Why SA Sprinters Are Starting to Push the Boundaries a String of Top

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

START LIST 200 Metres Men - Round 1 First 3 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 3 Fastest (Q) Advance to the Semi-Finals REPLACEMENT DRAW

REVISED London World Championships 4-13 August 2017 START LIST 200 Metres Men - Round 1 First 3 in each heat (Q) and the next 3 fastest (q) advance to the Semi-Finals REPLACEMENT DRAW RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 20 Aug 2009 Championships Record CR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM 23 Berlin (Olympiastadion) 20 Aug 2009 World Leading WL 19.77 Isaac MAKWALA BOT 31 Madrid (Moratalaz) 14 Jul 2017 i = Indoor performance Heat 1 7 7 August 2017 18:30 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Teray SMITH BAH 28 Sep 94 20.25 20.25 3 Serhiy SMELYK UKR 19 Apr 87 20.30 20.42 4 Mohamed ALSADI OMA 24 Feb 94 21.02 21.12 5 Bernardo BALOYES COL 6 Jan 94 20.11 20.11 6 Yohan BLAKE JAM 26 Dec 89 19.26 19.97 7 Alex WILSON SUI 19 Sep 90 20.37 20.37 8 Abdul Hakim SANI BROWN JPN 6 Mar 99 20.32 20.32 Heat 2 7 7 August 2017 18:38 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Jereem RICHARDS TTO 13 Jan 94 19.97 19.97 3 Ifeanyi OTUONYE TKS 27 Jun 94 21.39 21.66 4 Jeffrey JOHN FRA 6 Jun 92 20.31 20.31 5 Mark Otieno ODHIAMBO KEN 11 May 93 20.41 20.41 6 Jonathan QUARCOO NOR 13 Oct 96 20.39 20.39 7 Kyree KING USA 9 Jul 94 20.27 20.27 8 Rasheed DWYER JAM 29 Jan 89 19.80 20.11 Heat 3 7 7 August 2017 18:46 START TIME LANE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH PERSONAL BEST SEASON BEST 2 Aldemir DA SILVA JUNIOR BRA 8 Jun 92 20.15 20.15 3 Alonso EDWARD PAN 8 Dec 89 19.81 20.74 4 Sibusiso MATSENJWA SWZ 2 May 88 20.58 20.58 5 Ján VOLKO SVK 2 Nov 96 20.33 20.33 6 Burkheart -

Monaco 2017: Full Athletes' Bios (PDF)

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 21.07.2017 Start list 100m Time: 21:35 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Omar MCLEOD JAM 9.58 9.99 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.97 9.97 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 3 Chijindu UJAH GBR 9.87 9.96 9.98 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Usain BOLT JAM 9.58 9.58 10.03 NR 10.53 Sébastien GATTUSO MON Dijon 12.07.08 5 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.92 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene 13.06.14 6 Christopher BELCHER USA 9.69 9.93 9.93 MR 9.78 Justin GATLIN USA 17.07.15 7 Yunier PÉREZ CUB 9.98 10.00 10.00 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 Bingtian SU CHN 9.99 9.99 10.09 SB 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 2017 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.82 +1.3 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 1 Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 25 9.90 +0.9 Yohan BLAKE JAM Kingston 23.06.17 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Ben Youssef MEITÉ (CIV) 24 9.92 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Pretoria 18.03.17 1. Usain BOLT (JAM) 9.81 3 Justin GATLIN (USA) 17 9.93 +0.8 Cameron BURRELL USA Eugene 07.06.17 2. -

