Robin Hood's Guyde to Being the Merriest Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood of Great Renown in Nottinghamshire

GIFT OF Mrs. S. Einarsson Advent ures-of. I 1 heTAerry-Friar-carriefh Robia-acro/VfheWater : %??VV' V THE MERRY ADVENTURES of ROBIN HOOD of Great Renown, in Nottinghamshire . WRITTEN and ILLUSTRATED W\ By HOWARD PYLE. NEW YORK-. Printed by CHARLES SCR IBNER'S SONS A^.743^74 5 Broadway, and sold by same MDCCCLXXXIU. Copyright, 1883, By CHARLES SCKIBNER'S SONS. From the Author to the Reader. U who so plod amid serious things that you feel it shame to give even a short moments to mirth and rOyourself tip for few joyous- in the land think that ness of Fancy ; you who life hath nought to do with innocent laughter that can harm no one ; these pages are not to the leaves and no than this I tell for you. Clap go farther ', for you plainly that if you go farther you will be scandalized by seeing good, sober folks of real history so frisk and caper in gay colors and motley, that you would not know them but for the names tagged to them. Here is a stout, lusty fellow with a quick temper, yet none so ill for all that, who goes by the name of Henry II. Here is a fair, gentle lady before whom all the others bow and call her Queen Eleanor. Here is a fat rogue of a fellow, dressed up in rich robes of a clerical kind, that all the good folk call my Lord Bishop of Hereford. Here is a certain fellow with a sour temper and a grim look the worshipful, the Sheriff of Nottingham. -

King John in Fact and Fiction

W-i".- UNIVERSITY OF PENNS^XVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WALLERSTEIN ff DA 208 .W3 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARY ''Ott'.y^ y ..,. ^..ytmff^^Ji UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA KING JOHN IN FACT AND FICTION BY RUTH WAIXE510TFIN. A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GiLA.DUATE SCHOOL IN PARTLVL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 'B J <^n5w Introductory LITTLE less than one hundred years after the death of King John, a Scottish Prince John changed his name, upon his accession to L the and at the request of his nobles, A throne to avoid the ill omen which darkened the name of the English king and of John of France. A century and a half later, King John of England was presented in the first English historical play as the earliest English champion and martyr of that Protestant religion to which the spectators had newly come. The interpretation which thus depicted him influenced in Shakespeare's play, at once the greatest literary presentation of King John and the source of much of our common knowledge of English history. In spite of this, how- ever, the idea of John now in the mind of the person who is no student of history is nearer to the conception upon which the old Scotch nobles acted. According to this idea, John is weak, licentious, and vicious, a traitor, usurper and murderer, an excommunicated man, who was com- pelled by his oppressed barons, with the Archbishop of Canterbury at their head, to sign Magna Charta. -

Pride Lineup R Ee Qb

F PRIDE LINEUP R EE QB Nottinghamshire’s Queer Bulletin August/September 2011 Number 61 The Pride stage will undergo meiosis and divide into 4. As well as the Main Stage (hosted by Harry Derbridge - from “The only way is Essex”), Politicians experience often scath- you can enjoy the Acoustic Stage, the Comedy Stage and a family zone - ing criticism on a daily basis in our The Village Green. Some of the performers featured are listed below. newspapers. On radio and televi- sion they are subject to the mock- MAIN STAGE ACOUSTIC STAGE COMEDY STAGE ery which is part of a tradition going Booty Luv Kenelis Julie Jepson back to - at least - the ancient Ruth Lorenzo Maniére des Suzi Ruffle Greeks. Cartoonists have a field day. David Cameron is portrayed Drag with No Name Bohémiens Rosie Wilby by one as a "Little Lord Fauntleroy" Fat Digester Gallery 47 Rachel Stubbins type and by another as a pink hu- Propaganda Betty Munroe & Josephine Ettrick-Hogg man condom with big wobbly Danny Stafford The Blue Majestix Carly Smallman Youth Spot The Idolins breasts. VILLAGE GREEN Jo Francis Emily Franklin Our mockery and fact-based criti- Captain Dangerous Wax Ersatz Asian Dance Group cisms of Kay Cutts pale beside this Vibebar May KB Pirate Show and beside what one reads on the Benjamin Bloom Selma Thurman Carlton Brass Band local Parish of Nottinghamshire Grey Matter Ball Bois display website, to which we referred. Poli- The Cedars Hosts: John Gill & Dog display team ticians need broad shoulders. Bear- NG1/@D2 Princess Babserella Tatterneers Band ing in mind the size of Mrs Cutts' "shoulders", the County Library QB ban is utterly predictable. -

