Innovative Learning Environments (ILE)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOES WHERE JESUS GOES Disciple – Part 1 Pastor Keith Stewart August 2, 2020

2660 Belt Line Road Garland, TX 75044 972.494.5683 www.springcreekchurch.org GOES WHERE JESUS GOES Disciple – Part 1 Pastor Keith Stewart August 2, 2020 Mimeithai means to imitate or mimic something. Tupos means pattern, example, or model. You became imitators (mimeithai) of us and of the Lord; in spite of severe suffering, you welcomed the message with the joy given by the Holy Spirit. 1 Thessalonians 1.6 Follow my example (mimeithai), as I follow the example of Christ. 1 Corinthians 11.1 We did this, not because we do not have the right to such help, but in order to offer ourselves as a model (tupos) for you to imitate. 1 Thessalonians 3.9 It’s like we’re looking for something that we’ve lost. 2660 Belt Line Road Garland, TX 75044 972.494.5683 www.springcreekchurch.org God knew what He was doing from the very beginning. He decided from the outset to shape the lives of those who love him along the same lines as the life of his Son. The Son stands first in the line of humanity He restored. We see the original and intended shape of our lives there in Him. After God made that decision of what His children should be like, He followed it up by calling people by name. After He called them by name, He set them on a solid basis with Himself. And then, after getting them established, He stayed with them to the end, gloriously completing what He had begun. Romans 8.29-30 (Message) “Christianity is making humanity what it ought to be.” – Leroy Forlines 1. -

Technology and Jewish Life1,2 Manfred Gerstenfeld and Avraham Wyler

www.jcpa.org Published March 2006 Jewish Political Studies Review 18:1-2 (Spring 2006) Technology and Jewish Life1,2 Manfred Gerstenfeld and Avraham Wyler Technology continues to have a strong and specific impact on Jewish life. It has caused major social changes in various areas, such as the suburbanization of Jews, women's increased learning, and the possibility of participating in worldwide community activities. From a socio-halakhic viewpoint, technology influences Jews' choice of residence, has socialized and politicized kashrut certification, and has changed modes of Jewish study. The development of new technologies has brought with it many halakhic challenges and decisions, on Shabbat observance among other things. Technology may also stimulate better observance of the commandments. It influences Jewish thinking and is leading to new ways of presenting ancient concepts. From a philosophical viewpoint, Judaism proposes a way of life that is not subordinated to technology, unlike life in general society. This is mainly expressed in the domain of holiness. Developing a more detailed analysis of the interaction between technology and Jewish life will open new horizons for learning, studying, thinking, research, determining halakha, and making practical decisions. Introduction The concept that technology is double-faced, that is, its use can make human life better or facilitate greater evil, can already be found in the midrashic literature on the first chapters of Genesis. The number of interactions between Jewish life and technology is far too large to be systematically enumerated. One can only outline how diverse this interaction is, and show that it goes much further than its most- discussed element: the impact of new technology on observance of the Torah and mitzvot (commandments). -

Rabbinic Biblical Exegesis and Its Importance for Christians and Jewish-Christian Relations

Rabbinic Biblical Exegesis and its importance for Christians and Jewish-Christian Relations David Rosen The destruction of the first Temple by the Babylonians in the year 586 BCE and the subsequent captivity, confronted the exiles with a literally existential crisis. The challenge was compounded by the fact that the northern kingdom of Israel had been overrun a century and a half earlier, its people exiled and ultimately lost (the “ten lost tribes”) to their brethren in Judea. The crisis/challenge for the exiles in Babylon was thus how to maintain their identity (in the hope of their eventual return to Judea) while in “an alien land “(see Psalm 137:4) While we do not have precise data in this regard, we can glean significant insights from the prophet Ezekiel who reports on gatherings of elders in his home where they set in motion what may be described as the very “secret” of Jewish survival. No longer could the people rely on the priestly leadership in the absence of the central religious shrine and its unifying order of service. Away from the land and without its national institutions, it was essential to ensure that the people became the personal possessors of religious knowledge – the religious history and the way of life that the Jewish people believed had been Divinely revealed to them. From the book of Ezekiel and other sources it appears that the synagogue emerged in the Babylonian exile as a place of congregation (as its name suggests) where the Judean exiles not only socialized and prayed for their return to Zion and its restoration, but above all where they received religious instruction (the meaning of the Hebrew word Torah) from priests and elders, setting in motion the meritocratic educational revolution that reached a zenith in the Talmudic period and which guaranteed Jewish posterity . -

