BUSCH-DISSERTATION-2012.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published Bi-Monthly by the State Historical Society of Colorado

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published bi-monthly by The State Historical Society of Colorado Vol.XVIII Denver, Colorado, September, 1941 No. 5 John Taylor-Slave-Born Colorado Pioneer* D. B. McGuE "Yes, sub-yes, sub, I wuz de fust white man to settle in de Pine ribber valley ob sou 'wes 'rn Colorado.'' ''That's right, John,'' chorused a group of a dozen or more grizzled white men, gathered at an annual reunion of San Juan pioneers-those argonauts who came to the region before 1880. My eyes bugged out like biscuits. The first speaker was a black man. A short, chunky block of glistening granite black. John Taylor. One of the most interesting characters ever to ride the wild trails in the wild southwest and across the border into Mexico before he settled in southwestern Colorado . .John Taylor was born at Paris, Kentucky, in 1841, according to his army record. He was the son of slave parents. ''Cos I doan 't 'membah much about de fust, two, free yea 's ob my life,'' John declared. ''But I 'spect I wuz lak all de odah pickaninnies. I suah does 'membah clat as soon as I wuz big 'nuf to mock a man at wo'k, I wuz sent into de cawn an' baccy fiel's, an' 'til I wuz twenty-free I wuz raised on de hamlle ob a hoe." ''And then what happened, John?'' ''I becomes a runaway niggah, '' John chuckled. On August 17, 1864, John Taylor enlisted in the first negro regiment recruited by Union army officials in Kentucky. -

Thesis Rapid Ascent: Rocky Mountain National Park In

THESIS RAPID ASCENT: ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK IN THE GREAT ACCELERATION, 1945-PRESENT Submitted by Mark Boxell Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2016 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mark Fiege Ben Bobowski Adrian Howkins John Lindenbaum Jared Orsi Copyright by Mark Boxell 2016 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT RAPID ASCENT: ROCKY MOUNTAIN NATIONAL PARK IN THE GREAT ACCELERATION, 1945-PRESENT After the Second World War’s conclusion, Rocky Mountain National Park (RMNP) experienced a massive rise in visitation. Mobilized by an affluent economy and a growing, auto- centric infrastructure, Americans rushed to RMNP in droves, setting off new concerns over the need for infrastructure improvements in the park. National parks across the country experienced similar explosions in visitation, inspiring utilities- and road-building campaigns throughout the park units administered by the National Park Service. The quasi-urbanization of parks like RMNP implicated the United States’ public lands in a process of global change, whereby wartime technologies, cheap fossil fuels, and a culture of techno-optimism—epitomized by the Mission 66 development program—helped foster a “Great Acceleration” of human alterations of Earth’s natural systems. This transformation culminated in worldwide turns toward mass-urbanization, industrial agriculture, and globalized markets. The Great Acceleration, part of the Anthropocene— a new geologic epoch we have likely entered, which proposes that humans have become a force of geologic change—is used as a conceptual tool for understanding the connections between local and global changes which shaped the park after World War II. -

Aauw Fall2015 Bulletin Final For

AAUWCOLORADObulletin fall 2015 Fall Leadership Conference-- Focusing On the Strategic Plan Our Fall Leadership Conference will be held August 28-29 at Lion Square Lodge in Vail, Colorado. Lion Square Lodge is located in the Lionshead area of Vail. The group rates are available for up to 2 days prior and 2 days after our conference subject to availability. The Fall Conference is a time for state and branch offi cers to meet and work together. The conference is open to any member, but branches should be sure to have their offi cers attend and participate. This is your opportunity to help us as we work toward the achieve- ment of the state strategic plan. This year’s conference will focus on areas identifi ed in the strategic plan. We have also utilized input received from Branch Presidents on a survey conducted this spring where the greatest need identifi ed was Mission Based Pro- gramming. We will be incorporating the topic of Mission Based Programing during the conference. Branch Program and Branch Membership Chairs should also attend to gain this important information. There will be a time for Branch Presidents/Administrators who arrive on Friday afternoon to meet together. This will be an opportunity to get acquainted with your peers and share successes and provide input to the state offi cers on what support you need. The state board will also be meeting on Saturday. Lion Square Lodge Lounge Area The tentative schedule, hotel information and registration are on pages 2-3 of this Bulletin. IN THIS ISSUE: FALL LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE...1-3, PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE...4, PUBLIC POLICY...4 LEGISLATIVE WRAPUP...5-6, WOMEN’S HALL OF FAME BOOKLIST...7-8 WOMEN POWERING CHANGE...9, BRANCHES...10 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS...11, MCCLURE GRANT APPLICATION...12 AAUW Colorado 2015 Leadership Conference Lions Square Lodge, Vail, CO All meetings will be held in the Gore Creek & Columbine Rooms (Tentative Schedule) Friday, August 28 2:00 – 3:30 p.m. -