For Children 1

1 500BOOKS FOR CHILDREN 1 NORA E. BEUST Specialist in School Libraries /114.4 14. or, . 11 4 -es . - ,0 I . A PW oh Bulletin 1939, No. 11 It t<1 maim STATICS DEPARTMENT OPTILEINTERIOR,HaroldL. Ickes,Seeman MIMIOFIDUCATION, J. W. Studebaker,Ceuradosiesar ailed States GarmasheetPrintingMks Wesklegtsa 44t re Oa tif fla 011111010111,stOfDmINIIN, WasiOntra,D. A hieslasea* . ,': i ....- ,..- i: : ... 4.1 :. - '' , .t t^ bayV . - - .4,)' 4: I r * $'` :f . o W...1*- 4"4'-' ' .''... r . 4l 4.47. .5 14.11$f 4'.'t :..!`'.: t I ' . r :" ' gi ' ,k, i 4't, 'I: - 4 , ' '... ..!1' 'et i; s :- i . 7.% t . t .. nzs 1 - 7,...., k trd, '; "'" ". , e" e 7 4 , J t, RAY, Ars "274LV,INi .th Wei LW" lb 1 s . CONTENTS Page FOREWORD_ 01, 411. v bi PRIPIACZ _ SECTIONI (Grades 1-3)__ 6 SECTIONII (Grades 4-6) ,. .......... - - - ........___ 20 , SECTIONIII (Grades 7-8) 38 NEWBRRTMEI3AL BOOKS _ 53 CALDICOTI' AWARDS__IMP MO OW as I ND 55 ILLUSTRATORS 59 PuBusaxas. 66 k hoax_ 110 am, airo 69 vt, In I 1 *0' e. 7t. ' A. " -.Or' ' ,s a __,* '--. .4- a .I, ,,,e vala. a,ra ., . * * i f, Or . N, :' * 10 ara.." .1,-*-vot. 1 v.irjrr; ,- ''4" 1,4-*vf.1.4 5 at: IC .._." 1. 1 ''''', , -4` -. % ... t p - _., J:, tit .3,..7" t. '-,,,....,....;lf,- riit, t,..12 ..PFle-... re .0* - .).... 1- . - ' .i. 41; , '9.14 a Onegift thefairiesgave me.(Three Theycommonlybestowedof yore.) Thelove ofbooks,the goldenkey Thatopenstheenchanteddoor. IOW ANDREW LANG. FromBallade oftheBookworm. Iv- - - 4. -'k,' 7 t45.11.. et* 0. -

Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham

Early Theatre 14.1 (2011) Alexis Butzner ‘Sette on foote with gode Wyll’: Towards a Reconstruction of Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham Lythe and listin, gentilmen, That be of frebore blode; I shall you tel of a gode yeman, His name was Robyn Hode. A Gest of Robyn Hode1 In the greenwood of England, a game is afoot. Robin Hood, the noble ban- dit, has been identified as the audacious hero of Sherwood and Barnsdale for centuries, and his constant presence in ballads and drama since the four- teenth century attests to his popularity in and influence on the culture of the English nation. In a manuscript fragment of the late fifteenth century,2 the legend finds incarnation in a twenty-one-line drama (forty-two, if the caesurae are recognized instead as line-breaks), known by most scholars as Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham. The text contains no indication of scene-divisions or stage directions, and does not offer any notation to indi- cate the identity of the various speakers. Because the text offers so little in the way of definite answers, it invites interpretation. Despite their admirable efforts to treat the fragment, however, scholars have reached little consensus: critics, while advancing the probable accuracy of their own reconstructions, have yet to resolve some crucial difficulties that arise in the extant text. By reading the script Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham as a single and complete play-text, as I do in this re-examination, readers may reconcile its apparent inconsistencies. Since the first extant record of Robin Hood in literature, in the four- teenth century Piers Plowman, tales and rhymes of the legendary outlaw have permeated Anglophone culture — a feat of public memory that, according to Stephen Knight, is surpassed only by stories of King Arthur.3 That the Robin Hood legend survives — and thrives — should not come as a shock; 61 62 Alexis Butzner even in his earliest incarnations, he occupies a liminal space between social strata. -

Robin Hood Was Smiling

CHAPTER 1 Trouble at Treeton Mine Every day at Treeton Mine was terrible, but today was worse than all the others. Clouds of black smoke covered the sky. Everywhere people lay hurt or dead. The terrible explosion at the mine was still sounding in people’s ears. Rowan found his father. He was sitting by the body of his uncle and crying. ‘He’s dead, Rowan. They’re all dead.’ Rowan pointed at some men on horses. They were riding towards the mine. ‘Look, Father. Here’s Gisborne. Slowly, the Sheriff got off his horse. ‘I hope you’re not Please tell him. The mine is too dangerous. We can’t work giving these people a choice, Gisborne,’ he said softly. here anymore.’ Gisborne looked at him. Then he took his knife and Sir Guy of Gisborne was dark and good-looking but his pushed it into the miner’s body. Rowan couldn’t believe it. eyes were hard and cold. He got off his horse and looked His father fell onto the grass, dead. at all the dead bodies. Rowan’s father ran to him. ‘Very good,’ said the Sheriff happily. Then he turned to ‘We’re not going to work in your mine anymore, the miners with a small, thin smile. ‘Enjoy your free time. Gisborne. We can’t. It isn’t safe. Make it safe and we’ll go You’ve lost your jobs. Goodbye.’ He started to walk away. back to work.’ Gisborne followed him. He didn’t understand. ‘But we Gisborne was angry. ‘You work when I tell you!’ he need miners. -