A Comeback for Dawn Harper Nelson Delayed

Track & Field News January 2021 — 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume 74, No. 1 January 2021 From The Editor — What? There’s No 2020 World Rankings?! . 4 T&FN’s 2020 Podium Choices . 5 — T&FN’s 2020 World Men’s Track Podiums — . 6 — T&FN’s 2020 World Men’s Field Podiums — . 10 T&FN’S 2020 Men’s MVP — Mondo Duplantis . 15 Mondo Duplantis Figures He Still Has Many Years To Go . 16 — T&FN’s 2020 World Women’s Track Podiums — . 18 — T&FN’s 2020 World Women’s Field Podiums — . 22 T&FN’S 2020 Women’s MVP — Yulimar Rojas . 27 T&FN’s 2020 U .S . MVPs — Ryan Crouser & Shelby Houlihan . 28 Focus On The U .S . Women’s 100 Hurdles Scene . 29 Keni Harrison Looking For Championships Golds . 31 Brianna McNeal Ready To Defend Her Olympic Title . 33 A Comeback for Dawn Harper Nelson Delayed . 34 Sharika Nelvis Keeps On Moving Forward . 35 Christina Clemons Had A Long Road Back . 36 T&FN Interview — Grant Holloway . 37 Track News Digest . 41 Jenna Hutchins Emerges As The Fastest HS 5000 Runner Ever . 43 World Road Digest . 45 U .S . Road Digest . 46 Analysis: The Wavelight Effect . 47 Seb Coe’s Pandemic-Year Analysis . 51 STATUS QUO . 55 ON YOUR MARKS . 56 LAST LAP . 58 LANDMARKS . 61 FOR THE RECORD . 62 CALENDAR . 63 • cover photo of Mondo Duplantis by Jean-Pierre Durand • Track & Field News January 2021 — 3 FROM THE EDITOR Track & Field News The Bible Of The Sport Since 1948 — What? There’s No Founded by Bert & Cordner Nelson E. -

ATHLETES by EVENT and TEAM As of 4 September 2018 I = Indoor Performance

Ostrava (CZE) Continental Cup 8-9 September 2018 ATHLETES by EVENT and TEAM As of 4 September 2018 i = Indoor performance 78 329 MEN + WOMEN DATE of BIRTH Personal Best Season Best Qualification Best Countries Athletes 65 155 MEN Countries Athletes 8 8 100 Metres Countries Athletes AFR AFRICA Akani SIMBINE (RSA) 21 Sep 93 9.89 9.93 Arthur CISSÉ (CIV) 29 Dec 96 9.94 9.94 AME AMERICAS Yohan BLAKE (JAM) 26 Dec 89 9.69 9.94 Noah LYLES (USA) 18 Jul 97 9.88 9.88 APA ASIA-PACIFIC Bingtian SU (CHN) 29 Aug 89 9.91 9.91 Barakat AL HARTHI (OMA) 15 Jun 88 9.97 9.97 EUR EUROPE Jak Ali HARVEY (TUR) 4 May 89 9.92 9.99 Churandy MARTINA (NED) 3 Jul 84 9.91 10.16 8 8 200 Metres Countries Athletes AFR AFRICA Ncincihli TITI (RSA) 15 Dec 93 20.00 20.00 Ejowvokoghene ODUDURU (NGR) 7 Oct 96 20.13 20.13 AME AMERICAS Alonso EDWARD (PAN) 8 Dec 89 19.81 19.90 Alex QUIÑÓNEZ (ECU) 11 Aug 89 19.93 19.93 APA ASIA-PACIFIC Joseph MILLAR (NZL) 24 Sep 92 20.37 20.60 Yuki KOIKE (JPN) 13 May 95 20.23 20.23 EUR EUROPE Ramil GULIYEV (TUR) 29 May 90 19.76 19.76 Nethaneel MITCHELL-BLAKE (GBR) 2 Apr 94 19.95 20.04 8 8 400 Metres Countries Athletes AFR AFRICA Baboloki THEBE (BOT) 18 Mar 97 44.02 44.54 Thapelo PHORA (RSA) 21 Nov 91 45.35 45.35 AME AMERICAS Luguelín SANTOS (DOM) 12 Nov 92 44.11 44.59 Nathan STROTHER (USA) 6 Sep 95 44.34 44.34 APA ASIA-PACIFIC Muhammed Anas YAHIYA (IND) 17 Sep 94 45.24 45.24 Abdalelah HAROUN (QAT) 1 Jan 97 44.07 44.07 EUR EUROPE Kevin BORLÉE (BEL) 22 Feb 88 44.56 45.07 Matthew HUDSON-SMITH (GBR) 26 Oct 94 44.48 44.63 8 8 800 Metres Countries Athletes -

