring

Skatteudvalget 2010-11 B 144 Bilag 8 Offentligt Til beslutningsforslag nr. B 144 Folketinget 2010-11 Betænkning afgivet af Skatteudvalget den 27. juni 2011 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om opfordring til at trække aktstykke 128 af 12. maj 2011 om permanent toldkontrol i Danmark (styrket grænsekontrol) tilbage fra Finansudvalget med henblik på at styrke forudsætningerne for en mobil, fleksibel og efterretningsbaseret indsats mod grænseoverskridende kriminalitet [af Morten Bødskov (S), Ole Sohn (SF), Morten Østergaard (RV) og Christian H. Hansen (UFG) m.fl.] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Dansk Folkepartis aktstykke nr. 128 af 12. maj 2011 om Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 14. juni 2011 og permanent toldkontrol i Danmark indeholder et krav om per- var til 1. behandling den 21. juni 2011. Beslutningsforslaget manente grænseanlæg, hvilket er til skade for dansk er- blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Skatteudval- hvervsliv, da det hæmmer den fri bevægelighed mellem de get. europæiske lande. Det skader Danmarks handelsmuligheder og gør det vanskeligere at tiltrække udenlandske virksomhe- Møder der og arbejdskraft. Samtidig stopper de permanente græn- Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 3 møder. seanlæg ikke de kriminelle udlændinge. LA mener, at vi kun kommer grænseoverskridende kriminalitet til livs med en Samråd større efterretningsbaseret indsats og flere, og ikke færre, Udvalget har stillet 3 spørgsmål til skatteministeren og 2 patruljerende betjente. spørgsmål til justitsministeren til mundtlig besvarelse, -

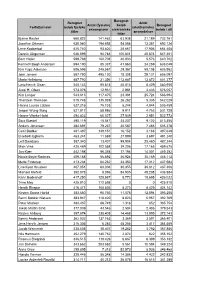

Se Samlet Liste Over Modtagere I 2020

Beregnet Beregnet Antal Antal (fysiske) beløb Beregnet Forfatternavn beløb fysiske (elektroniske) eksemplarer elekroniske beløb i alt titler anvendelser titler Bjarne Reuter 668.822 141.462 63.938 21.189 732.761 Josefine Ottesen 638.040 194.693 54.084 13.381 692.124 Lene Kaaberbøl 625.740 93.802 28.667 17.906 654.408 Dennis Jürgensen 546.599 94.784 100.801 20.674 647.401 Bent Haller 599.769 160.708 40.933 5.576 640.702 Kenneth Bøgh Andersen 594.190 85.337 41.860 24.259 636.049 Kim Fupz Aakeson 606.596 246.567 29.367 58.108 635.962 Jørn Jensen 587.790 495.130 18.308 29.131 606.097 Maria Helleberg 487.790 31.356 113.487 13.872 601.277 Lars-Henrik Olsen 540.143 95.818 40.813 8.429 580.956 Jussi H. Olsen 573.076 12.931 2.981 3.433 576.057 Kim Langer 543.613 117.475 23.381 25.724 566.994 Thorstein Thomsen 515.748 135.939 26.282 5.335 542.029 Hanna Louisa Lützen 527.216 75.133 8.244 4.844 535.459 Jesper Wung-Sung 521.817 58.986 9.911 4.753 531.728 Hanne-Vibeke Holst 494.823 60.027 27.949 2.951 522.773 Sara Blædel 490.119 15.047 23.237 9.122 513.356 Anders Johansen 484.691 79.237 20.587 7.465 505.278 Cecil Bødker 481.497 139.151 16.152 3.188 497.649 Elsebeth Egholm 463.241 11.869 27.999 3.697 491.240 Leif Davidsen 387.340 13.407 99.904 20.460 487.244 Mich Vraa 420.469 102.558 39.206 17.165 459.675 Jan Kjær 442.198 96.358 17.194 14.001 459.392 Nicole Boyle Rødtnes 409.188 56.692 36.924 35.169 446.112 Mette Finderup 413.234 64.262 24.350 17.312 437.584 Line Kyed Knudsen 407.051 68.304 30.355 36.812 437.406 Michael Krefeld 352.078 8.096 84.905 -

Preventing Extremism and Radicalization, In- Whereas Today the Frontline Staff Ask for Assistance.51 Cluding a Focus on Preventing the More Social Aspects