Chapter One: Introduction 1

Feminism, citizenship and social activity: The role and importance of local women’s organisations, Nottingham 1918-1969 Samantha Clements, B.A., M.A. Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2008 ABSTRACT This local study of single-sex organisations in Nottingham and Nottinghamshire is an attempt to redress some of the imbalanced coverage given to this area of history thus far. A chronological study, it examines the role, importance and, to some extent, impact of a wide range of women’s organisations in the local context. Some were local branches of national organisations, others were specifically concerned with local issues. The local focus allows a challenge to be made to much current thought as to the strength of a “women’s movement” in the years between the suffrage movement and the emergence of a more radical form of feminism in the 1970s. The strength of feminist issues and campaigning is studied in three periods – the inter-war period, the Second World War and its immediate aftermath, and the 1950s and 1960s. The first two periods have previously been studied on a national level but, until recently, the post-Second World war era has been written off as overwhelmingly domestic and therefore unconstructive to the achievement of any feminist aims. This study suggests that, at a local level, this is not the case and that other conclusions reached about twentieth century feminism at a national level are not always applicable to the local context. The study also goes further than attempting to track interest in equality feminism in the mid years of the century by discussing the importance of citizenship campaigns and the social dimension of membership of women’s organisations. -

Treacherous 'Saracens' and Integrated Muslims

TREACHEROUS ‘SARACENS’ AND INTEGRATED MUSLIMS: THE ISLAMIC OUTLAW IN ROBIN HOOD’S BAND AND THE RE-IMAGINING OF ENGLISH IDENTITY, 1800 TO THE PRESENT 1 ERIC MARTONE Stony Brook University [email protected] 53 In a recent Associated Press article on the impending decay of Sherwood Forest, a director of the conservancy forestry commission remarked, “If you ask someone to think of something typically English or British, they think of the Sherwood Forest and Robin Hood… They are part of our national identity” (Schuman 2007: 1). As this quote suggests, Robin Hood has become an integral component of what it means to be English. Yet the solidification of Robin Hood as a national symbol only dates from the 19 th century. The Robin Hood legend is an evolving narrative. Each generation has been free to appropriate Robin Hood for its own purposes and to graft elements of its contemporary society onto Robin’s medieval world. In this process, modern society has re-imagined the past to suit various needs. One of the needs for which Robin Hood has been re-imagined during late modern history has been the refashioning of English identity. What it means to be English has not been static, but rather in a constant state of revision during the past two centuries. Therefore, Robin Hood has been adjusted accordingly. Fictional narratives erase the incongruities through which national identity was formed into a linear and seemingly inevitable progression, thereby fashioning modern national consciousness. As social scientist Etiénne Balibar argues, the “formation of the nation thus appears as the fulfillment of a ‘project’ stretching over centuries, in which there are different stages and moments of coming to self-awareness” (1991: 86). -

Meeple University Guide to Robin Hood and the Merry Men

Meeple University Guide to Robin Hood and the Merry Men MERRY MEN PHASE 3. Guy of Gisborne (breastplate icon) 11. Free prisoners (tower icon) Take income, then place meeples one at a time - Remove closest barricade to the castle (return to player's lair) - Spend distraction tokens, roll two skill dice per token Two types of actions: active (stronger) and passive (weaker). - Advance carriage to castle if it is now unimpeded (see below) - Free prisoners based on number of successes (see below) Active meeples in hideouts, passive meeples in main area. - Gain rewards from Sheriff's stash (see below) No passive action for construction yard or crusade. 4. Prince John (crown icon) - Return Merry Men to owner; gain VP if belongs to opponent - Remove pennies equal to barricades (including the printed one) • From Prison I, needs 1 success, earn 2VP and one reward To take active action, play matching card from hand or passive pile • From Prison II, needs 2 successes, earn 3VP and two rewards To take passive action, play any card from hand to passive pile 5. Activate a road (carriage icon) • From Prison III, needs 3 successes, earn 4VP and three rewards - Advance all carriages one barricade Passive pile has max six cards (can discard), worth VP at end game - Add carriage to the head of the road 12. Archery competition (target icon) 1-5. Gathering sites (circular shield icons) - If carriage enters castle: - Roll skill dice per the level, gain pennies for each success - Take resource matching the site • Place carriage upright on the lot (top to bottom, left to right) - Can attempt each level in sequence until suffering one failure - Cannot hold more than four weapon dice at any time • Pay pennies from the road per the space covered - No additional penalty for failure - If carriage lot fills: 6. -

