Amanda Frlekin, Et Al., Apple, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

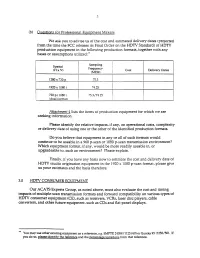

(B) Questions for Professional EQ,Uipment Makers We Ask You to Advise Us of the Cost and Estimated Delivery Dates (Projected

(b) Questions for Professional EQ,uipment Makers We ask you to advise us of the cost and estimated delivery dates (projected from the time the FCC releases its Final Qrder on the HDTV Standard) of HDTV production equipment in the following production formats, together with any bases or assumptions utilized:'· Sampling Spatial (HxV) Frequency Cost Delivery Dates (MHz) I 1280 x 720 p 75.3 1920 x 1080 i 74.25 720 p/1080 i 75.3/74.25 I (dual format) i Attachment 4 lists the items of production equipment for which we are seeking infonnation. Please identify the relative impacts, if any, on operational costs, complexity or delivery date of using one or the other of the identified production formats. Do you believe that equipment in any or all of such formats would continue to be useable in a 960 p-scan or 1080 p-scan transmission environment? Which equipment format, if any, would be more readily useable in, or upgradeable to, such an environment? Please explain. Finally, if you have any basis now to estimate the cost and delivery date of HDTV studio origination equipment in the 1920 x 1080 p-scan format, please give us your estimates and the basis therefore. 3.0 HDTV CONSUMER EQUIPMENT Our ACATS Experts Group, as noted above, must also evaluate the cost and timing impacts of multiple-scan transmission formats and forward compatibility on various types of HDTV consumer equipment (CE), such as receivers, VCRs, laser disc players, cable converters, and other future eqUipment, such as CDs and flat panel displays. -

Final 2014 Return Shares for Electronics Manufacturers Washington State Electronic Products Recycling Program 4/24/2014

Final 2014 Return Shares for Electronics Manufacturers Washington State Electronic Products Recycling Program 4/24/2014 The E-Cycle Washington program conducted 42 sampling events in 2013 gathering data on over 13,600 TVs, monitors and computers. That data was used to determine Return Share by manufacturer, summarized below. Identified Proportional Total Manufacturer Name Weight (lbs) Brands Return Orphan* Return Share (%) Share (%) Share (%) 605484 92.80937069 Sony Electronics, Inc. 66834 11.04 0.86 11.89 Panasonic Corporation of North America 54226 8.96 0.69 9.65 Philips Electronics 47779 7.89 0.61 8.50 Toshiba America Information Systems, Inc. 43922 7.25 0.56 7.82 Dell Computer Corp. 43199 7.13 0.55 7.69 Thomson, Inc. USA 43078 7.11 0.55 7.67 Hewlett Packard 26370 4.36 0.34 4.69 JVC Americas Corp. 25979 4.29 0.33 4.62 Sharp Electronics Corporation 20274 3.35 0.26 3.61 Acer America Corp. 19327 3.19 0.25 3.44 LG Electronics USA, Inc. 18656 3.08 0.24 3.32 Mitsubishi Electric Visual Solutions America, Inc. 17906 2.96 0.23 3.19 Osram Sylvania 15226 2.51 0.19 2.71 Samsung Electronics Co. 14872 2.46 0.19 2.65 Apple 14537 2.40 0.19 2.59 Hitachi America, LTD. Digital Media Division 11235 1.86 0.14 2.00 ViewSonic Corp. World HQ 9934 1.64 0.13 1.77 Emerson Radio Corp. 7163 1.18 0.09 1.27 General Electric Co. 5691 0.94 0.07 1.01 NEC Display Solutions 4833 0.80 0.06 0.86 TMAX Digital, Inc. -

August 19, 1991 Issue (Dig081991.Pdf)

