The Glib/GTK+ Development Platform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glibc and System Calls Documentation Release 1.0

Glibc and System Calls Documentation Release 1.0 Rishi Agrawal <[email protected]> Dec 28, 2017 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Acknowledgements...........................................1 2 Basics of a Linux System 3 2.1 Introduction...............................................3 2.2 Programs and Compilation........................................3 2.3 Libraries.................................................7 2.4 System Calls...............................................7 2.5 Kernel.................................................. 10 2.6 Conclusion................................................ 10 2.7 References................................................ 11 3 Working with glibc 13 3.1 Introduction............................................... 13 3.2 Why this chapter............................................. 13 3.3 What is glibc .............................................. 13 3.4 Download and extract glibc ...................................... 14 3.5 Walkthrough glibc ........................................... 14 3.6 Reading some functions of glibc ................................... 17 3.7 Compiling and installing glibc .................................... 18 3.8 Using new glibc ............................................ 21 3.9 Conclusion................................................ 23 4 System Calls On x86_64 from User Space 25 4.1 Setting Up Arguements......................................... 25 4.2 Calling the System Call......................................... 27 4.3 Retrieving the Return Value...................................... -

Preview Objective-C Tutorial (PDF Version)

Objective-C Objective-C About the Tutorial Objective-C is a general-purpose, object-oriented programming language that adds Smalltalk-style messaging to the C programming language. This is the main programming language used by Apple for the OS X and iOS operating systems and their respective APIs, Cocoa and Cocoa Touch. This reference will take you through simple and practical approach while learning Objective-C Programming language. Audience This reference has been prepared for the beginners to help them understand basic to advanced concepts related to Objective-C Programming languages. Prerequisites Before you start doing practice with various types of examples given in this reference, I'm making an assumption that you are already aware about what is a computer program, and what is a computer programming language? Copyright & Disclaimer © Copyright 2015 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book can retain a copy for future reference but commercial use of this data is not allowed. Distribution or republishing any content or a part of the content of this e-book in any manner is also not allowed without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. If you discover any errors on our website or in this tutorial, please notify us at [email protected] ii Objective-C Table of Contents About the Tutorial .................................................................................................................................. -

Source Code Trees in the VALLEY of THE

PROGRAMMING GNOME Source code trees IN THE VALLEY OF THE CODETHORSTEN FISCHER So you’ve just like the one in Listing 1. Not too complex, eh? written yet another Unfortunately, creating a Makefile isn’t always the terrific GNOME best solution, as assumptions on programs program. Great! But locations, path names and others things may not be does it, like so many true in all cases, forcing the user to edit the file in other great programs, order to get it to work properly. lack something in terms of ease of installation? Even the Listing 1: A simple Makefile for a GNOME 1: CC=/usr/bin/gcc best and easiest to use programs 2: CFLAGS=`gnome-config —cflags gnome gnomeui` will cause headaches if you have to 3: LDFLAGS=`gnome-config —libs gnome gnomeui` type in lines like this, 4: OBJ=example.o one.o two.o 5: BINARIES=example With the help of gcc -c sourcee.c gnome-config —libs —cflags 6: gnome gnomeui gnomecanvaspixbuf -o sourcee.o 7: all: $(BINARIES) Automake and Autoconf, 8: you can create easily perhaps repeated for each of the files, and maybe 9: example: $(OBJ) with additional compiler flags too, only to then 10: $(CC) $(LDFLAGS) -o $@ $(OBJ) installed source code demand that everything is linked. And at the end, 11: do you then also have to copy the finished binary 12: .c.o: text trees. Read on to 13: $(CC) $(CFLAGS) -c $< manually into the destination directory? Instead, 14: find out how. wouldn’t you rather have an easy, portable and 15: clean: quick installation process? Well, you can – if you 16: rm -rf $(OBJ) $(BINARIES) know how. -

