Tourism and Sustainability in Brazil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Currency and Coin Management

The George Washington University WASHINGTON DC IBI - INSTITUTE OF BRAZILIAN BUSINESS AND PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ISSUES The Minerva Program Fall 2004 CURRENCY AND COIN MANAGEMENT: A COMPARISON OF AMERICAN AND BRAZILIAN MODELS Author: Francisco José Baptista Campos Advisor: Prof. William Handorf Washington, DC – December 2004 AKNOWLEDGMENTS ? to Dr. Gilberto Paim and the Instituto Cultural Minerva for the opportunity to participate in the Minerva Program; ? to the Central Bank of Brazil for having allowed my participation; ? to Professor James Ferrer Jr., Ph.D., and his staff, for supporting me at the several events of this Program; ? to Professor William Handorf, Ph.D., for the suggestions and advices on this paper; ? to Mr. José dos Santos Barbosa, Head of the Currency Management Department, and other Central Bank of Brazil officials, for the information on Brazilian currency and coin management; ? to the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and, in particular, to Mr. William Tignanelli and Miss Amy L. Eschman, who provided me precious information about US currency and coin management; ? to Mr. Peter Roehrich, GWU undergraduate finance student, for sharing data about US crrency and coin management; and, ? to Professor César Augusto Vieira de Queiroz, Ph.D., and his family, for their hospitality during my stay in Washington, DC. 2 ? TABLE OF CONTENTS I – Introduction 1.1. Objectives of this paper 1.2. A brief view of US and Brazilian currency and coin II – The currency and coin service structures in the USA and in Brazil 2.1. The US currency management structure 2.1.1. The legal basis 2.1.2. The Federal Reserve (Fed) and the Reserve Banks 2.1.3. -

Economic Impacts of Tourism in Protected Areas of Brazil

Journal of Sustainable Tourism ISSN: 0966-9582 (Print) 1747-7646 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsus20 Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souza, Brijesh Thapa, Camila Gonçalves de Oliveira Rodrigues & Denise Imori To cite this article: Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souza, Brijesh Thapa, Camila Gonçalves de Oliveira Rodrigues & Denise Imori (2018): Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 Published online: 02 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rsus20 Download by: [Thiago Souza] Date: 03 January 2018, At: 03:26 JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE TOURISM, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633 Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil Thiago do Val Simardi Beraldo Souzaa, Brijesh Thapa b, Camila Goncalves¸ de Oliveira Rodriguesc and Denise Imorid aChico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation and School of Natural Resources and Environment, EQSW, Complexo Administrativo, Brazil & University of Florida, Brasilia, DF, Brazil; bDepartment of Tourism, Recreation & Sport Management, FLG, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA; cDepartment of Business and Tourism, Rua Marquesa de Santos, Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil; dDepartment of Economy, Rua Comendador Miguel Calfat, University of S~ao Paulo, S~ao Paulo, SP, Brazil ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Protected areas (PAs) are globally considered as a key strategy for Received 31 October 2016 biodiversity conservation and provision of ecosystem services. -

Developing Nature-Based Tourism in Africa's State Protected Areas

BUILDING A WILDLIFE ECONOMY Working Paper 1: Developing Nature-Based Tourism in Africa’s State Protected Areas BUILDING A WILDLIFE ECONOMY 1 THIS DOCUMENT This working paper is the first in a series produced by UN ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME Space for Giants and the United Nations Environment The United Nations Environment Programme (UN Programme (UN Environment) entitled ‘Building a Environment) is the leading global environmental wildlife economy’. The series has been commissioned authority that sets the global environmental agenda, to inform a framework for the African Union and its promotes the coherent implementation of the member nations for the optimum use of wildlife to environmental dimension of sustainable development diversify and expand their economies, strengthen the within the United Nations system, and serves as an livelihoods of their citizens, and achieve ecological authoritative advocate for the global environment. resilience in the face of pressing modern social and Our mission is to provide leadership and encourage environmental challenges. Conservation Capital were the partnership in caring for the environment by inspiring, lead technical authors of this Working Paper. informing, and enabling nations and peoples to improve their quality of life without compromising that of future generations. ABOUT US FUNDING & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This Working Paper was funded by UN Environment and SPACE FOR GIANTS Space for Giants. The authors are Conservation Capital Space for Giants is an international conservation charity (lead technical author) and Space for Giants.. The authors that protects Africa’s elephants and their habitats while would like to acknowledge and thank the following for demonstrating the ecological and economic value their technical guidance and input: James Vause, Nina both can bring. -

Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 (Pdf)

Agricultural Marketing Service July 2019 Soybean Transportation Guide: BRAZIL 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Marketing and Regulatory Programs Agricultural Marketing Service Transportation and Marketing Program July 2019 Author: Delmy L. Salin, USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service Graphic Designer: Jessica E. Ladd, USDA, Agricultural Marketing Service Preferred Citation Salin, Delmy. Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018. July 2019. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. Web. <http://dx.doi.org/10.9752/TS048.07-2019> USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender. 2 Contents Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 . 4 General Information. 7 2018 Summary . 8 Transportation Infrastructure. 25 Transportation Indicators. 28 Soybean Production . 38 Exports. 40 Exports to China . 45 Transportation Modes . 54 Reference Material. 66 Photo Credits. 75 3 Soybean Transportation Guide: Brazil 2018 Executive Summary The Soybean Transportation Guide is a visual snapshot of Brazilian soybean transportation in 2018. It provides data on the cost of shipping soybeans, via highways and ocean, to Shanghai, China, and Hamburg, Germany. It also includes information about soybean production, exports, railways, ports, and infrastructural developments. Brazil is one of the most important U.S. competitors in the world oilseed market. Brazil’s competitiveness in the world market depends largely on its transportation infrastructure, both production and transportation cost, increases in planted area, and productivity. Brazilian and U.S. producers use the same advanced production and technological methods, making their soybeans relative substitutes. U.S soybean competitiveness worldwide rests upon critical factors such as transportation costs and infrastructure improvements. Brazil is gaining a cost advantage. However, the United States retains a significant share of global soybean exports. -

Ecotourism Outlook 2019 Prepared for the 2019 Outlook Marketing Forum

Ecotourism Outlook 2019 Prepared for the 2019 Outlook Marketing Forum Prepared by: Qwynne Lackey, Leah Joyner & Dr. Kelly Bricker, Professor University of Utah Ecotourism and Green Economy What is Ecotourism? Ecotourism is a subsector of the sustainable tourism industry that emphasizes social, environmental, and economic sustainability. When implemented properly, ecotourism exemplifies the benefits of responsible tourism development and management. TIES announced that it had updated its definition of ecotourism in 2015. This revised definition is more inclusive, highlights interpretation as a pillar of ecotourism, and is less ambiguous than the version adopted 25 years prior. In 2018, no new alterations were made to this highly cited definition which describes ecotourism as: “Responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people and involves interpretation and education.”1 This definition clearly outlines the key components of ecotourism: conservation, communities, and sustainable travel. Ecotourism represents a set of principles that have been successfully implemented in various communities and supported by extensive industry practice and academic research. Twenty-eight years since TIES was started, it is important to re-visit three principles found in TIES literature – that ecotourism: • is NON-CONSUMPTIVE / NON-EXTRACTIVE • creates an ecological CONSCIENCE • holds ECO-CENTRIC values and ethics in relation to nature TIES considers non-consumptive and non-extractive use of resources for and by tourists and minimized impacts to the environment and people as major characteristics of authentic ecotourism. What are the Principles of Ecotourism? Since 1990, when TIES framework for ecotourism principles was established, we have learned more about the tourism industry through scientific and design-related research and are also better informed about environmental degradation and impacts on local cultures and non-human species. -

Download This PDF File

53799 Brazilian Journal of Development Fungal colonization on body surfaces of dead south American Sea lions on sandy beaches, and an evaluation of risk of contamination to humans at southern Brazil Colonização fúngica em superfícies corporais de leões marinhos mortos da América do Sul em praias arenosas, e uma avaliação do risco de contaminação para os seres humanos no sul do Brasil DOI:10.34117/bjdv6n7-866 Recebimento dos originais:08/06/2020 Aceitação para publicação:31/ 07/2020 Eliane Machado Pereira Doutora em ciências pela Universidade Federal de Pelotas Instituição: UFPEL Endereço: Rua Sr. Ary Rodrigues de Alcântara 94, Pelotas,RS/ Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Josiara Furtado Mendes Doutora em ciências pela Universidade Federal de Pelotas Instituição: UFPEL Endereço:Rua dos Jacarandás, 647, Capão do Leão, RS, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Joanna Vargas Zillig Echenique Mestre em Sanidade Animal pela Universidade Federal de Pelotas Residente - Setor de Patologia Veterinária - SPV-UFRGS Endereço:Av. Bento Gonçalves, 9090 - Agronomia, Porto Alegre - RS CEP: 90540-000 CEL: (53) 981146941 E-mail:[email protected] Daniela Isabel Brayer Pereira Doutora em Ciências Veterinárias pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Instituição: Universidade Federal de Pelotas Endereço: Instituto de Biologia, Depto. de Microbiologia e Parasitologia, Campus Capão do Leão, IB prédio 18. CEP 96160000 E-mail: [email protected] Ana Luisa Schifino Valente Doutora em Medicina e Cirurgia Animal pela Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona Instituição: Universidade Federal de Pelotas Endereço: Instituto de Biologia, Depto. de Morfologia, Campus Capão do Leão, IB prédio 24. CEP 96010-900 E-mail: [email protected] Braz. -