— World Relays #4 — Shadrick Tansi, Daniel Baul); 5

Volume 17, No. 28 May 12, 2019 4. Papua New Guinea 1:26.96 NR (Emmanuel Wanga, Nazmie-Lee Marai, — World Relays #4 — Shadrick Tansi, Daniel Baul); 5. Ecuador 1:27.22 NR (Carlos Perlaza, Jhon Valencia, Yokohama, Japan Jirka, Dominik Záleský); 6. Thailand Alex Quiñónez, David Cetre);… dq—France 38.82 (Ruttanapon Sowan, Nutthapong (Marvin René, Gautier Dautremer, Ryan Zeze, May 11–12 Veeravongratan, Jirapong Meenapra, Amaury Golitin) & Jamaica (Chadic Hinds, Siripol Punpa); 7. Ukraine 38.84 (Oleksandr Nigel Ellis, Oshane Bailey, Jevaughn Minzie). WORLD RELAYS MEN Sokolov, Emil Ibrahimov, Volodymyr Suprun, II–1. South Africa 1:20.64 NR (#5 (5/11—4x1h, 4x4h) Serhiy Smelyk);… dq—Zimbabwe (Dicksson nation) (Jon Seeliger, Anaso Jobodwana, Kamungeremu, Tatenda Tsumba, Itayi Dambile, Van Wyk); 4 x 100 Vambe, Ngoni Makusha). 2. Germany 1:21.63; 3. China 1:21.70; 1. Brazil 38.05 (WL) (Rodrigo Do III–1. United States 38.34 (AL) (Rodgers, 4. Nigeria 1:22.08 (Jakpa, Adegoke, Nascimento, Jorge Vides, Derick Silva, Gatlin, Young, Cameron Burrell); Ogho-Oghene Egwero, Arowolo); 5. Japan Paulo De Oliveira); 2. China 38.51; 1:23.15 (Miyamoto, Kirara Shiraishi, Tamura, 2. United States 38.07 (AL) (Mike 3. Canada 38.76 (Gavin Smellie, Aaron Fujimitsu); Rodgers, Justin Gatlin, Isiah Young, Noah Brown, Brendon Rodney, Andre De Grasse); … dnf—Brazil (Vítor Dos Santos, Jorge Lyles); 4. Chinese Taipei 38.89 (Tai-Sheng Wei, Wei- Vides, Derick Silva, Paulo De Oliveira). 3. Great Britain 38.15 (CJ Ujah, Harry Hsu Wang, Chun-Han Yang, Po-Yu Cheng); 4 x 400 Aikines-Aryeetey, Adam Gemili, Nethaneel 5. -

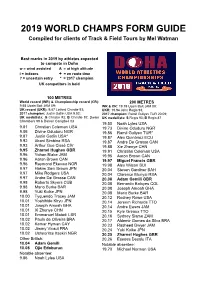

2019 WORLD CHAMPS FORM GUIDE Compiled for Clients of Track & Field Tours by Mel Watman

2019 WORLD CHAMPS FORM GUIDE Compiled for clients of Track & Field Tours by Mel Watman Best marks in 2019 by athletes expected to compete in Doha w = wind assisted A = at high altitude i = indoors + = e n route time ? = uncertain entry * = 2017 champion UK competitors in bold 100 METRES World record (WR ) & Championship record (C R): 200 METRES 9.5 8 Usain Bolt JAM 09 ; WR & CR: 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 09; UK record (UKR): 9.87 Linford Christie 93; UKR: 19.94 John Regis 93; 201 7 champion: Justin Gatlin USA 9.92 ; 201 7 champion: Ramil Guliyev TUR 20.09 ; UK medallists: G Christie 93; B Christie 87, Dwain UK medallists : S Regis 93; B Regis 87 Chambers 99 & Darren Campbell 03 19.50 Noah Lyles USA 9.8 1 Christian Coleman USA 19.7 3 Divine Oduduru NGR 9. 86 Divine Oduduru NGR 19.86 Ramil Guliyev TUR* 9.87 Justin Gatlin USA * 19.87 Alex Quinónez ECU 9.92 Akani Simbine RSA 19.87 Andre De Grasse CAN 9.93 Arthur Gue Cissé CIV 19.88 Xie Zhenye CHN 9.9 5 Zharnel Hughes GBR 19.91 Christian Coleman USA 9.96 Yohan Blake JAM 19.95 Aaron Brown CAN 9.96 Aaron Brown CAN 19.97 Miguel Francis GBR 9.96 Raymond Ekevwo NGR 19.98 Alex Wilson SUI 9.97 Hakim Sani Brown JPN 20.04 Steven Gardiner BAH 9.97 Mike Rodgers USA 20.04 Clarence Munyai RSA 9.97 Andre De Grasse CAN 20.08 Adam Gemili GBR 9.98 Roberto Skyers CUB 20.08 Bernardo Baloyes COL 9.98 Mario Burke BAR 20.08 Joseph Amoah GHA 9.98 Yuki Koike JPN 20.08 Mario Burke BAR 10.00 Tyquendo Tracey JAM 20.12 Rodney Rowe USA 10.01 Yoshihide Kiryu JPN 20.14 Jereem Richards TTO 10.01 Joseph Amoah GHA 20.14 Andre Ewers JAM 10.01 Xi Zhenye CHN 20.15 Kyle Greaux TTO 10.01 Emmanuel Matadi LBR 20.16 Sydney Siame ZAM 10.02 Paulo de Oliveira BRA 20.17 Aldemir Gomes da Silva BRA 10.02 Kemar Hyman CAY 20.23 Rasheed Dwyer JAM 10.02 Jimmy Vicaut FRA 20.24 Yuki Koike JPN 10.02 Usheoritse Itsekiri NGR 20.25 Zharnel Hughes GBR Other British: 20.26 Eseosa Desalu ITA 10.04 Adam Gemili Notable absentee : 10.08 Ojie Edoburun 19.70 Michael Norman USA Notable absentee: 9.86 Noah Lyles USA 400 METRES WR: 43. -