Retsudvalget 2015-16 REU Alm.del Bilag 248 Offentligt DIIS REPORT 2015: 15 An Introduction to THE DANISH APPROACH TO COUNTERING AND PREVENTING EXTREMISM AND RADICALIZATION THE DANISH APPROACH TO COUNTERING AND PREVENTING EXTREMISM AND RADICALISATION Contents Abstract 5 Introduction 6 Background 10 Structural arrangements and ideological foundations 14 Main elements and actors 22 The General level 24 The specific level 26 The Targeted level 27 Info-houses bringing together police and municipalities 27 The Centre for Prevention of the Danish Security and Intelligence Service 29 The Ministry of Immigration, Integration and Housing, and the Danish Agency for International Recruitment and Integration 30 The Danish Prison and Probation Service 30 Municipalities 31 Cooperation networks 33 Expansion 33 Dilemmas, challenges and criticisms 34 This report is written by Ann-Sophie Hemmingsen and published by DIIS. Fundamental criticism 36 Ann-Sophie Hemmingsen, Ph.D., is a researcher at DIIS. Political criticism 38 The risk of creating self-fulfilling prophecies 39 DIIS · Danish Institute for International Studies Lack of consensus, clear definitions and evaluations 40 Østbanegade 117, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Practical challenges 42 Tel: +45 32 69 87 87 Civil society 44 E-mail: [email protected] www.diis.dk Notes 47 Literature 50 Layout: Mark Gry Christiansen Printed in Denmark by Eurographic Danmark ISBN 978-87-7605-771-8 (print) ISBN 978-87-7605-770-1 (pdf) All DIIS publications are available for free on DIIS.DK ©Copenhagen 2015, the author and DIIS THE DANISH APPROACH TO COUNTERING AND PREVENTING EXTREMISM AND RADICALISATION 3 ABSTRACT Preventing and countering violent extremism and radicalization is increasingly gain- ing momentum as a supplement to more traditional counterterrorism activities in the efforts to protect societies against terrorism. -

Reading the Surface: the Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C

Reading the Surface: The Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C. Andersen, Karen Blixen and Beyond Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: Marianne Stecher. Chair Jan Sjaavik Marshall Brown Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Scandinavian Studies ©Copyright 2013 Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg Parts of chapter 7 are reprinted by permission of the publishers from “The Aesthetics of Surface: the Danish Gothic 1820-2000,” in Gothic Topographies ed. P.M. Mehtonen and Matti Savolainen (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), pp. 153–167. Copyright © 2013 University of Washington Abstract Reading the Surface: The Danish Gothic of B.S. Ingemann, H.C. Andersen, Karen Blixen and Beyond Kirstine Marie Kastbjerg Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor in Danish Studies Marianne Stecher Department of Scandinavian Studies Despite growing ubiquitous in both the popular and academic mind in recent years, the Gothic has, perhaps not surprisingly, yet to be examined within the notoriously realism-prone literary canon of Denmark. This dissertation fills that void by demonstrating an ongoing negotiation of Gothic conventions in select works by canonical Danish writers such as B.S. Ingemann, Hans Christian Andersen, and Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen), as well as contemporary writers such as Peter Høeg and Leonora Christina Skov. This examination does not only broaden our understanding of these culturally significant writers and the discourses they write within and against, it also adds to our understanding of the Gothic – an infamously malleable and indefinable literary mode – by redirecting attention to a central feature of the Gothic that has not received much critical attention: the emphasis on excess, spectacle, clichéd conventions, histrionic performances, its hyperbolic rhetorical style, and hyper-visual theatricality. -

Survival of the Richest. Europe's Role in Supporting an Unjust Global Tax

Survival of the Richest Europe’s role in supporting an unjust global tax system 2016 Acknowledgements This report was produced by civil society organisations in countries across Europe, including: Attac Austria (Austria); Vienna Institute for International Dialogue and Cooperation (VIDC) (Austria); 11.11.11 (Belgium); Centre national de coopération au développement (CNCD-11.11.11) (Belgium); Glopolis (Czech Republic); Oxfam IBIS (Denmark); Kehitysyhteistyön palvelukeskus (KEPA) (Finland); CCFD-Terre Solidaire (France); Oxfam France (France); Netzwerk Steuergerechtigkeit (Germany); Debt and Development Coalition Ireland (DDCI) (Ireland); Oxfam Italy (Italy); Re:Common (Italy); Latvijas platforma attīstības sadarbībai (Lapas) (Latvia); Collectif Tax Justice Lëtzebuerg (Luxembourg); the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) (Netherlands); Tax Justice Netherlands (Netherlands); Tax Justice Network Norway (Norway); Instytut Globalnej Odpowiedzialnosci (IGO) (Poland); Ekvilib Institute (Slovenia); Focus Association for Sustainable Development (Slovenia); Inspiraction (Spain); Forum Syd (Sweden); Christian Aid (UK). The overall report was coordinated by Eurodad. Each national chapter was written by – and is the responsibility of – the nationally-based partners in the project. The views in each chapter do not reflect the views of the rest of the project partners. The chapters on Luxembourg and Spain were written by – and are the responsibility of – Eurodad. Design and artwork: James Adams. Copy editing: Vicky Anning, Jill McArdle and Julia Ravenscroft. The authors believe that all of the details of this report are factually accurate as of 15 November 2016. This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and Open Society Foundations. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Eurodad and the authors of the report, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the funders. -

