E-Government Interoperability: Guide UD GU I D E E-Government Interoperability: Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Conceptual Model for an E-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa

Towards a Conceptual Model for an e-Government Interoperability Framework for South Africa Paula Kotzé1,2 and Ronell Alberts1 1CSIR Meraka Institute, Pretoria, South Africa 2Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa Keywords: e-Government, e-GIF, Interoperability. Abstract: In September 2016, the South African Government published a White Paper on the National Integrated ICT Policy highlighting some principles for e-Government and the development of a detailed integrated national e-Government strategy and roadmap. This paper focuses on one of the elements of such a strategy, namely the delivery infrastructure principles identified, and addresses the identified need for centralised coordination to ensure interoperability. The paper proposes a baseline conceptual model for an e- Government interoperability framework (e-GIF) for South Africa. The development of the model considered best practices and lessons learnt from previous national and international attempts to design and develop national and regional e-GIFs, with cognisance of the South African legislation and technical, social and political environments. The conceptual model is an enterprise model on an abstraction level suitable for strategic planning. 1 INTRODUCTION (Lallana, 2008: p.1) and is becoming an increasingly crucial issue, also for developing countries (United Implementing a citizen-centric approach, digitising Nations Development Programme, 2007). Many processes and making organisational changes to governments have finalised the design of national e- delivering government services are widely posited as Government strategies and are implementing priority a way to enhance services, save money and improve programmes. However, many of these interventions citizens’ quality of life (Corydon et al., 2016). The have not led to more effective public e-services, term electronic government (e-Government) is simply because they have ended up reinforcing the commonly used to represent the use of digital tools old barriers that made public access cumbersome. -

Interoperability and Patient Access for Medicare Advantage Organization and Medicaid

Notice: This HHS-approved document has been submitted to the Office of the Federal Register (OFR) for publication and has not yet been placed on public display or published in the Federal Register. The document may vary slightly from the published document if minor editorial changes have been made during the OFR review process. The document published in the Federal Register is the official HHS-approved document. [Billing Code: 4120-01-P] DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 42 CFR Parts 406, 407, 422, 423, 431, 438, 457, 482, and 485 Office of the Secretary 45 CFR Part 156 [CMS-9115-P] RIN 0938-AT79 Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Interoperability and Patient Access for Medicare Advantage Organization and Medicaid Managed Care Plans, State Medicaid Agencies, CHIP Agencies and CHIP Managed Care Entities, Issuers of Qualified Health Plans in the Federally-facilitated Exchanges and Health Care Providers AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: This proposed rule is intended to move the health care ecosystem in the direction of interoperability, and to signal our commitment to the vision set out in the 21st Century Cures Act and Executive Order 13813 to improve access to, and the quality of, information that Americans need to make informed health care decisions, including data about health care prices CMS-9115-P 2 and outcomes, while minimizing reporting burdens on affected plans, health care providers, or payers. DATES: To be assured consideration, comments must be received at one of the addresses provided below, no later than 5 p.m. -

Interoperability and the Solaris™ 10 Operating System

Interoperability and the Solaris™ 10 Operating System Interoperability from the Desktop to the Data Center Across a Range of Systems, Software, and Technologies < Investment protection in heterogeneous environments Today, businesses rely on complex, geographically dispersed computing infrastructures that often consist of hundreds of heterogeneous hardware and software platforms from a wide variety of vendors. If these environments are to remain manageable, organizations must be able to rely on interoperable products that work well together. At the same time, as organiza- tions evolve their computing environments with an eye toward improving cost-effectiveness and total cost of ownership (TCO), heavy investments in servers, operating systems, and applications must be protected, and dependence on specific hardware or software vendors must be avoided. The Solaris™ 10 Operating System meets these challenges through a number of different ways, from interoperability with both Linux and Microsoft Windows-based systems through support for a wide range of open standards and open source applications. Interoperability with Java™ technology Windows on a Solaris system by installing a Highlights The Java™ technology revolution has changed SunPCi™ card. The Solaris OS also supports An ideal platform for heteroge- how people think about interoperability by open standards and interfaces that make it neous computing, the Solaris™ no longer tying application design to a specific easier to interoperate with Microsoft Windows 10 OS: platform. Running on every major hardware systems. Authentication interoperability can • Supports open standards such platform and supported by virtually every be achieved through the Kerberos protocol as UDDI, SOAP, WSDL, and XML software vendor, Java technology enables using the Sun Enterprise Authentication • Provides source and binary business applications to be developed and Mechanism™ software built right into the compatibility for Linux applica- operated independent of operating systems. -

Radical Interoperability Picking up Speed to Become a Reality for the Future of Health