Idea and Constraint in Americanjewish Education 73

d stable nature - producing knowl lroUghout, he points out various 'Vation. ted States in the world Jewish edu :tached academic perspective, we 3 tors who are actively working with tutional perspectives, and as indi Strangers to the Tradition: ;entations. The first is by Shimon the Jewish Education Service of Idea and Constraint non-denominational educational in AmericanJewish Education merica. The second is by Alvin .nsh Education of New York City, Walter I. Ackerman ~ystem in the Diaspora. The third :sociate Professor of Education in In, Hebrew Union College-Jewish The first Jewish school in the United States of which we know was :anada. Jerome Kutnick, Assistant founded in New York City in 1731, seventy-seven years after the arrival of lOUght at Gratz College, Philadel- the first group of 24 Jews in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, and one Canadian Jewish educational sys year after the Portuguese Jewish congregation, Shearith Israel, had completed ; the United States, both through construction of the first synagogue building in that city. The minutes of the ugh cultural influences. Yet, Can congregation noted that: :ttional structure and issues. There On the 21 st of Nissan, the 7th day of Pesach, the day of completing the 1 provinces with regard to Jewish first year of the opening ofthe synagogue, there was made codez (conse :-ound and government support of crated) the Yeshibat called Minchat Arab...for the use ofthis congrega ~s the opportunities and problems tion Shearith Israel and as a Beth Midrash for the pupils... (Dushkin, -

A History of Beth Jacob V'anshe Drildz by Howard Markus

A History of Beth Jacob V’Anshe Drildz by Howard Markus Assistant Archivist, Ontario Jewish Archives The first Jewish immigrants arrived in Toronto 1905 a building at 17 Elm Street was in the 1830s. By 1850, there were about 50 purchased and renovated for use as a Jews living in Toronto and by 1880 the Jewish synagogue. population had reached about 500. A majority of the early Jewish settlers had emigrated from In 1915 the congregation was instrumental in either Germany or England. They were founding a talmud torah. Initially, the classes merchants or professionals and many of them were held in the Beth Midrash of the Beth established their businesses along King Street Jacob synagogue. Shortly thereafter, the and Yonge Street. The Jewish residential area school moved to a house on Chestnut Street was at first in the Richmond and York area and afterwards to a house on Simcoe Street. and later in the Wellesley and Jarvis area. This talmud torah eventually became known as the Eitz Chaim Talmud Torah and a After the 1880s, the pattern of Jewish building on D’Arcy Street was purchased immigration changed. With the increase in several years later. anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire, there was a dramatic increase By 1915, the Jewish residential area had in the number of Jewish immigrants from shifted westwards and the majority of Jews those areas. By 1890, the Jewish population of now lived between University Avenue and Toronto had jumped to 1,500 and at the turn of Bathurst Street. A decision was made to move the century there were 3,000 Jews living in to a site west of University Avenue and in Toronto. -

The National-Cultural Movement in Hebrew Education in the Mississippi Valley

www.jcpa.org Jewish Community Studies The National-Cultural Movement in Hebrew Education in the Mississippi Valley Daniel J. Elazar The arrival of the mass migration of Eastern European Jews on American shores in the 1880s coincided with the heyday of the idea of the Mississippi Valley as an integral region -- the very heartland of the United States, the "real America" and the definer of the American spirit and way of life. The Mississippi Valley was a product of the nineteenth century. Even the eastern fringes of the vast territory from the Appalachians to the Rockies had hardly emerged from its frontier stage by 1880. The middle portions were principally populated by the sons and daughters of the pioneers and the region's western third was still being settled. Jews had settled in the eastern half of the region during its first generation of settlement and were among the first settlers of the western half. Hence, though the region's Jewish population represented only 20 percent of American Jewry and, with the exception of a few major cities, was to remain relatively small even after the great migration, it did contain hundreds of thousands of Jews. Those Jews Americanized quickly throughout most of the region. In some places, like New Orleans, successive communities assimilated almost entirely. In others, like St. Paul, Jews remained separate yet integrated into the best clubs (Plaut 1959). In some, like Chicago, they went through the complete urban immigrant experience of the kind that has become the basic stereotype of American Jewish folklore. In some, like Denver, they were among the very first pioneers, yet at the same time some of them actually reproduced an American version of an Eastern European shtetl, complete with cows, goats and truck gardens. -

