Judging Electoral Districts in America, Canada, and Australia Erin Daly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRESIDENT of the UNITED STATES (Vote for 1) COUNTY of KINGS GENERAL ELECTION

Page: 1 of 11 11/30/2020 3:53:11 PM COUNTY OF KINGS GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 3, 2020 FINAL OFFICIAL RESULTS Elector Group Counting Group Voters Cast Registered Voters Turnout Total Election Day 3,876 6.44% Vote by Mail 39,221 65.18% Provisional 1,345 2.24% Total 44,442 60,173 73.86% Precincts Reported: 96 of 96 (100.00%) Voters Cast: 44,442 of 60,173 (73.86%) PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES (Vote for 1) Precincts Reported: 96 of 96 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 44,442 / 60,173 73.86% Candidate Party Total JOSEPH R. BIDEN AND DEM 18,699 42.63% KAMALA D. HARRIS DONALD J. TRUMP AND REP 24,072 54.88% MICHAEL R. PENCE GLORIA LA RIVA AND SUNIL PF 178 0.41% FREEMAN ROQUE "ROCKY" DE LA FUENTE GUERRA AND AI 180 0.41% KANYE OMARI WEST HOWIE HAWKINS AND GRN 125 0.28% ANGELA NICOLE WALKER JO JORGENSEN AND JEREMY LIB 604 1.38% "SPIKE" COHEN Total Votes 43,861 Total BRIAN CARROLL AND AMAR WRITE-IN 0 0.00% PATEL MARK CHARLES AND WRITE-IN 1 0.00% ADRIAN WALLACE JOSEPH KISHORE AND WRITE-IN 0 0.00% NORISSA SANTA CRUZ BROCK PIERCE AND KARLA WRITE-IN 1 0.00% BALLARD JESSE VENTURA AND WRITE-IN 1 0.00% CYNTHIA MCKINNEY Page: 2 of 11 11/30/2020 3:53:11 PM UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 21st District (Vote for 1) Precincts Reported: 96 of 96 (100.00%) Total Times Cast 44,442 / 60,173 73.86% Candidate Party Total TJ COX DEM 16,611 38.10% DAVID G. -

Approach to Constitutional Principles and Environmental Discretion in Canada

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2019 Approach to Constitutional Principles and Environmental Discretion in Canada Lynda Collins University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law Lorne Sossin Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: 52:1 U.B.C. L. Rev. 293 (2019) Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Administrative Law Commons, and the Environmental Law Commons Repository Citation Collins, Lynda and Sossin, Lorne, "Approach to Constitutional Principles and Environmental Discretion in Canada" (2019). Articles & Book Chapters. 2740. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/2740 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. IN SEARCH OF AN ECOLOGICAL APPROACH TO CONSTITUTIONAL PRINCIPLES AND ENVIRONMENTAL DISCRETION IN CANADA LYNDA COLLINS, & LORNE SOSSINt I. INTRODUCTION One of the most important and least scrutinized areas of environmental policy is the exercise of administrative discretion. Those committed to environmental action tend to focus on law reform, international treaties, and political commitments-for example, election proposals for carbon taxes and pipelines, or environmental protections in global protocols and trade agreements. Many proponents of stronger environmental protection have focused their attention on the goal of a constitutional amendment recognizing an explicit right to a healthy environment,' while others seek recognition of environmental protection within existing Charter rights.2 As the rights conversation evolves,, advocates t Professor with the Centre for Environmental Law and Global Sustainability at the University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law, situated on the traditional territory of the Algonquin Nation. -

Natural Resources,Mobility Rights,Meech Lake Accord

Habeas Corpus Existing since the 13th century, habeas corpus is both a free- standing right and, more recently, a right protected under section 10(c) of the Charter.[1] Habeas Corpus translates to “produce the body”.[2] A habeas corpus application is used by persons who feel they are being wrongfully detained. Upon application, the individual is brought before a judge who will determine whether the detainment is lawful. Provincial courts must hear these applications quickly. The right is available to all individuals in Canada, including refugees and immigrants.[3] Habeas corpus is most often used when a person is being detained against their will and is suffering a deprivation of liberty. Most applications are brought by prisoners detained in correctional institutions and by immigration, child welfare, and mental health detainees.[4] An example of an unlawful detainment is a prisoner being moved from a minimum-security prison to a maximum-security prison without being told why he or she is being moved. If habeas corpus is granted, the individual’s detainment will change such that it is no longer considered illegal. This could include moving a prisoner from a maximum- security back to a minimum-security prison or even releasing the prisoner all together. The Supreme Court of Canada has described habeas corpus as a “vehicle for reviewing the justification for a person’s imprisonment”.[5] A habeas corpus application will typically be approved in cases where an individual has proved two things: 1. Their liberty was deprived in some way.[6] Three circumstances typically lead to a deprivation of liberty: 1. -

