Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone Girl : a Novel / Gillian Flynn

ALSO BY GILLIAN FLYNN Dark Places Sharp Objects This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at [email protected] or (212) 572-2013. http://www.rhspeakers.com/ This book is a work of ction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used ctitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2012 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Dark Places” copyright © 2009 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Sharp Objects” copyright © 2006 by Gillian Flynn All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Gillian, 1971– Gone girl : a novel / Gillian Flynn. p. cm. 1. Husbands—Fiction. 2. Married people—Fiction. 3. Wives—Crimes against—Fiction. I. Title. PS3606.L935G66 2012 813’.6—dc23 2011041525 eISBN: 978-0-307-58838-8 JACKET DESIGN BY DARREN HAGGAR JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BERND OTT v3.1_r5 To Brett: light of my life, senior and Flynn: light of my life, junior Love is the world’s innite mutability; lies, hatred, murder even, are all knit up in it; it is the inevitable blossoming of its opposites, a magnicent rose smelling faintly of blood. -

Knut Hamsun at the Movies in Transnational Contexts

KNUT HAMSUN AT THE MOVIES IN TRANSNATIONAL CONTEXTS Arne Lunde This article is a historical overview that examines how the literary works of Knut Hamsun have been adapted into films over the past century. This “Cook’s Tour” of Hamsun at the movies will trace how different national and transnational cinemas have appropri- ated his novels at different historical moments. This is by no means a complete and exhaustive overview. The present study does not cite, for example, Hamsun films made for television or non-feature length Hamsun films. Thus I apologize in advance for any favorite Hamsun-related films that may have been overlooked. But ideally the article will address most of the high points in the international Hamsun filmography. On the subject of the cinema, Hamsun is famously quoted as having said in the 1920s: “I don’t understand film and I’m at home in bed with the flu” (Rottem 2). Yet while Hamsun was volun- tarily undergoing psychoanalysis in Oslo in 1926, he writes to his wife Marie about wishing to learn to dance and about going to the movies more (Næss 129). Biographer Robert Ferguson reports that in 1926, Hamsun began regularly visiting the cinemas in Oslo “taking great delight in the experience, particularly enjoying adventure films and comedies” (Ferguson 286). So we have the classic Hamsun paradox of conflicting statements on a subject, in this case the movies. Meanwhile, it is also important to remember that the films that Hamsun saw in 1926 would still have been silent movies with intertitles and musical accompaniment, and thus his poor hearing would not have been an impediment to his enjoyment. -

(#) Indicates That This Book Is Available As Ebook Or E

ADAMS, ELLERY 11.Indigo Dying 6. The Darling Dahlias and Books by the Bay Mystery 12.A Dilly of a Death the Eleven O'Clock 1. A Killer Plot* 13.Dead Man's Bones Lady 2. A Deadly Cliché 14.Bleeding Hearts 7. The Unlucky Clover 3. The Last Word 15.Spanish Dagger 8. The Poinsettia Puzzle 4. Written in Stone* 16.Nightshade 9. The Voodoo Lily 5. Poisoned Prose* 17.Wormwood 6. Lethal Letters* 18.Holly Blues ALEXANDER, TASHA 7. Writing All Wrongs* 19.Mourning Gloria Lady Emily Ashton Charmed Pie Shoppe 20.Cat's Claw 1. And Only to Deceive Mystery 21.Widow's Tears 2. A Poisoned Season* 1. Pies and Prejudice* 22.Death Come Quickly 3. A Fatal Waltz* 2. Peach Pies and Alibis* 23.Bittersweet 4. Tears of Pearl* 3. Pecan Pies and 24.Blood Orange 5. Dangerous to Know* Homicides* 25.The Mystery of the Lost 6. A Crimson Warning* 4. Lemon Pies and Little Cezanne* 7. Death in the Floating White Lies Cottage Tales of Beatrix City* 5. Breach of Crust* Potter 8. Behind the Shattered 1. The Tale of Hill Top Glass* ADDISON, ESME Farm 9. The Counterfeit Enchanted Bay Mystery 2. The Tale of Holly How Heiress* 1. A Spell of Trouble 3. The Tale of Cuckoo 10.The Adventuress Brow Wood 11.A Terrible Beauty ALAN, ISABELLA 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 12.Death in St. Petersburg Amish Quilt Shop House 1. Murder, Simply Stitched 5. The Tale of Briar Bank ALLAN, BARBARA 2. Murder, Plain and 6. The Tale of Applebeck Trash 'n' Treasures Simple Orchard Mystery 3. -

