Ratification of International Treaties, a Comparative Law Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHTP-2009-06-National-Security-1.Pdf

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Louis Fisher is Specialist in Constitutional Law with the Law Library of the Library of Congress. The views expressed here are personal, not institutional. Earlier in his career at the Library of Congress, Fisher worked for the Congressional Research Service from 1970 to March 3, 2006. During his service with CRS he was Senior Specialist in Separation of Powers and research director of the House Iran-Contra Committee in 1987, writing major sections of the final report. Fisher received his doctorate in political science from the New School for Social Research and has taught at a number of universities and law schools. He is the author of eighteen books, including In the Name of National Security: Unchecked Presidential Power and the Reynolds Case (2006), Presidential War Power (2d ed. 2004), Military Tribunals and Presidential Power (2005), The Politics of Executive Privilege (2004), American Constitutional Law (with Katy J. Harriger, 8th ed. 2009), Constitutional Conflicts between Congress and the Presidency (5th ed. 2005), Nazi Saboteurs on Trial: A Military Tribunal and American Law (2003), and, most recently, The Constitution and 9/11: Recurring Threats to America’s Freedoms (2008). He has received four book awards. Fisher has been invited to testify before Congress on such issues as war powers, state secrets, CIA whistle-blowing, covert spending, NSA surveillance, executive privilege, executive spending discretion, presidential reorganization authority, Congress and the Constitution, the legislative veto, the item veto, the pocket veto, recess appointments, the budget process, the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act, the balanced budget amendment, biennial budgeting, presidential impoundment powers, and executive lobbying. -

Treaty of Versailles I

Treaty of Versailles I. Wilson’s Vision forWorld Peace A. Fourteen Points to End All Wars 1. Wilson’s first goal was to eliminate the causes of wars by calling for an end to secret agreements and alliances, protecting freedom of the seas, and reducing armaments. 2. Wilson’s second goal was to ensure the right to self-determination so ethnic groups and nationalities could live under governments of their own choosing. 3. The last of the fourteen points called for setting up a League of Nations to ensure world peace. B. Wilson’s Unusual Decisions 1. Wilson broke with tradition by traveling out of the United States while president to lead the U.S. delegation to the peace conference in Paris. 2. Wilson weakened his position when he asked Americans to support Democrats in the 1918 midterm elections, but then the Republicans won a majority in Congress. 3. Wilson made matters worse by choosing all Democrats and only one Republican to serve as the other delegates to the peace conference. II. Ideals Versus Self-Interest at Versailles A. Peace Without Victory Gives Way to War Guilt and Reparations 1. Wilson’s vision for a peaceful world was different from the vision of other Big Four leaders. 2. France’s Georges Clemenceau was most concerned about French security. 3. David Lloyd George wanted Germany to accept full responsibility for the war through a warguilt clause and reparations. 4. Wilson tried to restrain from punishing Germany but ultimately agreed to gain support for the League of Nations. B. Self-Determination Survives, but Only in Europe 1. -

United States Code

United States Code COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE DATING BACK TO INCEPTION IN 1925-1926, IN A FULLY SEARCHABLE, USER-FRIENDLY FORMAT! The United States Code is a consolidation and codification by subject matter of the general and permanent laws of the United States. The Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the U.S. House of Representatives prepares and publishes the United States Code pursuant to section 285b of title 2 of the Code. The Code does not include regulations issues by executive branch agencies, decisions of the Federal courts, treaties, or laws enacted by State or local governments. THE HEINONLINE ADVANTAGE HeinOnline’s version of the United States Code provides users with a single source for the entire archive along with current content of the United States Code. • Comprehensive coverage from inception • Browse by Title or Edition • Quickly find a document with the custom citation locator • Content is easy to both browse and search • Powerful search engine enables users to locate topic-specific content quickly and easily • As part of several Core packages, the U.S. Code in HeinOnline provides an incredible platform for an even better value! United States Code INCLUDES EARLY FEDERAL CODES & COMPILATIONS OF STATUTES The Early Federal Laws Collection represents the most complete collection of federal statute compilations, prior to the United States Code in 1926. The collection includes the first compilation by Richard Folwell (1795- 1814), the Bioren and Duane editions (1815), Thomas Herty Digest (1800), William Graydon’s Abridgement (1803), among others. Browse the laws by Title, Coverage, Publication Date, Volumes, Congress, or Compiler, using a custom chart of documents. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

Originalism and the Ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment

Copyright 2013 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 107, No. 4 ORIGINALISM AND THE RATIFICATION OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT Thomas B. Colby ABSTRACT—Originalists have traditionally based the normative case for originalism primarily on principles of popular sovereignty: the Constitution owes its legitimacy as higher law to the fact that it was ratified by the American people through a supermajoritarian process. As such, it must be interpreted according to the original meaning that it had at the time of ratification. To give it another meaning today is to allow judges to enforce a legal rule that was never actually embraced and enacted by the people. Whatever the merits of this argument in general, it faces particular hurdles when applied to the Fourteenth Amendment. The Fourteenth Amendment was a purely partisan measure, drafted and enacted entirely by Republicans in a rump Reconstruction Congress in which the Southern states were denied representation; it would never have made it through Congress had all of the elected Senators and Representatives been permitted to vote. And it was ratified not by the collective assent of the American people, but rather at gunpoint. The Southern states had been placed under military rule, and were forced to ratify the Amendment—which they despised—as a condition of ending military occupation and rejoining the Union. The Amendment can therefore claim no warrant to democratic legitimacy through original popular sovereignty. It was added to the Constitution despite its open failure to obtain the support of the necessary supermajority of the American people. -

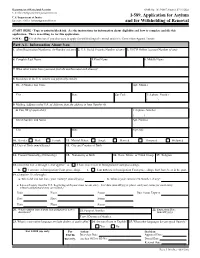

Form I-589, Application for Asylum and for Withholding of Removal

Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0067; Expires 07/31/2022 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services U.S. Department of Justice I-589, Application for Asylum Executive Office for Immigration Review and for Withholding of Removal START HERE - Type or print in black ink. See the instructions for information about eligibility and how to complete and file this application. There is no filing fee for this application. NOTE: Check this box if you also want to apply for withholding of removal under the Convention Against Torture. Part A.I. Information About You 1. Alien Registration Number(s) (A-Number) (if any) 2. U.S. Social Security Number (if any) 3. USCIS Online Account Number (if any) 4. Complete Last Name 5. First Name 6. Middle Name 7. What other names have you used (include maiden name and aliases)? 8. Residence in the U.S. (where you physically reside) Street Number and Name Apt. Number City State Zip Code Telephone Number ( ) 9. Mailing Address in the U.S. (if different than the address in Item Number 8) In Care Of (if applicable): Telephone Number ( ) Street Number and Name Apt. Number City State Zip Code 10. Gender: Male Female 11. Marital Status: Single Married Divorced Widowed 12. Date of Birth (mm/dd/yyyy) 13. City and Country of Birth 14. Present Nationality (Citizenship) 15. Nationality at Birth 16. Race, Ethnic, or Tribal Group 17. Religion 18. Check the box, a through c, that applies: a. I have never been in Immigration Court proceedings. b. I am now in Immigration Court proceedings. -

The Building As Completed, from Walter's Designs

CHAPTER XVI THE BUILDING AS COMPLETED, FROM WALTER’S DESIGNS DWARD CLARK supervised the completion of the Capitol the old Senate Chamber being devoted to the court room and the west from the designs of Thomas U. Walter, leaving the building as front being used by the court officials for office and robing rooms.1 it stands to-day. The terraces on the west, north, and south are The attic story [Plate 223] is so arranged in each wing that the a part of the general landscape scheme of Frederick Law Olm- public has access from its corridors to the galleries of the House and Ested. The building consists of the central or old building, and two wings, Senate Chambers, with provision for the press and committee rooms or the Capitol extension, with the new Dome on the old building. facing the exterior walls of the building. Document rooms are also pro- The cellar [Plate 220] contained space on the central western vided on this floor. extension available for office and committee rooms. Other portions of Plates 224, 225, 225a show the eastern front of the building as the cellar are given up to the heating and ventilating apparatus, or are completed, the principal new features being the porticoes on the wings, used for storage. Beneath the center of the Dome a vault was built in which are similar to the central portico designed by Latrobe. Although the cellar to contain the remains of George Washington, but because of the original design of Thornton contemplated a central portico he did the objection of the family to his burial in the Capitol his body never not contemplate the broad flight of steps which extends to the ground rested in the contemplated spot. -