Issue 91-160 August 19, 1991 I, J~.'.' 0 lUlJlI , u.s. SECURITIES IiUQ' I"'CE CAUPMSS'ON ADMINISTRATlVE>PROCEEDINGS PROCEEDINGS AGAINST ANDREW DOHERTY, RONALD DIPRATO AND MICHAEL JACOBS On August 12, the Commission issued an order instituting cease and desist proceedings pursuant to Section 21C(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 against Andrew Doherty and Ronald N. DiPrato, formerly a registered representative with Advest, Inc. The Commission also instituted public administrative proceedings pursuant to Section l5(b)(6) of the Exchange Act against DiPrato and Michael H. Jacobs, a registered representative with Advest and formerly manager of Advest's Hartford branch office, and made findings related thereto. In the Order, the Commission found that Doherty and DiPrato violated Sections lO(b) and l3(d) of the Exchange Act and Rules lOb-S, l3d-l and 13d-2 thereunder. The Commission also found that DiPrato aided and abetted Doherty'S violations of Section lO(b) and Rule lOb-S thereunder by manipulating the price of the stock of TeleConcepts Corp. through the practice of "marking the close". In addition, the Commission found that Jacobs, DiPrato's direct supervisor, failed to supervise DiPrato. The Commission ordered Doherty and DiPrato permanently to cease and desist from any future violations of Sections lO(b) and l3(d) of the Exchange Act and Rules 10b-S, l3d-l and l3d-2 thereunder, and ordered DiPrato permanently to cease and desist from aiding and abetting violations of Section lO(b) and Rule lOb-S. The Commission also suspended DiPrato for four months and Jacobs for one month from association with any broker, dealer, investment adviser, investment company or municipal securities dealer. -

Warranty on a Manufacturer's Product Will Apply When Purchased

Warranties and Manufacturer Contact Information Any warranty on a manufacturer's product will apply when purchased. To receive a free copy of the manufacturer's warranty, either before you buy or as a replacement, write to: Attn: Warranty Request Customer Care, P.O. Box 949 Minneapolis, MN 55440 Or call (1-888-237-8289). You can also contact the manufacturer directly. Manufacturers' Contact Information Manufacturer Phone Number 0-9 Back to top 01 Communique Laboratory, Inc. 905-795-2888 3DO Company 650-261-3454 3M 888-364-3577 989 Studios 800-345-7669 A Back to top Absocold 888-396-7501 Absolute Software 800-220-0733 Acclaim 516-759-7800 Acer 866-695-2237 Actiontec 800-371-0442 Actiontec 408-752-7700 Activision 310-255-2050 Adaptec 800-442-7274 Admiral (Maytag) 800-688-9900 Adobe Systems 800-833-6687 ADS Technologies 562-926-4338 Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) 800-222-9323 Advent (NHT) 800-732-6866 Advent TV 888-474-2314 Aerial Communications (Voicestream) 800-937-8997 Agetech 408-736-8001 AG Neovo 866-246-3686 Aiptek 949-585-9600 AI Tech International 800-882-8184 Airtouch Cellular & Paging (Verizon) 800-626-6611 Aiwa 800-289-2492 Alaron 800-521-3832 Alienware 866-287-6727 Alienware 800-494-3382 Allsop 800-426-4303 Alpine 800-257-4631 Altec Lansing 800-258-3288 Amana 800-843-0304 AMD (Advanced Micro Devices) 877-284-1566 America Online 800-827-6364 American Action 909-869-6600 American International 800-336-6500 American Power Conversion 800-800-4272 American Terminal Supply 800-826-4697 Antec 888-542-6832 AOC (EPI) 800-343-5777 AOL 800-827-6364 APC 800-555-2725 Apex Digital, Inc. -

Senate Side of the Capitol and in the Tee on Rules and Administration to My Tion 3066, in the Rank Indicated: Senate Office Buildings

9362 - CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE May 28 functions in the public rooms ·on · the I shall await the reply of the Commit the President ·under subsection (a) of sec Senate side of the Capitol and in the tee on Rules and Administration to my tion 3066, in the rank indicated: Senate Office Buildings. I have made letter. If, as a Member of this body who To be lieutenant generals clear that there are some of us who be has demonstrated time and time again Maj. Geil. Theodore William Parker, lieve that this is a horrendous example in his many years of service his complete 018369, Army of the United States (briga to be setting for the youth of this coun parliamentary fairness to all other dier general, U.S. Army). try. Each day literally thousands of Members of the Senate, I cannot obtain 1. The following-named officer to be placed high school and college students, who a hearing on my resolution, if I cannot on the retired list, in the grade indicated, bring before the Committee on Rules and under the provisions of title 10, United represent the greatest wealth we have, States Code, section 3962: come through the corridors of the Capi Administration the witnesses who wish Lt. Gen. John Honeycutt Hinrichs, tol and the corridors of the Senate Office to testify on the resolution, I shall use 017174, Army of the United States (major Buildings. I do not believe it is a very every parliamentary right at my com general, U.S. Army). good thing to have them visiting the mand from now until Congress adjourns, 2. -

Brand Association List Is Your Registration up to Date?

Last updated: 7/30/19 Brand Association List Below is the list of brands used in the 2020 Tier Assignment Schedule for Washington’s Electronic Product Recycling Program. Brands are associated with the responsible manufacturer. The manufacturers listed are those Ecology has identified as the brand owners of electronic products covered by this program (computers, monitors, laptops, televisions, portable DVD players, tablets, and e-Readers). Is Your Registration Up to Date? • Manufacturers who own additional brands of covered electronic products not currently registered must add those brands to their registration. • Brand owners of covered electronic products that are not on this list must register as a new participant. • Access your registration by going to our webpage for manufacturers and clicking “Submit my annual registration.” If you have questions, please contact Jade Monroe at 360-407-7157 or [email protected]. Brand Manufacturer 2go PC Computer Technology Link 3D Corporation 3D Corporation 3M Dynapro 3M Touch Systems 4th Dimension Computer 4th Dimension Computer 888 (Chinese Characters) Fry's Electronics, Inc. Abacus Abacus Office Machines ABS ABS Computer Technologies Inc ABS Newegg ACC Tech ACC Tech ACC Tech Angel Computer Systems Inc Access HD GXi International Accu Scan J.C. Penney Corporation, Inc. Accurian General Wireless Operations Inc dba RadioShack Accuvision QubicaAMF Acer Acer America Corp ACI Micro ACI Micro ACW Computer Warehouse of Central Florida, Inc ADEK ADEK Industrial Computers Ademco Honeywell ACS Division ADP ADP ADT ADT LLC dba ADT Security Services ADVENT VOXX International Corp. Affinity Kith Consumer Product Inc. AFUNTA Afunta LLC Last updated: 7/30/19 AG Neovo AG Neovo Technology Corp Agasio Amcrest Technologies LLC AGPTEK Mambate USA, Inc. -

Scott Howard, Et Al. V. Emerson Radio Corporation, Et Al. Howard-Class

LIONEL Z. GLANCY MICHAEL GOLDBERG GLANCY & BINKOW LLP 1801 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 311 Los Angeles, California 90067 Telephone: (310) 201-9150 Facsimile: (310) 201-9160 Attorneys for Plaintiff Scott Howard UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY SCOTT HOWARD, Individually And On No. Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, Plaintiffs, CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT v. FOR VIOLATIONS OF FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS GEOFFREY P. JURICK, KENNETH A. CORBY, JOHN J. RABB and EMERSON JURY TRIAL DEMANDED RADIO CORP., Defendants. Plaintiff, by his attorneys, for his Class Action Complaint, alleges the following upon personal knowledge as to himself and its own acts, and upon information and belief based upon the investigation of plaintiff’s attorneys as to all other matters. The investigation includes the thorough review and analysis of public statements, publicly filed documents of Emerson Radio Corp. (“Emerson” or the "Company”), press releases, news articles and the review and analysis of accounting rules and related literature. Plaintiff believes that further substantial evidentiary support will exist for the allegations set forth below after a reasonable opportunity for discovery. SUMMARY OF ACTION 1. This is a securities class action on behalf of public investors who purchased the securities of Emerson during the period from January 29, 2003 through August 12, 2003 (the "Class Period"). Plaintiff complains of a fraudulent scheme and deceptive course of business that injured purchasers of Emerson stock during the Class Period. 2. Emerson, a Delaware corporation, headquartered in New Jersey, is a consumer electronics distributor that designs, sources, imports and markets television and other video products, microwave ovens, audio, home theater, specialty and other consumer electronic products. -

Quick Start Guide MP320 (256MB)

Location of Controls VOLUME + BUTTON HOLD SWITCH LCD DISPLAY HEADPHONE JACK VOLUME - BUTTON USB CAP U EN M FWD BUTTON POWER/PLAY/ PAUSE/STOP BUTTON MP120 (128MB) MENU BUTTON BATTERY COMPARTMENT REV BUTTON Quick Start Guide MP320 (256MB) Copyright/Trademarks Warning Troubleshooting © 2005 Emerson Radio Corp. All rights reserved. To reduce the risk of shock hazard, do not expose this product to rain or any type of moisture, Player is not recognized on my Windows® 98 computer: Download and install as well as do not disassemble the player. There are no user-serviceable parts inside. the MP120/MP320 driver from www.emersonradio.com. Connect the player to Emerson Radio Corp. shall not be liable for any errors contained herein or for your computer and follow your operating system's instructions to finish installing any damages arising out of or related to this document or the information Caution: Any changes or modifications not expressly approved by the party responsible for compliance could void the user's authority to operate this device. the driver. contained herein, even if Emerson Radio Corp. has been advised of the possibility of such damages. This document is intended for informational and Shield cables must be used with this unit to ensure compliance with the Class B FCC If player is still not recognized, locate the Universal Serial Bus (USB) devices instructional purposes only. Emerson Radio Corp. reserves the right to make limits. in your operating system's device manager. If your MP120/MP320 driver displays a problem, follow your operating instruction's directions for updating changes in the specifications and other information contained in this Risk of explosion, damage or battery leakage is possible if battery is replaced or inserted the device driver and load the downloaded MP120/MP320 driver. -

![Emerson Alarm Clock User Manual [CKS1507 W/ Radio]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3995/emerson-alarm-clock-user-manual-cks1507-w-radio-2713995.webp)

Emerson Alarm Clock User Manual [CKS1507 W/ Radio]

AVERTISSEMENT 1. ALARM 1 Radio/Buzzer Indicators 14. VOLUME- DOWN Button Ne pas ingerer la pile, Danger de brOlure chimique 3 Preparation For Use 15. (La telecommande fournie avec) Ce produit contient une pile bouton. Si la pile bouton 2. AM Indicator ( 'On'=AM , 'Off'=PM) SET/TUNE UP Button 3. AUX Indicator 16. SOURCE (FM,Bluetooth,AUX) Button est avalee, elle peut provoquer de graves brOlures intern es en 2 heures seulement et Unpacking And Set Up peut entrainer la mart. 4. DAY of WEEK Indicators 17. VOLUME+ UP Button • Remove the radio from the carton and remove all packing material from the radio.Save Conserver les piles neuves et usees hors deportee des enfants. 5. LOW BATTERY Indicator 18. AC Adapter Si le compartiment pile ne se ferme pas correctement, cesser d'utiliser le produit et the packing material.if possible,in case the radio ever needs to be serviced or transpo 6. MHZ (FM Radio) Indicator 19 FM Antenna(cable) tenir hors deportee des enfants.En cas de doute concernant le fait que les piles rted.The original carton and packing material is the only safe way to pack your radio to 7. BT (Bluetooth) Indicator 20. BACKUP BATTERY Compartment pourraient avoir ete avalees ou introduites dans une partie quelconque du corps, protect it from damage in transit. 8. ALARM 2 Radio/Buzzer Indicators (located on back of unit) consulter immediatement un medecin. • Remove any descriptive labels or stickers on the front or top of the cabinet. 9. POWER ( 'On'/Standby) Button 21. Night Light On/Off Button 10 When a plug on the unit is used as a disconnect device.this unit must remain readily accessible. -

Emerson Radio Corporation Securities Litigation 03-CV-4201-Amended Consolidated Complaint

Case 2:03-cv-04201-JLL-RJH Document 21-1 Filed 03/29/2004 Page 1 of 52 LITE DEPALMA GREENBERG & RIVAS, LLC Joseph J. DePalma (JD-7697) Susan D. Pontoriero (SP-0463) Two Gateway Center, 12th Floor Newark, New Jersey 07102 Plaintiffs’ Co-Liaison Counsel (Additional Counsel on Signature Page) UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Civil Action No. 03-cv-4201 IN RE EMERSON RADIO CORP. (JLL) SECURITIES LITIGATION AMENDED CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT Lead Plaintiffs, Clark E. Niss and Jeffrey Hoffman (“Plaintiffs”), by and through their attorneys, allege the following based upon, inter alia, the investigation of their attorneys, including without limitation: (a) review and analysis of public filings made by Emerson Radio Corporation (“Emerson” or the “Company”) with the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"); (b) review and analysis of securities analysts' reports concerning Emerson; (c) review and analysis of press releases, transcripts of investor conference calls and other publications disseminated by or on behalf of Emerson; (d) review and analysis of news articles concerning Emerson; (e) interviews with former employees of Emerson; and (f) review and analysis of other publicly available information about Emerson. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1. Plaintiffs bring this class action alleging violations of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78, et seq., (the "Exchange Act") against Emerson as well as current executives, Geoffrey P. Jurick (“Jurick”), Kenneth A. Corby (“Corby”), John. J. Raab (“Raab”), and director Jerome H. Farnum (“Farnum”) (collectively the “Individual Case 2:03-cv-04201-JLL-RJH Document 21-1 Filed 03/29/2004 Page 2 of 52 Defendants”) on behalf of a proposed class and subclass of persons who purchased or acquired Emerson common stock on the open market or otherwise from January 29, 2003 through August 12, 2003, inclusive (the “Class Period”) and who suffered economic damages, as defined below. -

Download the Linecard

REMOVE DELL SERVER 1019 IT Resellers: 800-340-1001 Campus Bookstores: 800-340-1003 World-class Service CE, Home & Outdoor, Sports & Rec: 800-340-1007 Education Resellers: 800-699-7511 Comprehensive Selection Video Gaming: 800-340-1002 K12 Institution Sales: 800-340-1006 www.dandh.com @dandh D&H Distributing @DandHDistributing D&H Distributing D&H Distributing proudly supports members of these organizations Manufacturers in blue have been added recently Bags & Carry Belkin Dell Consumer HP Consumer Logitech Mophie LLC Targus Cases Canon Camcorders DigiPower HP Hardware Mac Locks Otter Products Trust Gaming Canon Cameras Ematic HP-CTO MacAlly Pelican Products Wacom Tech Corp. 3Dconnexion Case Logic Fellowes Incipio Technologies Manhattan Razer USA Zagg - iFrogz 3M Company CRU-DataPort Griffin Technology Kensington Max Cases Samsung IT Acer America Corp. Cyber Acoustics Higher Ground Gear Lenovo Microsoft Surface Speck Products Acer Consumer Dell Commercial HP Business Lenovo Idea Mobile Edge STM Bags Computer & C2G Dell Consumer Incipio Technologies Mac Locks Startech.com Verbatim AV Cables Cisco Meraki DigiPower Intellinet MacAlly Supermicro Viewsonic Cisco Refresh Ematic IOGear Manhattan Targus Visiontek Acer America Corp. Thermaltake Cisco Systems Fellowes Kanex Microsoft Surface Wacom Tech Corp. APC by Schneider TRENDnet Electric Coolermaster Gefen Kensington NETGEAR Wilson Electronics Tripp Lite CRU-DataPort Griffin Technology Lenovo PNY Technologies Aten Corp Tripp Lite Mfg Co. Wiremold/Legrand AVer Information Cyberpower HP Business Lenovo Idea Scosche Ubiquiti Networks Xavier Professional Belkin Dell Commercial HP-CTO Linksys Siig Commercial Cable Computer AVer Information Dell Commercial Hauppauge Computer Landing Zone MSI Systems TP-Link Accessories Badgy Dell Consumer Works Lenovo MSI Video TRENDnet Battery Biz Dell Military HP Business Lenovo Idea myCharge 3Dconnexion Tripp Lite Belkin DigiPower HP Commercial Linksys Patriot Memory Acer America Corp. -

Registered Electronics Manufactures

MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Land Management Administration • Resource Management Program 1800 Washington Boulevard • Suite 610 • Baltimore, Maryland 21230-1719 410-537-3314 • 800-633-6101 x3314 • www.mde.maryland.gov Registered Electronics Manufactures per Maryland's Statewide Electronics Recycling Program Law eManufacturers Registered to Sell Products in Maryland from March 1, 2017 to February 28, 2018 (Manufacturer links are provided for companies with Department-approved takeback programs and that will recycle their electronic device brands for free. Additional manufacturer links are provided in the "Electronics Take Back and Recycling Programs" section on the eCycling homepage.) • 3M Touch Systems, Inc. (010406-22; 3M Dynapro, 3M Microtouch, 3M Touch Systems, Dynapro) • Aberdeen LLC (021113-130) • Acer America Corporation (122005-04; Acer, Gateway) • Aluratek, Inc. (090414-182; Aluratek) • Amazon Fulfillment Services, Inc. (092413-154; Kindle Fire, Fire) • American Reliance, Inc. (011911-107; Amrel, Rocky) • American Network Solutions (080616-243; Sprint State, American Network Solutions, ANS) • Apple, Inc. (122805-16; Apple, Next) • Arcadian Computers LLC (121615; Arcadian, Gigabyte, ASUS, Samsung, Intel, Corsair) • ASUS Computer International (010610-97; ASUS, Nexus ASUS) • Atyme Corporation, Inc. (040317-248; Atyme) • Baby's Journey, Inc. (063015-216; Babies R US, AT&T) • Bang & Olufsen America, Inc. ( 050208-87; Bang & Olufsen) • Barco, Inc. (091113-153; Barco) • Best Buy (053105-36; Insignia, Dynex, Toshiba, Sharp, Digiland) • Blackberry Ltd. (12111-125; BlackBerry Z30, BlackBerry Leap, BlackBerry Passport, Blackberry PRIV smartphone, DTEK50 Smartphone, DTEK60 smartphone) • BLU Products, Inc. (092214-191; BLU) • Boxx Technologies, Inc.(042015-205; Boxx, Go Boxx, Render Boxx, Apexx) • BULL ITT Group LLC. (080317-250; CAT) • Canon U.S.A, Inc.