Distribution and Use of Image-Evoking Language Constructions in Written News

10.1515/nor-2017-0212 Nordicom Review 28 (2007) 2, pp. 93-109 Distribution and Use of Image-evoking Language Constructions in Written News EBBE GRUNWALD & JØRGEN LAURIDSEN Abstract Linguistic exposures are image constructions and some of the most distinctive mechanisms in the discourse community of journalism. By exposing the journalistic writers add focus, detail and substantiation to their sto- ries. Linguistic exposures are tools that evoke images in the readers’ minds and help es- tablish and improve the basis of interest and understanding. We are combining linguistic and statistical methods to investigate exposures in the news of five Danish national papers in order to determine how widespread it is, and with what force and impact the techniques are used. Our study contributes to existing knowledge by focusing on form rather than content. We investigate the creative use of specific structural elements of the language as the prevailing contact establishing tools of journalistic discourse. Our data are based on news from Berlingske Tidende, B.T., Politiken, Ekstra Bladet and Morgenavisen Jyllands-Posten. Key Words: journalism, newspapers, written news, narrative tools, image constructions, metaphor Introduction Within recent years, several Danish and European newspaper companies have developed into media houses that integrate technologies and strategies that were formerly thought of as separate within journalism and communication.1 Furthermore, journalists are now being educated to act within cross-media environments and to handle newspaper jour- nalism on the same professional level as radio, television and especially web journal- ism. Multimedia competences are consequently going to be an integrated qualification among many modern journalists. -

Folketingets Ombudsmands Pension, Ombudsmandens Kompetence I Forhold Til Halvoffentlige Organer Og Private Institutioner M.V.)

Udskriftsdato: 2. oktober 2021 2008/1 TBL 213 (Gældende) Tillægsbetænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om Folketingets Ombudsmand (Folketingets ombudsmands pension, Ombudsmandens kompetence i forhold til halvoffentlige organer og private institutioner m.v.) Ministerium: Folketinget Tillægsbetænkning afgivet af Retsudvalget den 27. maj 2009 Tillægsbetænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om Folketingets Ombudsmand (Folketingets ombudsmands pension, Ombudsmandens kompetence i forhold til halvoffentlige organer og private institutioner m.v.) [af Thor Pedersen (V), Svend Auken (S), Søren Espersen (DF), Holger K. Nielsen (SF) og Helge Adam Møller (KF)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 7. maj 2009 og var til 1. behandling den 13. maj 2009. Lovforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Retsudvalget. Udvalget afgav betænkning den 19. maj 2009. Lovforslaget var til 2. behandling den 26. maj 2009, hvorefter det blev henvist til fornyet behandling i Retsudvalget. Møder Udvalget har, efter at lovforslaget blev henvist til fornyet udvalgsbehandling, behandlet dette i 1 møde. Spørgsmål Et af udvalgets spørgsmål til Folketingets formand og dennes svar herpå er optrykt som bilag 2 til tillægsbetænkningen. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Udvalget indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. Dansk Folkeparti konstaterer, at lovforslaget indeholder en række ændringer vedrørende ombuds- mandsinstitutionen. Dansk Folkeparti kan generelt acceptere disse ændringer, hvorfor Dansk Folkeparti også via sit præsidiemedlem har været med til at fremsætte lovforslaget. Kun et forhold er grundlæggende forkert i forslaget. Nemlig at ombudsmanden med tilbagevirkende kraft skal have forøget sin pension med knap 130.000 kr. årligt. I dag har ombudsmanden ret til en pension på ca. 350.000 kr., hvorfor der med tilbagevirkende kraft sker en voldsom forøgelse.