FEATURE Radical interoperability Picking up speed to become a reality for the future of health Dave Biel, Mike DeLone, Wendy Gerhardt, and Christine Chang THE DELOITTE CENTER FOR HEALTH SOLUTIONS Radical interoperability: Picking up speed to become a reality for the future of health The future of health envisions timely and relevant exchange of health and other data between consumers, physicians, health care and life sciences organizations, and new entrants. What will it take for the industry to get there? Executive summary timely and relevant health and other data flowing between consumers, today’s health care Imagine a future in which clinicians, care teams, incumbents, and new entrants. This requires the patients, and caregivers have convenient, secure cooperation of the entire industry, including access to comprehensive health information hospitals, physicians, health plans, technology (health records, claims, cost, and data from companies, medical device companies, pharma medical devices) and treatment protocols that companies, and consumers. When will the industry consider expenses and social influencers of health start accelerating from today’s silos to this future? unique to the patient. Technology can aid in Our research suggests that despite a long journey preventing disease, identifying the need to adjust ahead, radical interoperability is picking up speed medications, and delivering interventions. and moving from aspiration to reality. Continuous monitoring can lead health care organizations to personalized therapies that In spring 2019, the Deloitte Center for Health address unmet medical needs sooner. And the Solutions surveyed 100 technology executives at “time to failure” can become shorter as R&D health systems, health plans, biopharma advancements, such as a continual real-world companies, and medtech companies and evidence feedback loop, will make it easier to interviewed another 21 experts to understand the identify what therapies will work more quickly in state of interoperability today. -

Interoperability Framework for E-Governance (IFEG)

Interoperability Framework for e-Governance (IFEG) Version 1.0 October 2015 Government of India Department of Electronics and Information Technology Ministry of Communications and Information Technology New Delhi – 110 003 Interoperability Framework for e-Governance (IFEG) in India Metadata of a Document S. Data elements Values No. 1. Title Interoperability Framework for e-Governance (IFEG) 2. Title Alternative Interoperability Framework for e-Governance (IFEG) 3. Document Identifier IFEG 4. Document Version, month, Version 1.0, Oct, 2015 year of release 5. Present Status Draft. 6. Publisher Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY), Ministry of Communications & Information Technology (MCIT), Government of India (GoI) 7. Date of Publishing October, 2015 8. Type of Standard Document Framework ( Policy / Framework / Technical Specification/ Best Practice /Guideline/ Process) 9. Enforcement Category Advisory (for all public agencies) ( Mandatory/ Recommended / Advisory) 10. Creator Department of Electronics and Information Technology (DeitY) 11. Contribut or DeitY, NIC. 12. Brief Description Purpose of Interoperability Framework for e- Governance (IFEG) is: • To provide background on issues and challenges in establishing interoperability and information sharing amongst e-Governance systems. • To describe an approach to overcome these challenges; the approach specifies a set of commonly agreed concepts to be understood uniformly across all e-Governance systems. • To offer a set of specific recommendations that can be adopted -

Introduction to Data Interoperability Across the Data Value Chain

Introduction to data interoperability across the data value chain OPEN DATA AND INTEROPERABILITY WORKSHOP DHAKA, BANGLADESH 28 APRIL – 2 MAY 2019 Main objectives of this session • Have a common understanding of key aspects of data interoperability • Discuss how data interoperability is fundamental to data quality and a precondition for open data • Discuss the foundations of data interoperability for national SDG data across the complete data value chain (from collection to use) ▪ Global vs local data needs ▪ Top-down vs bottom-up data producers The SDG data ecosystem is ▪ Structured data exchange vs organic characterized data sharing processes by multiple tensions ▪ Sectoral vs. Cross-cutting data applications Data interoperability challenge It’s difficult to share, integrate and work with the wealth of data that is available in today’s digital era: ▪ Divergent needs and capabilities of multiple internal and external constituencies ▪ Disparate protocols, technologies and standards ▪ Fragmented data production and dissemination systems Knowledge Value creation Interoperability is a characteristic of good quality data Fitness for Collaboration purpose Technology layer The Data and format layers interoperability Human layer challenge is multi-faceted Institutional and organisational layers Data interoperability for the SDGs There are many unrealized opportunities to extract value from data that already exists to meet information needs of the 2030 Agenda Investing time and resources in the development and deployment of data interoperability -

Using Metadata for Interoperability of Species Distribution Models

Proc. Int’l Conf. on Dublin Core and Metadata Applications 2015 Using Metadata for Interoperability of Species Distribution Models Cleverton Ferreira Borba Pedro Luiz Pizzigatti Corrêa University of Sao Paulo, Brazil University of Sao Paulo, UNASP, Brazil Brazil [email protected] [email protected] Keywords: Metadata, Species Distribution Modeling, Dublin Core, Darwin Core, architecture, interoperability. 1. Use of Metadata for Species Distribution Modeling (SDM) This poster presents the use of metadata patterns for the field of Species Distribution Modeling and also presents a proposal for application of metadata to ensure interoperability between models generated by tools of Species Distribution Modeling (SDM). According to Peterson et al. (2010) the area of Biodiversity Informatics is responsible, by the use of new technologies and computational tools, to meet the demand for support the biodiversity conservation. Portals of biodiversity, taxonomic databases, SDM tools help the scientists and researchers to decide the best for the biodiversity conservation. However, Berendsohn et al. (2011) says that one of the most serious problems in scientific biodiversity science is the need to integrate data from different sources, software applications and services for analysis, visualization and publication and thus offer an interoperability of data, information, application and tools. In this context, the metadata patterns available, has been used to help the scientists and researchers to define vocabulary and data structure for analysis, visualization and publication of biodiversity data. Examples of metadata used in SDM are: Dublin Core (DC) (DCMI, 2012), Darwin Core (DwC) (Wieczorek et al., 2012), Darwin Core Archive (DwC-A) (GBIF, 2010), EML – Ecological Metadata Language (Fegraus et al., 2005), etc. -

E-LEARNING INTEROPERABILITY STANDARDS CONTENTS

WHITE PAPER e-LEARNING INTEROPERABILITY STANDARDS CONTENTS THE VALUE OF e-LEARNING STANDARDS 1 TYPES OF e-LEARNING INTEROPERABILITY STANDARDS 2 Metadata 3 Content Packaging 4 Learner Profile 4 Learner Registration 5 Content Communication 5 SUN SUPPORT FOR e-LEARNING STANDARDS 6 Technical Architecture 6 Leadership in the Standards Community 6 STANDARDS DEVELOPMENT PROCESS 7 Specification 8 Validation 8 Standardization 8 e-LEARNING STANDARDS ORGANIZATIONS AND INITIATIVES 9 IMS Global Learning Consortium 9 Learning Object Metadata (LOM) 9 Content Packaging 10 Question and Test Interoperability (QTI) 10 Learner Information Packaging (LIP) 10 Enterprise Interoperability 10 Simple Sequencing 10 Learning Design 10 Digital Repositories 10 Competencies 11 Accessibility 11 Advanced Distributed Learning Initiative (ADL) 11 Sharable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) 11 Schools Interoperability Framework (SIF) 13 IEEE Learning Technology Standards Committee (LTSC) 13 Learning Object Metadata (LOM) 14 Other Initiatives 14 Aviation Industry CBT Committee (AICC) 14 Other Global Initiatives 15 CEN/ISSS Workshop on Learning Technology (WSLT) 15 ISO/IEC JTC1 SC36 15 Advanced Learning Infrastructure Consortium (ALIC) 15 Alliance of Remote Instructional and Distribution Networks for Europe (ARIADNE) 16 Education Network Australia (EdNA) 16 PROmoting Multimedia access to Education and Training in EUropean Society (PROMETEUS) 16 FUTURE DIRECTIONS IN STANDARDS 16 Expansion of Content Specifications and Reference Models 16 Content Repositories 16 Internationalization and Localization 16 Conformance and Compliance Testing 17 Architecture 17 REFERENCES 17 e-Learning Standards Organizations 17 Glossary of e-Learning Standards Acronyms 23 Other References 24 Footnotes 24 Sun Microsystems, Inc. i Interoperability among e-learning content and system components is a key to the successful implementation of an e-learning environ- ment. -

Open Standards Principles

Open Standards Principles: For software interoperability, data and document formats in government IT specifications ii OPEN STANDARDS PRINCIPLES: For software interoperability, data and document formats in government IT specifications #opengovIT iii iv Foreword Government IT must be open - open to the people and organisations that use our services and open to any provider, regardless of their size. We currently have many small, separate platforms operating across disconnected departments and IT that is tied into monolithic contracts. We need to have a platform for government that allows us to share appropriate data effectively and that gives us flexibility and choice. Already we have started to make progress and there is activity right across government that demonstrates our commitment to achieving the change we need. The Government Digital Service has launched GOV.UK - a simpler, clearer, faster and common platform for government's digital services, based on open source software. The whole site is designed around the needs of the user. GDS has also developed the online petitions system for the UK Parliament to enable people to raise, sign and track petitions. It was developed by SMEs and is built on open standards. Another site legislation.gov.uk – the online home of legislation – was designed around open standards so more participants could get involved. It connects with inhouse, public and private sector systems and has allowed The National Archives to develop an entirely new operating model for revising legislation. The private sector is investing effort in improving the underlying data. Companies then re- use the source code for processing the data and are including this in their own commercial products and services. -

