Preface Christmas and the Catholic Consumer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of Divine Worship James M. Starke, Ph.D., Director (703) 224-1653 [email protected] Dr

Office of Divine Worship James M. Starke, Ph.D., Director (703) 224-1653 [email protected] Dr. Richard P. Gibala, Music Coordinator www.arlingtondiocese.org/divineworshipoffice Diocesan Liturgical Commission James M. Starke, Ph.D., Chair (703) 224-1653 [email protected] www.arlingtondiocese.org/diocesanliturgicalcommission Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions (Region IV) National Association of Pastoral Musicians (Arlington Chapter) In the Sacred Triduum, the Church solemnly celebrates the greatest mysteries of our redemption, keeping by means of special celebrations the memorial of her Lord, crucified, buried, and risen ~ Paschal Triduum, 1 (The Roman Missal) The Sacred Paschal Triduum | The Paschal Triduum begins with the Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper and concludes with Evening Prayer on the Sunday of the Resurrection (see Universal Norms on the Liturgical Year, 18-19). Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper Holy Thursday (April 9, 2020) † The only Masses permitted on Holy Thursday are the Chrism Mass and the Evening Mass of Thursday of the Lord’s Supper. With permission of the Bishop, an additional Evening Mass of Thursday of the Lord’s Supper may be celebrated. Funeral Masses, Ritual Masses, Masses for Various Needs, and Votive Masses are not permitted. According to ancient tradition, all Masses without an assembly are forbidden. † For Funerals, Mass is not permitted during the Triduum. However, the body of the deceased may be brought to the church and the Funeral Liturgy outside of Mass may be celebrated † Communion may be received at both the Chrism Mass and the Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper. -

Liturgical Calendar 2020-2021

(S) Solemnity, (F) Feast, (M) Memorial, (M>OM) Memorial reduced to an Optional Memorial (OM) Optional Memorial (*) no assigned rank Liturgical Year – B Lect., Wkday, A/B: Lectionary: Weekday, A (1993) or B (1994) Lect., S&S: Lectionary: Sunday and Solemnities (2009) DECEMBER Calendar 2020 –2021 Series I BG: Book of Gospels (2015) 2020 RL: Lectionary: Ritual Masses, Masses for Various Needs and Occasions, Votive Masses, Masses for the Dead (2014) Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday NOVEMBER NOVEMBER 1st SUNDAY ST. ANDREW (F) ferial ferial ST. FRANCIS XAVIER (M) ferial ferial 29 OF ADVENT 30 1 2 3 4 5 Readings: no. 2, p. 18; BG, p. 12 Readings: Lect., Wkday A, Readings: no. 176, p. 5 Readings: no. 177, p. 7 Readings: no. 178, p. 9, Readings: no. 179, p. 11 Readings: no. 180, p. 13 1st Reading: Isaiah no. 684, p. 605 1st Reading: Isaiah 11.1-10 1st Reading: Isaiah 25.6-10a or no. 685, p. 607 1st Reading: Isaiah 29.17-24 1st Reading: Isaiah 30.19-21, 23-26 63.16b-17; 64.1, 3-8 1st Reading: Romans 10.9-18 Gospel: Luke 10.21-24 Gospel: Matthew 15.29-37 1st Reading: Isaiah 26.1-6 Gospel: Matthew 9.27-31 Gospel: Matthew 2nd Reading: 1 Corinthians 1.3-9 Gospel: Matthew 4.18-22 Gospel: Matthew 7.21, 24-27 OM: St. John Damascene 9.35 – 10.1, 5a, 6-8++ Gospel: Mark 13.33-37 IMMACULATE 2nd SUNDAY ST. AMBROSE (M) CONCEPTION OF THE ferial ferial ferial OUR LADY OF 6 OF ADVENT 7 8 BLESSED VIRGIN MARY (S) 9 10 11 12 GUADALUPE (F) Readings: no. -