2015 Hamerkaz

Fall 2015 Edition Happy New Year 5776 HA PUBLICATIONAMERKAZ OF THE SEPHARDIC EDUCATIONAL CENTER BOARD MEMBERS Dr. Jose A. Nessim, (z”l) Founder Executive Board: Neil J. Sheff, Chair Sarita Hasson Fields MESSAGE Freda Nessim Ronald J. Nessim FROM THE Steven Nessim Ray Mallel INTERNATIONAL Nira Sayegh DIRECTOR RABBI DANIEL BOUSKILA Yosi Avrahamy Joe Block Patrick Chirqui Brigitte Dayan Isack Fadlon OUR MISSION STATEMENT Lela Franco This past June, just a few days before flying to Israel for the summer, I was going Abe Mathalon through some files and I came across a copy of our SEC Mission Statement. Ditza Meles Edward Sabin I looked at it carefully, as I was now about to embark on a summer in Israel Limore Shalom that would hopefully fulfill the ideas and values expressed in these words. The Nir Weinblut Tamir Wertheim Hamsa Israel teen group’s itinerary was complete, as was the schedule of classes and lectures for the Metivta Rabbinic Seminar. I knew exactly which kids Rabbi Bouskila, SEC Director email: [email protected] were coming on Hamsa, and which rabbis were coming to study on Metivta. The challenge was to now present our participants – teenagers or rabbis – with World Executive Offices programs whose content and spirit matched the SEC’s vision of Judaism, as 6505 Wilshire Blvd • Suite 320 expressed in our Mission Statement. Much like we are encouraged to pray and Los Angeles, CA 90048 study Torah with kavanna (focus and concentration), I found myself reading the phone: 323.272.4574 fax: 323.576.5355 email: [email protected] following words with kavanna: SEC Jerusalem Campus Israel Shalem, Manager The SEC is dedicated to strengthening Jewish identity for youth and young adults, and to building a new generation of spiritual and community leaders. -

A Lively Community: the Liberal Jewish Community of Amsterdam

A Lively Community: The Liberal Jewish Community of Amsterdam Clary Rooda The Rappaport Center for Assimilation Research and Strengthening Jewish Vitality Bar Ilan University - Faculty of Jewish Studies 2007 - 5767 פרסום מסß 4 בסדרה מחקרי שדה של מרכז רפפורט לחקר ההתבוללות ולחיזוק החיוניות היהודית עורך הסדרה: צבי זוהר #4 in the series Field Reports of the Rappaport Center Series Editor: Zvi Zohar © כל הזכויות שמורות למחברת ולמרכז רפפורט לחקר ההתבוללות ולחיזוק החיוניות היהודית הפקולטה למדעי היהדות, אוניברסיטת בר–אילן, רמת–גן עריכה: דניס לוין הבאה לדפוס: איריס אהרן עיצוב עטיפה: סטודיו בן גסנר, ירושלים סודר ונדפס בדפוס "ארט פלוס", ירושלים התשס“ז Editor: Denise Levin Proofreading: Iris Aaron Cover: Ben Gasner Studio, Jerusalem Printed by “Art Plus”, Jerusalem © All rights reserved to the author and The Rappaport Center for Assimilation Research and Strengthening Jewish Vitality The Faculty of Jewish Studies Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel 2007 e-mail: [email protected] Preface The Rappaport Center for Assimilation Research and Strengthening Jewish Vitality is an independent R & D center, founded in Bar-Ilan University in the spring of 2001 at the initiative of Ruth and Baruch Rappaport, who identified assimilation as the primary danger to the future of the Jewish people. A central working hypothesis of the Center is that assimilation is not an inexorable force of nature, but the result of human choices. In the past, Jews chose assimilation in order to avoid persecution and social stigmatization. Today, however, this is rarely the case. In our times, assimilation stems from the fact that for many Jews, maintaining Jewish involvements and affiliations seems less attractive than pursuing the alternatives open to them in the pluralistic societies of contemporary Europe and America. -

064. Gafni, 225-265

SEVEN The World of the Talmud: From the Mishnah to the Arab Conquest ISAIAH M. GAFNI 0 SOME EXTENT, THE FOUR CENTURIES OF JEWISH HISTORY surveyed in this chapter-from the completion of the T Mishnah (c. 220 C.E.) to the Arab conquest of the East (early seventh century)-represent a continuation of the post-Bar Kokhba period. No longer do we encounter major political or mili tary opposition to the empires that ruled over those lands where the vast majority ofJews lived-whether in Palestine or the Diaspora. While the yearning for messianic redemption still asserts itself at certain major junctures, this messianism evinces itself in a far more spiritualized way (as it did in the previous period when the Mishnah was produced), rather than being centered around an other Bar-Kokhba-like Jewish military figure. Indeed, these messi anic passions henceforth arise primarily as a Jewish reaction to events totally beyond the control of the Jewish community itself whether it be the pagan-Christian clash in the days of the Roman emperor Julian (361-363 C.E.) that almost led to the restoration of Jewish Jerusalem, or the three-way struggle for control over the Land of Israel (Byzantium-Persia-Arabia) that paved the way for the Muslim conquest. More radical in its ultimate consequences is the slow but con stant shift in the delicate relationship between the Jewish center in Palestine and the emerging Jewish community of Babylonia. While 226 Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism A PAGE FROM THE TALMUD. The Talmud (Hebrew for instruction) is an authoritative collection of rabbinic commentary that includes the Mishnah (a collection of Jewish laws compiled by Judah ha-Nasi at the beginning of the third century C.E.) and the Gemara (an elabora tion and commentary on the Mishnah). -