The Validity of Human Language: a Vehicle for Divine Truth

Grace Theological Journal 9.1 (1988) 21-43 [Copyright © 1988 Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission; digitally prepared for use at Gordon and Grace Colleges and elsewhere] THE VALIDITY OF HUMAN LANGUAGE: A VEHICLE FOR DIVINE TRUTH JACK BARENTSEN Doubts have arisen about the adequacy of human language to convey inerrant truth from God to man. These doubts are rooted in an empirical epistemology, as elaborated by Hume, Kant, Heidegger and others. Many theologians adopted such an empirical view and found themselves unable to defend a biblical view of divine, inerrant revelation. Barth was slightly more successful, but in the end he failed. The problem is the empirical epistemology that first analyzes man's relationship with creation. Biblically, the starting point should be an analysis of man's relationship with his Creator. When ap- proached this way, creation (especially the creation of man in God's image) and the incarnation show that God and man possess an adequate, shared communication system that enables God to com- municate intelligibly and inerrantly with man. Furthermore, the Bible's insistence on written revelation shows that inerrant divine communication carries the same authority whether written or spoken. * * * As a result of the materialistic, empirical scepticism of the last two centuries, many theologians entertain doubts about the ade- quacy of human language to convey divine truth (or, in some cases, to convey truth of any kind). This review of the philosophical and theological origins of the current doubts about language lays a foundation for a biblical view of language. THE CONTEMPORARY PROBLEM One recent writer stated the problem of the adequacy of religious language in these words: The problem of religious knowledge, in the context of contemporary philosophical analysis, is basically this: no one has any. -

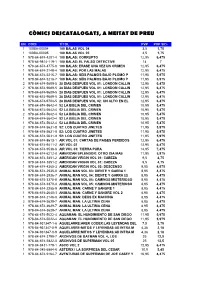

Llistat Còmics Descatalogats.Xml

CÒMICS DESCATALOGATS, A MEITAT DE PREU UN. CODI TÍTOL PVP PVP 50% 1 100BA-00004 100 BALAS VOL 04 3,5 1,75 1 100BA-00005 100 BALAS VOL 05 3,5 1,75 1 978-84-674-4201-4 100 BALAS: CORRUPTO 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-9814-119-1 100 BALAS: EL FALSO DETECTIVE 14 7 1 978-84-674-4775-0 100 BALAS: ERASE UNA VEZ UN CRIMEN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-2148-4 100 BALAS: POR LAS MALAS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9704-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 02: UN ALTO EN EL 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 5 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 3 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-8613-1 AIR VOL 01: CARTAS DE PAISES PERDIDOS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9411-2 AIR VOL 02 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9538-6 AIR VOL 03: TIERRA PURA 14,95 7,475 1 978-84-674-6212-8 AMERICAN SPLENDOR: OTRO DIA MAS 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-3851-2 -

Soteriology in Edmund Spenser's 'The Faerie Queene'

SOTERIOLOGY IN EDMUND SPENSER’S THE FAERIE QUEENE by STUART ANTHONY HART A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English Literature School of English, Drama and American and Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis demonstrates the extent to which the sixteenth-century allegorical epic poem, The Faerie Queene, engages with early modern theories of salvation. Much has been written about Spenser’s consideration of theological ideas in Book I and this has prompted scholars to speculate about the poet’s own doctrinal inclinations. However, little has been written about the ways in which the remaining books in the poem also explore Christian ideas of atonement, grace and damnation. This study advances Spenserian scholarship by stressing the soteriological dimension of books II, III, IV and VI. It considers how the poem’s doctrinal ambiguity would have meant that Spenser’s readers would have been able to interpret the poem in terms of the different schools of thought on the conditionality, or otherwise, of election and reprobation. -

NVS 1-1 A-Williamson

“The Dead Man Touch’d Me From the Past”: Reading as Mourning, Mourning as Reading in A. S. Byatt’s ‘The Conjugial Angel’ Andrew Williamson (The University of Queensland, Australia) Abstract: At the centre of nearly every A. S. Byatt novel is another text, often Victorian in origin, the presence of which stresses her demand for an engagement with, and a reconsideration of, past works within contemporary literature. In conversing with the dead in this way, Byatt, in her own, consciously experimental, work, illustrates what she has elsewhere called “the curiously symbiotic relationship between old realism and new experiment.” This symbiotic relationship demands further exploration within Possession (1990) and Angels and Insects (1992), as these works resurrect the Victorian period. This paper examines the recurring motif of the séance in each novel, a motif that, I argue, metaphorically correlates spiritualism and the acts of reading and writing. Byatt’s literary resurrection creates a space in which received ideas about Victorian literature can be reconsidered and rethought to give them a new critical life. In a wider sense, Byatt is examining precisely what it means for a writer and their work to exist in the shadow of the ‘afterlife’ of prior texts. Keywords: A. S. Byatt, ‘The Conjugial Angel’, mourning, neo-Victorian novel, Possession , reading, séance, spiritualism, symbiosis. ***** Nature herself occasionally quarters an inconvenient parasite on an animal towards whom she has otherwise no ill-will. What then? We admire her care for the parasite. (George Eliot 1979: 77) Towards the end of A. S. Byatt’s Possession (1990), a group of academics is gathered around an unread letter recently exhumed from the grave of a pre-eminent Victorian poet, the fictional Randolph Henry Ash. -

23 League in New York Before They Were Purchased by Granville

is identical to a photograph taken in 1866 (fig. 12), which includes sev- eral men and a rowboat in the fore- ground. From this we might assume that Eastman, and perhaps Chapman, may have consulted a wartime pho- tograph. His antebellum Sumter is highly idealized, drawn perhaps from an as-yet unidentified print, or extrapolated from maps and plans of the fort—child’s play for a master topographer like Eastman. Coastal Defenses The forts painted by Eastman had once been the state of the art, before rifled artillery rendered masonry Fig. 11. Seth Eastman, Fort Sumter, South Carolina, After the War, 1870–1875. obsolete, as in the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861 and the capture of Fort Pulaski one year later. By 1867, when the construction of new Third System fortifications ceased, more than 40 citadels defended Amer- ican coastal waters.12 Most of East- man’s forts were constructed under the Third System, but few of them saw action during the Civil War. A number served as military prisons. As commandant of Fort Mifflin on the Delaware River from November 1864 to August 1865, Col. Eastman would have visited Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island, located in the river channel between Wilmington and New Castle, Delaware. Channel-dredging had dumped tons of spoil at the northern end of the island, land upon which a miserable prison-pen housed enlisted Confederate pris- oners of war. Their officers were Fig. 12. It appears that Eastman used this George N. Barnard photograph, Fort quartered within the fort in relative Sumter in April, 1865, as the source for his painting. -

Carolyn G. Heilbrun I Beautiful Shadow: a Life of Patricia Highsmith by Andrew Wilson PRODUCTION EDITOR: Amanda Nash [email protected] 7 Marie J

The Women’s Review of Books Vol. XXI, No. 3 December 2003 74035 $4.00 I In This Issue I Political organizers are serious, while the patrons of drag bars and cabarets just wanna have fun, right? Julie Abraham challenges the cate- gories in her review of Wide Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco. Cover story D I Before she died, Carolyn Heilbrun contributed a final essay to the Women’s Review—a discussion of Beautiful Shadow: A Biography of Patricia Highsmith. The piece expresses Heilbrun’s lifelong inter- est in writing women’s lives, and we publish it with pride and sadness, along with a tribute to the late scholar and mystery novelist. p. 4 Kay Scott (right) and tourists at Mona's 440, a drag bar, c. 1945. From Wide Open Town. I When characters have names like Heed the Night, L, and Celestial, we could be nowhere but in a Toni Morrison novel. Despite Tales of the city its title, Love, her latest, is more by Julie Abraham philosophical exploration than pas- Wide Open Town: A History of Queer San Francisco to 1965 by Nan Alamilla Boyd. sionate romance, says reviewer Deborah E. McDowell. p. 8 Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003, 319 pp., $27.50 hardcover. I I The important but little-known n Wide Open Town, Nan Alamilla Boyd so much lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender feminist Lucy Stone, who stumped presents queer San Francisco as the scholarship, have served as key points of the country for women’s suffrage, Iproduct of a town “wide open” to all reference in US queer studies over the past forms of pleasure, all forms of money-mak- two decades. -