Resources for Celebrating the Easter Season at Home

Resources for Celebrating the Easter Season at Home Following the celebration of Holy Week, the resources included here are available to aid in the celebration of the Easter season at home. In this current period of uncertainty, “social distance,” and distance from our Lord in the Eucharist, the Resurrection of Christ at Easter provides for us all a sign of great joy and hope. Let us live “the joy of the Gospel” this Easter, which, as Pope Francis reminds us, “fills the hearts and lives of all who encounter Jesus.” Let that be our testimony to the world in a time of trouble not only on Easter Sunday, but as we celebrate each of the 8 days of Easter Week (Easter Sunday through Divine Mercy Sunday) and throughout the 50 days of the Easter season that follow. Suggestions for the Easter Season For families with younger children: • Downloadable and printable Easter Calendar • Three simple ways to celebrate from GetFed.com • Six creative ways to teach the Easter story from Catholic Icing • Catholic All Year has a blog post with great ideas for gifts, decorations and activities at home for this year For families with teens: • yDisciple series on the Creed, especially episodes 4-7 • Life Teen: • Virtual “Life Nights” • Small group Bible studies • Video series on Sundays of the Easter season • YM360: Youth Group at Home • Find Easter themed playlists like this one to help elevate your celebrations with joyful Christian music For adults: • Bishop Barron on the meaning of Easter and Podcast Q&A • Loyola Press: Jesus is Alive and Why Easter is On -

Octave of Easter Prayer Service for Catholic Educators INTRODUCTION Good Morning, and Welcome to Our Prayer Service to Begin Our Meeting During This Octave of Easter

Octave of Easter Prayer Service for Catholic Educators INTRODUCTION Good morning, and welcome to our prayer service to begin our meeting during this Octave of Easter. Our days of rejoicing continue from Easter Sunday with a week in which each day is a solemnity – the highest form of celebration in the Church’s liturgical year. OPENING SONG In the spirit of this joyful season, please join in our opening song: OPENING PRAYER Let us begin our prayer: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen God our Father, basking in the radiant hope of your risen Son, we turn to you now with Easter joy. Open our hearts to hear your holy word, that it may shape and direct our work this day and always in the service of Catholic education. We make this prayer to you in the name of Jesus, the Lord. Amen. READING (Any Mass reading from the Octave of Easter will be suitable) PRAYER OF THE FAITHFUL 1. Let us pray for the Church. That in this Easter season, all who share a common Baptism will find greater unity in their shared joy of Christ’s resurrection. We pray to the Lord… Lord, hear our prayer. 2. Let us pray for the world. That peoples of all nations will open their hearts to the victorious and risen Christ’s gift of peace. We pray to the Lord… Lord, hear our prayer. 3. Let us pray for those who struggle to experience the joy of Easter in their lives. -

COMPLETION of the OCTAVE of CHRISTMAS the FEAST of the HOLY FAMILY the SOLEMNITY of the MOTHER of GOD …………………………………………………………………… Sun

COMPLETION OF THE OCTAVE OF CHRISTMAS THE FEAST OF THE HOLY FAMILY THE SOLEMNITY OF THE MOTHER OF GOD …………………………………………………………………… Sun. The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary & Joseph Dec. 30 ARE YOU SEEKING JESUS WHOLE HEARTEDLY? A reflection by Origen of Alexandria Mon. Seventh Day in the Octave of Christmas 31 FINDING THE JOY THAT ONLY JESUS BRINGS A reflection by Fr. Geoffrey Preston Tues. SOLEMNITY OF MARY, MOTHER OF GOD Jan. 1 HOW SERIOUS ARE YOU ABOUT UNITY WITH JESUS? A reflection from a homily by Basil of Seleucia Wed. Memorial of Sts. Basil the Great & Gregory Nazianzen 2 WHAT IS LIVING IN THE SPIRIT? A reflection by St. Basil the Great in his Treatise on the Spirit Thurs. Thursday before the Epiphany 3 TWO STAGES IN CELEBRATING CHRIST’S COMING A reflection from a homily by St. Pope John XXIII Fri. Memorial of St. Elizabeth Ann Seaton 4 JESUS’ CALL TO PRACTICAL CHARITY The Daughters of Charity constitutions by St. Elizabeth Ann Seaton Sat. Memorial of St. John Neuman 5 SEEKING TOTAL DEDICATION TO GOD’S SERVICE From the Seminary Diary of St. John Neumann ARE YOU SEEKING JESUS WHOLE HEARTEDLY? A reflection from a Commentary on Luke by Origen of Alexandra How often have we heard the Gospel tale of Jesus going about his business and of Mary and Joseph reacting, as any parent would, by thinking he was lost. They had been in Jerusalem for the Passover and Jesus was of an age to enter solemnly into the life-long and personal obligation to keep all that God asks of those who have accepted a covenant to love God with all their heart, and mind and strength. -

