Robert Rusk May 24Th, 2000 Bloomington, Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Band Director's Catalog

BAND DIRECTor’s CATALOG We make legends. A division of Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. P.O. Box 310, Elkhart, IN 46515 www.conn-selmer.com AV4230 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Eb Soprano, Harmony & Eb Alto Clarinets ....... 10 Bb Bass, EEb Bass & BBb Bass Clarinets ........... 11 308 Student Instruments Step-Up & Pro Saxophones .............................. 12-13 Step-Up & Pro Bb Trumpets .............................. 14 Piccolos & Flutes ...................................................... 1 Step-Up & Pro Cornets ..................................... 14 Oboes & Clarinets .................................................... 2 C Trumpets, Harmony Trumpets, Flugelhorns .... 15 Saxophones .............................................................. 3 Step-Up & Pro Trombones ................................ 16-17 204 Trumpets & Cornets .................................................. 4 Alto, Valve & Bass Trombones .......................... 18 Trombones ............................................................... 5 Double Horns .................................................. 19 PICCOLOS Single Horns ............................................................ 5 Baritones & Euphoniums .................................. 20 Educational Drum, Bell and Combo Kits .................. 6 BBb Tubas - Three Valve .................................... 21 ARMSTRONG Mallet Instruments .................................................... 6 BBb & CC Tubas - Four Valve ............................ 21 204 “USA” – Silver-plated headjoint and body, silver-plated -

For Release at NAMM 2014 December 3, 2013 Conn-Selmer Is Proud to Announce Its 2014 Launch Line-Up Flutes Saxophones

For Release At NAMM 2014 December 3, 2013 Conn-Selmer is Proud to Announce Its 2014 Launch Line-Up 2014 is going to be a big Music industry year and Conn-Selmer is excited to share these newly, innovated instruments that will invigorate its core categories. Flutes Announcing the new PCR Headjoint. All flute models in the Armstrong line will have the new headjoint. PCR represents increased: Projection Clarity and Response. This new headjoint has the familiar Armstrong durability that everyone loves, with improved sound and playability. Armstrong is Made in the USA and the new headjoints on all models street price ranges from $994 - $1,449. Models are: 102, 102E, 103, 103OS, 104, 303B, 303BOS, 303BEOS, 800B, 800BOF, 800BEF, 800BOFPICC, FLSOL301 and FLSOL201G. Saxophones Revealing the new Selmer Tenor Saxophone, model TS44. This custom designed Henri Selmer Paris neck and mouthpiece comes with a BAM case. With this natural addition, it expands the highly successful 40 Series. MAP is $2,899 and also comes in black nickel (pictured) and silver plate. Both the TS44B and TS44S MAP for $3,265. Trombones Bach Artisan has extended its line of professional trombones. The Artisan Collection is customizable with fully interchangeable components and can become 81 different horns! This horn is adaptable to a variety of trombone artists. You can choose from three (3) bell material options, three (3) valve options, three (3) hand slide options and three (3) tuning slide options, to make it your own sound. It comes in standard models A47 (MAP is $2,758), A47I and A47MLR (MAP is $4,487). -

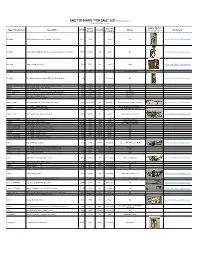

FOR SALE" LIST (UPDATED 12/6/13) [email protected]

ERIC TOTMAN'S "FOR SALE" LIST (UPDATED 12/6/13) [email protected] Year or Over-All Link to Photos Type Of Instrument Description PRICE Serial # Extras (Click on photo to see For Sale At: Decade Condition more photos) Alto Horn Boston Musical Instrument Company Eb Alto Horn $225 1903 Good No www.HornCollector1.WebStore.com Alto Horn Charles Mahillon Eb Alto Horn that was probably made in the 1890's $275 1890's? N/A Good No www.HornCollector1.WebStore.com Alto Horn Henri Pouisson Alto Horn $150 1900? N/A Good Case www.HornCollector1.WebStore.com Alto Horn H.N. White King "F" Alto Horn $250 1948 296313 Very Good Case & Mouthpiece Alto Horn York Band Instrument Company Eb ToneKing Alto Horn $150 0 0 Very Good No www.HornCollector1.WebStore.com Baritone - OTS Saxhorn John Stratton Baritone "Over-The-Shoulder" Saxhorn $7,000 1860's N/A Very Good No Baritone Lyon & Healy "Beau Ideal" Baritone $250 1890's? N/A Good No Baritone J.W. Pepper Baritone $50 1880's 14207 Poor No Bugle - Indian War Civil War / Indian War Era Bugle made of German Silver $350 1860's-1870's N/A Very Good Mouthpiece Bugle - WWI WWI Trench Bugle made by Grand Rapids Band Inst. Co. $75 1910's N/A Good Mouthpiece Bugle Horsmann Company Bugle $150 1880's? N/A Very Good Mouthpiece Bugle Rudall, Rose, Carte & Co Bugle $200 1858-1871 N/A Good Case Bugle - Keyed Bb Keyed Bugle with 6 keys (Maker not known) $3,500 1830's-1850's N/A Excellent Mouthpiece and tunable tuning bit www.HornCollector1.WebStore.com Cornet Bb/A Cornet - Maker Unknown $250 1880's? N/A Very Good Case, A lead pipe, Bb lead pipe, lyre Cornet Ball, Beavon & Cie. -