AG RECEIVED /Lf-Osi.>:F

EC RECEIVED APR 1 6 2014 /lf- o SI.>:f EXBCtJTI'VEdm at OPTIIESECRET ARY-G.BNERAI, 14 April2014 ACTION M The Honourable Ban Ki-moon Secretary-General COPY D sf:, United Nations Headquarters c_cL c.... 2 United Nations Plaza £-s New York, New York 10017 United States of America AG The Reqm:st by Palestinian Officials to Join UN Agencies and Accede ro International Conventions Your Excellency: By way of introduction, the European Centre for Law and Justice ("ECLJ") is an international, Non-Governmental Organisation ("NGO"), dedicated, inter alia, to the promotion and protection of human rights and to the fu rtherance of the rule of law in international affairs. The ECLJ has held Special Consultative Status before the United Nations/ECOSOC since 200i. Recently, Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas submitted a series of letters to various UN agencies as well as to officials of Switzerland and the Netherlands requesting that "Palestine" be admitted to the respective UN agency or that "Palestine" be permitted to accede to the respective convention or treaty2• By submitting such requests, President Abbas is attempting to obtain recognition of Palestinian statehood "through the back door" by circumventing the provisions of solemn treaties which the PA entered into in the past. Such a manoeuvre indicates that the Palestinians are prepared to violate the terms of agreements they have entered into when such terms become inconvenient or do not lead to the results the Palestinians otherwise desire. Such actions violate fo undational principles of international law, to wit, the principle of ·'good fa ith" 3 4 and the rule of ''pacta sunt servanda" regarding treaties , and cannot be permitted or tolerated. -

Amending the U.S. Constitution by State-Led Convention

AMENDING THE U.S. CONstItutION BY StatE -LED CONVENTION INDIANA’S MODEL LEGIslatION DIstRIbutED BY: INDIANA SENatE PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE DAVID LONG AMENDING THE CONSTITUTION BY STATE‐LED CONVENTION: BACKGROUND INFORMATION U.S. CONSTITUTION, ARTICLE V: The Congress, whenever two thirds of both houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this Constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several states, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this Constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Congress; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year one thousand eight hundred and eight shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no state, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate. AMENDING THE U.S. CONSTITUTION: Article V of the U.S. Constitution provides two paths for amending the Constitution: Path 1: o Step 1: Two-thirds of both houses of Congress pass a proposed constitutional amendment. This sends the proposed amendment to the states for ratification. o Step 2: Three-fourths of the states (38 states) ratify the proposed amendment, either by their legislatures or special ratifying conventions. Path 2: o Step 1: Two-thirds of state legislatures (34 states) ask for Congress to call “a convention for proposing amendments.” o Step 2: States send delegates to this convention, where they can propose amendments to the Constitution. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

A Climate Treaty Without the US Congress: Using Executive Powers to Overcome the ‘Ratification Straitjacket’

Crawford School of Public Policy Centre for Climate Economics & Policy A climate treaty without the US Congress: Using executive powers to overcome the ‘Ratification Straitjacket’ CCEP Working Paper 1513 Nov 2015 Luke Kemp Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University Abstract The issue of US ratification of international environmental treaties is a recurring obstacle for environmental multilateralism, including the climate regime. Despite the perceived importance of the role of the US to the success of any future international climate agreement, there has been little direct coverage in terms of how an effective agreement can specifically address US legal participation. This paper explores potential ways of allowing for US legal participation in an effective climate treaty. Possible routes forward include the use of domestic legislation such as section 115 (S115) of the Clean Air Act (CAA), and the use of sole-executive agreements, instead of Senate ratification. Legal participation from the US through sole-executive agreements is possible if the international architecture is designed to allow for their use. Architectural elements such as varying legality and participation across an agreement (variable geometry) could allow for the use of sole-executive agreements. Two broader models for a 2015 agreement with legal participation through sole-executive agreements are constructed based upon these options: a modified pledge and review system and a form of variable geometry composed of number of opt-out, voting based protocols on specific issues accompanied with bilateral agreements on mitigation commitments with other major emitters through the use of S115 and sole-executive agreements under the Montreal Protocol and Chicago Convention (Critical Mass Governance). -

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court The text of the Rome Statute reproduced herein was originally circulated as document A/CONF.183/9 of 17 July 1998 and corrected by procès-verbaux of 10 November 1998, 12 July 1999, 30 November 1999, 8 May 2000, 17 January 2001 and 16 January 2002. The amendments to article 8 reproduce the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-6, while the amendments regarding articles 8 bis, 15 bis and 15 ter replicate the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-8; both depositary communications are dated 29 November 2010. The table of contents is not part of the text of the Rome Statute adopted by the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court on 17 July 1998. It has been included in this publication for ease of reference. Done at Rome on 17 July 1998, in force on 1 July 2002, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2187, No. 38544, Depositary: Secretary-General of the United Nations, http://treaties.un.org. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Published by the International Criminal Court ISBN No. 92-9227-232-2 ICC-PIOS-LT-03-002/15_Eng Copyright © International Criminal Court 2011 All rights reserved International Criminal Court | Po Box 19519 | 2500 CM | The Hague | The Netherlands | www.icc-cpi.int Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Table of Contents PREAMBLE 1 PART 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COURT 2 Article 1 The Court 2 Article 2 Relationship of the Court with the United Nations 2 Article 3 Seat of the Court 2 Article 4 Legal status and powers of the Court 2 PART 2.