Shubenkov Dashes Merritt's Dreams Before Kidney OP

SPORTS SATURDAY, AUGUST 29, 2015 BEIJING: (L-R) Bahamas’s silver medallist Shaunae Miller, USA’s gold medallist Allyson Felix and Jamaica’s bronze medallist Shericka Jackson pose with their medals on the podium during the victory ceremony for the women’s 400 metres athletics event at the 2015 IAAF World Championships at the “Bird’s Nest” National Stadium in Beijing. (Centre) Men’s 200m gold medalist Jamaica’s Usain Bolt, centre, stands with silver medalist United States’ Justin Gatlin,left, and bronze medalist South Africa’s Anaso Jobodwana on the podium following the medal ceremony. (Right) Poland’s Maria Andrejczyk competes in women’s javelin throw qualification at the World Athletics Championships at the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing.— AFP/AP photos Bolt’s scooter assailant says sorry with bracelet BEIJING: The cameraman who sent Usain Bolt Jamaican from behind. returning to his duties at the Bird’s Nest stadium ring to the iconic venue for the 2008 Olympics. flying at the world athletics championships pre- Bolt, the six-times Olympic champion, in Beijing. The bizarre mishap is set to become Some Internet users remarked that the unlucky sented him with a red bracelet yesterday to escaped serious injury in the accident which an enduring image of the Beijing world champi- cameraman was the only man capable of taking apologise after footage of the incident went happened as he celebrated sealing the world onships after it trended on social media and fea- down Bolt, who has won all but one world and viral. A red-faced Song Tao of China’s CCTV sprint double with an emphatic 200m win on tured prominently in TV news bulletins. -

Men's 200M Final 14.08.2020

Men's 200m Final 14.08.2020 Start list 200m Time: 21:32 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Marvin RENÉ FRA 19.80 20.59 WR 19.19 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 20.08.09 2 Mouhamadou FALL FRA 19.80 20.34 21.81 AR 19.72 Pietro MENNEA ITA Ciudad de México 12.09.79 3 Mario BURKE BAR 19.97 20.08 NR 21.89 Sébastien GATTUSO MON Marsa 05.06.03 WJR 19.93 Usain BOLT JAM Hamilton 11.04.04 4 Josephus LYLES USA 19.32 20.24 20.24 MR 19.65 Noah LYLES USA 20.07.18 5 Adam GEMILI GBR 19.94 19.97 DLR 19.26 Yohan BLAKE JAM Boudewijnstadion, Bruxelles 16.09.11 6 Ramil GULIYEV TUR 19.76 19.76 SB 19.80 Kenneth BEDNAREK USA Montverde, FL 10.08.20 7 Noah LYLES USA 19.32 19.50 19.94 8 Deniz ALMAS GER 20.20 20.88 20.88 2020 World Outdoor list 19.80 +1.0 Kenneth BEDNAREK USA Montverde, FL (USA) 10.08.20 19.94 +0.8 Noah LYLES USA Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 Medal Winners Monaco previous 19.96 +1.0 Steven GARDINER BAH Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 20.22 +0.8 Divine ODUDURU NGR Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics Winners 20.23 +0.1 Clarence MUNYAI RSA Pretoria (RSA) 13.03.20 1. Noah LYLES (USA) 19.83 18 Noah LYLES (USA) 19.65 20.24 +0.8 André DE GRASSE CAN Clermont, FL (USA) 25.07.20 2. -