The Holy Family (Sunday Within the Octave of Christmas) 27 December

About the Holy Family The Holy Family Our knowledge of the Holy Family comes to us from the Gospel accounts. This feast, which was established in 1921, celebrates the unity and love so evident in the family of Joseph, Mary and (Sunday within the Octave Jesus. of Christmas) 27 December What can we learn from the Holy Family? The Church teaches us about the “Domestic Church”, the Church of a family living in a household. What a beautiful image of a family. Yes, Christ dwells in our families and homes as well. In our time and place when family and family values are challenged, we must look to the Holy Family for guidance on how to live our lives in our families even when our parents and/or siblings challenge us and our kind nature. The Holy Family who experienced difficulties and social pressures of their time, are a model for Christian family life in our day and age. When we are dismissed from Mass, we take Christ in our families so that we share his love with the people whom we live with. Collect O God, who were pleased to give us the shining example of the Holy Family, graciously grant that we may imitate them in practising the virtues of family life and in the bonds of charity, and so, in the joy of your house, delight one day in eternal rewards. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, for ever and ever. Amen. -

The Life and Death of Sir Thomas More, Knight by Nicholas Harpsfield

The Life and Death of Sir Thomas More, Knight by Nicholas Harpsfield icholas Harpsfield (1519–1575) com- Clements, and the Rastells. With Mary’s ac- Npleted this biography ca. 1557, during cession to the throne in 1553, he returned and the reign of Queen Mary, but it was not pub- became archdeacon of Canterbury and worked lished until 1932. Indebted to William Rop- closely with Cardinal Reginald Pole, the Arch- er’s recollections, Harpsfield’s Life presents bishop of Canterbury. With Mary’s and Pole’s More as both a spiritual and secular figure, and deaths in 1558, and with his refusal to take the Harpsfield dedicates his biography to William oath recognizing Queen Elizabeth’s suprem- Roper, presenting More as the first English acy, Harpsfield was imprisoned from 1559 to martyr among the laity, who serves as an “am- 1574 in Fleet Prison where, as he relates in his bassador” and “messenger” to them. Dedicatory Epistle, William Roper supported Harpsfield was born in London, and was ed- him generously. ucated at Winchester and then New College This edition of Harpsfield’s Life is based on at Oxford where he became a perpetual fellow the critical edition published for the Early En- and eventually earned a doctorate in canon glish Text Society (EETS) in 1932 by Oxford law. In 1550, during the reign of Edward VI, University Press, edited by E. V. Hitchcock; he moved to Louvain and come to know many the cross-references in the headnotes refer to in the More circle such as Antonio Bonvisi, the this edition. -