Acquiring a Band Instrument for Your Child

Acquiring a Band Instrument for your Child Rental: Don Wilson music rents new, quality band instruments that are covered under a protection program (insurance). It is a rent-to-own program. Rent prices are $25/month for a percussion kit, $30 for flute & clarinet, $45 for alto sax, $55 for oboe, tenor sax, french horn and euphonium. The rental agreement is on a monthly basis and the rental instrument can be returned at any time. PROS: new, high quality instrument, no maintenance/repair expenses, month-by-month lease, equity is often transferable to a different instrument (step-up model or complete change). CONS: usually more expensive in the long run, unpaid or delinquent accounts result in repossession. Purchase: Purchasing a band instrument can be a big investment. Parents should purchase an instrument if they are confident that their child will stick with that instrument for a considerable amount of time. There are many quality dealerships in Kentucky such as Don Wilson Music, Hurst Music and Buddy Rogers that offer school band instruments. There are also online music dealers such as Woodwind & Brasswind (http://www.wwbw.com). Used instruments are available on Craigslist and Ebay. Please beware of instruments that are exponentially cheaper than those of their competitors. These instruments are generally unable to be properly tuned, and most music repair businesses will not service them. Instruments that are offered in flashy colors are almost always of sub-par quality. Please see the table on the back of this for a listing of reputable instrument brands. PROS: less expensive overall cost than rental, quality used instruments can pose a significant savings, wide selection. -

Trumpets That Work / 2014 Calendar C.G.Conn Wonder Solo Alto DESIGNED for BRASS BAND PLAYERS to PLAY the HIGHEST Eb ALTO PARTS

Trumpets That Work / 2014 Calendar C.G.Conn Wonder Solo Alto DESIGNED FOR BRASS BAND PLAYERS TO PLAY THE HIGHEST Eb ALTO PARTS Charles Gerard Conn Advertisement (1844-1931) fought in the from the Civil War as a member December, 1902 This diagram from of the Union Army. He edition of C.G. the US patent later organized the 1st Conn’s Truth (#343888) issued Regiment of Artillery in depicting the to C.G. Conn for what is now the Indiana Solo Alto. Truth the “Wonder Guard Reserve. He was was a marketing Valve”, illustrates promoted from within vehicle for his innovation of the ranks to eventually the company, removing some of become their first combining the sharp bends in Colonel, a military title catalog images the shape of the that stayed with him for with numerous airway through the Image courtesy Nick DeCarlis Image courtesy Mark Metzler the rest of his life. testimonials. valve casing. ©2013 TrumpetMultimedia, LLC This instrument is technically an Eb alto horn, an instrument most often used in for brilliancy of tone, quick, tight valve action, perfect tuning in all keys, solid Frank Olds and Henry Martin. Conn’s flamboyant personality helped him to achieve brass bands to play inner parts. Within the brass band instrumentation, three parts construction, handsome finish, and the display of skilled workmanship in every other successes that included the founding of a newspaper that still exists today as are written for the alto or tenor horn. The highest of these parts is the “Solo Alto” feature.” When it was engraved and silver plated as pictured, the price for this The Elkhart Truth. -

How Do I Get My Instrument?

Shakopee Beginning Band How do I get my instrument? INSTRUMENT INFORMATION Shakopee Public Schools 2017-18 HOW DO I GET AN INSTRUMENT FOR MY CHILD? *JOIN US FOR OUR INSTRUMENT INFORMATION NIGHT: AT SUN PATH ELEMENTARY ON APRIL 25TH FROM 4:00-7:30. Most of our students get their instruments from one of the following options. Please read the “other instruments” section below if you are not planning on going through a recommended music store. Buying an instrument can be very intimidating! Please ask your director for assistance if you are unsure of what and where to buy. FAMILY-OWNED INSTRUMENTS If you already have an instrument at home, this would be a great, low-cost way for your child to get started in band. However, it is extremely important that your child’s instrument be in good playing condition. The older the instrument, the more likely it is that it will need some repair work before it is playable. If you are planning to have your child play a family-owned instrument, we recommend bringing it to a music repair shop for a check-up before Band Display Night on May 17 to be sure it is in good playing condition. A list of repair shops is below. ECKROTH MUSIC (651) 704-9654 GROTH MUSIC (952) 884-4772 SCHMITT MUSIC (763) 398-5035 MIDWEST BAND INSTRUMENT SERVICE (952) 884-0917 SCHOOL-OWNED INSTRUMENTS If your child chooses to play F Horn, Baritone/Euphonium, or Tuba, he/she will rent an instrument from the school. The cost is $60 per year and is non-refundable. -

Section 3: Music and Art Equipment

Section 3: Music and Art Equipment Anderson, Boyd H. High School 299,969.90 Instrument Qty Unit Price Total Vendor Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A002.102 2 1,491.00 2,982.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A004.102 5 1,358.00 6,790.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A005.101 3 2,030.00 6,090.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A008.101 1 791.00 791.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A010.101 2 1,026.00 2,052.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A011.101 3 1,082.00 3,246.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A013.101 1 910.00 910.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A014.101 2 1,026.00 2,052.00 Wenger Corporation Acoustic Cabinet-Wenger-255A912.102 1 1,358.00 1,358.00 Wenger Corporation Alto Saxophone Performing-Selmer-AS42M 2 2,296.63 4,593.26 All County Music Alto Saxophone Training-Yamaha-YAS200AD 20 955.80 19,116.00 All County Music Baritone Saxophone-Conn-Selmer-SBS280R 1 4,314.94 4,314.94 All County Music Bass Clarinet-Yamaha-YCL221II 1 1,663.93 1,663.93 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 18"-Yamaha-MN8318FWC 1 613.44 613.44 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 20"-Yamaha-MB8320FWC 1 642.24 642.24 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 22"-Yamaha-MB8322FWC 1 683.52 683.52 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 24"-Yamaha-MB8324FWC 1 720.00 720.00 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 26"-Yamaha-MB8326FWC 1 748.80 748.80 All County Music Bass Drum Marching 28"-Yamaha-MB8328FWC 1 776.64 776.64 All County Music Bass Trombone-Yamaha-YBL620G 1 2,759.75 2,759.75 -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 30-Sep-2008 I, Donald Scott Moore , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone It is entitled: The Concerto for Bass Trombone by Thom Ritter George and the Beginning of Modern Bass Trombone Solo Performance Student Signature: Donald Scott Moore This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Timothy Anderson, MM Timothy Anderson, MM Randy Gardner, BM Randy Gardner, BM Wesley Flinn Wesley Flinn 11/3/2009 244 The Concerto for Bass Trombone and Orchestra by Thom Ritter George and the Beginning of Modern Bass Trombone Solo Performance A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Musical Arts (D.M.A.) in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Donald Scott Moore B.S. Ed., Jacksonville State University, 1984 B.A., Jacksonville State University, 1984 M.M., University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music, 1988 September, 2009 Committee Chair: Timothy Anderson ABSTRACT This paper examines the literature for bass trombone of the late 1950s and early 1960s in order to establish Thom Ritter George’s Concerto for Bass Trombone as a pivotal work that signaled an abrupt change not only in how composers regarded the instrument, but also what technical demands were expected of players. In the first portion of this paper, music of the past is examined to show that the mechanical developments of the past had a direct influence on the music written for the instrument. -

The Following Is a List of Trusted and Reputable Musical Instrument Brands

BEWARE OF ISOs (Instrument-Shaped Objects) These are the cheap instrument-shaped objects found on online auctions, other internet sources, and large chain stores. Although we will refrain from mentioning specific stores, keep in mind that if you can also buy toilet paper, jeans, or tires from the store, then it is not a music store, and it will not have musically knowledgeable personnel. You get what you pay for. If it’s inexpensive, it’s not a quality instrument. A bad instrument is be harder to play in tune and with good tone quality, will likely produce a non-standard instrument sound, will not blend well in the band, will be impossible to repair correctly, and will almost always frustrate the student to the point of eventually quitting. Many repair people refuse to work on these instruments, because they cannot guarantee the results. A good quality student instrument made by a respected manufacturer, with proper care, can last throughout middle school, high school, and beyond. If after looking at the list below, you still have questions about a particular instrument brand, please contact me. The following is a list of trusted and reputable musical instrument brands. This list is not exclusive, but you are much more likely to do well if you choose an instrument from one of these manufacturers. Flute: Armstrong, Artley, Avanti, Bundy, Carnegie XL (CXL), Emerson, Gemeinhardt, Jupiter, Olds, Pearl, Selmer, Yamaha Oboe: Bundy, Carnegie XL (CXL), Fox, Jupiter, Loree, Olds, Renard, Selmer, Yamaha Bassoon: Amati, Bundy, Fox, Jupiter, Olds, -

Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. 2005 Annual Report

2005 annual report extending our reach Contents p3 Letter to Shareholders p9 Form 10-K p11 Business Description p17 Risk Factors p25 Selected Consolidated Financial Data p26 Management’s Discussion & Analysis p38 Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm p39 Consolidated Financial Statements p43 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements p73 Management’s Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting p81 Shareholder Information Corporate Profile Steinway Musical Instruments, through its operating subsidiaries, is a world leader in the design, manufacture and marketing of high quality musical instruments. The Company has one of the most valuable collections of brands in the music industry. Through a worldwide network of dealers, Steinway Musical Instruments’ products are sold to professional, amateur and student musicians, as well as to orchestras and educational institutions. The Company employs a workforce of over 2,400 and operates 14 manufacturing facilities in the United States and Europe. Financial Highlights (In thousands except per share data) 2005 2004 Change Net Sales $ 387,143 $ 375,034 3% Grossss MarginM 28.8% 29.1% Operatingrating IncomeI $ 34,837 $ 34,241 2% Adjustedsted EBITDAEBITD 1 49,015 50,842 -4% Net Income 13,792 15,867 -13% Earningsnings Per Share – BasicBas $ 1.71 $ 1.97 -13% Earningsnings Per Share – Diluted 1.67 1.91 -13% Book Value Per Share2 $ 18.34 $ 18.1318 1% Free Cash Flow3 $ 26,425 $ 18,6871 41% Total Debt $ 204,692 $ 222,792 -8% Less Cash (34,952) (27,372) Net Debt $ 169,749,740 $ 195,420 -13% 1 Adjusted EBITDA represents earnings before net interest expense, income taxes, depreciation and amortization, excluding adjustments for non-recurring, infrequent or unusual items. -

(London Nomenclature!) Modele Anglais Cornet—Forerunner of Besson's (Paris) Concertiste Model, and Thence the Modern Cornet

362 HISTORIC BRASS SOCIETY JOURNAL Figure 14. Besson Desideratum (London nomenclature!) modele anglais cornet—forerunner of Besson's (Paris) Concertiste model, and thence the modern cornet. Paris (92 rue d'Angouleme), serial no. 7125 (early 1870s); bell length 12'12" (ca. 32.4 cm.); restoration by Frank Griesemann; authors coll. ELDREDGE 363 There were, of course, other models by other makers, but few instruments survive to lend substance to catalogue descriptions and illustrations. Many makers produced their variant versions of Courtois single-lever double-water-key and Besson single-water-key models, sometimes referring to them (not always accurately!) as their "Courtois" and "Besson" models. Some copies of Besson designs (usually, though not necessarily, cheaper instruments) eliminated the second, high/low pitch slide, and often had a soldered joint connecting the first and third 180° bends of the leadpipe. When the English firms of Hawkes and Son, Higham, and Boosey and Company (who bought out Henry Distin in 1868) began manufacturing their own high-quality instruments, their models were patterned closely after especially Courtois, but also Besson. These models had evidently become established in the cornet-purchasing public's mind as the standard, in both form and quality, so that little deviation from the standard few designs was apparently possible up through to the end of the century. Similarly, when musicians in the United States began to abandon string-action rotary models in favor of Perinet-valved instruments, manufacturers such as Lehnert, Fiske, Conn, Boston Musical Instrument Manufactory, Standard Band Instrument Company, Missenharter, etc. likewise produced more-or-less faithful copies of Courtois and Besson instruments. -

E Ledgers & Serial Number Books

LOOKING BACK BY KEN DROBNAK e Ledgers Serial Number& Books of Frank Holton & Company Researchers will be evaluating the information in these books for years. When may they be available for everyone else? ollectors and musical instrument researchers commonly set Further, “dates may not be consecutive due to different finish types up searches on Craigslist, eBay and other websites looking being interspersed throughout the list, which would suggest that orders for that new “find.” Late last year, a 1906 Holton euphonium could not be added chronologically to the ledgers.” Another issue is that was listed on eBay for a starting bid of one hundred dollars random entries were added outside of the original time span, such as Cplus shipping. Thoughts of, “Could that be one of the first Holton in Image 2. This page shows instruments manufactured in 1900, though euphoniums?” ran through my mind. The picture on the seller’s webpage matched the style of early Holton euphoniums and the serial number, there is a flute sale noted from 1940 (or is it 1946?). 2289, indicated a 1906 date. That seemed a bit late to be “one of the first” The first euphonium listed in the ledgers is number 979, shown in Holton euphoniums. But how can any collector or researcher confirm an Image 3. The first tuba listed, which is at the museum, is number 1020, instrument’s age? There are several websites with Holton serial number shown in Image 4. By now, you might be wondering what is listed as lists and estimated dates of manufacture, but the original ledgers would number 001; unfortunately for our discussion today, the lowest number be the authoritative source.