Provided by All-Athletics.Com Men's 100M

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 18.06.2017 Start list 100m Time: 17:40 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 2 Yunier PÉREZ CUB 9.98 10.10 10.10 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 3 Ben Youssef MEITÉ CIV 9.96 9.96 10.03 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 4 Andre DE GRASSE CAN 9.84 9.91 10.01 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 5 Alex WILSON SUI 10.11 10.11 10.11 NR 10.18 Peter KARLSSON SWE Cottbus 09.06.96 6 Churandy MARTINA NED 9.91 9.91 10.19 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene 13.06.14 MR 9.84 Tyson GAY USA 06.08.10 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 SB 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 Medal Winners Road To The Final 1 Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 17 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Chijindu UJAH (GBR) 13 2017 World Outdoor list 1. Usain BOLT (JAM) 9.81 3 Ben Youssef MEITÉ (CIV) 10 9.82 +1.3 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 2. Justin GATLIN (USA) 9.89 3 Ronnie BAKER (USA) 10 9.88 +0.2 Sydney SIAME ZAM Lusaka 08.04.17 3. Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 9.91 5 Justin GATLIN (USA) 9 9.92 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Pretoria 18.03.17 6 Akani SIMBINE (RSA) 8 2016 - Amsterdam European Ch. -

RESULTS 4 X 100 Metres Relay Men - Round 1 First 2 in Each Heat (Q) and the Next 2 Fastest (Q) Advance to the Final

Silesia (POL) 1-2 May 2021 RESULTS 4 x 100 Metres Relay Men - Round 1 First 2 in each heat (Q) and the next 2 fastest (q) advance to the Final RECORDS RESULT TEAM COUNTRY VENUE DATE World Record WR 36.84 Jamaica JAM Olympic Stadium, London (GBR) 11 Aug 2012 Championship Record CR 37.38 United States USA T. Robinson Stadium, Nassau (BAH) 2 May 2015 World Leading WL 38.29 PR of China CHN Shenzhen (CHN) 20 Mar 2021 Area Record AR National Record NR Season Best SB 1 May 2021 20:38 START TIME 10° C 85 % Heat 1 3 TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY PLACE TEAM BIB LANEREACTION RESULT Fn 1 NETHERLANDS NED 5 0.145 38.79 (.782) Q SB Joris VAN GOOL 10.74 (1) Taymir BURNET 9.27 (2) 20.01 (2) Christopher GARIA 9.42 (3) 29.43 (1) Churandy MARTINA 9.36 (2) 2 GHANA GHA 7 0.148 38.79 (.790) Q SB Sean SAFO-ANTWI 10.85 (5) Benjamin AZAMATI-KWAKU 9.10 (1) 19.95 (1) Joseph ODURO MANU 9.61 (4) 29.56 (2) Joseph Paul AMOAH 9.23 (1) 3 UKRAINE UKR 8 0.132 39.06 (.059) SB Erik KOSTRYTSYA 10.82 (4) Em іl IBRAHIMOV 9.51 (5) 20.33 (4) Stanislav KOVALENKO 9.37 (1) 29.70 (3) Serhiy SMELYK 9.36 (2) 4 SPAIN ESP 6 0.167 39.30 SB José GONZALEZ 10.94 (6) Pol RETAMAL 9.43 (4) 20.37 (5) Jesús GÓMEZ 9.40 (2) 29.77 (4) Sergio LÓPEZ 9.53 (4) 5 TURKEY TUR 3 0.161 39.59 SB Emre Zafer BARNES 10.74 (1) Jak Ali HARVEY 9.42 (3) 20.16 (3) Ertan ÖZKAN 9.85 (5) 30.01 (5) Ramil GULIYEV 9.58 (5) CZECH REPUBLIC CZE 4 0.149 DNF Zden ěk STROMŠÍK 10.74 (1) Ji ří POLÁK Jan JIRKA Jan VELEBA INTERMEDIATE TIMES 100m10.74 CZECH REPUBLIC 200m19.95 GHANA 300m29.43 NETHERLANDS 1 May 2021 20:47 START TIME 10° C 85 -