Exponent Salary Guide Hourly Waged Student Makes Over $6K in Union

Exponent Hourly Employees Salary Guide Section A Purdue advisers Hourly waged student makes are getting paid differently depending over $6k in Union last year on school. BY TAYLOR VINCENT & tion of what he does and he usually does when he needs to in order to work under MORGAN HERROLD not work more than what students typi- pressure. PAGE 5 Assistant Features Editor and Features Editor cally would in most jobs, despite making “While sometimes it may seem that such a substantially higher income last (Taylor) purposely leaves himself a short- One Purdue student earned the most year than other students. er amount of time to complete the every- money of any Purdue student employee “My job really doesn’t take up much day task, I think that is just his way of Take a look at where last year, while maintaining an hourly time out of my schedule,” Brewer said. challenging himself, but sometimes to my wage of $5.05 an hour. “I plan my classes so that I can work dismay,” Jones said. “Ultimately, it is the athletic director Taylor Brewer, a senior in the College of Tuesday and Thursday lunch shifts, so it working under pressure that is key to be- Technology, made $6,328.02 last year as doesn’t interfere with other things I do. I ing a successful server. Each day presents Morgan Burke a server in the Purdue Memorial Union. usually work around 10 hours a week and different challenges and you never when While being paid on the lowest hourly rate more if I’m scheduled on a weekend shift.” that unexpected rush is going to catch off stands amongst his for student employees, tips were a big part Ryan Jones, the Sagamore Restaurant guard.” of his total income for the year. -

021215Front FREE PRESS FRONT.Qxd

How to Voices of the Does Race Ancestors: Handle Quotes from Play a Role Great African a Mean Americans Leaders Child in Tipping? that are Still Page 2 Relevant Today Page 7 Page 4 Win $100 PRST STD 50c U.S. Postage PAID Jacksonville, FL in Our Permit No. 662 “Firsts” RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED History Contest Page 13 50 Cents Dartmouth College Introduces Volume 28 No. 14 Jacksonville, Florida February 12-17, 2015 #BlackLivesMatter Course Police Killings Underscore #BlackLivesMatter is what many bill as the name of the current move- ment toward equal rights. The hashtag, which drove information about protests happening in cities around the world, was started by Opal the Need for Reform Tometi, Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza in 2012, in response to the By Freddie Allen fatally shooting Brown. killing of Trayvon Martin. NNPA Correspondent Targeting low-level lawbreakers Now the movement has found its way into academic spaces. Blacks and Latinos are incarcer- epitomizes “broken windows” pop- Dartmouth College is introducing the #BlackLivesMatter course on its ated at disproportionately higher ularized during William Bratton’s campus this spring semester that will take a look at present-day race, rates in part because police target first tenure as commissioner of the structural inequality and violence issues, and examine the topics in a them for minor crimes, according a New York Police Department under historical context. report titled, “Black Lives Matter: then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Mayor “10 Weeks, 10 Professors: #BlackLivesMatter” will feature lectures Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Bill de Blasio reappointed Bratton from about 15 professors at Dartmouth College across disciplines, Criminal Justice System” by the to that position and he remains including anthropology, history, women's and gender studies, English Sentencing Project, a national, non- “committed to this style of order- and others. -