Massachusetts Synagogues and Their Records, Past and Present by Carol Clingan

Massachusetts Synagogues and Their Records, Past and Present by Carol Clingan This listing attempts to identify and trace every synagogue that has been recorded in Massachusetts. All the information is accurate to the best that could be determined, but there are undoubtedly errors and omissions. Sources consulted include: city directories, real estate records incorporation papers, newspapers, and information from individual synagogues and their members. Wherever possible, name changes, location changes and mergers are recorded, as well as dates for the closing or disappearance of congregations. The symbol < before a date indicates that it is the earliest record found, while the symbol > indicates that it is the latest record found. In both cases, the actual date may be earlier or later. If a congregation is associated with a particular cemetery, there is a number that indicates the listing for that cemetery on the accompanying cemetery list. Records marked are to be found in the particular synagogue, but there are also other repositories listed in the column for “Other Records”. Here are the codes: AJHS American Jewish Historical Society (www.ajhs.org) JCAM Jewish Cemetery Association of Massachusetts (www.jcam.org) MA Massachusetts State Archives (www.sec.state.ma.us/arc) NEHA New England Hebrew Academy (www.theneha.org) NSJHS North Shore Jewish Genealogical Society (www.jhsns.net) Dartmouth Jewish Collection at University of Mass. Dartmouth library (www.lib.umassd.edu/archives/cjc-mc8.html) WHM Worcester Historical Society (www.worcesterhistory.org/founding.html) Copyright © 2010. Jewish Genealogical Society of Greater Boston, Inc. Contact [email protected] for permission to reproduce. CIC 7/6/10 (Rev. -

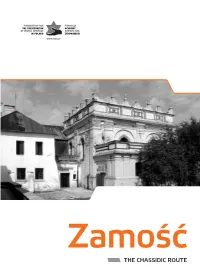

Chassidic-Route.Pdf

Zamość THE CHASSIDIC ROUTE 02 | Zamość | introduction | 03 Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was established in March ���� by the Dear Sirs, Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). �is publication is dedicated to the history of the Jewish community of Zamość and is a part Our mission is to protect and commemorate the surviving monuments of Jewish cultural of a series of pamphlets presenting history of Jews in the localities participating in the Chassidic heritage in Poland. �e priority of our Foundation is the protection of the Jewish cemeteries: in Route project, run by the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland since ����. cooperation with other organizations and private donors we saved from destruction, fenced and �e Chassidic Route is a tourist route which follows the traces of Jews from southeastern Poland commemorated several of them (e.g. in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Kłodzko, Iwaniska, and, soon, from western Ukraine. �� communities, which have already joined the project and where Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazowieckie). �e actions of our Foundation cover the priceless traces of the centuries-old Jewish presence have survived, are: Baligród, Biłgoraj, also the revitalization of particularly important and valuable landmarks of Jewish heritage, e.g. the Chełm, Cieszanów, Dębica, Dynów, Jarosław, Kraśnik, Lesko, Leżajsk (Lizhensk), Lublin, Przemyśl, synagogues in Zamość, Rymanów and Kraśnik. Ropczyce, Rymanów, Sanok, Tarnobrzeg, Ustrzyki Dolne, Wielkie Oczy, Włodawa and Zamość. We do not limit our heritage preservation activities only to the protection of objects. It is equally �e Chassidic Route runs through picturesque areas of southeastern Poland, like the Roztocze Hills important for us to broaden the public’s knowledge about the history of Jews who for centuries and the Bieszczady Mountains, and joins localities, where one can find imposing synagogues and contributed to cultural heritage of Poland. -

Halakhah of Jesus of Nazareth According to the Gospel of Matthew Studies in Biblical Literature

THE HALAKHAH OF JESUS OF NAZARETH ACCORDING TO THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW Studies in Biblical Literature Number 18 The Halakhah of Jesus of Nazareth according to the Gospel of Matthew THE HALAKHAH OF JESUS OF NAZARETH ACCORDING TO THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW by Phillip Sigal Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta THE HALAKHAH OF JESUS OF NAZARETH ACCORDING TO THE GOSPEL OF MATTHEW Copyright © 2007 by Lillian Sigal All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sigal, Phillip. The halakhah of Jesus of Nazareth according to the Gospel of Matthew / by Phillip Sigal. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature studies in biblical literature ; no. 18) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN: 978-1-58983-282-4 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. BJesus Christ—Teachings. 2. Divorce—Biblical teaching. 3. Sabbath—Biblical teaching. 4. Bible. N.T. Matthew—Criticism, interpretation, etc. 5. Jewish law. 6. Jesus Christ—Views on Jewish law. I. Title. BS2415.S55 2007b 226.2'06—dc22 2007020485 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence.