SHEMZA.DIGITAL: Participatory Art As a Catalyst for Social Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Candidates Who Applied for Nursery Admissions 2013-14 Reg

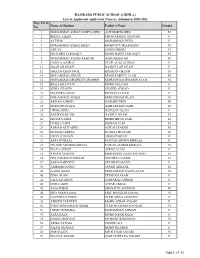

HAMDARD PRIMARY SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of candidates who applied for Nursery admissions 2013-14 Reg. Remarks of the verification Form Name of Student Father's Name deparmtment or Admission Cases Total Single Parent No. Gender Siblings Siblings Alumini Alumini Deparmtment Muslims Muslims Distance Transfer 1 FARHAN IQBAL QUAISER IQBAL M 25 - - - - 20 45 2 KASHAAN KHAN ADIB KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 3 SAMAN KHAN MUNSHAD KHAN F 25 - - - - 20 45 4 ZUNAIRA SHAKEEL SHAKEEL AHMAD F 25 25 - - - 20 70 5 MUSTAFA JAMAL KOSAR JAMAL KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 6 TABSUM FATMA MD. NAUSHAD F 25 - - - - 20 45 7 NUMAIR KHAN ASRAR HUSSAIN KHAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 8 SHIPRA BEHURA SRIKANT KUMAR BEHURA F 25 - 10 - - - 35 9 SAMAKSHYA BEHURA SRIKANT KUMAR BEHURA M 25 - - - - - 25 Proof of Single Parent Not Given 10 HITEN BEHURA HEMENT BEHURA M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof 12 MOHAMMAD SARHAN MOHAMMAD SUFIYAN M 25 - - - - 20 45 13 MOHD. HABEEB JAMIL QAISAR JAMAL QURAISHI M 25 - - - - 20 45 14 GHULAM WALI IMAM AZHAR IMAM M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof 15 SAYED MOHAMMAD ISMAEEL SAYED RIZWANUL HAQUE M 25 - - - - 20 45 16 MOHD. AQIB MOHD. ASIF M 25 - - - - 20 45 17 ILMA ZAFAR HEDAYAT ULLAH ZAFAR F 25 - - - - 20 45 23 KULSUM JAVED SAFDAR JAVED F 25 - - - - 20 45 24 RUBAB FATIMA MOHAMMAD KHURSHEED ALAM F 25 - - - - 20 45 26 MUHAMMAD ABAAN MUHAMMAD ARIF M 25 - - - - 20 45 Transfer Not Applicable 27 MD. SHAFAI MD. FIROJ ALAM M 25 - - - - 20 45 28 ARHAM RAHMAN TANWIR ALAM M R R R R R R R Invalid Address Proof There are total 124 applicants who secured 70 points against 110 seats for nursery for which a draw will be held on 25.02.2013 (Monday) at 12 noon to finalise the selected list of the candidates for admission in Nursery HAMDARD PRIMARY SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of candidates who applied for Nursery admissions 2013-14 Reg. -

Pakistan Ka Matlab Kya?

Pakistan Ka Matlab Kya? (What does Pakistan Mean?) Decolonizing State and Society in 1960s and 1970s in Pakistan A thesis submitted by Neelum Sohail In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2015 ADVISERS: Ayesha Jalal Kris Manjapra ii ABSTRACT This thesis studies the 1960s and 1970s in Pakistan. It is argued here that this period saW a concerted effort across the political spectrum to bring the nation into closer proXimity With the state. There Was a dominant move in the late 1960s and early 1970s towards decolonizing state with the purpose of transforming neocolonial state institutions in order to make them representative, egalitarian and democratic. Students, intellectuals, peasants, industrial labor and leftists participated in a series of disturbances and rebellion that reached a climaX in Ayub Khan’s removal from poWer and the rise of the PPP to poWer in West Pakistan. Popular decolonization narratives are discussed here through an intellectual portrait of Bhutto, a discussion of Habib Jalib's poetry and an exploration of neWspaper articles, magazines, plays and an Urdu film from the time period. iii Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER 1 CARVING OUT A PATH TOWARDS DEMOCRACY .................................................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 STUDENTS, INTELLECTUALS AND WORKERS .................................................................... -

Part II: Unveiling the Unspoken

LZK-8 SOUTH ASIA Leena Z. Khan is an Institute Fellow studying the intersection of culture, cus- ICWA toms, law and women’s lives in Pakistan. Part II LETTERS Unveiling the Unspoken By Leena Z. Khan Since 1925 the Institute of Current World Affairs (the Crane- MARCH, 2002 Rogers Foundation) has provided North Nazimabad, Defence, Bath Island — Karachi, Pakistan long-term fellowships to enable outstanding young professionals After beginning my study on women artists in Karachi I soon realized that to live outside the United States one newsletter would not give the subject matter justice. It was a difficult choice selecting which women artists to write about. I came across a number of talented and write about international women artists in the city, many who are still struggling to make a name for them- areas and issues. An exempt selves and legitimize their career-choice to their families and peers. For this news- operating foundation endowed by letter I chose to write on two notable and seasoned Karachi-based artists belong- the late Charles R. Crane, the ing to the first generation of the country’s art institutions — Meher Afroz and Institute is also supported by Riffat Alvi. The work of both women is remarkable because they have an informed contributions from like-minded and strong vision of what the society in which they live in could be. Although individuals and foundations. visually their paintings are very different, these two women share much in com- mon; Both have earned approbation in art circles throughout Pakistan and abroad; their respective paintings can be interpreted as a commentary on the social and TRUSTEES cultural landscape of the country; both have strong convictions and can criticize Joseph Battat the society in which they live as well as embrace it; both artists are deeply spiri- Mary Lynne Bird tual and have an introspective relationship toward their faith; both women are in Steven Butler their late 50s and opted not to marry. -

Reg. Form No. Name of Student Father's Name Gender List Of

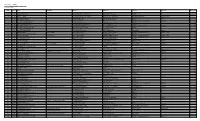

HAMDARD PUBLIC SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of Applicants applied for Nursery Admission 2020-2021 Reg. Form No. Name of Student Father's Name Gender 1 MOHAMMAD ASHAZ MOHTASHIM ASIF MOHTASHIM M 2 REEDA AZEEN MD SHARIQUE HASNAIN F 3 AYESHA MOHAMMAD DEEN F 4 MOHAMMAD ASHAZ KHAN MOHD NOUSHAB KHAN M 5 ADYAN SOMIN SHEKH M 7 MD HARIS FAROOQUI MOHD RAHIS FAROOQUI M 8 MUHAMMAD AQDAS AKHTAR ASIM AKHATAR M 9 HAMYA ASHRAF SYED AYAZ ASHRAF F 11 NAAILAH GHAZI NASRULLAH GHAZI F 12 ISHAAN KHANTWAL KRISHAN CHAND M 14 MOHAMMAD ARBAB MOHD PARVEZ ALAM M 16 MOHAMMAD SHAHIQUE SHABBIR MOHAMMAD SHABBIR ALAM M 18 RIFZA KHATOON MOHD GULFAM F 19 SIDRA SHAHID SHAHID AHMAD F 20 MAAHIRA JAMAL MUSTAFA JAMAL F 21 MOHAMMAD ADEEB MOHAMMAD ISLAM M 22 ARMAN AHMED NAWABUDDIN M 23 MOHD MUSTAFA AQIB MIFTAH JAFRI M 24 UMME SIDRA RAHEEM ULLAH F 25 ZAKWAN ISLAM NAJMUL ISLAM M 26 MUSTFA SAIFI MOHD IRFAN SAIFI M 27 HUMZA SAIFI RIZWAN SAIFI M 29 AHMAD ALI FARIDI ASIF ALI FARIDI M 30 HUSSAIN ABBAS NUSRAT HUSSAIN M 31 ANAYAH KHAN ARSHAD KHAN F 32 ARFA KHWAJA FAUZAN AHMED KHWAJA F 33 MUADH AHMED KHWAJA FAINAN AHMED KHWAJA M 34 INAYA AFROZ AFROZ ALAM F 35 AFHAM MASLEH MOHAMMED MASLEHUDDIN M 36 MUHAMMAD HAMMAD GHUFRAN JALEEL M 37 AISHA PARVEEN GHUFRAN JALEEL F 38 TAMEEM JAWED JAWED AKHTAR M 39 AASIM AZAM MOHAMMAD NAZIM AZAM M 40 IZMA ALAM ZEESHAN ALAM F 41 AIZA ALI KHAN SARFARAZ AHMAD F 42 HUDA ABIDI AFSAR ABBAS F 43 ANAS KHAN SHANAULLAH KHAN M 44 SHIVANSH SAMAL SHIV SHANKAR SAMAL M 47 ALVEERA FATIMA SYED AJMAL HUSSAIN F 48 AFREEN PARVEEN MOHD AZHAR ANSARI F 52 SYED MOHAMMAD ORAIB SYED MOHAMMAD OQAIS M 53 UMME HUMAIRA MOHAMMAD AHMAD F 54 AZRA RAZA MOHD NASIR RAZA F 55 HAMZA REHMAN MUJEEB UR REHMAN M 56 ARIBA FATIMA SHAHID ALI F 57 AIZAH DILSHAD MOHD DILSHAD F 58 MOHD ZAIN MD SUHAIB ANSARI M 59 INAAYA ANSARI ZAKI MURTAZA ANSARI F Page 1 of 22 HAMDARD PUBLIC SCHOOL (OKHLA) List of Applicants applied for Nursery Admission 2020-2021 Reg. -

ART of PAKISTAN Wednesday May 24 2017

ART OF PAKISTAN Wednesday May 24 2017 ART OF PAKISTAN Wednesday 24 May 2017 at 2pm 101 New Bond Street, London VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES Friday 19 May 2017 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Tahmina Ghaffar Monday to Friday 8:30am to 6pm 11am to 3pm +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8382 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Sunday 21 May 2017 To bid via the internet please [email protected] 11am to 3pm visit bonhams.com As a courtesy to intending Monday 22 May 2017 PRESS ENQUIRIES bidders, Bonhams will provide a 9am to 4.30pm Please note that bids should be written Indication of the physical [email protected] Tuesday 23 May 2017 submitted no later than 4pm condition of lots in this sale if a 9am to 1.30pm on the day prior to the sale. request is received up to 24 Wednesday 23 May 2017 New bidders must also provide hours before the auction starts. 9am to 12pm proof of identity when submitting This written Indication is issued bids. Failure to do this may result subject to Clause 3 of the Notice in your bid not being processed. to Bidders. SALE NUMBER Telephone bidding can only be ILLUSTRATIONS 24249 accepted on lots with a Front cover: lot 18 low-estimate in excess of £1000. Back cover: lot 19 CATALOGUE Inside Front cover: lot 25 £30.00 Live online bidding is available Inside Frontispiece: lot 14 for this sale Inside Back cover: lot 27 Please email [email protected] with ‘live bidding’ in the subject IMPORTANT INFORMATION line 48 hours before the auction The United States Government to register for this service has banned the import of ivory into the USA. -

Dividend -2013

NCC BANK LIMITED Dividend List for Bank AGM 2013 Warrant # Name of Sharholders Net Payable (Tk.) DW0096367 NASIR UDDIN KHAN 2,238.75 DW0096368 SHYMAL DAS 404.85 DW0096369 MD.FAIZULLAH 844.50 DW0096370 JAHEDA ISLAM 118.80 DW0096371 MD. MATINUR RASHID CHOWDHURY 166.20 DW0096375 MD. NURUL ISLAM 9,329.56 DW0096379 MD. SIRAJUL ISLAM 2,470.80 DW0096380 MOHAMMED FERDOUS KHAN 651.15 DW0096381 MD DIDARUL ALAM CHOWDHURY 2,631.46 DW0096384 KAZI RAFIQUL HASSAN 390.61 DW0096388 M. A. HALIM 95.85 DW0096389 MD. TAUFIQUL ISLAM 184.65 DW0096390 AHMED SHARIF 95.85 DW0096392 MR. KHAN TARIQUL ISLAM 390.61 DW0096394 MD. FARID AHMED PATWARY 1,061.26 DW0096398 MR. DR. ABDUL WAHED 2,296.95 DW0096399 MD. ABUL BASHAR 153.30 DW0096400 GOOL AFROZA DILRUBA 84.00 DW0096401 NURUL HOQUE 223.35 DW0096402 SHAH ALAM BABU 522.60 DW0096403 MD. ABDUR ROUF 24.46 DW0096404 JAHANGIR IQBAL 4,169.56 DW0096405 MR. MAMUNUR RAHMAN 2,143.36 DW0096406 MD. MAHAMUDUL HASAIN 95.85 DW0096407 DR MD KHORSHED ALAM TALUKDER 2,005.06 DW0096411 MR. RUHUL KUDDUS. 171.16 DW0096412 MR. TAPAN JYOTI SAHA 87.16 DW0096419 ASOKE KUMAR SAHA 113.25 DW0096420 BASHIR AHMED 173.85 DW0096421 MD. SAIFUL ISLAM 113.25 DW0096422 MD. JAHANGIR ALAM 356.40 DW0096423 GOLAM RABBANI MD. MASUD RANA 16.81 DW0096424 GOLAM RABBANI MD. MASUD RANA 16.81 DW0096425 NOYAN CHAKMA 16.81 DW0096426 NOYAN CHAKMA 16.81 DW0096427 MD. SHAMSUL ALAM DEWAN 16.81 DW0096428 MD. FARID HOSSAIN 1,890.00 DW0096433 JHAYA CHAKMA 2.10 DW0096434 JHAYA CHAKMA 15.00 DW0096435 MD. -

Roll No Name of the Student Eng/ Mar / His/ Soc/Geo

RAMNIRANJAN JHUNJHUNWALA COLLEGE GHATKOPAR (W) MUM 86 FYJC ARTS ROLL CALL DIV- A 2019 - 2020 ROLL NO NAME OF THE STUDENT ENG/ MAR / HIS/ SOC/GEO/ ECO/ EVS/ HPE 1 AMBRE NIVIYA UMESH JANHAVI 2 CHAVAN ASHWINI TANAJI ALKA 3 CHAVAN PRIYA PRAKASH PRIYANKA 4 CHOUDHARY RUFAIDA MOHD. SHAKEEL SHABANA 5 KHARADE SUMIT KISHOR SUNITA 6 KOYANDE ADITI SUHAS SAMPADA 7 KULAYE BHAVNA DILIP DARPANA 8 MORE JANHAVI SANTOSH SARIKA 9 NARSALE SANJANA DATTARAM DAKSHATA 10 PARAB JANHAVI MAHESH MANDAKINI 11 PAWAR DIKSHA MILIND SUNITA 12 RAJE RIDDHI KEDAR PRAJAKTA 13 SASANE ISHWANSHIKUMAR VINAYAK ANJALI 14 SHAIKH SHEEBA MOHAMMED AHAMMED ASMA 15 SHELAR HARSHADA KAILAS USHA 16 SHEWALE GAURI VILAS VANITA 17 SONAWANE NEHA LAWRENCE SUSHMA ENG/ SANSK / HIS/ GEO /SOC/ ECO/ EVS/ HPE 28 DALAI SUBRATH SUBHASH PUSHPA 29 KHAN HAJIRA PARVEZ ATIKA 30 SAWANT NISHAD NANDKISHOR NEHA ENG/ HIN / HIS/ GEO /SOC/ ECO/ EVS/ HPE 31 AASIYA ABRAR HUSAIN SAFIYA 32 ANSARI BUSHRABANO SHAHIDALI AMINA 33 ANSARI MARYAM MOHAMMED SALIM RAZIYA 34 ANSARI SADAF MOHAMMED KAZIM SHAHANABANU 35 ANSARI ZAINAB MAQSOOD ALI AFSANA 36 BIND MAHIMA RAJENDRAPRASAD SUNITADEVI 37 CHAUDHRY KHUSHNAZ NIYAZ ASMA 38 CHAURASIYA SANDHYA KANHAIYALAL SHANTIDEVI 39 CHAWDHARY NISHADBANOO NISAR AHMED SABIRA 40 CHOUDHARY PRITI KUMARI UPENDRA MEERA DEVI 41 CHOUDHARY RAFINA KHATOON GULAM HUSAIN SARVAR JAHAN 42 CHOUDHARY SHIFA LUTFULLAH MEHJABEEN 43 DUBEY RAMA ANIL SUMAN 44 GAUD TISHA UMESH INDU 45 GUPTA VISHAL BAJRANG SITAU 46 IDRISI SHABEENA BANO MOHAMMED WAKEEL ASFIYA BANO 47 JAISWAL MEENA TRILOKI SANGEETA 48 JAISWAR DEEPALI -

NISHAT MILLS LIMITED LIST of SHAREHOLDERS WITHOUT CNIC As on 23.11.2015 S.No. Folio No Name F/H NAME Address1 Address2 Address3

NISHAT MILLS LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WITHOUT CNIC as on 23.11.2015 S.No. Folio_no Name F/H NAME Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Shares_held 1 12 MR. ISHTIAQ AHMAD C/O QAMAR HOMEE CHAMBERS ARAM BAGH ROAD KARACHI 3 2 14 MR. AISHA BAI BAWA C/O MOHD.YOUSUF BROTHERS 29-COCHIN WALA MARKET KARACHI 152 3 15 MR. A.R.G. KHAN 27, KARACHI MEMON C. H. SOCIETY, BLOCK 7/8, HILL PARK ROAD, OFF SHAHRAHE FAISAL, KARACHI-75350. 6 4 16 MISS RASHIDA ALVI MASKAN-I-AISHA,13/H STREET-12 BLOCK NO.6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI 3 5 17 MR. AKBAR ALI BHIMJEE 34-AMIL COLONY NO.1 SADHU HIRA NAND ROAD KARACHI 24 6 18 MR. ARSHAD SALIM QURESHI 49 - 5TH STREET, PHASE V, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI 138 7 21 MR. AHMAD ULLAH AKHTAR 10 HUSSAIN SHAH STREET PARK LANE TEMPLE ROAD LAHORE 687 8 22 MST. FATIMA BAI YOUSUF 107-NAWAB ISMAIL KHAN ROAD AMIL COLONY NO-2 KARACHI 174 9 28 MR. SULTAN AHMAD C/O SHEIKH BROTHERS, 601, AL-AMEERA CENTER, SHAHRAH-E-IRAQ, SADDAR, KARACHI. 5760 10 29 MR. ABDUL VAHED ABDUL JALIL KARACHI STOCK EXCHANGE OFF MCLEOD ROAD KARACHI 3 11 32 MST. SHAHNAZ PARVEEN 786 P.I.B.COLONY KARACHI-5 182 12 35 MR. ABDUL KARIM ISMAIL 39-OUTSIDE LEA MARKET OPP:SULTAN HOTEL LEA MARKET KARACHI 24 13 36 MISS ZEBUNNISA D/O M.Y.LONGI 6-B II, 23RD STREET E , STREET CORNER, PHASE V, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 1852 14 37 MR. -

Outline 625.2 Art in Pakistan

Semester:VIII Course no:625.2 Art in Pakistan Credit Hours:2+1=3 Total Periods=60 1 Period= 45min S.No Topics Main Points References Periods 1 Indus Valley Civilization: Introduction, Geographical location , People of Moe- 1,2 jo-Daro, and Architecture Masonry: (streets, 3 Construction, Building and houses, Drainage System, wells, The Great Bath, Arts and Crafts: (Pottery, Sculpture, Seals) Gandhara Art: Introduction, Location, History, Sculpture, Rise of Buddhist Art, Architecture, Coins, Repositories of 3,4 2 Gandhara Art History Taxila: Introduction, Stupas and Monasteries at taxila, Pottery, Repositories at Sawat, Charsadda, Mardan , Peshawar, Stupas at Sindh 3 2 Harappa: Introduction, History, Geographical location, Important Features of harappan Civilization: 2 Copper objects, Seals and Sealings, Ornaments, Shell 1,2 Objects, Ceramics, Sculpture in stone 2 post Independence Period, After independence 4, 5, 6 2 Early painters: Abdur Rehman Chughtai, Ustad Allah Bux Development of painting and Art Leading Women Artist After Independence: in pakistanFrom Anna Molka Ahmed, Zubeida Agha 1947-Date Pictorial Characteristics of their work, Subject and Medium of Painting) 3 Talented Group of artists: 4, 5, 6 2 Shakir Ali, The Lahore Group, Ahmed Parvez, S Lahore in the 50’s Safdar, Shemza, Ali Imam Prominent Artists: Fayzee Rahamin, S, H.Askari, As Karachi in the 50’s Nagi, Sadequain and Gulgee Pictorial Characteristics of their work, Subject and Medium 4 Second Generation artists: Jamil Naqsh, Mansur 4, 5, 6 2 Rahi, Mansur Aye, Bashir Mirza, Hajra Mansur, Laila Karachi in the 60’s Shahzada Zahoor-ul-Akhlaque, Colin David, Saeed Akhtar, Khalid Iqbal, Ahmed khan Lahore in the 60’s Pictorial Characteristics of their work, Subject and Medium of Painting) 5 In 70’ art flourished in Karachi . -

The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009

Viewpoints Special Edition The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mei.edu Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Government of Pakistan; Flickr user Kash_if; Flickr user Kash_if; Depart- ment of Defense; European Parliament; Flickr user Al Jazeera English; Flickr user groundreporter; Flickr user groundreporter. 2 The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009 • www.mei.edu Viewpoints Special Edition The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009 The Middle East Institute Viewpoints: The Islamization of Pakistan, 1979-2009 • www.mei.edu 3 Viewpoints: 1979 The year 1979 was among the most tumultuous, and important, in the history of the modern Middle East. -

South Asian Modern Art 2019 5 –28 June 2019

South Asian Modern Art 2019 5 –28 June 2019 South Asian Modern Art 2019 Recent Acquisitions, including the Olga Bogroff Collection of works by Ram Kumar 2 3 Olga Bogroff Une galeriste à Paris dans les années 50 (A gallerist in Paris in the 50s) Olga Bogroff was born in Odessa, Russia in 1887, her family were prosperous and lived in a mansion overlooking the sea. After the Revolution in 1920 she emigrated to France with her husband Théodore and their son Serge. Having abandoned everything in Russia, they lived modestly in Paris making ends meet, him playing the cello in silent cinemas while Olga was a milliner. Théodore died in 1943. After the War the resourceful Olga transformed her apartment in the rue Hamelin into an art gallery, where every room from the kitchen to the bedroom was used as hanging space. She exhibited the works of young unknown artists, Olga Bogroff in Odessa Serge Bogroff in India such as Carmen Herrera and many others, as well as more well-known figures such as Georges Braque and Henri Goetz. The gallery was called Galerie Olga Bogroff. She was known for her warmth, hospitality and original personality. She also established the L’espalier Association. During the war Serge was a prisoner-of-war and once released he returned home to his then widowed mother, he was an art lover and encouraged his mother to paint and to open the gallery. He worked as a Consultant Engineer for the Rothschild Bank in Paris and this led him to travel frequently including several trips to India. -

THE STRUGGLE for DEMOCRACY in PAKISTAN Nonviolent Resistance to Military Rule 1977-88

THE STRUGGLE FOR DEMOCRACY IN PAKISTAN Nonviolent Resistance to Military Rule 1977-88 Malik Hammad Ahmad Police attacks a MRD rally in Karachi A dead protester in Moro The Struggle for Democracy in Pakistan Nonviolent Resistance to Military Rule 1977-88 Malik Hammad Ahmad Student No.0558694 A thesis submitted is partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. The University of Warwick Department of History May 2015 iii Dedication To my Mother - Rukhshanda Kokab For her heartiest wish receivinG higher education To my Supervisor - David Hardiman For his exceptional consistent pursuance and guidance Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENT VI DECLARATION X DISSERTATION ABSTRACT XI ILLUSTRATIONS XII ACRONYMS XIII GLOSSARY XV DISSERTATION INTRODUCTION 1 SCOPE OF THE RESEARCH: 1 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND METHODOLOGY 6 MAIN ARGUMENTS 8 LITERATURE REVIEW 22 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 29 SOURCES 34 ROADMAP 39 CH. 1. THE CAMPAIGN TO SAVE ZULFIQAR ALI BHUTTO 43 IMPOSITION OF MARTIAL LAW: 47 BHUTTO BACHAO TEHREEK: 60 UNPOPULARITY OF BHUTTO: 60 FAILURE TO CULTIVATED INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT: 67 THE CAMPAIGN: 74 ZIA’S OPPRESSION: 87 CONCLUSION 94 CH. 2. FORMATIVE PHASE OF COLLECTIVE ACTION 1979-81: 95 RE-ORGANISATION OF PPP: 95 THE REGIME’S ‘ISLAMIC’ REPRESSION: 106 TRADE UNION MILITANCY: 111 ‘REAL MARTIAL LAW’: 114 BUILDING AN ANTI-REGIME POLITICAL ALLIANCE 116 INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT: 120 CONCLUSION: 122 CH. 3. THE MOVEMENT FOR RESTORATION OF DEMOCRACY 1981-84 123 OBJECTIVE AND STRATEGIES: 123 CALL FOR CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE AUGUST 1983: 129 GOVERNMENT TACTICS TOWARDS THE MOVEMENT: 136 PROMULGATION OF PCO: 143 ROLE OF MEANS OF COMMUNICATION: 145 CIVIL SOCIETY ON BOARD: 151 SYMPATHY IN THE ARMY: 155 v AL-ZULFIQAR AND PPP’S RELATIONSHIP: 158 MRD FAILURE AND SUCCESS 1981-84 165 GRADUALIST DEMOCRACY: 165 PROBLEMS OF LEADERSHIP AND ORGANISATION: 174 EXTERNAL SUPPORT: 179 CONCLUSION 182 CH.