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Developer Guide

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Developer Guide An introduction to application development tools in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Dave Brolley William Cohen Roland Grunberg Aldy Hernandez Karsten Hopp Jakub Jelinek Developer Guide Jeff Johnston Benjamin Kosnik Aleksander Kurtakov Chris Moller Phil Muldoon Andrew Overholt Charley Wang Kent Sebastian Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Developer Guide An introduction to application development tools in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6 Edition 0 Author Dave Brolley [email protected] Author William Cohen [email protected] Author Roland Grunberg [email protected] Author Aldy Hernandez [email protected] Author Karsten Hopp [email protected] Author Jakub Jelinek [email protected] Author Jeff Johnston [email protected] Author Benjamin Kosnik [email protected] Author Aleksander Kurtakov [email protected] Author Chris Moller [email protected] Author Phil Muldoon [email protected] Author Andrew Overholt [email protected] Author Charley Wang [email protected] Author Kent Sebastian [email protected] Editor Don Domingo [email protected] Editor Jacquelynn East [email protected] Copyright © 2010 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. -

Fortran Resources 1

Fortran Resources 1 Ian D Chivers Jane Sleightholme October 17, 2020 1The original basis for this document was Mike Metcalf’s Fortran Information File. The next input came from people on comp-fortran-90. Details of how to subscribe or browse this list can be found in this document. If you have any corrections, additions, suggestions etc to make please contact us and we will endeavor to include your comments in later versions. Thanks to all the people who have contributed. 2 Revision history The most recent version can be found at https://www.fortranplus.co.uk/fortran-information/ and the files section of the comp-fortran-90 list. https://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/cgi-bin/webadmin?A0=comp-fortran-90 • October 2020. Added an entry for Nvidia to the compiler section. Nvidia has integrated the PGI compiler suite into their NVIDIA HPC SDK product. Nvidia are also contributing to the LLVM Flang project. • September 2020. Added a computer arithmetic and IEEE formats section. • June 2020. Updated the compiler entry with details of standard conformance. • April 2020. Updated the Fortran Forum entry. Damian Rouson has taken over as editor. • April 2020. Added an entry for Hewlett Packard Enterprise in the compilers section • April 2020. Updated the compiler section to change the status of the Oracle compiler. • April 2020. Added an entry in the links section to the ACM publication Fortran Forum. • March 2020. Updated the Lorenzo entry in the history section. • December 2019. Updated the compiler section to add details of the latest re- lease (7.0) of the Nag compiler, which now supports coarrays and submodules. -

Winappdbg Documentation Release 1.6

WinAppDbg Documentation Release 1.6 Mario Vilas Aug 28, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Programming Guide 3 i ii CHAPTER 1 Introduction The WinAppDbg python module allows developers to quickly code instrumentation scripts in Python under a Win- dows environment. It uses ctypes to wrap many Win32 API calls related to debugging, and provides a powerful abstraction layer to manipulate threads, libraries and processes, attach your script as a debugger, trace execution, hook API calls, handle events in your debugee and set breakpoints of different kinds (code, hardware and memory). Additionally it has no native code at all, making it easier to maintain or modify than other debuggers on Windows. The intended audience are QA engineers and software security auditors wishing to test or fuzz Windows applications with quickly coded Python scripts. Several ready to use tools are shipped and can be used for this purposes. Current features also include disassembling x86/x64 native code, debugging multiple processes simultaneously and produce a detailed log of application crashes, useful for fuzzing and automated testing. Here is a list of software projects that use WinAppDbg in alphabetical order: • Heappie! is a heap analysis tool geared towards exploit writing. It allows you to visualize the heap layout during the heap spray or heap massaging stage in your exploits. The original version uses vtrace but here’s a patch to use WinAppDbg instead. The patch also adds 64 bit support. • PyPeElf is an open source GUI executable file analyzer for Windows and Linux released under the BSD license. • python-haystack is a heap analysis framework, focused on classic C structure matching. -