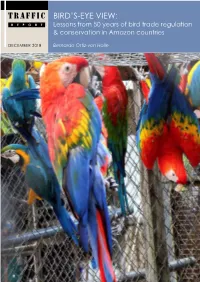

TRAFFIC Bird’S-Eye View: REPORT Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in Amazon Countries

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal

Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Ana Nath Baral Lincoln University 2013 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science (Parks, Tourism and Ecology) Abstract Impacts of Wildlife Tourism on Poaching of Greater One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) in Chitwan National Park, Nepal by Ana Nath Baral Chitwan National Park (CNP) is one of the most important global destinations to view wildlife, particularly rhinoceros. The total number of wildlife tourists visiting the park has increased from 836 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1974/75 to 172,112 in FY 2011/12. But the rhinoceros, the main attraction for the tourists, is seriously threatened by poaching for its horn (CNP, 2012). Thus, the study of the relationship between wildlife tourism and rhinoceros poaching is essential for the management of tourism and control of the poaching. This research identifies the impacts of tourism on the poaching. It documents the relationships among key indicators of tourism and poaching in CNP. It further interprets the identified relationships through the understandings of local wildlife tourism stakeholders. Finally, it suggests future research and policy, and management recommendations for better management of tourism and control of poaching. Information was collected using both quantitative and qualitative research approaches. Data were collected focussing on the indicators of the research hypotheses which link tourism and poaching. -

The Relevance of the Cerrado's Water

THE RELEVANCE OF THE CERRADO’S WATER RESOURCES TO THE BRAZILIAN DEVELOPMENT Jorge Enoch Furquim Werneck Lima1; Euzebio Medrado da Silva1; Eduardo Cyrino Oliveira-Filho1; Eder de Souza Martins1; Adriana Reatto1; Vinicius Bof Bufon1 1 Embrapa Cerrados, BR 020, km 18, Planaltina, Federal District, Brazil, 70670-305. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Cerrado (Brazilian savanna) is the second largest Brazilian biome (204 million hectares) and due to its location in the Brazilian Central Plateau it plays an important role in terms of water production and distribution throughout the country. Eight of the twelve Brazilian hydrographic regions receive water from this Biome. It contributes to more than 90% of the discharge of the São Francisco River, 50% of the Paraná River, and 70% of the Tocantins River. Therefore, the Cerrado is a strategic region for the national hydropower sector, being responsible for more than 50% of the Brazilian hydroelectricity production. Furthermore, it has an outstanding relevance in the national agricultural scenery. Despite of the relatively abundance of water in most of the region, water conflicts are beginning to arise in some areas. The objective of this paper is to discuss the economical and ecological relevance of the water resources of the Cerrado. Key-words: Brazilian savanna; water management; water conflicts. INTRODUCTION The Cerrado is the second largest Brazilian biome in extension, with about 204 million hectares, occupying 24% of the national territory approximately. Its largest portion is located within the Brazilian Central Plateau which consists of higher altitude areas in the central part of the country. -

ECONOMIC IMPACT of DENGUE in TOURISM in BRAZIL Alvaro Mitsunori Nishikawa1, Otávio Clark1, Victoria Genovez2, Amanda Pinho2, Laure Durand3