Melchizedek Or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by JC Grumbine

Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine Published in 1919 "I will utter things which have been kept secret from the foundation of the world". Matthew 13: 35 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Lecture 1 Who is Melchizedek? Biblical History. His Office and His Order The Secret Doctrines of the Order. Its Myths, Mysteries, Lecture 2 Symbolisms, Canons, Philosophy The Secret Doctrine on Four Planes of Expression and Lecture 3 Manifestation Lecture 4 The Christ Psychology and Christian Mysticism Lecture 5 The Key - How Applied. Divine Realization and Illumination Page 1 Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine INTRODUCTION The Bible has been regarded as a sealed book, its mysteries impenetrable, its knowledge unfathomable, its key lost. Even its miracles have been so excluded from scientific research as to be invested with a supernaturalism which forever separated them from the possibility of human understanding and rational interpretation. In the midst of these revolutionary times, it is not strange that theology and institutional Christianity should feel the foundations of their authority slipping from them, and a new, broader and more spiritual thought of man and God taking their places. All this is a part of the general awakening of mankind and has not come about in a day or a year. It grew. It is still growing, because the soul is eternal and justifies and vindicates its own unfoldment. Some see in this new birth of man that annihilation of church and state, but others who are more informed and illumined, realized that the chaff and dross of error are being separated from the wheat and gold of truth and that only the best, and that which is for the highest good of mankind will remain. -

Directory of Homoeopathic Physicians in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas

A DELICIOUS Highly Nutritious' 1 BEVERAGE. Phillips Digestible Goeoa Easily Digested, set adapts Mich- 2288. This is entirely different from any other preparation of Chocolate or Cocoa. of full ana. Box the diseases” ILL. and graduated,hospitalsMich. one, ' DIRECTORY in new or /YRJ ubinaky upon both Arbor, cA — OF— and CHICAGO, in circular,and Ana Volumes Truss & newbeing Arbor, t'o., Y|omo£op&lhi(R- two venebeal AVENUE, a on is Ann Truss $ fRY§I(RIAfT§) pressure of This WABASH The men Imperial — — Therapeutics,” Trial. IN “monograph 1636 and Spring. Egan’s Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, the medical and of best Clinical AGENT, the others. Nebraska, and Ohio. cakds, strengthall many Boyne’s Examination as by are for 1885-6.- 'you medica VEEDER, well Used F. as circulars send our Published, by H. A. MUMAW, Nappanee, form,cured. On materia Profession of get will and I rate. Medicalsize Mich. low thein children TABLET TRITURATES very to all Arbor, PREPARED BY a :n"E22:t’ at varying E DAYS. Fbee NearlyAnn FRASER & CO., NEW YORK CITY. Pad, T:E3 works Sent night.Block, THIRTY Spring TABLET TRITURATES TABLET TRITURATES these russ and From TRITURATIONS. From TINCTURES. T day obtain Hamilton These are the finest and most carefully made an Spiral Triturations, moulded into elegant and to convenientform bedside and office dispensing. a for The Tincture Triturates contain one-half, Worn one or two minims of the Mother Tincture, or officinal Tincture of the drug it represents. Imperial The Tablets are soluble and exact, and a trial of their medical value together with their great havingbody. -

Historic-Register-OPA-Addresses.Pdf

Philadelphia Historical Commission Philadelphia Register of Historic Places As of January 6, 2020 Address Desig Date 1 Desig Date 2 District District Date Historic Name Date 1 ACADEMY CIR 6/26/1956 US Naval Home 930 ADAMS AVE 8/9/2000 Greenwood Knights of Pythias Cemetery 1548 ADAMS AVE 6/14/2013 Leech House; Worrell/Winter House 1728 517 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 519 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 600-02 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 2013 601 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 603 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 604 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 605-11 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 606 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 608 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 610 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 612-14 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 613 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 615 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 616-18 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 617 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 619 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 629 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 631 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 1970 635 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 636 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 637 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 638 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 639 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 640 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 641 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 642 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 643 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 703 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 708 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 710 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 712 ADDISON ST Society Hill 3/10/1999 714 ADDISON ST Society Hill