The Octave of Easter

The Octave Day of Easter The Second Sunday of Easter was already a solemnity as the Octave Day of Easter; nevertheless, the title “Divine Mercy Sunday” does highlight and amplify the meaning of the day. In this way, it recovers an ancient liturgical tradition, reflected in a teaching attributed to St. Augustine about the Easter Octave, which he called “the days of mercy and pardon,” and the Octave Day itself as “the compendium of the days of mercy.” For a much deeper understanding of the Octave Day of Easter in the ancient liturgical tradition, especially in the earliest liturgical document, in existence, directly attributed to the Apostles, “The Apostolic Constitutions”, and St. Gregory Nazianzen, see the essay by Father Seraphim Michalenko, M.I.C., in “Divine Mercy, the Heart of the Gospel”, published by the John Paul II Institute of Divine Mercy or in this handy leaflet “Mercy, the Message of Easter”. Moreover, it is well known that the title “Divine Mercy Sunday” expresses the message of the prayers and readings traditionally appointed for this Octave Day. Liturgically the day has always been centered on the theme of Divine mercy and forgiveness. That is why in its decree establishing Divine Mercy Sunday, the Holy See, strictly insisted, that the texts already assigned for that day in the Missal and the Liturgy of the Hours of the Roman Rite “are always to be used for the liturgical celebration of this Sunday.” The Octave Day of Easter, Divine Mercy Sunday, therefore points us to the merciful love of God, and the forgiveness of sins, that lies behind the whole Paschal Mystery – the whole mystery of the death, burial and resurrection of Christ – made present for us in the Eucharist. -

The Tridentine Mass / 1984 Editorial

TRIDENTINE MASS On October 3, 1984, the Sacred Congregation of Divine Worship issued a letter concerning the limited use of the Tridentine Mass. This is the text of the letter: Four years ago, at the direction of Pope John Paul II, the bishops of the entire Church were invited to submit a report on the following topics: The manner in which the priests and the people of their dioceses, in observance of the decrees of Vatican Council II, have received the Roman Missal promulgated by author ity of Pope Paul VI; Problems arising in connection with the implementation of the liturgical reform; Opposition to the reform that may need to be overcome. The results of this survey here reported to all the bishops (See Notitiae, No. 185, December 1981). Based on the responses received from the bishops of the world, the problem of those priests and faithful who had remained attached to the so-called Tridentine rite seemed to have been almost completely resolved. But the problem perdures and the pope wishes to be responsive tv such groups of priests and faithful. Accordingly, he grants to diocesan bishops the faculty of using an indult on behalf of such priests and faithful. The diocesan bishop may allow those who are explicitly named in a petition submitted to him to celebrate Mass by use of the 1962 Roman Missal. The following norms must be observed: A. There must be unequivocal, even public evidence that the priest and people petition ing have no ties with those who impugn the lawfulness and doctrinal soundness of the Roman Missal promulgated in 1970 by Pope Paul VI. -

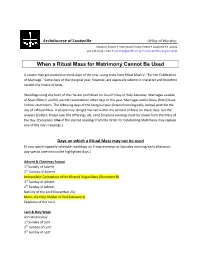

When a Ritual Mass for Matrimony Cannot Be Used

Archdiocese of Louisville Office of Worship Maloney Center 1200 South Shelby Street Louisville KY 40203 502-636-0296 x1260 [email protected] www.archlou.org/worship When a Ritual Mass for Matrimony Cannot Be Used A couple may get married on most days of the year, using texts from Ritual Mass V: “For the Celebration of Marriage.” Some days of the liturgical year, however, are especially solemn in character and therefore restrict the choice of texts. Weddings using any form of the rite are prohibited on Good Friday or Holy Saturday. Marriages outside of Mass (Rites II and III) are not restricted on other days of the year. Marriages within Mass (Rite I) have further restrictions. The following days of the liturgical year (listed chronologically, below) prohibit the use of a Ritual Mass. A couple may still get married within the context of Mass on these days, but the prayers (Collect, Prayer over the Offerings, etc.) and Scripture readings must be drawn from the Mass of the Day. (Exception: One of the starred readings from the Order for Celebrating Matrimony may replace one of the day’s readings.) Days on which a Ritual Mass may not be used (If your parish typically schedules weddings on Friday evenings or Saturday morning/early afternoon, pay special attention to the highlighted days.) Advent & Christmas Season 1st Sunday of Advent 2nd Sunday of Advent Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary (December 8) 3rd Sunday of Advent 4th Sunday of Advent Nativity of the Lord (December 25) Mary, the Holy Mother of God (January 1) Epiphany of the Lord Lent & Holy Week Ash Wednesday 1st Sunday of Lent 2nd Sunday of Lent 3rd Sunday of Lent 4th Sunday of Lent 5th Sunday of Lent St. -