Write-Ins Race/Name Totals - General Election 11/03/20 11/10/2020

Write-Ins Race/Name Totals - General Election 11/03/20 11/10/2020 President/Vice President Phillip M Chesion / Cobie J Chesion 1 1 U/S. Gubbard 1 Adebude Eastman 1 Al Gore 1 Alexandria Cortez 2 Allan Roger Mulally former CEO Ford 1 Allen Bouska 1 Andrew Cuomo 2 Andrew Cuomo / Andrew Cuomo 1 Andrew Cuomo, NY / Dr. Anthony Fauci, Washington D.C. 1 Andrew Yang 14 Andrew Yang Morgan Freeman 1 Andrew Yang / Joe Biden 1 Andrew Yang/Amy Klobuchar 1 Andrew Yang/Jeremy Cohen 1 Anthony Fauci 3 Anyone/Else 1 AOC/Princess Nokia 1 Ashlie Kashl Adam Mathey 1 Barack Obama/Michelle Obama 1 Ben Carson Mitt Romney 1 Ben Carson Sr. 1 Ben Sass 1 Ben Sasse 6 Ben Sasse senator-Nebraska Laurel Cruse 1 Ben Sasse/Blank 1 Ben Shapiro 1 Bernard Sanders 1 Bernie Sanders 22 Bernie Sanders / Alexandria Ocasio Cortez 1 Bernie Sanders / Elizabeth Warren 2 Bernie Sanders / Kamala Harris 1 Bernie Sanders Joe Biden 1 Bernie Sanders Kamala D. Harris 1 Bernie Sanders/ Kamala Harris 1 Bernie Sanders/Andrew Yang 1 Bernie Sanders/Kamala D. Harris 2 Bernie Sanders/Kamala Harris 2 Blain Botsford Nick Honken 1 Blank 7 Blank/Blank 1 Bobby Estelle Bones 1 Bran Carroll 1 Brandon A Laetare 1 Brian Carroll Amar Patel 1 Page 1 of 142 President/Vice President Brian Bockenstedt 1 Brian Carol/Amar Patel 1 Brian Carrol Amar Patel 1 Brian Carroll 2 Brian carroll Ammor Patel 1 Brian Carroll Amor Patel 2 Brian Carroll / Amar Patel 3 Brian Carroll/Ama Patel 1 Brian Carroll/Amar Patel 25 Brian Carroll/Joshua Perkins 1 Brian T Carroll 1 Brian T. -

Official Results November 4, 2008 General Election

Fairfield County Board of Elections 951 Liberty Drive (740) 687-7000 / (614) 837-0765 Lancaster, OH 43130-8045 fax (740) 681-4727 www.fairfieldelections.com [email protected] OFFICIAL RESULTS NOVEMBER 4, 2008 GENERAL ELECTION Fairfield County Board of Elections 951 Liberty Drive (740) 687-7000 / (614) 837-0765 Lancaster, OH 43130-8045 fax (740) 681-4727 www.fairfieldelections.com [email protected] RESULTS OF OVERLAPPING RACES (FAIRFIELD COUNTY MOST POPULOUS) 13 – CITY OF PICKERINGTON – NATURAL GAS AGGREGATION FAIRFIELD AND FRANKLIN COUNTY FAIRFIELD FRANKLIN TOTAL FOR 4452 10 4462 AGAINST 3040 16 3056 TOTAL 7492 26 7518 14 – CITY OF PICKERINGTON – INCOME TAX INCREASE FAIRFIELD AND FRANKLIN COUNTY FAIRFIELD FRANKLIN TOTAL FOR 2936 3 2939 AGAINST 5360 25 5385 TOTAL 8296 28 8324 Fairfield County Board of Elections 951 Liberty Drive (740) 687-7000 / (614) 837-0765 Lancaster, OH 43130-8045 fax (740) 681-4727 www.fairfieldelections.com [email protected] RESULTS OF ALL RACES FAIRFIELD COUNTY ONLY NOT INCLUDING ANY OVERLAP RESULTS Election Summary Report Date:12/09/08 Time:15:21:05 FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO Page:1 of 5 GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 4, 2008 Summary For Jurisdiction Wide, Multiple Counters, All Races OFFICIAL RESULTS Registered Voters 106582 PRESIDENTIAL COMMISSIONER 1/3/09 Total Total Times Counted 72665/106582 68.2 % Times Counted 72665/106582 68.2 % Total Votes 72148 Total Votes 64300 Times Over Voted 32 Times Over Voted 1 CHUCK BALDWIN 160 0.22% HALLARN, GEORGE 26322 40.94% BOB BARR 267 0.37% MYERS, JON -