Policing in the 21St Century

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee Policing in the 21st Century Seventh Report of Session 2007–08 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 30 October 2008 HC 364-II Published on 10 October 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Keith Vaz MP (Labour, Leicester East) (Chairman) Tom Brake MP (Liberal Democrat, Charshalton and Wallington) Ms Karen Buck MP (Labour, Regent’s Park and Kensington North) Mr James Clappison MP (Conservative, Hertsmere) Mrs Ann Cryer MP (Labour, Keighley) David TC Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Mrs Janet Dean MP (Labour, Burton) Patrick Mercer MP (Conservative, Newark) Margaret Moran MP (Labour, Luton South) Gwyn Prosser MP (Labour, Dover) Bob Russell MP (Liberal Democrat, Colchester) Martin Salter MP (Labour, Reading West) Mr Gary Streeter MP (Conservative, South West Devon) Mr David Winnick MP (Labour, Walsall North) The following Member was also a Member of the Committee during the inquiry: Mr Jeremy Browne MP (Liberal Democrat, Taunton) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Maid Marian Maid Marian Fitzwalter Was Born in 1173 at the Old Bilborough Hall, Which Is Now Harvey Hadden Leisure Centre

Maid Marian Maid Marian Fitzwalter was born in 1173 at the old Bilborough Hall, which is now Harvey Hadden Leisure Centre. It was Marian’s family who had commissioned the building of St Martins church in Bilborough, near where they lived, to be built – a project which Little John had worked on a site labourer. Marian was a free spirit. Rejecting her family’s status and wealth, she spent more time with the regular folk in Bilborough or in the nearby deer park at Wollaton than with the landed aristocracy. It is during this time she met a young Robin, who was living in the area. They remained friends whilst Robin was away during the Crusades. It is during this time that Marian was promised to be married to Eustachius de Moreton, Lord of Wollaton and Algarthorpe (in modern day Basford). Marian was not happy with the match and broke off the engagement, waiting for Robin to return. Eustachius, unhappy that Marian had broken it off, challenged her to a horse race from Algarthorpe to Woodthorpe, the finish line now where the house in Woodthorpe Park stands. Marian won easily and the chided Eustachius returned to Basford. When Robin returned, the two fell in love and she quickly became an important ally in the fight against the evil Sherriff. She was an able spy and lockpick who would help Robin and his outlaw companions whilst still appearing to be a lady of the court. She could pass through Nottingham and its Castle as she pleased, gleaning useful information. Marian received many the scornful look as she cheered on the disguised Robin during the Golden Arrow competition on what is now the Forest Recreation ground and remained to see Robin and his companions share the spoils of his win with the people of Hyson Green. -

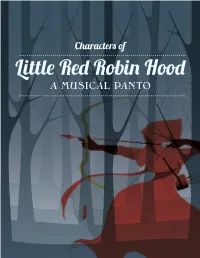

Little Red Robin Hood CHARACTER SCHEDULE

Characters of Little Red Robin Hood CHARACTER SCHEDULE AMELIA, A.K.A. LITTLE RED ROBIN HOOD The young heroine of our panto. The forest creatures nickname Amelia “Little Red Robin Hood” because of her red cloak and how she reminds them of their long-lost savior, Robin Hood. She is a strong-willed, fifteen-year- old orphan with a knack for archery and a determination to save Sherwood Forest. MAUD A.K.A. THE GRANNY IN THE WOODS The Granny is a classic character from Little Red Riding Hood, but Maud is much more than a wolf’s dinner. She fights side-by-side with Little Red against a greedy villainess, inspires the whole forest with her letters to the editor, and is the dame of this panto! What’s a dame, you ask? In basic terms, the dame is the beloved matriarch of any panto, and is always a drag role – think Robin Williams in Mrs. Doubtfire. LADY NOTTINGHAM Unlike Maud and Amelia, Lady Nottingham doesn’t have a direct fairytale counterpart. She’s the villain of our story and is a sort of combination between Prince John from Disney’s cartoon Robin Hood and Cersei Lannister from Game of Thrones. CHARACTER SCHEDULE LUPO The big bad wolf of our story isn’t really that big, and truly isn’t that bad, either. Lupo gets caught up in a bad crowd working for Lady Nottingham, but doesn’t want to eat Little Red or her Granny like in the original tales. He serves as more of a narrator in our version.