The Following Comments from Liturgical Law and Documents May Be Helpful

LiturgyNotes – February 2009 Agnoli Page 1 of 7 Dear companions at the Table, With this issue of the LiturgyNotes, I would like to thank Deacon Bob McCoy for his over 5- years of service on the Diocesan Liturgical Commission. At our last meeting, Deacon Bob expressed his desire to retire from the Commission and his request was granted by Bishop Amos. His love for the prayer and people of the Church is evident, and the wisdom and experience which he brought to our deliberations and discussions will be missed. Thank you, Bob. In order to foster better communication and collaboration with the Hispanic Ministry Vicariate, Father Bernie Weir will be joining us on the Commission. I am grateful for his willingness to serve in this capacity and am looking forward to our working together. Deacon Frank Agnoli, MD, MDiv, MA Director of Liturgy & Director of Deacon Formation E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: 563-324-1912 x255 FOR YOUR INFORMATION… LENTEN FAST AND ABSTINENCE FAST—Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are days of fast. On days of fast, one full meal and two lesser meals are allowed. Eating between meals is not permitted. Catholics between the ages of 18 and 59 are bound to fast. ABSTINENCE—Ash Wednesday and all of the Fridays of Lent are also days of abstinence. On days of abstinence, meat may not be taken. The law of abstinence binds all Catholics fourteen years of age or older. If members of the Faithful are unable to observe the fast and abstinence regulations because of ill health or other reasons, they are urged to practice other forms of penance and self-denial suitable to their condition. -

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents 128 West 37Th

Founded 1866 The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Week of December 23, 2018 Mass Intentions SUNDAY, DECEMBER 23 - FOURTH SUNDAY OF ADVENT 09:00 - Pro Populo 10:30 - Christmas Novena LATIN TRIDENTINE MASS CORNER 12:30 - Serafin Aurelio (d) Calendar MONDAY, DECEMBER 24 - LATE ADVENT WEEKDAY December 23 - Fourth Sunday of Advent st 1 Class - Chant Mass 07:00 - Ava Eliza Geo (L) 07:30 - Holy Souls in Purgatory December 24 - Vigil of Christmas 12:15 - Kathleen Oertli (d) 1st Class - High Mass 01:15 - The Pruszynscy and Kuleszow Family (d) December 25 - The Nativity of Our Lord 04:00 - Christmas Novena 1st Class - High Mass TUESDAY, DECEMBER 25 - THE NATIVITY OF THE LORD December 26 - St. Stephen, Deacon & Protomartyr (CHRISTMAS) with Commemoration of Day in the 12:00 - Pro Populo Octave of Christmas 01:30 - The Chang Family (L) nd 2 Class - High Mass 9:00 - St. Anthony 10:30 - Cecilia Tan and Family (L) December 27 - St. John, Apostle & Evangelist with 12:30 - Christmas Novena Commemoration of the Day in the 05:00 - Anthony Terrill, Jr. (d) Octave of Christmas nd WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 26 - St. Stephen, the first Martyr 2 Class - High Mass 07:00 - Christmas Novena (L) December 28 - Holy Innocents with 07:30 - Alton Goad, Jr. (d) Commemoration of the Day in the 12:15 - Brian Ahern (d) Octave of Christmas 01:15 - Hilaria Marcelo (d) 1st Class - Solemn High Mass 06:00 - Deceased Family Members of Cecilia Tan December 29 - 5th Day in the Octave of Christmas THURSDAY, DECEMBER 27 - St.