1970 Evidence Convention – the Use of Video-Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wowza Media Server® - Overview

Wowza Media Server® - Overview Wowza® Media Systems, LLC. June 2013, Wowza Media Server version 3.6 Copyright © 2006 – 2013 Wowza Media Systems, LLC. All rights reserved. Wowza Media Server version 3.6 Overview Copyright © 2006 - 2013 Wowza Media Systems, LLC. All rights reserved. This document is for informational purposes only and in no way shall be interpreted or construed to create any warranties of any kind, either express or implied, regarding the information contained herein. Third-Party Information This document contains links to third party websites that are not under the control of Wowza Media Systems, LLC ("Wowza") and Wowza is not responsible for the content on any linked site. If you access a third party website mentioned in this document, then you do so at your own risk. Wowza provides these links only as a convenience, and the inclusion of any link does not imply that Wowza endorses or accepts any responsibility for the content on third party sites. Trademarks Wowza, Wowza Media Systems, Wowza Media Server and related logos are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Wowza Media Systems, LLC in the United States and/or other countries. Adobe and Flash are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Microsoft and Silverlight are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. QuickTime, iPhone, iPad and iPod touch are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Apple, Inc. in the United States and/or other countries. Other product names, logos, designs, titles, words or phrases mentioned may be third party registered trademarks or trademarks in the United States and/or other countries. -

Ellsworth American : August 17, 1876

Cbf £llsiP0rty Kates of Advertisi^f. Li ^nrriran lwk. Swltn. 3 mos. Omoi. I TV. 1 $160 00 $«00 $10 00 IB PCBLISBBD *T inch, $100 $4 3 inches. 3 CO 4 60 ON 15 00 25 0$ 0$ U T 4 column, 8 03 13 00 80 00 48 00 85 i: I.LSWO H, M E, 1 column. 14 0$ 22 00 50 00 86 0$ 100 00 BT TH* Special Notices. One square 3 weeks, $2.00 Each additional week, 50 cents iaacock County Publishing Co moan j Administrator’s and Kxeeutor’s Notices, 1 50 Citation from Probate Court, 8 uO Commissioner’s Notices, 2 8$ T«m« at Messenger’s and Assignee’s Notioti, t-00 SaburiylioB. Editorial Notices, per Tine, -1® Notices, *1® n« copy, n paid within three month*.•'^tK Obituary per line, No charge less than •*w i>»: within three month*,.. if st the end ©t the One inch space will constitute a square. paid year.2 j< Advertisements to be in advaoco. r*ill be discontinued nntil all Transient paid arrear No advertisements reconed less than a *re paid, except at the square. publisher** option— and Deaths inserted free. » person wishing his Marriages sad paper stopped, must to loti'-e thereof at the 1 early advertisers pay quarterly. ( expimtion of the tern • ictner previous notice has been given or not ME., THURSDAY, A.TTCHJST 17, 1870. ELLSWORTH, Tol. MlIdUM-No. 33. Imsiness It was not long after Hus I « (him; which Miss Moggaridge did with her •Aud when It Is all gone/ coutinued Miss expostulation through these Luke Moggaridge* that’1 her willing hands; by the calls of Master i|arbs. -

Website Specifications 20130106

Wowza Media Server® 3.6 Technical Specifications Wowza Media Server® software delivers market-leading functionality, reliability, and flexibility for streaming to any screen across a wide range of industries. Streaming Delivery Adobe Flash® RTMP Flash Player Multi-Protocol, Multi (RTMPE, RTMPT, RTMPTE, RTMPS) Adobe® AIR® Client Adobe Flash HTTP Dynamic Streaming (HDS) RTMP-compatible players HDS-compatible players Apple® HTTP Live Streaming (HLS) iPhone®, iPod®, iPad® (iOS 3.0 or later) QuickTime® Player (10.0 or later) Safari® (4.0 or later on Mac OS X version 10.6) Roku® streaming devices and other HLS-compatible players MPEG DASH DASH-264 Compatible Players Microsoft® Smooth Streaming Silverlight® 3 or later RTSP/RTP Quicktime Player VideoLAN VLC media player 3GPP-compatible mobile devices Other RTSP/RTP-compliant players MPEG2 Transport Protocol (MPEG-TS) IPTV set-top boxes Live Streaming RTMP Video: H.264, VP6, Sorenson Spark®, Screen Video v1 & v2 Compatible Encoding Audio: AAC, AAC-LC, HE-AAC, MP3, Speex, NellyMoser ASAO Inputs RTSP/RTP Video: H.264, H.263 Audio: AAC, AAC-LC, HE-AAC, MP3, Speex MPEG-TS Video: H.264 Audio: AAC, AAC-LC, HE-AAC, E-AC-3, AC-3, MP3 ICY (SHOUTcast/Icecast) Audio: AAC, AAC-LC, HE-AAC (aacPlus), v1 & v2, MP3 Support File Formats Video and Audio FLV (Flash Video - .flv) MP4 (QuickTime container - .mp4, .f4v, .mov, .m4v, .mp4a, .3gp, and .3g2) MP3 (.mp3) PIFF (.ism, .ismc, .ismv, .isma) Protocols and Payloads RTSP IETF RFC2326 RTP:H.264 IETF RFC3984, QuickTime Generic RTP Payload Format RTP:AAC IETF RFC3640, -

Official Journal of the European Union

Official Journal C 399 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 23 November 2020 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES Court of Justice of the European Union 2020/C 399/01 Last publications of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Official Journal of the European Union . 1 Court of Justice 2020/C 399/02 Appointment of the First Advocate General . 2 2020/C 399/03 Designation of the Chamber responsible for cases of the kind referred to in Article 107 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court (urgent preliminary ruling procedure) . 2 2020/C 399/04 Election of the Presidents of the Chambers of three Judges . 2 2020/C 399/05 Taking of the oath by new Members of the Court . 2 2020/C 399/06 Assignment of Judges to Chambers . 3 2020/C 399/07 Lists for the purposes of determining the composition of the formations of the Court . 3 EN V Announcements COURT PROCEEDINGS Court of Justice 2020/C 399/08 Case C-485/18: Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 1 October 2020 (request for a preliminary ruling from the Conseil d’État — France) — Groupe Lactalis v Premier ministre, Garde des Sceaux, ministre de la Justice, Ministre de l’Agriculture et de l’Alimentation, Ministre de l’Économie et des Finances (Reference for a preliminary ruling — Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 — Provision of food information to consumers — Article 9(1)(i) and Article 26(2)(a) — Mandatory indication of the country of origin or place of provenance of foods — Failure to indicate which might -

A Single-Chip MPEG-2 Codec Based on Customizable Media Embedded Processor

530 IEEE JOURNAL OF SOLID-STATE CIRCUITS, VOL. 38, NO. 3, MARCH 2003 A Single-Chip MPEG-2 Codec Based on Customizable Media Embedded Processor Shunichi Ishiwata, Tomoo Yamakage, Yoshiro Tsuboi, Takayoshi Shimazawa, Tomoko Kitazawa, Shuji Michinaka, Kunihiko Yahagi, Hideki Takeda, Akihiro Oue, Tomoya Kodama, Nobu Matsumoto, Takayuki Kamei, Mitsuo Saito, Takashi Miyamori, Goichi Ootomo, and Masataka Matsui, Member, IEEE Abstract—A single-chip MPEG-2 MP@ML codec, integrating microprocessors, such as out-of-order speculative execution, P 3.8M gates on a 72-mm die, is described. The codec employs a branch prediction, and circuit technologies to achieve high heterogeneous multiprocessor architecture in which six micropro- clock frequency, are unsuitable for these application-specific cessors with the same instruction set but different customization execute specific tasks such as video and audio concurrently. processors. On the other hand, the addition of application-spe- The microprocessor, developed for digital media processing, cific instructions and/or hardware engines to accelerate heavy provides various extensions such as a very-long-instruction-word iteration of relatively simple tasks often results in a large gain coprocessor, digital signal processor instructions, and hardware in performance at little additional cost, especially in DSP ap- engines. Making full use of the extensions and optimizing the plications. A heterogeneous multiprocessor architecture using architecture of each microprocessor based upon the nature of specific tasks, the chip can execute not only MPEG-2 MP@ML simple and small microprocessors achieves a better cost–per- video/audio/system encoding and decoding concurrently, but also formance tradeoff than a single high-end general-purpose MPEG-2 MP@HL decoding in real time. -

C370 Official Journal

Official Journal C 370 of the European Union Volume 62 English edition Information and Notices 31 October 2019 Contents II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES European Commission 2019/C 370/01 Communication from the commission Corresponding values of the thresholds of Directives 2014/23/ EU, 2014/24/EU, 2014/25/EU and 2009/81/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (1) . 1 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES Council 2019/C 370/02 Council Decision of 24 October 2019 on the appointment of a Deputy Executive Director of Europol . 4 European Commission 2019/C 370/03 Euro exchange rates — 30 October 2019 . 6 2019/C 370/04 Explanatory Notes to the Combined Nomenclature of the European Union . 7 European External Action Service 2019/C 370/05 Decision of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of 1 October 2019 on implementing rules relating to the protection of personal data by the European External Action Service and the application of Regulation (EU) 2018/1725 of the European Parliament and of the Council . 9 2019/C 370/06 Decision of the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of 1 October 2019 on internal rules concerning restrictions of certain rights of data subjects in relation to processing of personal data in the framework of the functioning of the European External Action Service . 18 EN (1) Text with EEA relevance. European Data Protection Supervisor 2019/C 370/07 Summary of the Opinion of the European Data Protection Supervisor on the revision of the EU Regulations on service of documents and taking of evidence in civil or commercial matters (The full text of this Opinion can be found in English, French and German on the EDPS website www.edps.europa.eu) . -

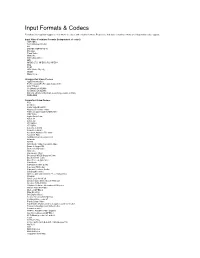

Input Formats & Codecs

Input Formats & Codecs Pivotshare offers upload support to over 99.9% of codecs and container formats. Please note that video container formats are independent codec support. Input Video Container Formats (Independent of codec) 3GP/3GP2 ASF (Windows Media) AVI DNxHD (SMPTE VC-3) DV video Flash Video Matroska MOV (Quicktime) MP4 MPEG-2 TS, MPEG-2 PS, MPEG-1 Ogg PCM VOB (Video Object) WebM Many more... Unsupported Video Codecs Apple Intermediate ProRes 4444 (ProRes 422 Supported) HDV 720p60 Go2Meeting3 (G2M3) Go2Meeting4 (G2M4) ER AAC LD (Error Resiliant, Low-Delay variant of AAC) REDCODE Supported Video Codecs 3ivx 4X Movie Alaris VideoGramPiX Alparysoft lossless codec American Laser Games MM Video AMV Video Apple QuickDraw ASUS V1 ASUS V2 ATI VCR-2 ATI VCR1 Auravision AURA Auravision Aura 2 Autodesk Animator Flic video Autodesk RLE Avid Meridien Uncompressed AVImszh AVIzlib AVS (Audio Video Standard) video Beam Software VB Bethesda VID video Bink video Blackmagic 10-bit Broadway MPEG Capture Codec Brooktree 411 codec Brute Force & Ignorance CamStudio Camtasia Screen Codec Canopus HQ Codec Canopus Lossless Codec CD Graphics video Chinese AVS video (AVS1-P2, JiZhun profile) Cinepak Cirrus Logic AccuPak Creative Labs Video Blaster Webcam Creative YUV (CYUV) Delphine Software International CIN video Deluxe Paint Animation DivX ;-) (MPEG-4) DNxHD (VC3) DV (Digital Video) Feeble Files/ScummVM DXA FFmpeg video codec #1 Flash Screen Video Flash Video (FLV) / Sorenson Spark / Sorenson H.263 Forward Uncompressed Video Codec fox motion video FRAPS: -

Wowza Media Server® 3

® Wowza Media Server 3 User’s Guide Copyright © 2006 - 2012 Wowza Media Systems, LLC All rights reserved. Wowza Media Server 3: User’s Guide Version: 3.1 Copyright 2006 – 2012 Wowza Media Systems, LLC http://www.wowza.com Copyright © 2006 - 2012 Wowza Media Systems, LLC All rights reserved. This document is for informational purposes only and in no way shall be interpreted or construed to create any warranties of any kind, either express or implied, regarding the information contained herein. Third Party Information This document contains links to third party websites that are not under the control of Wowza Media Systems, LLC (“Wowza”) and Wowza is not responsible for the content on any linked site. If you access a third party website mentioned in this document, then you do so at your own risk. Wowza provides these links only as a convenience, and the inclusion of any link does not imply that Wowza endorses or accepts any responsibility for the content on third party sites. This document refers to third party software that is not licensed, sold, distributed or otherwise endorsed by Wowza. Please ensure that any and all use of Wowza® software and third party software is properly licensed. Trademarks Wowza, Wowza Media Systems, Wowza Media Server and related logos are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Wowza Media System, LLC in the United States and/or other countries. Adobe and Flash are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. Microsoft and Silverlight are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. -

Scape D10.1 Keeps V1.0

Identification and selection of large‐scale migration tools and services Authors Rui Castro, Luís Faria (KEEP Solutions), Christoph Becker, Markus Hamm (Vienna University of Technology) June 2011 This work was partially supported by the SCAPE Project. The SCAPE project is co-funded by the European Union under FP7 ICT-2009.4.1 (Grant Agreement number 270137). This work is licensed under a CC-BY-SA International License Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Scope of this document 1 2 Related work 2 2.1 Preservation action tools 3 2.1.1 PLANETS 3 2.1.2 RODA 5 2.1.3 CRiB 6 2.2 Software quality models 6 2.2.1 ISO standard 25010 7 2.2.2 Decision criteria in digital preservation 7 3 Criteria for evaluating action tools 9 3.1 Functional suitability 10 3.2 Performance efficiency 11 3.3 Compatibility 11 3.4 Usability 11 3.5 Reliability 12 3.6 Security 12 3.7 Maintainability 13 3.8 Portability 13 4 Methodology 14 4.1 Analysis of requirements 14 4.2 Definition of the evaluation framework 14 4.3 Identification, evaluation and selection of action tools 14 5 Analysis of requirements 15 5.1 Requirements for the SCAPE platform 16 5.2 Requirements of the testbed scenarios 16 5.2.1 Scenario 1: Normalize document formats contained in the web archive 16 5.2.2 Scenario 2: Deep characterisation of huge media files 17 v 5.2.3 Scenario 3: Migrate digitised TIFFs to JPEG2000 17 5.2.4 Scenario 4: Migrate archive to new archiving system? 17 5.2.5 Scenario 5: RAW to NEXUS migration 18 6 Evaluation framework 18 6.1 Suitability for testbeds 19 6.2 Suitability for platform 19 6.3 Technical instalability 20 6.4 Legal constrains 20 6.5 Summary 20 7 Results 21 7.1 Identification of candidate tools 21 7.2 Evaluation and selection of tools 22 8 Conclusions 24 9 References 25 10 Appendix 28 10.1 List of identified action tools 28 vi 1 Introduction A preservation action is a concrete action, usually implemented by a software tool, that is performed on digital content in order to achieve some preservation goal. -

Apostille Handbook Osapostille

Ap Aphague conference on private international law os Handbook Apostille osApostille Handbook A Handbook t l t l on the Practical Operation of the Apostille les les Convention Apostille Handbook A Handbook on the Practical Operation of the Apostille Convention Published by The Hague Conference on Private International Law Permanent Bureau Churchillplein 6b, 2517 JW The Hague The Netherlands Telephone: +31 70 363 3303 Fax: +31 70 360 4867 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.hcch.net © Hague Conference on Private International Law 2013 Reproduction of this publication is authorised, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN 978-94-90265-08-3 Printed in The Hague, the Netherlands Foreword The Handbook is the final publication in a series of three produced by the Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law on the Apostille Convention following a recommendation of the 2009 meeting of the Special Commission on the practical operation of the Convention. hague conference on private international law The first publication is a brochure entitled “The ABCs of Apostilles”, which is The ABCs primarily addressed to users of the Apostille system (namely the individuals and of Apostilles How to ensure businesses involved in cross-border activities) by providing them with short and that your public documentsA will practical answers to the most frequently asked questions. t be recognised abroad o The second publication is a brief guide entitled hague conference on private international -

“Praxis Des Internationalen Privat- Und Verfahrensrechts” (6/2008)

Latest Issue of “Praxis des Internationalen Privat- und Verfahrensrechts” (6/2008) Recently, the November/December issue of the German legal journal “Praxis des Internationalen Privat- und Verfahrensrechts” (IPRax) was released. It contains the followingarticles/case notes (including the reviewed decisions): B. Hess: “Rechtspolitische Überlegungen zur Umsetzung von Art. 15 der Europäischen Zustellungsverordnung – VO (EG) Nr. 1393/2007” – the English abstract reads as follows: The article deals with article 15 EC Regulation on Serviceof Documents as revised by Regulation (EC) No 1393/2007 on the service in the Member States of judicial and extrajudicial documents in civil or commercial matters. The author recommends to extend the application of cross border direct service of documents within the EU under German law and in this context makes a concrete proposal for the implementation of article 15 into a revised article 1071 German Code of Civil Procedure. C. Heinze: “Beweissicherung im europäischen Zivilprozessrecht” – the English abstract reads as follows: Measures to preserve evidence for judicial proceedings are of vital importance for any claimant trying to prove facts which are outside his own sphere of influence. The procedural laws in Europe differ in their approach to such measures: while some regard them as a form of provisional relief, others consider these measures to be part of the evidentiary proceedings before the court. In European law, evidence measures lie at the intersection of three different enactments of the Community, namelyRegulation (EC) No 1206/2001 on cooperation between the courts of the Member States in the taking of evidence in civil or commercial matters, Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters and (in intellectual property disputes) Art. -

Supported Codecs and Formats Codecs

Supported Codecs and Formats Codecs: D..... = Decoding supported .E.... = Encoding supported ..V... = Video codec ..A... = Audio codec ..S... = Subtitle codec ...I.. = Intra frame-only codec ....L. = Lossy compression .....S = Lossless compression ------- D.VI.. 012v Uncompressed 4:2:2 10-bit D.V.L. 4xm 4X Movie D.VI.S 8bps QuickTime 8BPS video .EVIL. a64_multi Multicolor charset for Commodore 64 (encoders: a64multi ) .EVIL. a64_multi5 Multicolor charset for Commodore 64, extended with 5th color (colram) (encoders: a64multi5 ) D.V..S aasc Autodesk RLE D.VIL. aic Apple Intermediate Codec DEVIL. amv AMV Video D.V.L. anm Deluxe Paint Animation D.V.L. ansi ASCII/ANSI art DEVIL. asv1 ASUS V1 DEVIL. asv2 ASUS V2 D.VIL. aura Auravision AURA D.VIL. aura2 Auravision Aura 2 D.V... avrn Avid AVI Codec DEVI.. avrp Avid 1:1 10-bit RGB Packer D.V.L. avs AVS (Audio Video Standard) video DEVI.. avui Avid Meridien Uncompressed DEVI.. ayuv Uncompressed packed MS 4:4:4:4 D.V.L. bethsoftvid Bethesda VID video D.V.L. bfi Brute Force & Ignorance D.V.L. binkvideo Bink video D.VI.. bintext Binary text DEVI.S bmp BMP (Windows and OS/2 bitmap) D.V..S bmv_video Discworld II BMV video D.VI.S brender_pix BRender PIX image D.V.L. c93 Interplay C93 D.V.L. cavs Chinese AVS (Audio Video Standard) (AVS1-P2, JiZhun profile) D.V.L. cdgraphics CD Graphics video D.VIL. cdxl Commodore CDXL video D.V.L. cinepak Cinepak DEVIL. cljr Cirrus Logic AccuPak D.VI.S cllc Canopus Lossless Codec D.V.L.