Beginning Portable Shell Scripting from Novice to Professional

Beginning Portable Shell Scripting From Novice to Professional Peter Seebach 10436fmfinal 1 10/23/08 10:40:24 PM Beginning Portable Shell Scripting: From Novice to Professional Copyright © 2008 by Peter Seebach All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner and the publisher. ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4302-1043-6 ISBN-10 (pbk): 1-4302-1043-5 ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4302-1044-3 ISBN-10 (electronic): 1-4302-1044-3 Printed and bound in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Trademarked names may appear in this book. Rather than use a trademark symbol with every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use the names only in an editorial fashion and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Lead Editor: Frank Pohlmann Technical Reviewer: Gary V. Vaughan Editorial Board: Clay Andres, Steve Anglin, Ewan Buckingham, Tony Campbell, Gary Cornell, Jonathan Gennick, Michelle Lowman, Matthew Moodie, Jeffrey Pepper, Frank Pohlmann, Ben Renow-Clarke, Dominic Shakeshaft, Matt Wade, Tom Welsh Project Manager: Richard Dal Porto Copy Editor: Kim Benbow Associate Production Director: Kari Brooks-Copony Production Editor: Katie Stence Compositor: Linda Weidemann, Wolf Creek Press Proofreader: Dan Shaw Indexer: Broccoli Information Management Cover Designer: Kurt Krames Manufacturing Director: Tom Debolski Distributed to the book trade worldwide by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., 233 Spring Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10013. -

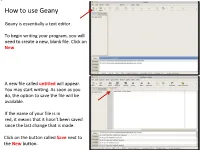

Geany Tutorial

How to use Geany Geany is essentially a text editor. To begin writing your program, you will need to create a new, blank file. Click on New. A new file called untitled will appear. You may start writing. As soon as you do, the option to save the file will be available. If the name of your file is in red, it means that it hasn’t been saved since the last change that is made. Click on the button called Save next to the New button. Save the file in a directory you had previously created before you launched Geany and name it main.cpp. All of the files you will write and submit to will be named specifically main.cpp. Once the .cpp has been specified, Geany will turn on its color coding feature for the C++ template. Next, we will set up our environment and then write a simple program that will print something to the screen Feel free to supply your own name in this small program Before we do anything with it, we will need to configure some options to make your life easier in this class The vertical line to the right marks the ! boundary of your code. You will need to respect this limit in that any line of code you write must not cross this line and therefore be properly, manually broken down to the next line. Your code will be printed out for The line is not where it should be, however, and grading, and if your code crosses the we will now correct it line, it will cause line-wrapping and some points will be deducted. -

Using the GNU Debugger (Gdb) a Debugger Is a Very Useful Tool for Finding Bugs in a Program

Using the GNU debugger (gdb) A debugger is a very useful tool for finding bugs in a program. You can interact with a program while it is running, start and stop it whenever, inspect the current values of variables and modify them, etc. If your program runs and crashes, it will produce a ‘core dump’. You can also use a debugger to look at the core dump and give you extra information about where the crash happened and what triggered it. Some debuggers (including recent versions of gdb) can also go backwards through your code: you run your code forwards in time to the point of an error, and then go backwards looking at the values of the key variables until you get to the start of the error. This can be slow but useful sometimes! To use a debugger effectively, you need to get the compiler to put extra ‘symbol’ information into the binary, otherwise all it will contain is machine code level – it is much more useful to have the actual variable names you used. To do this, you use: gfortran –g –O0 mycode.f90 –o mybinary where ‘-g’ is the compiler option to include extra symbols, -O0 is no optimization so the code is compiled exactly as written, and the output binary is called ’mybinary’. If the source files and executable file is in the same directory, then you can run the binary through the debugger by simply doing: gdb ./mybinary This will then put you into an interactive debugging session. Most commands can be shortened (eg ‘b’ instead of ‘break’) and pressing ‘enter’ will repeat the last command. -

