Formylglycine-Generating Enzyme Binds Substrate Directly at a Mononuclear Cu(I) Center to Initiate O2 Activation Mason J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Screening for Possible Novel

11 M060072591U NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY tilt• YUNIBESITI YA BOKONE•BOPHIRIMA NOOROVVE S-UNIVERSITEIT PHYLOGENETIC SCREENING FOR POSSIBLE NOVEL ANTIBIOTIC PRODUCING ACTINOMYCETES FROM RHIZOSPHERIC SOIL SAMPLES COLLECTED FROM NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA DISTRICT IN NORTH WEST PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA I BY MOBOLAJI FELICIA ADEGBOYE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (BIOLOGY) DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF SCIENCE, AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY, MAFIKENG CAMPUS SOUTH AFRICA Supervisor: Professor Olubukola 0. Babalola 2014 LIBRARY o MAFIKENG CAMPUS CALL NO.: 2021 -02- 0 4 DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis submitted to the North-West University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology in the Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Technology, School of Environmental and Health Sciences, and the work contained herein is my original work with exemption to the citations and that this work has not been submitted at any other University in partial or entirely for the award of any degree. Name: Mobolaji Felicia Adegboye Signature: .....~ •·· ··· ····· ·· .. ··············· ..... Date: .... ~S.. .. ....a~ ·1·· ·'.}Q~i; ... ............ .... DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Almighty God for His faithfulness over my life and for making my helpers to be many. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest thanks, gratitude and appreciation to my supervisor and mentor, Prof. Olubukola 0. Babalola for giving me the opportunity to pursue my doctoral degree under her supervision and for her encouragement, help and kind support. Her invaluable advice, suggestions, discussions and guidance were a real support to me. I acknowledge with honour and gratitude the International Foundation for Science (IFS) for research grant (F/5330-1 ), Connect Africa Scholarship Award, H3ABioNet/SANBio Scholarship and North-West University for offering me bursary/scholarship award to pursue the PhD degree. -

© 2016 Shiliang Tian

© 2016 Shiliang Tian PROTEIN ENGINEERING USING AZURIN AS THE SCAFFOLD: CAPTURING AND STUDYING NOVEL METAL-SULFENATE AND METAL-NO SPECIES BY SHILIANG TIAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Yi Lu, Chair Professor Thomas B. Rauchfuss Professor Wilfred A. van der Donk Assistant Professor Alison R. Fout Abstract Metalloproteins account for nearly half of all proteins in nature. Metal ions play important roles in catalyzing numerous important biological processes that necessary to sustain life on the planet, such as photosynthesis, respiration and nitrogen fixation. Much effort has been made to understand the relationship between structures and functions of metalloproteins. Although significant progresses have been made to obtain the knowledge of how metalloproteins work, the ultimate test is to use this knowledge to design new metallproteins that reproduce the structures and functions of native proteins. Protein redesign strategy is one of the most effective approaches in the design and engineering of artificial metalloenzymes. The advantage of a protein redesign strategy is that it can bypass the problem of developing a stable protein fold because many native proteins have remarkable adaptability for changes. The use of small, stable, easy-to- make, and well-characterized blue copper protein azurin as scaffold to design novel metal binding sites has been proven to be a promising way for protein redesign. Not only can its reduction potential be rationally tuned beyond the nature range via secondary coordination sphere engineering, but also the CuA and redox- active nonheme iron sites have been successfully engineered in azurin. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplemental Table 1. GO terms for the Flavonoid biosynthesis pathway and genes identified through pathway-level co-expression analysis. The ranking is sorted for descending counts within the pathway. The last two columns give the number of genes within or outside the pathway that are annotated with the term listed in the second column. GO id GO term Genes Genes within outside pathway pathway GO:0008372 cellular component unknown 13 28 GO:0016207 4-coumarate-CoA ligase activity 12 0 GO:0008152 metabolism 8 7 GO:0019350 teichoic acid biosynthesis 8 0 GO:0009234 menaquinone biosynthesis 8 0 GO:0009698 phenylpropanoid metabolism 7 0 GO:0009813 flavonoid biosynthesis 7 0 GO:0008299 isoprenoid biosynthesis 6 0 GO:0009507 chloroplast 5 24 GO:0009411 response to UV 4 0 GO:0016706 "oxidoreductase activity, acting on paired donors, with 4 0 incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen, 2- oxoglutarate as one donor, and incorporation of one atom each of oxygen into both donors" GO:0009058 biosynthesis 3 2 GO:0009699 phenylpropanoid biosynthesis 3 1 GO:0008415 acyltransferase activity 3 1 GO:0004315 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier protein] synthase activity 3 0 GO:0006633 fatty acid biosynthesis 3 0 GO:0005739 mitochondrion 2 7 GO:0005783 endoplasmic reticulum 2 1 GO:0009695 jasmonic acid biosynthesis 2 1 GO:0009611 response to wounding 2 1 GO:0005506 iron ion binding 2 1 GO:0016216 isopenicillin-N synthase activity 2 0 GO:0005777 peroxisome 2 0 GO:0045430 chalcone isomerase activity 2 0 GO:0009705 vacuolar membrane (sensu Magnoliophyta) 2 0 GO:0004321 -