Augusta Tabor

AUGUSTA TABOR When: 1833-1895 Where: Born in Maine, moved to Kansas, and then to Colorado Why Important: Augusta successfully ran businesses, owned real estate, and carefully managed her money at a time when few women were allowed to be involved in financial and business matters. Augusta Tabor. Studio portrait of (probably) Augusta Louise Tabor, in a dress with lace and a straw hat. Between 1840 and 1850? Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. Call Number: X-21988. Augusta’s Leadville house. View of the Horace and Augusta Tabor home, at 116 East 5th (Fifth) Street, in Leadville, (Lake County), Colorado; shows a frame house with a bay window and bargeboard. 1955. Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. Call Number: X-21996. Mrs. H. A. W. Tabor. A.E. Rinehart, Denver, Colo. Studio portrait of Augusta Louise Tabor, wearing a lace shawl, earrings, and ringlets. Between 1880 and 1890? Denver Public Library, Western History Collection. Call Number: X-21992. AUGUSTA TABOR Augusta Louise Pierce was born March 29, 1833 in Maine. She met Horace Tabor, a stone-cutter her father hired to work in his quarry. They got married on January 31, 1857. The couple moved to a small town in Kansas and worked as farmers. In 1859, Horace, Augusta, and their son, Maxey, moved to Colorado. Horace hoped to make money mining for gold. Augusta earned money cooking and doing laundry for the miners. They moved again to Oro City and started a grocery store where Augusta worked. Horace was doing well mining. However, Horace wanted to make more money and moved the family to Leadville. -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

'Baby' Tabor - 'The Ballad of Baby Doe' - Includes Related Information

This cloud had a silver lining: the Washington Opera has revived the improbable story of Horace and 'Baby' Tabor - 'The Ballad of Baby Doe' - includes related information Insight on the News, Feb 10, 1997 by T.L. Ponick No matter how hard he tried, luck always seemed to elude Horace Tabor, the central figure in a celebrated mining-town rags-to-riches saga. From before the Civil War to the boom times of the 1870s, Tabor prospected for gold and silver in the craggy mountains of Western Colorado without much to show for it. When, suddenly, he hit pay dirt, he became the biggest man in Leadville and one of the richest in Colorado. Tabor built an opera house, cast off his dour-looking wife, hitched himself to a colorful woman of dubious virtue named "Baby" Doe and spent money as of he owned the Denver mint -- only to die penniless at century's end, a victim of the nation's abandonment of freely coined silver, leaving his flamboyant wife in rags. Authentic legends of the West, Horace and Baby Doe Tabor and their times were brought to the stage in July 1956 by composer Douglas Moore and librettist John Latouche for the Central City Opera of Denver. The Ballad of Baby Doe was revised for its New York City Opera premiere in 1958, with Beverly Sirs starring in the difficult coloratura role of Baby. In January, the Washington Opera unveiled its production featuring soprano Elisabeth Comeaux and baritone Richard Stilwell, a Metropolitan Opera veteran, as the Tabors, with mezzo Phyllis Pancella as the spurned wife Augusta. -

Mining Wars: Corporate Expansion and Labor Violence in the Western Desert, 1876-1920

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 2009 Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920 Kenneth Dale Underwood University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Underwood, Kenneth Dale, "Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 106. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1377091 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINING WARS: CORPORATE EXPANSION AND LABOR VIOLENCE IN THE WESTERN DESERT, 1876-1920 by Kenneth Dale Underwood Bachelor of Arts University of Southern California 1992 Master -