12; Duranti F., Corti E Parlamenti

Between Judicial Activism and Political Cooperation: The Case of the Canadian Supreme Court* Andrea Buratti 1. On the occasion of the 150th anniversary, of the British North America Act (1867), a group of Italian comparative law scholars dedicated two publications to Canadian constitutional law. They are G. Martinico, G. Delledonne, L. Pierdominici, Il costituzionalismo canadese a 150 dalla Confederazione. Riflessioni comparatistiche, Pisa University Press, 2017; and the special issue of “Perspective on federalism”, vol 9(3), 2017, The Constitution of Canada: History, Evolution, Influence, and Reform. These two works – which also involve distinguished foreign scholars – cover a wide range of topics: the legal systems, federalism and the Québec case, fundamental rights, the Supreme Court, etc. Despite the variety of authors and the heterogeneity of their backgrounds, all the chapters are well linked one with the other, and homogeneous in style and methodology. In this post, I will focus only on the chapters dealing with constitutional adjudication. On this issue, Canadian constitutionalism plays a relevant role, because it is placed in a middle ground between English and American traditions. Moreover, Canadian law brought on peculiar innovations in the landscape of comparative law, and represents, as I will try to underline, a model for alternative approaches to constitutional adjudication. 2. Canadian constitutionalism has always been a crucial case for comparative law, because of the peculiarities of its multicultural society, its heterogeneity, and its interconnections of the legal systems, which shows the asymmetric structure of its federalism. In this perspective, Canadian constitutional law is a lab in which many solutions of legal syncretism and institutional innovation are experienced. -

PRESIDENT of the UNITED STATES (Vote for 1) COUNTY of KINGS GENERAL ELECTION

Page: 1 of 11 10/25/2020 12:53:40 PM COUNTY OF KINGS GENERAL ELECTION - NOVEMBER 3, 2020 UNOFFICIAL RESULTS #1 Elector Group Counting Group Voters Cast Registered Voters Turnout Total Election Day 0 0.00% Vote by Mail 0 0.00% Provisional 0 0.00% Total 0 60,173 0.00% Precincts Reported: 0 of 96 (0.00%) Voters Cast: 0 of 60,173 (0.00%) PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES (Vote for 1) Precincts Reported: 0 of 96 (0.00%) Total Times Cast 0 / 60,173 0.00% Undervotes 0 Candidate Party Total JOSEPH R. BIDEN AND DEM 0 N/A KAMALA D. HARRIS DONALD J. TRUMP AND REP 0 N/A MICHAEL R. PENCE GLORIA LA RIVA AND SUNIL PF 0 N/A FREEMAN ROQUE "ROCKY" DE LA FUENTE GUERRA AND AI 0 N/A KANYE OMARI WEST HOWIE HAWKINS AND GRN 0 N/A ANGELA NICOLE WALKER JO JORGENSEN AND JEREMY LIB 0 N/A "SPIKE" COHEN Total Votes 0 Total BRIAN CARROLL AND AMAR WRITE-IN 0 N/A PATEL MARK CHARLES AND WRITE-IN 0 N/A ADRIAN WALLACE JOSEPH KISHORE AND WRITE-IN 0 N/A NORISSA SANTA CRUZ BROCK PIERCE AND KARLA WRITE-IN 0 N/A BALLARD JESSE VENTURA AND WRITE-IN 0 N/A CYNTHIA MCKINNEY Page: 2 of 11 10/25/2020 12:53:40 PM UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 21st District (Vote for 1) Precincts Reported: 0 of 96 (0.00%) Total Times Cast 0 / 60,173 0.00% Undervotes 0 Candidate Party Total TJ COX DEM 0 N/A DAVID G. -

Download Download

THE SUPREME COURT’S STRANGE BREW: HISTORY, FEDERALISM AND ANTI-ORIGINALISM IN COMEAU Kerri A. Froc and Michael Marin* Introduction Canadian beer enthusiasts and originalists make unlikely fellow travellers. However, both groups eagerly awaited and were disappointed by the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in R v Comeau.1 The case came to court after Gerard Comeau was stopped and charged by the RCMP in a “sting” operation aimed at New Brunswickers bringing cheaper alcohol from Quebec across the provincial border to be enjoyed at home.2 Eschewing Gerard Comeau’s plea to “Free the Beer”, the Court upheld as constitutional provisions in New Brunswick’s Liquor Control Act, which made it an offence to possess liquor in excess of the permitted amount not purchased from the New Brunswick Liquor Corporation.3 The Court’s ruling was based on section 121 of the Constitution Act, 1867, which states that “[a]ll articles of Growth, Produce, or Manufacture of any one of the Provinces…be admitted free into each of the other Provinces.”4 In the Court’s view, this meant only that provinces could not impose tariffs on goods from another province. It did not apply to non-tariff barriers, like New Brunswick’s monopoly on liquor sales in favour of its Crown corporation. In so deciding, the Court upheld the interpretation set out in a nearly 100-year-old precedent, Gold Seal Ltd v Attorney- General for the Province of Alberta,5 albeit amending its interpretation of section 121 to prohibit both tariffs and “tariff-like” barriers. The Supreme Court also criticized the trial judge’s failure to respect stare decisis in overturning this precedent. -

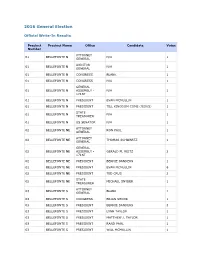

2016 General Write-In Results

2016 General Election Official Write-In Results Precinct Precinct Name Office Candidate Votes Number ATTORNEY 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL AUDITOR 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS BLANK 1 01 BELLEFONTE N CONGRESS N/A 1 GENERAL 01 BELLEFONTE N ASSEMBLY - N/A 1 171ST 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 1 01 BELLEFONTE N PRESIDENT TILL KINGDOM COME (JESUS) 1 STATE 01 BELLEFONTE N N/A 1 TREASURER 01 BELLEFONTE N US SENATOR N/A 1 ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE RON PAUL 1 GENERAL ATTORNEY 02 BELLEFONTE NE THOMAS SCHWARTZ 1 GENERAL GENERAL 02 BELLEFONTE NE ASSEMBLY - GERALD M. REITZ 2 171ST 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 6 02 BELLEFONTE NE PRESIDENT TED CRUS 2 STATE 02 BELLEFONTE NE MICHAEL SNYDER 1 TREASURER ATTORNEY 03 BELLEFONTE S BLANK 1 GENERAL 03 BELLEFONTE S CONGRESS BRIAN SHOOK 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 3 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT LYNN TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT MATTHEW J. TAYLOR 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT RAND PAUL 1 03 BELLEFONTE S PRESIDENT WILL MCMULLIN 1 ATTORNEY 04 BELLEFONTE SE JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 GENERAL 04 BELLEFONTE SE CONGRESS JORDAN D. DEVIER 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BERNIE SANDERS 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT BURNEY SANDERS/MICHELLE OBAMA 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT DR. BEN CARSON 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT ELEMER FUDD 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLAN 1 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT EVAN MCMULLIN 2 04 BELLEFONTE SE PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER/GEORGE M.W. -

225 Watertight Compartments: Getting Back to the Constitutional Division of Powers I. Introduction

GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS 225 WATERTIGHT COMPARTMENTS: GETTING BACK TO THE CONSTITUTIONAL DIVISION OF POWERS ASHER HONICKMAN* This article offers a fresh examination of the constitutional division of powers. The author argues that sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 establish exclusive jurisdictional spheres — what the Privy Council once termed “watertight compartments.” This mutual exclusivity is emphasized and reinforced throughout these sections and leaves very little room for legitimate overlap. While some degree of overlap is permissible under this scheme — particularly incidental effects, genuine double aspects, and limited ancillary powers — overlap must be constrained in a principled fashion to comply with the exclusivity principle. The modern trend toward flexibility and freer overlap is contrary to the constitutional text. The author argues that while some deviation from the text is inevitable due to the presumption of constitutionality and stare decisis, the Supreme Court should return to a more exclusivist footing in accordance with the text. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 226 II. THE EXCLUSIVITY PRINCIPLE .................................. 227 A. FROM QUEBEC TO THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT ................. 227 B. THE NON OBSTANTE CLAUSE AND THE DEEMING PROVISION ...... 231 C. CONCURRENT POWERS ................................... 234 III. PITH AND SUBSTANCE AND LEGITIMATE OVERLAP ................. 235 A. INTERJURISDICTIONAL IMMUNITY .........................