Microorganisms: a Potential Source of Bioactive Molecules for Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Applications

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 4 January 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202101.0025.v1 Review Microorganisms: A Potential Source of Bioactive molecules for Antioxidants and Antimicrobial Applications Alka Rani 1#, Khem Chand Saini 1#, Felix Bast 1, Sanjeet Mehariya 2, Shashi Kant Bhatia 3, Roberto Lavecchia 2 and Antonio Zuorro 2,* 1 Department of Botany, School of Basic and Applied Sciences, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda, Pun- jab, India -151001; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (K.C.S.); [email protected] (F.B.) 2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Materials and Environment, Sapienza University of Rome, 00184 Rome, Italy; [email protected] (R.L.) 3 Department of Biological Engineering, College of Engineering, Konkuk University, Seoul 05029, Republic of Korea; [email protected] (S.K.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (A.Z.) Abstract: Oxidative stress is an elevated intracellular level of free oxygen radicals that cause lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, DNA hydroxylation, and apoptosis, ultimately negotiating cells viability. Antioxidants can scavenge such free radicals, thus reducing the oxidative stress and even- tually prevent cellular damage. Medicinal plants, fruits, and spices remain the prioritized sources of antioxidants and antimicrobial properties since the time immemorial, but in contrast to plants, mi- croorganisms can be grown at a faster rate under controlled conditions. They are non-toxic, non- carcinogenic, and biodegradable as compared to synthetic antioxidants. Microorganisms including actinomycetes, archaea, bacteria, protozoa, yeast, and fungi are auspicious source of vital bioactive compounds. The list comprises ample of bioactive components from microorganisms. -

Role of Rim101p in the Ph Response in Candida Albicans Michael Weyler

Role of Rim101p in the pH response in Candida albicans Michael Weyler To cite this version: Michael Weyler. Role of Rim101p in the pH response in Candida albicans. Biomolecules [q-bio.BM]. Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2007. English. tel-00165802 HAL Id: tel-00165802 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00165802 Submitted on 27 Jul 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE PARISXI UFR SCIENTIFIQUE D’ORSAY THESE présentée par Michael Weyler pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR EN SCIENCES DE L’UNIVERSITE PARISXI-ORSAY LE RÔLE DE RIM101p DANS LA RÉPONSE AU pH CHEZ CANDIDA ALBICANS Soutenance prévue le 6 juillet 2007 devant le jury composé de: Pr. Dr. H. Delacroix Président Dr. J-M. Camadro Rapporteur Pr. Dr. F. M. Klis Rapporteur Dr. G. Janbon Examinateur Dr. M. Lavie-Richard Examinateur Pr. Dr. C. Gaillardin Examinateur Remerciements Tout d’abord je voudrais remercier vivement mon directeur de thèse, Prof. Claude Gaillardin, pour m’avoir permis d’effectuer ce travail au sein de son laboratoire, pour ses conseils et sa disponibilité malgré son calendrier bien remplis. Je lui remercie également pour m’avoir laissé beaucoup de liberté dans mon travail, et pour la possibilité de participer aux différents congrès au cours de ma formation de thèse. -

Mechanistic Study of Cysteine Dioxygenase, a Non-Heme

MECHANISTIC STUDY OF CYSTEINE DIOXYGENASE, A NON-HEME MONONUCLEAR IRON ENZYME by WEI LI Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2014 Copyright © by Student Name Wei Li All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Pierce for your mentoring, guidance and patience over the five years. I cannot go all the way through this without your help. Your intelligence and determination has been and will always be an example for me. I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Dias, Dr. Heo and Dr. Jonhson- Winters for the directions and invaluable advice. I also would like to thank all my lab mates, Josh, Bishnu ,Andra, Priyanka, Eleanor, you all helped me so I could finish my projects. I would like to thank the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry for the help with my academic and career. At Last, I would like to thank my lovely wife and beautiful daughter who made my life meaningful and full of joy. July 11, 2014 iii Abstract MECHANISTIC STUDY OF CYSTEINE DIOXYGENASE A NON-HEME MONONUCLEAR IRON ENZYME Wei Li, PhD The University of Texas at Arlington, 2014 Supervising Professor: Brad Pierce Cysteine dioxygenase (CDO) is an non-heme mononuclear iron enzymes that catalyzes the O2-dependent oxidation of L-cysteine (Cys) to produce cysteine sulfinic acid (CSA). CDO controls cysteine levels in cells and is a potential drug target for some diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzhermer’s. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Zheng Zhao, Delft University of Technology Marcel A. van den Broek, Delft University of Technology S. Aljoscha Wahl, Delft University of Technology Wilbert H. Heijne, DSM Biotechnology Center Roel A. Bovenberg, DSM Biotechnology Center Joseph J. Heijnen, Delft University of Technology An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Marco A. van den Berg, DSM Biotechnology Center Peter J.T. Verheijen, Delft University of Technology Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. PchrCyc: Penicillium rubens Wisconsin 54-1255 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Liang Wu, DSM Biotechnology Center Walter M. van Gulik, Delft University of Technology L-quinate phosphate a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar multidrug multidrug a dicarboxylate phosphate a proteinogenic 2+ 2+ + met met nicotinate Mg Mg a cation a cation K + L-fucose L-fucose L-quinate L-quinate L-quinate ammonium UDP ammonium ammonium H O pro met amino acid a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar a sugar K oxaloacetate L-carnitine L-carnitine L-carnitine 2 phosphate quinic acid brain-specific hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical hypothetical -

The Bioinorganic Chemistry of Copper-Containing Systems: from Type-3 Systems Pertinent to Alzheimer's Disease to Mononuclear H

The Bioinorganic Chemistry Of Copper-Containing Systems: From Type-3 Systems Pertinent To Alzheimer’s Disease To Mononuclear Hydrolysis Involved In Biological Development by Giordano Faustini Zimmerer Da Silva A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Chemistry College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Li-June Ming, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Brian T. Livingston, Ph.D. Steven H. Grossman, Ph.D. Randy L. Larsen, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 9, 2007 Keywords: kinetics, reactive oxygen species, metallopeptide, amyloid, enzymology, sea urchin, metalloprotease © Copyright 2007 , Giordano F.Z. Da Silva NOTE TO THE READER Note to Reader: The original of this document contains color that is necessary for understanding the data. The original dissertation is on file at the USF library in Tampa, FL. DEDICATION Although the graduate school experience is highly a personal journey, it would be foolish to believe that I was solely responsible for my accomplishments. I then would like to dedicate this work to all of those who have played a major role in this difficult yet rewarding part of my life. First my grandmother Ermelinda who is the sole reason why I am in the US, my parents Mauricio and Marta for sacrificing the presence of their son, and my sister Marcella for being sibling, friend and parent through part of my formative years. Second I must dedicate this work to the Kelley family for being my parents, brother, and sisters; Moms, Pops, John, Tere, and Abbie, I would not be here today without your love and support. -

12) United States Patent (10

US007635572B2 (12) UnitedO States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,635,572 B2 Zhou et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 22, 2009 (54) METHODS FOR CONDUCTING ASSAYS FOR 5,506,121 A 4/1996 Skerra et al. ENZYME ACTIVITY ON PROTEIN 5,510,270 A 4/1996 Fodor et al. MICROARRAYS 5,512,492 A 4/1996 Herron et al. 5,516,635 A 5/1996 Ekins et al. (75) Inventors: Fang X. Zhou, New Haven, CT (US); 5,532,128 A 7/1996 Eggers Barry Schweitzer, Cheshire, CT (US) 5,538,897 A 7/1996 Yates, III et al. s s 5,541,070 A 7/1996 Kauvar (73) Assignee: Life Technologies Corporation, .. S.E. al Carlsbad, CA (US) 5,585,069 A 12/1996 Zanzucchi et al. 5,585,639 A 12/1996 Dorsel et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,593,838 A 1/1997 Zanzucchi et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,620,850 A 4/1997 Bamdad et al. 5,624,711 A 4/1997 Sundberg et al. (21) Appl. No.: 10/865,431 5,627,369 A 5/1997 Vestal et al. 5,629,213 A 5/1997 Kornguth et al. (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2005/O118665 A1 Jun. 2, 2005 EP 596421 10, 1993 EP 0619321 12/1994 (51) Int. Cl. EP O664452 7, 1995 CI2O 1/50 (2006.01) EP O818467 1, 1998 (52) U.S. -

Supplementary Figure 1. Rpod Sequence Alignment. Protein Sequence Alignment Was Performed for Rpod from Three Species, Pseudoruegeria Sp

J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1911.11006 J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2003.03025 Supplementary Figure 1. RpoD sequence alignment. Protein sequence alignment was performed for RpoD from three species, Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M (FPS10_24745, this study), Ruegeria pomeroyi (NCBI RefSeq: WP_011047484.1), and Escherichia coli (NCBI RefSeq: NP_417539.1). Multalin version 5.4.1 was used for the analysis. Subregion 2 and 4 are represented in a rectangle, and the helix-turn-helix motif in subregion 4 is highlighted in red. The amino acid degeneration from any of the three was highlighted in light gray and the sequence degeneration between Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M and R. pomeroyi is highlighted in dark gray. The substituted two amino acids into HTH motif (K578Q and D581S) against E. coli were marked as asterisk. Supplementary Table 1. Genome assembly statistics Categories Pseudoruegeria sp. M32A2M Number of scaffolds less than 1,000 bp 0 Number of scaffolds between 1,000 bp –10,000 bp 39 Number of scaffolds between 10,000 bp – 100,000 bp 38 Number of scaffolds larger than 100,000 bp 14 Number of scaffolds 91 Total assembled length (bp) 5,466,515 G+C contents (%) 62.4 N50 (bp) 249,384 Minimum length of scaffold (bp) 1,015 Maximum length of scaffold (bp) 733,566 Total Ns included in the draft genome 2,158 Supplementary Table 2. The list of gene annotation and its functional categorization in Pseudoruegeria sp. -

Biochemical, Kinetic and Spectroscopic Characterizations Of

BIOCHEMICAL, KINETIC AND SPECTROSCOPIC CHARACTERIZATIONS OF NON-HEME IRON OXYGENASE ENZYMES by BISHNU P SUBEDI Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Science The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Bishnu P Subedi 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my greatest appreciation and thanks to my advisor Professor Brad S Pierce for giving me the opportunity to work in his lab and providing valuable guidance and encouragement during the research period. I would also like to thank Professor Frank W Foss both for being a member in my thesis committee and a collaborator on MiaE project. My sincerest thanks goes to Professor Frederick MacDonnell for his valuable suggestions as a chair in my thesis committee. I also thank the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at The University of Texas at Arlington for supporting my graduate study, the UTA Shimadzu Center for Advanced Analytical Chemistry for the use of HPLC and LC-MS/MS instrumentation utilized in this work, and the UTA Center for Nanostructured Materials for the use of EPR facilities. I would also like to thank Professor Paul Lindahl and Dr. Mrinmoy Chakrabarti, Texas A&M University for their generous assistance in collecting Mössbauer spectra for MiaE, similarly Professor Brian Fox and Justin Acheson, University of Wisconsin, Madison for collaboration on MiaE structural study and Professor Tim Larson, Virginia Tech Department of Biochemistry for the IPTG inducible Azotobacter vinelandii CDO expression vector. -

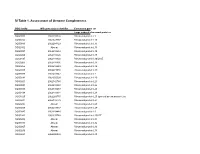

SI Table 1. Assessment of Genome Completeness

SI Table 1. Assessment of Genome Completeness COG family IMG gene object identifier Conserved gene set Large subunit ribosomal proteins COG0081 2062288324 Ribosomal protein L1 COG0244 2062347387 Ribosomal protein L10 COG0080 2062288323 Ribosomal protein L11 COG0102 Absent Ribosomal protein L13 COG0093 2062418832 Ribosomal protein L14 COG0200 2062418826 Ribosomal protein L15 COG0197 2062418838 Ribosomal protein L16/L10E COG0203 2062418836 Ribosomal protein L17 COG0256 2062418829 Ribosomal protein L18 COG0335 2062273558 Ribosomal protein L19 COG0090 2062418842 Ribosomal protein L2 COG0292 2062350539 Ribosomal protein L20 COG0261 2062142780 Ribosomal protein L21 COG0091 2062418840 Ribosomal protein L22 COG0089 2062138283 Ribosomal protein L23 COG0198 2062418834 Ribosomal protein L24 COG1825 2062269715 Ribosomal protein L25 (general stress protein Ctc) COG0211 2062142779 Ribosomal protein L27 COG0227 Absent Ribosomal protein L28 COG0255 2062418837 Ribosomal protein L29 COG0087 2062154483 Ribosomal protein L3 COG1841 2062335748 Ribosomal protein L30/L7E COG0254 Absent Ribosomal protein L31 COG0333 Absent Ribosomal protein L32 COG0267 Absent Ribosomal protein L33 COG0230 Absent Ribosomal protein L34 COG0291 2062350538 Ribosomal protein L35 COG0257 Absent Ribosomal protein L36 COG0088 2062138282 Ribosomal protein L4 COG0094 2062418833 Ribosomal protein L5 COG0097 2062418830 Ribosomal protein L6P/L9E COG0222 2062288326 Ribosomal protein L7/L12 COG0359 2062209880 Ribosomal protein L9 Small subunit ribosomal proteins COG0539 Absent Ribosomal protein