And Permanent-Charge Soils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumohydrocalcite Caal2(CO3)2(OH)4 • 3H2O C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Triclinic

Alumohydrocalcite CaAl2(CO3)2(OH)4 • 3H2O c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Triclinic. Point Group: 1or1. As fibers and needles, to 2.5 mm; commonly in radial aggregates and spherulites, feltlike crystal linings, and powdery to chalky masses. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {100} perfect; {010} imperfect. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 2.5 D(meas.) = 2.21–2.24 D(calc.) = 2.213 Decomposes in boiling H2O to calcite and hydrous aluminum oxide. Optical Properties: Transparent to opaque. Color: Chalky white to pale blue, pale yellow, cream, gray; pale rose or brownish pink to dark violet in chromian varieties; colorless in transmitted light. Luster: Vitreous to pearly, earthy. Optical Class: Biaxial (–). Orientation: X = b; extinction inclined 6◦–10◦. α = 1.485–1.502 β = 1.553–1.563 γ = 1.570–1.585 2V(meas.) = 64◦ 2V(calc.) = 50◦–55◦ Cell Data: Space Group: P 1or P 1 (chromian). a = 6.498(3) b = 14.457(4) c = 5.678(3) α =95.83(5)◦ β =93.23(3)◦ γ =82.24(3)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany. 6.25 (100), 6.50 (70), 3.23 (60), 2.039 (50), 2.519 (40), 7.21 (30), 2.860 (30) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) (1) (2) (3) CO2 24.2 26.4 26.19 CaO 17.8 16.5 16.68 Al2O3 31.3 22.0 30.33 H2O 26.7 26.6 26.80 Cr2O3 8.3 Total 100.0 99.8 100.00 2− 1− (1) Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany; (CO3) , (OH) , and H2O confirmed by IR. -

Behaviour and Geotechnical Properties of Residual Soils and Allophane Clays

Wesley, L. (2009). Behaviour and geotechnical properties of residual soils and allophane clays. Obras y Proyectos 6, 5-10. Behaviour and geotechnical properties of residual soils and allophane clays Fecha de entrega: 20 de Septiembre 2009 Fecha de aceptación: 23 de Noviembre 2009 Laurie Wesley Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, the University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland, New Zealand, [email protected] An overview of the properties of residual soils is given in the first part En la primera parte del artículo se entrega una descripción general de of the paper. The different processes by which residual and sedimentary los suelos residuales. Se detallan los diferentes procesos en los cuales son soils are formed are described, and the need to be aware that procedures formados los suelos residuales y sedimentarios, poniendo hincapié en la applicable to sedimentary soils do not necessarily apply to residual soils necesidad de estar atento a que los procedimientos aplicados a los suelos is emphasised. In particular, it is shown that the log scale normally sedimentarios no son necesariamente aplicables a los suelos residuales. used for presenting oedometer test results is not appropriate or relevant En particular, se muestra que la escala logarítmica generalmente usada to residual soils. The second part of the paper gives an account of para presentar resultados de ensayos edométricos no es apropiada o the special properties of allophane clays. Their abnormally high water pertinente para suelos residuales. La segunda parte del artículo da content and Atterberg limits are described, and it is shown that despite cuenta de las propiedades especiales de arcillas alofánicas. -

Distribution and Classification of Volcanic Ash Soils

83 Distribution and Classification of Volcanic Ash Soils 1* 2 Tadashi TAKAHASHI and Sadao SHOJI 1 Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Tohoku University 1-1, Tsutsumidori, Amamiya-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai, 981-8555 Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Professor Emeritus, Tohoku University 5-13-27, Nishitaga, Taihaku-ku, Sendai, 982-0034 Japan *corresponding author Abstract Volcanic ash soils are distributed exclusively in regions where active and recently extinct volcanoes are located. The soils cover approximately 124 million hectares, or 0.84% of the world’s land surface. While, thus, volcanic ash soils comprise a relatively small extent, they represent a crucial land resource due to the excessively high human populations living in these regions. However, they did not receive worldwide recognition among soil scientists until the middle of the 20th century. Development of international classification systems was put forth by the 1978 Andisol proposal of G. D. Smith. The central concept of volcanic ash soils was established after the finding of nonallophanic volcanic ash soils in Japan in 1978. Nowadays, volcanic ash soils are internationally recognized as Andisols in Soil Taxonomy (United States Department of Agriculture) and Andosols in the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (FAO, International Soil Reference and Information Centre and International Society of Soil Science). Several countries including Japan and New Zealand have developed their own national classification systems for volcanic ash soils. Finally correlation of the international and domestic classification systems is described using selected volcanic ash soils. Key words: Andisols, Andosols, Japanese Cultivated Soil Classification, New Zealand Soil Classification, Soil Taxonomy, World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) 1. -

Boron Sorption and Release by Allophane Chunming Su* and Donald L

Reprinted from the Soil Science Society of America Journal Volume61,no.. 1,January-Februaryy 1997 677 South Segoe Rd., Madison, WI 53711 USA Boron Sorption and Release by Allophane Chunming Su* and Donald L. Suarez ABSTRACT fully understood. Insight into mechanisms controlling B To predict B behavior in soils and its influence on plants, it is partitioning between solid and solution phases is crucial crucial to understand the mechanisms of B sorption by mineral phases. for a quantitative understanding of B behavior in soils Because B reacts with clay minerals and Al and Fe oxides, it should and its effects on plants. also sorb to poorly crystalline aluminosilicates such as allophane. Boron In this study, the term sorption is defined as the attach- sorption, with and following allophane precipitation, was studied in ment of species to a solid. The sorption phenomena batch experiments. Solutions containing AICIJ and NazSiOa (concentra- include the processes of adsorption, coprecipitation, and tions <47 mM with Al/Si molar ratio of 1:1) and B(OHh (0, 4.4, and inclusion. Adsorption is the process through which a net 32 mM) were mixed and titrated to pH 8.0 with 1 M NaOH at two accumulation of a substance occurs at the interface of rates (1 and 5 mL mitt-‘) at 23”C, then incubated at 23 and 90° C for 5 d. More B was removed from solution when B was present two phases, whereas coprecipitation is isomorphic substi- during allophane precipitation than when B of an equal concentration tution of one ion for another of comparable radius in a was reacted with freshly precipitated allophane. -

Adsorption and Fixation by Clay Mineral

Long‐term Behavior of Radioactive Cesium in the Environment: Effects Adsorption and Fixation by Clay Mineral Adsorption and fixation of cesium Fig. 14 A clay mineral that does not fix cesium A clay mineral that strongly fixes so much (montmorillonite, etc.) cesium (vermiculite, illite, etc.) Adsorption Fixation Layered structure Adsorption of a clay mineral Layered structure Interlayer Cesium of a clay mineral Cesium Adsorption Adsorption [Explanation] Long-term Effects 4.4 ・A clay mineral on its surface has a negative charge and can adsorb cesium and part of the clay mineral can also incorporate and fix cesium in itself over time. ・Adsorbed cesium can be absorbed by plants, but once fixed, not so much is absorbed. Table 4 Soil components Adsorption of Cs Fixation of Cs Soil organic matters Strong Weak Clay minerals (non‐micaceous) Kaolinite, Halloysite Strong Weak [Explanation] Allophane, Imogolite Strong Weak to medium ・Soil organic matters and non‐ Montmorillonite Strong Weak micaceous clay minerals, such as montmorillonite, have weak fixation Clay minerals (micaceous) power. Vermiculite Strong Strong ・Micaceous clay minerals, such as Illite Strong Medium to strong vermiculite and illite, strongly fix Aluminum vermiculite Strong Medium to strong cesium. Zeolite Strong Strong (Note) (Note) Anchoring power of these components vary depending on production areas and qualities. Source: From the following website: http://www.maff.go.jp/j/kanbo/joho/saigai/pdf/youin_kome2.pdf (in Japanese) Cesium has a similar chemical property as potassium, etc. (having a positive charge) and can be easily adsorbed by clay minerals that have a negative charge superficially. Furthermore, some clay minerals have the ability to fix cesium that they have adsorbed, as time proceeds. -

Allophane Al O ² 1:3 2:0(Sio ) ² 2:5 3:0(H O) 2 3 ¡ 2 ¡ 2 C 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Amorphous (?)

Allophane Al O ² 1:3 2:0(SiO ) ² 2:5 3:0(H O) 2 3 ¡ 2 ¡ 2 c 2001 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1.2 ° Crystal Data: Amorphous (?). Point Group: n.d. Rarely observed as ring-shaped particles, with diameters of 50 Aº, which in three dimensions may represent sections through hollow spherules or polyhedra. As hyaline crusts and masses; stalactites and °owstones. Physical Properties: Fracture: Conchoidal to earthy. Tenacity: Brittle. Hardness = 3 D(meas.) = 2.75 D(calc.) = n.d. Optical Properties: Translucent. Color: White, pale blue to sky-blue, green, brown. Luster: Vitreous to earthy, waxy. Optical Class: Isotropic. n = 1.468{1.512 (air-dried). Cell Data: Space Group: n.d. Z = n.d. X-ray Powder Pattern: n.d. Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) (1) (2) (3) SiO2 21.39 28.31 29.17 CaO 1.96 trace trace TiO2 0.40 0.42 Na2O 1.91 1.48 Al2O3 35.20 34.41 33.81 K2O 0.29 0.16 + Fe2O3 0.56 0.56 H2O 40.86 10.60 11.20 MgO 0.08 0.04 H2O¡ 23.20 23.00 Total 99.41 99.76 [99.84] (1) Allentown, Lehigh Co., Pennsylvania, USA; CaO as (Ca; Mg)CO3: (2) Iijima, Japan. (3) Kanuma, Japan; original total given as 99.81%. Occurrence: A weathering product of volcanic ash. In hydrothermally altered igneous rocks, from the breakdown of feldspars, and in hydrothermal veins, typically related to copper deposits. In sedimentary rocks, including chalk and coal beds. Association: Quartz, cristobalite, imogolite, gibbsite, vermiculite, chrysocolla, \limonite". Distribution: Of widespread occurrence. -

Clay Minerals

CLAY MINERALS CD. Barton United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Aiken, South Carolina, U.S.A. A.D. Karathanasis University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION of soil minerals is understandable. Notwithstanding, the prevalence of silicon and oxygen in the phyllosilicate structure is logical. The SiC>4 tetrahedron is the foundation Clay minerals refers to a group of hydrous aluminosili- 2 of all silicate structures. It consists of four O ~~ ions at the cates that predominate the clay-sized (<2 |xm) fraction of apices of a regular tetrahedron coordinated to one Si4+ at soils. These minerals are similar in chemical and structural the center (Fig. 1). An interlocking array of these composition to the primary minerals that originate from tetrahedral connected at three corners in the same plane the Earth's crust; however, transformations in the by shared oxygen anions forms a hexagonal network geometric arrangement of atoms and ions within their called the tetrahedral sheet (2). When external ions bond to structures occur due to weathering. Primary minerals form the tetrahedral sheet they are coordinated to one hydroxyl at elevated temperatures and pressures, and are usually and two oxygen anion groups. An aluminum, magnesium, derived from igneous or metamorphic rocks. Inside the or iron ion typically serves as the coordinating cation and Earth these minerals are relatively stable, but transform- is surrounded by six oxygen atoms or hydroxyl groups ations may occur once exposed to the ambient conditions resulting in an eight-sided building block termed an of the Earth's surface. Although some of the most resistant octohedron (Fig. -

Methods for Characterizing Adobe Building Materials

..i^^ °' Cc \ a NBS TECHNICAL NOTE 977 ^'"Jeau o* U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/National Bureau of Standards Methods For Characterizing ^ Adobe Building IVIaterials 3 977 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for pubUc benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is performed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government Agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference -

Allophane and Imogolite: Role in Soil Biogeochemical Processes

Clay Minerals, (2009) 44, 135–155 GEORGE BROWN LECTURE 2008 Allophane and imogolite: role in soil biogeochemical processes R. L. PARFITT* Landcare Research, PB 11052, Palmerston North, New Zealand (Received 18 November 2008; revised 18 March 2009; Editor: Balwant Singh) ABSTRACT: The literature on the formation, structure and properties of allophane and imogolite is reviewed, with particular emphasis on the seminal contributions by Colin Farmer. Allophane and imogolite occur not only in volcanic-ash soils but also in other environments. The conditions required for the precipitation of allophane and imogolite are discussed. These include pH, availability of Al and Si, rainfall, leaching regime, and reactions with organic matter. Because of their excellent water storage and physical properties, allophanic soils can accumulate large amounts of biomass. In areas of high rainfall, these soils often occur under rain forest, and the soil organic matter derived from the forest biomass is stabilized by allophane and aluminium ions. Thus the turnover of soil organicmatter in allophanicsoils is slower than that in non-allophanicsoils. The organicmatter appears to be derived from the microbial by-products of the plant material rather than from the plant material itself. The growth of young forests may be limited by nitrogen supply but growth of older forests tends to be P limited. Phosphorus is recycled through both inorganic and organic pathways, but it is also strongly sorbed by Al compounds including allophane. When crops are grown in allophanic soils, large amounts of labile P are required and, accordingly, these soils have to be managed to counteract the large P sorption capacity of allophane and other Al compounds, and to ensure an adequate supply of labile P. -

Unique but Diverse: Some Observations on the Formation, Structure, and Morphology of Halloysite

