Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary, Vicksburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 8, No. 3, Fall 2013 Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Cornerstone Newsletters Fall 2013 Vol. 8, no. 3, Fall 2013 Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/morrisnews_cornerstone Recommended Citation Southern Illinois University Carbondale, "Vol. 8, no. 3, Fall 2013" (2013). Cornerstone. Paper 30. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/morrisnews_cornerstone/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Newsletters at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornerstone by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 8, Number 3 Fall 2013 The Newsletter of Morris Library • Southern Illinois University Carbondale Vicksburg @ 150 By Aaron Lisec fter a series of battles and a 47-day siege the strategic river Aport of Vicksburg, Mississippi, surrendered to Union troops on July 4, 1863. With this strategic victory the Union controlled the Mississippi River and cut the Confederacy in two from east to west. This Spring the Special Collections Research Center commemorated this milestone with Vicksburg @ The Illinois Memorial In This Issue 150, an exhibit of photographs as the father of the • Library is Seeking and firsthand skyscraper. Dedicated Page 3 & 6 accounts in in 1906, the largest the Hall of state monument at Presidents and Vicksburg reflects • Mary Hegeler Carus Chancellors. the sacrifices Illinois Page 4 The photographs made to supply up to were taken in a third of the troops • An Interview with Christina April 2013 at who fought in the Heady the Vicksburg campaign. The 47 Page 8 National Illinois 81st Infantry Memorial granite steps represent Military Park, the 47 days of the • Vintage Image Corner 460 miles south of Carbondale. -

Civil War to Civil Rights Commemoration

National Park Service U.S Department of the Interior Washington Support Office: Cultural Resources, Partnerships and Science Interpretation, Education and Volunteers Civil War to Civil Rights Commemoration Summary Report DEDICATION This report honors all those who suffered and died in this nation’s struggles for freedom and equality. It is also dedicated to our colleague, Tim Sinclair, who was taken from us too soon. Timothy D. Sinclair, Sr. (1974-2016) Chief of Interpretation Selma to Montgomery NHT Tuskegee Airmen NHS and Tuskegee Institute NHS You took us on a walk from Selma to Montgomery. To keep your vision and memory alive, “We’re still marching!” Silent sentinels stood watch for 22 hours to commemorate the 22 hours of combat that took place at Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle. FREDERICKSBURG AND SPOTSYLVANIA NMP Cover Graphic: Courtesy of Chris Barr FOREWORD The Civil War to Civil Rights Commemoration has been quite a journey. Thanks to all of you who helped make it a meaningful and memorable one for our country. We hope our efforts have helped Americans understand the connection between these two epic periods of time as a continuous march toward freedom and equality for all–a march that continues still today. Along the way, perhaps the National Park Service learned something about itself, as well. When we first began planning for this commemorative journey, there were several Civil War parks that had difficultly acknowledging slavery as the cause of the war. Both Civil War sites and civil rights sites questioned whether a combined “Civil War to Civil Rights” Commemoration would water down and weaken each. -

Hclassification

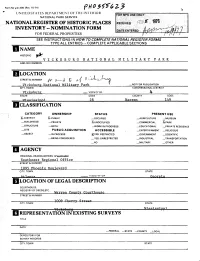

Form No :$ 0-306 (Rev. 10-74) '" UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS, NUMBER jj\f Q^^ £ yj \l c^u-o s^-^-q * " ff Vf rkshiirg National Military.* ParkT)_^.1, vV NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN ' CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Vicksburg __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 28 Warren 149 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X-DISTRICT X_PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE ^UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL _ PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) Southeast Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY, TOWN STATE Af-1 arti-fl VICINITY OF Georgia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Warren County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 1009 CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE -FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2LORIGINAL SITE _XGOOD _RLMNS ^ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL -

12-Mile Al Scheller Hiking Trail Vicksburg National Military Park a Hike Through History

12-Mile Al Scheller Hiking Trail Vicksburg National Military Park A Hike Through History Updated October 2018 Vicksburg Trails Commission A Service Organization to the Youth of America Hiking – ❖ Hikers must maintain a high standard of conduct at all times, are expected Dos and Don’ts to be good stewards of Vicksburg National Military Park, and to be courteous to other visitors while in the park. Hiking Rules ❖ Group leaders are responsible for directly supervising each hiker in the group. At least one adult leader is required to accompany each separate group of hikers so all receive proper supervision. ❖ When hiking on the tour road, use the white striped walking lane. Stay to the right edge of the roadway when no white stripe exists. Hike single file and safely cross roadways as a group. ❖ Carry the proper equipment, including trail guide, rain gear, adequate water, trash bags (everything packed in, must be packed out), first aid kit, cell phones, sunscreen, etc. Please note – the only restroom facilities are located at the Visitor Center on Clay Street and USS Cairo Museum halfway through the park. ❖ Except during medical emergencies (situations requiring immediate emergency medical care), park staff cannot transport private citizens in government vehicles. Assess both the hikers’ physical conditions and the weather before starting! Be realistic in choosing the appropriate hike. It is advised that at least one driver stay with the vehicle(s) should there be a need to pick up and transport the scouts. ❖ Be aware of hazards while hiking – weather, trail conditions, fire ants, snakes, ticks, poison ivy, etc., and take the necessary precautions. -

Salt Creek CWRT

Officers and Members Of The Salt Creek Civil War Round Table Charter Year 1962-1963 Officers Harvey L. Long, * Chairman Mitchell Kostro, * Treasurer Elmhurst, IL Elmhurst, IL N. P. Luginbill, Vice Chairman Mrs. Howard E. Steele, * FOUNDER & Glen Ellyn, IL Secretary, Glen Ellyn, IL The Executive Committee Arthur E. House Dr. Royal K. Schmidt * Glen Ellyn, IL Elmhurst, IL Edwin E. Pile Thomas R. Wiley Elmhurst, IL Bensenville, IL Charter Members Alan C. Aimone Lloyd Hamm John Meitzke Charleston, IL Lombard, IL Lombard, IL Dr. and Mrs. Richard K. Mrs. Fred D. Hancock Allen Rogers Albers, Lombard, IL Glen Ellyn, IL Bensenville, IL H. A. Berens Ralph Hwastecki Mr. & Mrs. Orville H. Ross Elmhurst, IL Lombard, IL Wheaton, IL Mr. and Mrs. Anton J. William C. Jerome J. E. Sheehan Bjorklund, Elmhurst, IL Elmhurst, IL Elmhurst, IL George W. Carlton Corky Kellan Leroy Short Glen Ellyn, IL Lombard, IL Elmhurst, IL Mr. and Mrs. Fred C. Evers Carl Kilian William K. Stock Elmhurst, IL Lombard, IL Lombard, IL Mr. and Mrs. Michael D. Jeff Kincaid Randy Swanson Francis, Itasca, IL Lombard, IL Lombard, IL E. Finch & Grif Dr. P. J. Meginnis Richard H. Tillotson Glen Ellyn, IL Roselle, IL Elmhurst, IL William C. Griffin Mrs. Dorothy Murgatroyd * Spouse is also counted as Wheaton, IL Western Springs, IL a member. 1 Marilyn Steele, a young wife and mother of two children founded the Salt Creek Civil War Round Table in 1962. Harvey L. Long, a member of the Chicago Civil War Round Table, became the first Chairman, or President. The round table was named after the Salt Creek, which runs through many of the communities where its members reside. -

Galena Illinois Guide. Pub:1937

5 a I B RAHY OF THE UNIVERSITY Of ILLINOIS 977.334 F31g cop. 111. HlbL.3ur v< Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/galenaguideOOfede A/~aA^3aDa4^ »: NEWCOMB SOS Nevada St. WftBANA. 1U AMERICAN GUIDE SERIES American Guide Series GALENA GUIDE Compiled and Written by FEDERAL WRITERS' PROJECT (ILLINOIS) Works Progress Administration ivada Si. !A, ILL. Sponsored by THE CITY OF GALENA 1937 Copyrighted, 1937, by The City of Galena ; 777. 33V F 51: «<: 3>U. Wilt . -Mc^o^c^ Foreword 'Towns were never intended as objects of worship, we believe. Surely ours was not. But, if it were possible to have such gods, and if we were compelled to worship none better, we should choose one with a marked character in appearance of hills and valleys, of beetling cliffs and quiet dells, far rather than a city of tame curvatures or of a level plain." —Editorial, Galena Daily Advertiser, 1856. WE whose lives have been shaped against the background of Galena's past may be inclined to accept our birthright as a matter of course without fully realizing that our little town has national signifi- cance as a unique bit of Americana. We have come to regard Galena and its romantic past—its aging buildings with their wealth of architectural treasure—as our personal prize when as a matter of fact it belongs not only to us but to America. We of Galena are merely its custodians, holding it in trust for future generations and for the world beyond our little hills. -