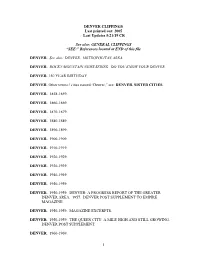

Denver Public Library Clipping Files

DENVER CLIPPINGS Last printed out: 2005 Last Updates 5/21/19 CR See also: GENERAL CLIPPINGS “SEE:” References located at END of this file DENVER. See also: DENVER. METROPOLITAN AREA. DENVER. ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS SERIES. DO YOU KNOW YOUR DENVER. DENVER. 150 YEAR BIRTHDAY DENVER. Other towns / cities named “Denver,” see: DENVER. SISTER CITIES. DENVER. 1858-1859. DENVER. 1860-1869. DENVER. 1870-1879. DENVER. 1880-1889. DENVER. 1890-1899. DENVER. 1900-1909. DENVER. 1910-1919. DENVER. 1920-1929. DENVER. 1930-1939. DENVER. 1940-1949. DENVER. 1950-1959. DENVER. 1950-1959. DENVER: A PROGRESS REPORT OF THE GREATER DENVER AREA. 1957. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT TO EMPIRE MAGAZINE. DENVER. 1950-1959. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1950-1959. THE QUEEN CITY: A MILE HIGH AND STILL GROWING. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT. DENVER. 1960-1969. 1 DENVER. 1960-1969. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1960-1969. TEN STEPS TO GREATNESS. SERIES. 1964. DENVER. 1970-1979. DENVER. 1970-1979. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1970-1979. THE WHOLE CONSUMER GUIDE: A DENVER AREA GUIDE TO CONSUMER AND HUMAN RESOURCES. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT. NOVEMBER 5, 1978. DENVER. 1980-1989. DENVER. 1980-1989. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1990-1999. DENVER. 2000-2009. DENVER. 2003. THE MILE HIGH CITY. DENVER. DENVER. 2008. 2008 OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE. DENVER. A SHORT HISTORY OF DENVER. 1 OF 2. DENVER. A SHORT HISTORY OF DENVER. 2 OF 2. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1860-1899. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1890-1899. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1900-1909. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1910-1919. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1920-1929. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1930-1939. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1940-1949. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1950-1959. DENVER. -

Public Danger

DAWSON.36.6.4 (Do Not Delete) 8/19/2015 9:43 AM PUBLIC DANGER James Dawson† This Article provides the first account of the term “public danger,” which appears in the Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Drawing on historical records from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Article argues that the proper reading of “public danger” is a broad one. On this theory, “public danger” includes not just impending enemy invasions, but also a host of less serious threats (such as plagues, financial panics, jailbreaks, and natural disasters). This broad reading is supported by constitutional history. In 1789, the first Congress rejected a proposal that would have replaced the phrase “public danger” in the proposed text of the Fifth Amendment with the narrower term “foreign invasion.” The logical inference is that Congress preferred a broad exception to the Fifth Amendment that would subject militiamen to military jurisdiction when they were called out to perform nonmilitary tasks such as quelling riots or restoring order in the wake of a natural disaster—both of which were “public dangers” commonly handled by the militia in the early days of the Republic. Several other tools of interpretation—such as an intratextual analysis of the Constitution and an appeal to uses of the “public danger” concept outside the Fifth Amendment—also counsel in favor of an expansive understanding of “public danger.” The Article then unpacks the practical implications of this reading. First, the fact that the Constitution expressly contemplates “public danger” as a gray area between war and peace is itself an important and unexplored insight. -