Reference Architecture Specification

Linux based 3G Multimedia Mobile-phone Reference Architecture Specification Draft 1.0 NEC Corporation Panasonic Mobile Communication Ltd. CE Linux Forum Technical Document Contents Preface......................................................................................................................................iii 1. Introduction.............................................................................................................................1 2. Scope .....................................................................................................................................1 3. Reference................................................................................................................................1 4. Definitions and abbreviations ....................................................................................................1 5. Architecture ............................................................................................................................3 5.1 A-CPU ..................................................................................................................................3 5.2 C-CPU..................................................................................................................................5 6. Description of functional entities ..............................................................................................5 6.1 Kernel....................................................................................................................................5 -

The GNOME Desktop Environment

The GNOME desktop environment Miguel de Icaza ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Elliot Lee ([email protected]) Federico Mena ([email protected]) Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, UNAM Tom Tromey ([email protected]) April 27, 1998 Abstract We present an overview of the free GNU Network Object Model Environment (GNOME). GNOME is a suite of X11 GUI applications that provides joy to users and hackers alike. It has been designed for extensibility and automation by using CORBA and scripting languages throughout the code. GNOME is licensed under the terms of the GNU GPL and the GNU LGPL and has been developed on the Internet by a loosely-coupled team of programmers. 1 Motivation Free operating systems1 are excellent at providing server-class services, and so are often the ideal choice for a server machine. However, the lack of a consistent user interface and of consumer-targeted applications has prevented free operating systems from reaching the vast majority of users — the desktop users. As such, the benefits of free software have only been enjoyed by the technically savvy computer user community. Most users are still locked into proprietary solutions for their desktop environments. By using GNOME, free operating systems will have a complete, user-friendly desktop which will provide users with powerful and easy-to-use graphical applications. Many people have suggested that the cause for the lack of free user-oriented appli- cations is that these do not provide enough excitement to hackers, as opposed to system- level programming. Since most of the GNOME code had to be written by hackers, we kept them happy: the magic recipe here is to design GNOME around an adrenaline response by trying to use exciting models and ideas in the applications. -

Fira Code: Monospaced Font with Programming Ligatures

Personal Open source Business Explore Pricing Blog Support This repository Sign in Sign up tonsky / FiraCode Watch 282 Star 9,014 Fork 255 Code Issues 74 Pull requests 1 Projects 0 Wiki Pulse Graphs Monospaced font with programming ligatures 145 commits 1 branch 15 releases 32 contributors OFL-1.1 master New pull request Find file Clone or download lf- committed with tonsky Add mintty to the ligatures-unsupported list (#284) Latest commit d7dbc2d 16 days ago distr Version 1.203 (added `__`, closes #120) a month ago showcases Version 1.203 (added `__`, closes #120) a month ago .gitignore - Removed `!!!` `???` `;;;` `&&&` `|||` `=~` (closes #167) `~~~` `%%%` 3 months ago FiraCode.glyphs Version 1.203 (added `__`, closes #120) a month ago LICENSE version 0.6 a year ago README.md Add mintty to the ligatures-unsupported list (#284) 16 days ago gen_calt.clj Removed `/**` `**/` and disabled ligatures for `/*/` `*/*` sequences … 2 months ago release.sh removed Retina weight from webfonts 3 months ago README.md Fira Code: monospaced font with programming ligatures Problem Programmers use a lot of symbols, often encoded with several characters. For the human brain, sequences like -> , <= or := are single logical tokens, even if they take two or three characters on the screen. Your eye spends a non-zero amount of energy to scan, parse and join multiple characters into a single logical one. Ideally, all programming languages should be designed with full-fledged Unicode symbols for operators, but that’s not the case yet. Solution Download v1.203 · How to install · News & updates Fira Code is an extension of the Fira Mono font containing a set of ligatures for common programming multi-character combinations.