Vicksburg National Military Park: Social Studies Educator's Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 437 314 SO 031 214 TITLE Vicksburg National Military Park: Social Studies Educator's Guide INSTITUTION National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. National Register of Historic Places. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 123p.; For Vicksburg National Military Park Art/Music Educator's Guide, see SO 031 213. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: <http://www.nps.gov/vick/eduguide/edguide.htm>. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Civil War (United States); Elementary Secondary Education; Field Trips; Heritage Education; Historic Sites; Social Studies; *United States History; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Military Combat; Site Visits; *Vicksburg National Military Park MS ABSTRACT This guide seeks to help bring to life the human struggle that was endured in the Campaign for Vicksburg (Mississippi). The guide notes that the Campaign for Vicksburg, which took place between May and July of 1863, was considered the most strategic battle of the Civil War, but it was more than generals and maps, it featured the common soldier, sailor, and civilian who witnessed a lifetime in 47 days. The guide includes information about the park, resources available, and information on planning a field trip. Activities in the guide have age group recommendations for K-12 and each section has supplemental classroom activities. The guide is divided into the -

Donald D. Duhaime Lincoln-Civil War and Nineteenth Century Collection MSS-077A

The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections The University of Toledo Finding Aid Donald D. Duhaime Lincoln-Civil War and Nineteenth Century Collection MSS-077a Size: 21 lin.ft. Provenance: Received from Donald D. Duhaime Access: open Related Collections: Donald D. Duhaime 19th and 20th Century Photograph Collection, 1860s-1940s, Mss-152, Donald D. Duhaime Collection, Mss-077, Alice E. Huebner Collection, Mss-133, Cyrus Hussey Diaries, Mss-017, Weber Family Papers, Mss-126, Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991, Mss-066, Brand Whitlock Collection, Mss-023 Processing Note: Copyright: The literary rights to this collection are assumed to rest with the person(s) responsible for the production of the particular items within the collection, or with their heirs or assigns. Researchers bear full legal responsibility for the acquisition to publish from any part of said collection per Title 17, United States Code. The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections may reserve the right to intervene as intermediary at its own discretion. Completed by: Kristina A. Lininger NOTE: LOCATED AT THE NORTHWEST OHIO BOOK DEPOSITORY Donald D. Duhaime Lincoln-Civil War & Nineteenth Century Collection Historical Sketch Donald D. Duhaime, a University of Toledo 1940 Alumnus and local collector, donated the following collection to the Ward M. Canaday Center. The collection is broken into nine separate series focusing mainly on Abraham Lincoln, the American Civil War, Nineteenth Century books, magazines, and miscellaneous objects, such as sheet music, photographs, albums, and books. The eclectic collection also includes a Presidential section, Ohio History section, Lucas County/Toledo section, and George Custer and American War series. -

Nomination Form for Federal Properties See Instructions in Howto Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries -- Complete Applicable Sections

Form No :$ 0-306 (Rev. 10-74) '" UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OE THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS, NUMBER jj\f Q^^ £ yj \l c^u-o s^-^-q * " ff Vf rkshiirg National Military.* ParkT)_^.1, vV NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN ' CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Vicksburg __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE 28 Warren 149 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X-DISTRICT X_PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE ^UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL _ PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) Southeast Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY, TOWN STATE Af-1 arti-fl VICINITY OF Georgia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Warren County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER 1009 CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE -FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2LORIGINAL SITE _XGOOD _RLMNS ^ALTERED _MOVED DATE. _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL -

2017-04 Knapsack

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table The same rain falls on both friend and foe. April 10, 2017 Volume 17 Our 194th Meeting Number 4 http://www.raleighcwrt.org April 10 Meeting Features John Quarstein Speaking on the Power of Iron Over Wood The Raleigh Civil War Round Table’s April 10 event John is the recipient of the National Trust for Historic will feature award-winning historian, preservationist, Preservation’s 1993 President’s Award for Historic and author John V. Quarstein, who will speak to the Preservation, the Civil War Society’s Preservation group about the USS Monitor. Award in 1996, the UDC’s Jefferson Davis Gold Medal in 1999; and the Daughters of the American John is the director of the USS Revolution Gold Historians Medal in 2009. Monitor Center at The Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport He lives in the historical (1757) Herbert House in News, Virginia. He served as Hampton, Va. historian for the city of Hamp- ton’s 400th anniversary and has previously worked for 30 years as the director of the Virginia ~ USS Monitor ~ War Museum and as consultant to the USS Monitor Center at The USS Monitor, launched in January 1862, was The Mariners’ Museum. designed by Swedish-born inventor John Ericsson and was the first ironclad warship commissioned by His passion for historic preservation is evidenced by the Union Navy. She was nicknamed a “cheesebox the creation of Civil War battlefield parks like the on a raft” due to her unique design. Redoubt Park in Williamsburg and Lee’s Mill Park in Newport News as well as historic house museums such as Lee Hall Mansion and Endview Plantation.