0 E Event TD

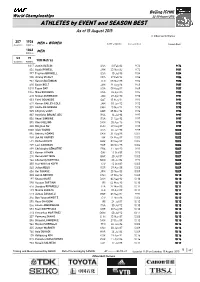

Beijing (CHN) World Championships 22-30 August 2015 ATHLETES by EVENT and SEASON BEST As of 15 August 2015 i = Indoor performance 207 1936 Countries Athletes MEN + WOMEN DATE of BIRTH Personal Best Season Best 1043 Athletes MEN 53 75 Countries Athletes 100 Metres 1017 Justin GATLIN USA10 Feb 82 9.749.74 634 Asafa POWELL JAM23 Nov 82 9.729.81 997 Trayvon BROMELL USA10 Jul 95 9.849.84 500 Jimmy VICAUT FRA27 Feb 92 9.869.86 937 Keston BLEDMAN TTO08 Mar 88 9.869.86 620 Usain BOLT JAM21 Aug 86 9.589.87 1018 Tyson GAY USA09 Aug 82 9.699.87 1054 Mike RODGERS USA24 Apr 85 9.859.88 618 Nickel ASHMEADE JAM07 Apr 90 9.909.91 831 Femi OGUNODE QAT15 May 91 9.919.91 619 Kemar BAILEY-COLE JAM10 Jan 92 9.929.92 309 Andre DE GRASSE CAN10 Nov 94 9.959.95 529 Chijindu UJAH GBR05 Mar 94 9.969.96 837 Henricho BRUINTJIES RSA16 Jul 93 9.979.97 856 Akani SIMBINE RSA21 Sep 93 9.979.97 895 Kim COLLINS SKN05 Apr 76 9.969.98 338 Bingtian SU CHN29 Aug 89 9.999.99 1068 Isiah YOUNG USA05 Jan 90 9.9910.00 894 Antoine ADAMS SKN31 Aug 88 10.0110.03 958 Jak Ali HARVEY TUR04 May 89 10.0310.03 527 Richard KILTY GBR02 Sep 89 10.0510.05 209 Levi CADOGAN BAR08 Nov 95 10.0610.06 499 Christophe LEMAITRE FRA11 Jun 90 9.9210.07 321 Kemar HYMAN CAY11 Oct 89 9.9510.07 210 Ramon GITTENS BAR20 Jul 87 10.0210.07 764 Churandy MARTINA NED03 Jul 84 9.9110.08 355 Hua Wilfried KOFFI CIV12 Oct 87 10.0510.09 548 Julian REUS GER29 Apr 88 10.0510.09 656 Kei TAKASE JPN25 Nov 88 10.0910.09 303 Aaron BROWN CAN27 May 92 10.0510.10 197 Shavez HART BAH06 Sep 92 10.1010.10 598 Hassan TAFTIAN IRI04 -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 30.06.2018

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 30.06.2018 Start list 100m Time: 21:52 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.98 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Yohan BLAKE JAM 9.58 9.69 10.00 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 3 Jimmy VICAUT FRA 9.86 9.86 9.92 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.0I.15 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 0I.06.16 4 Ronnie BAKER USA 9.69 9.90 9.90 NR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.0I.15 5 Michael RODGERS USA 9.69 9.85 9.89 NR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 0I.06.16 6 Bingtian SU CHN 9.91 9.91 9.91 WJR 9.9I Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 I Arthur CISSÉ CIV 9.94 9.94 9.94 MR 9.I9 Usain BOLT JAM 1I.0I.09 8 Jeff DEMPS USA 9.69 10.01 10.02 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 SB 9.88 Noah LYLES USA 22.06.18 Medal Winners Road To The Final 2018 World Outdoor list 1 Reece PRESCOD (GBR) 8 9.88 +1.1 Noah LYLES USA Des Moines, IA 22.06.18 2017 - London IAAF World Ch. in 1 Ronnie BAKER (USA) 8 9.89 +1.4 Michael RODGERS USA Des Moines, IA 21.06.18 Athletics 3 Jimmy VICAUT (FRA) I 9.90 +1.1 Ronnie BAKER USA Des Moines, IA 22.06.18 9.91 +0.4 Zharnel HUGHES GBR Kingston 09.06.18 1.