An Economic Basis for Open Standards Flosspols.Org

An Economic Basis for Open Standards flosspols.org An Economic Basis for Open Standards Rishab A. Ghosh Maastricht, December 2005 This report was supported by the FLOSSPOLS project, funded under the Sixth Framework Programme of the European Union, managed by the eGovernment Unit of the European Commission's DG Information Society. Rishab Ghosh ([email protected]) is Programme Leader, FLOSS and Senior Researcher at the United Nations University Maastricht Economic and social Research and training centre on Innovation and Technology (UNU- MERIT), located at the University of Maastricht, The Netherlands Copyright © MERIT, University of Maastricht 1 An Economic Basis for Open Standards flosspols.org An Economic Basis for Open Standards Executive Summary This paper provides an overview of standards and standard-setting processes. It describes the economic effect of technology standards – de facto as well as de jure – and differentiates between the impact on competition and welfare that various levels of standards have. It argues that most of what is claimed for “open standards” in recent policy debates was already well encompassed by the term “standards”; a different term is needed only if it is defined clearly in order to provide a distinct economic effect. This paper argues that open standards, properly defined, can have the particular economic effect of allowing “natural” monopolies to form in a given technology, while ensuring full competition among suppliers of that technology. This is a distinct economic effect that deserves to be distinguished by the use of a separate term, hence “open” rather than “ordinary” standards – referred to as “semi-open” in this paper. -

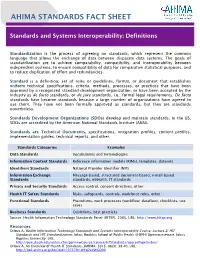

AHIMA Fact Sheet: Standards and Systems Interoperability Definitions

AHIMA STANDARDS FACT SHEET Standards and Systems Interoperability: Definitions Standardization is the process of agreeing on standards, which represent the common language that allows the exchange of data between disparate data systems. The goals of standardization are to achieve comparability, compatibility, and interoperability between independent systems, to ensure compatibility of data for comparative statistical purposes, and to reduce duplication of effort and redundancies. Standard is a definition, set of rules or guidelines, format, or document that establishes uniform technical specifications, criteria, methods, processes, or practices that have been approved by a recognized standard development organization, or have been accepted by the industry as de facto standards, or de jure standards, i.e., formal legal requirements. De facto standards have become standards because a large number of organizations have agreed to use them. They have not been formally approved as standards, but they are standards nonetheless. Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) develop and maintain standards. In the US, SDOs are accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). Standards are Technical Documents, specifications, integration profiles, content profiles, implementation guides, technical reports, and other. Standards Categories Examples Data Standards Vocabularies and terminologies Information Content Standards Reference information models (RIMs), templates, datasets Identifiers Standards National Provider Identifier (NPI) Information Exchange Message-based, structured document-based, e-mail-based Standards standards, mHealth, IT standards Privacy and Security Standards Access control, consent directives, other Health IT Safety Standards Risks, safeguards, controls, workforce roles, other Functional Standards Procedures, work processes (workflow, dataflow), checklists, use cases Business Standards Guidelines, best practices Source: Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP), 2005. -

Videoconferencing - Wikipedia,Visited the Free on Encyclopedia 6/30/2015 Page 1 of 15

Videoconferencing - Wikipedia,visited the free on encyclopedia 6/30/2015 Page 1 of 15 Videoconferencing From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Videoconferencing (VC) is the conduct of a videoconference (also known as a video conference or videoteleconference) by a set of telecommunication technologies which allow two or more locations to communicate by simultaneous two-way video and audio transmissions. It has also been called 'visual collaboration' and is a type of groupware. Videoconferencing differs from videophone calls in that it's designed to serve a conference or multiple locations rather than individuals.[1] It is an intermediate form of videotelephony, first used commercially in Germany during the late-1930s and later in A Tandberg T3 high resolution the United States during the early 1970s as part of AT&T's development of Picturephone telepresence room in use technology. (2008). With the introduction of relatively low cost, high capacity broadband telecommunication services in the late 1990s, coupled with powerful computing processors and video compression techniques, videoconferencing has made significant inroads in business, education, medicine and media. Like all long distance communications technologies (such as phone and Internet), by reducing the need to travel, which is often carried out by aeroplane, to bring people together the technology also contributes to reductions in carbon emissions, thereby helping to reduce global warming.[2][3][4] Indonesian and U.S. students Contents participating in an educational videoconference