Merola Opera Program: Schwabacher Summer Concert

Merola Opera Program Schwabacher Summer Concert 2017 WHEN: VENUE Sunday, Bing JuLy 9, 2017 ConCert HaLL 2:30 PM Photo: Kristen Loken Program (Each excerpt’s cast listed by order of appearance) Jules Massenet: Thaïs (1894) Giacomo Puccini: Le Villi (1884) from act 2 “La tregenda” “Ah, je suis seule…Dis-moi que je suis belle…Étranger, te voilà.” orchestra thaïs—Mathilda edge Douglas Moore: The Ballad of Baby Doe (1956) athanaël—thomas glass act 1, Scenes 2 and 3 nicias—andres acosta “What a lovely evening…Willow where we met together… Warm as the autumn light…Now where do you suppose that Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria rusticana (1890) he can be?...I send these lacy nothings.” “Tu qui, Santuzza…Fior di giaggiolo… Ah, lo vedi, che hai tu detto.” Baby doe—Kendra Berentsen Horace tabor—dimitri Katotakis turiddu—Xingwa Hao augusta tabor—alice Chung Santuzza—alice Chung Kate—Mathilda edge Lola—alexandra razskazoff Meg—Felicia Moore Samantha—alexandra razskazoff Kurt Weill: Street Scene (1947) townspeople—Mathilda edge, act 1, Scene 7 (“ice Cream Sextet”) Felicia Moore, alexandra razskazoff, andres acosta, “First time I come to da America…” thomas glass Lippo—andres acosta Gaetano Donizetti: Lucrezia Borgia (1833) Mrs. Jones—alexandra razskazoff from act 1 Mrs. Fiorentino—Kendra Berentsen “Tranquillo ei posa…Com’è bello…Ciel! Che vegg’io?...Di Mrs. olsen—alice Chung pescatore ignobile.” Henry—Xingwa Hao Mr. Jones—thomas glass Lucrezia—alexandra razskazoff Mr. olsen—dimitri Katotakis gubetta—thomas glass duke—dimitri Katotakis rustighello—Xingwa Hao anne Manson, conductor gennaro—andres acosta david Lefkowich, director Carl Maria von Weber: Der Freischütz (1821) from act 2 “Wie nahte mir der Schlummer…Leise, leise, fromme Weise… Wie? Was? Entsetzen!” agathe—Felicia Moore Max—Xingwa Hao Ännchen—Kendra Berentsen INTERMISSION PROGRAM SUBJECT TO CHANGE. -

Labor History Timeline

Timeline of Labor History With thanks to The University of Hawaii’s Center for Labor Education and Research for their labor history timeline. v1 – 09/2011 1648 Shoemakers and coopers (barrel-makers) guilds organized in Boston. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu. Image:http://mattocks3.wordpress.com/category/mattocks/james-mattocks-mattocks-2/ Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1776 Declaration of Independence signed in Carpenter's Hall. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image:blog.pactecinc.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1790 First textile mill, built in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was staffed entirely by children under the age of 12. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu Image: creepychusetts.blogspot.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1845 The Female Labor Reform Association was created in Lowell, Massachusetts by Sarah Bagley, and other women cotton mill workers, to reduce the work day from 12-13 hours to10 hours, and to improve sanitation and safety in the mills. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: historymartinez.wordpress.com Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1868 The first 8-hour workday for federal workers took effect. Text: http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu/Timeline-US.html, Image: From Melbourne, Australia campaign but found at ntui.org.in Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1881 In Atlanta, Georgia, 3,000 Black women laundry workers staged one of the largest and most effective strikes in the history of the south. Sources: Text:http://clear.uhwo.hawaii.edu, Image:http://www.apwu.org/laborhistory/10-1_atlantawomen/10-1_atlantawomen.htm Labor History Timeline – Western States Center 1886 • March - 200,000 workers went on strike against the Union Pacific and Missouri Pacific railroads owned by Jay Gould, one of the more flamboyant of the 'robber baron' industrialists of the day. -

This Is 2007. Increased, but in 1971 We Realized That Our Name to Reflect Our Growth

year: 1 year: 28 year: 46 This is our 64th year of social responsibility. On Feb. 27, 1943, the doors of Belle Bonfils Memorial Blood Bank opened and history Growth for Bonfils over the past Therefore, we became Belle Bonfils Bonfils received approval to administer a another year was made. Dr. Osgood Philpott and philanthropist Helen G. Bonfils helped to 28 years occurred both physically Memorial Blood Center. Bonfils was no local office of the National Marrow Donor realize the Rocky Mountain Region’s need for blood services and led the founding of and philosophically. Not only did longer just a blood bank; our services Program in 1989, allowing us to help This is our 64th year of customer satisfaction. of successes Denver’s first community blood bank. However, Bonfils was not born of need alone, we repeatedly outgrow offices and were expanding, especially in the area of recruit and maintain records of persons 2007 but with a vision to aid the local community as well as the military forces fighting laboratories as our community support transfusion medicine and it was time for willing to donate bone marrow. This was overseas in World War II. This vision would carry on and reach across the state—across a monumental step for Bonfils and before This is 2007. increased, but in 1971 we realized that our name to reflect our growth. And the year: To Our Community: decades—to become an intricate and integral part of Colorado’s healthcare system. the name Belle Bonfils Memorial growing didn’t stop there. long, the results started to show.