ECONOMIC IMPACT OF DENGUE IN TOURISM IN BRAZIL Alvaro Mitsunori Nishikawa1, Otávio Clark1, Victoria Genovez2, Amanda Pinho2, Laure Durand3 1Kantar Health _ Evidências, São Paulo, Brazil; 2Sanofi Pasteur, São Paulo, Brazil;3 Sanofi Pasteur, Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico PIN29 2013 was considered the base year, since i) a dengue outbreak have occurred in the country, ii) there are data on tourism and epidemiology of the disease, iii) any unusual international events occurred this year. Introduction Methodology Dengue is an endemic disease that is rapidly growing worldwide. A recent study estimates 2013 was considered the base year, since i) a dengue outbreak have occurred in the that 390 million annual infections occur around the world. country, ii) there are data on tourism and epidemiology of the disease, iii) any unusual Dengue has become one of the major diseases affecting the Brazilian public health.1 international events occurred this year. The rising incidence of the disease and its unpredictable outbreaks result in a significant economic impact in the health system and society. 18 Literature review: Published articles, grey and non-scientific In Brazil, tourism revenue is an important part of the GDP, and the Ministry of Health has Step 1 already recognized the importance of dengue on tourism revenues.2 literature focusing on the impact of dengue on tourism. Estimation on tourism: Number of international tourists arrivals Step 2 and national tourists transits; Expenditure from national and international tourists in Brazil. Calculation: The most conservative impact of dengue on tourism, Step 3 from literature review, was applied to the Brazilian tourism for the Objective most epidemic months (Jan-May).17 Sensitivity Analysis: Deterministic sensitivity analysis on the Step 4 To estimate the economic impact of a dengue outbreak (incidence ≥300 dengue cases most uncertain parameters. -

A Study on the Geographical Distribution of Brazil's Prestigious

Figueira Filho et al. Journal of Internet Services and Applications (2015) 6:17 DOI 10.1186/s13174-015-0032-6 RESEARCH Open Access A study on the geographical distribution of Brazil’s prestigious software developers Fernando Figueira Filho1*, Marcelo Gattermann Perin2, Christoph Treude1, Sabrina Marczak3, Leandro Melo1, Igor Marques da Silva1 and Lucas Bibiano dos Santos1 Abstract Brazil is an emerging economy with many IT initiatives from public and private sectors. To evaluate the progress of such initiatives, we study the geographical distribution of software developers in Brazil, in particular which of the Brazilian states succeed the most in attracting and nurturing them. We compare the prestige of developers with socio-economic data and find that (i) prestigious developers tend to be located in the most economically developed regions of Brazil, (ii) they are likely to follow others in the same state they are located in, (iii) they are likely to follow other prestigious developers, and (iv) they tend to follow more people. We discuss the implications of those findings for the development of the Brazilian software industry. Keywords: Collaborative software development; Software engineering; Social network analysis; Brazil 1 Introduction growing at fast rates, the Brazilian software industry still Information Technology (IT) has been playing a major lags behind in export revenue and most of its produc- role in rapidly growing economies and emerging mar- tion is consumed in the domestic market. To improve kets such as the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and Brazil’s global competitiveness, recent policies from the China), Mexico, Malaysia, Indonesia, and others [32]. The Brazilian government have aimed at fostering innovation development of information and communication tech- with public incentives, which include increasing funds for nologies has long been referred to as a “strategic tool” and R&D projects and providing tax breaks for key indus- a pre-requisite for economic growth and social develop- trial sectors such as IT, biotechnology, and energy. -

Public Urban Transport Systems: the Case of Curitiba

Sustainable public urban transport systems: The case of Curitiba Author: Andrea Cinquina Lund University International Masters Program in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Sciences LUMES 2006/08 MESM01 Thesis Course [email protected] Supervisor: Prof. Bengt Holmberg Traffic Planning, LHT Lund University Andrea Cinquina Lumes Thesis 2008 Abstract This paper describes the present urban public transportation in the city of Curitiba, Brazil. The city was chosen for this research because of its urban public transport system, which had a major role in urban planning development; this consists of an integrated network of busses, developed in combination with land use, population density and road hierarchy, as a consequence of the Master Plan implemented by the city in the late 60s. The sustainability of the system was analysed, using as the main framework, the United Nations Habitat Agenda recommendations on sustainable transport and applying these criteria to the public transport system of Curitiba, making use of available literature, interviews and observations. From the analyses of the system, it was evident that it achieved positive indicators regarding its sustainability in the criteria of accessibility, economical feasibility and coordination of land use and transport system. However, negative indicators were also evident, that leads to the conclusion that it is not a sustainable system. These aspects were in the criteria of intermodal transportation, disincentives for private motorization traffic and the use of diesel fuel.