Reference: Churchman, G.J., Pasbakhsh, P., Lowe, D.J., Theng, B.K.G. 2016. Unique but diverse: some observations on the formation, structure, and morphology of halloysite. Clay Minerals 51, 395-416. Unique but diverse: some observations on the formation, structure and morphology of halloysite. 1* 2 3 4 G.J. CHURCHMAN , P. PASBAKHSH , D.J. LOWE AND B.K.G. THEN G 1School of Agriculture, Food and Wine, University of Adelaide, Adelaide 5005, Australia, 2School of Engineering, Monash University, Selangor 47500, Malaysia,3 School of Science, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Waikato, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand, 4Landcare Research, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand Submitted: 4 November 2015. Revised: 11 June 2016. Guest Editor: Steve Hillier. ABSTRACT: New insights from the recent literature are summarised and new data presented concerning the formation, structure and morphology of halloysite. Halloysite formation by weathering always requires the presence of water. Where substantial drying occurs, kaolinite is formed instead. Halloysite formation is favoured by a low pH. The octahedral sheet is positively charged at pH < ~8, whereas the tetrahedral sheet is negatively hargedc at pH > ~2. The opposing sheet charge would facilitate interlayer uptake of H2O molecules. When halloysite intercalates certain polar organic molecules, additional (hkl) reflections appear in the X-ray diffractogram, suggesting layer re-arrangement which, however, is dissimilar to that in kaolinite. Associated oxides and oxyhydroxides of Fe and Mn may limit the growth of halloysite particles as does incorporation of Fe into the structure. Particles of different shape and iron content may occur within a given sample of halloysite. -

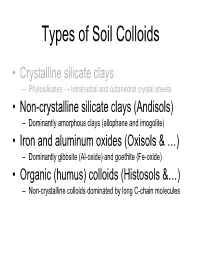

Types of Soil Colloids

Types of Soil Colloids • Crystalline silicate clays – Phylosilicates → tetrahedral and octahedral crystal sheets • Non-crystalline silicate clays (Andisols) – Dominantly amorphous clays (allophane and imogolite) • Iron and aluminum oxides (Oxisols & …) – Dominantly gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide) • Organic (humus) colloids (Histosols &…) – Non-crystalline colloids dominated by long C-chain molecules Non-crystalline Silicate Clays Allophane and Imogolite 1. Volcanic ash is chemically/mineralogically distinct from most other soil parent materials. 2. Composed largely of vitric or glassy materials containing varying amounts of Al and Si. 3. It lacks a well-defined crystal structure (i.e., amorphous) and is quite soluble. Allophane and Imogolite are common early-stage residual weathering products of volcanic glass and both have poorly-ordered structures. Allophane forms inside glass fragments where Si concentration and pH are high and has a characteristic spherule shape. Imogolite tends to form on the exterior of glass fragments under conditions of lower pH and Si concentration, and has a characteristic thread-like morphology. Iron and Aluminum oxides Sesquioxides Dominantly gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide) 1. Found in many soils 2. Especially important in highly weathered soils of warm humid regions 3. Consist of mainly either Fe or Al atoms coordinated with O atoms - the O atoms often associated with H ions to make hydroxyl groups 4. Some, such as gibbsite (Al-oxide) and goethite (Fe-oxide), form crystalline sheets 5. Others form amorphous coatings on soil particles Because of surface plane of covalently bonded hydroxyls gives these colloids the capacity to strongly adsorb certain anions Because of surface plane of covalently bonded hydroxyls gives these colloids the capacity to strongly adsorb certain anions Gibbsite (Al-oxide) Goethite (Fe-oxide) amorphous coatings on soil particles Organic (humus) colloids Non-crystalline colloids dominated by long C-chain molecules 1. -

Aqueous Solubility Studies of High-Alumina and Clay Minerals

THE AMERICAN MINERALOGIST, VOL. 53, MAY_JUNE, 1968 AQUEOUS SOLUBILITY STUDIES OF HIGH-ALUMINA AND CLAY MINERALS A. L. Rnpsu *lN,rDepartment of Geology,Western Michigan Uniaersily' Kalamozoo,M ichi'gon4900 1 AND W. D. Knllon, Department oJ Geology,Univers'ity of Missouri, Columbia, M issouri, 65 20 1. Assrnecr the same system. Our best values for standard free energies of formation are: - Dickite 904.4+O.7kcal/F.W. - Kaolinite (in ball clay) 904.0+0.2kcal/F.W. - (variable) "Fire clay mineral" 900 to 904 - Halloysite 899+1.0 kcal/F.W. - Endellite 902.3+ O.7 kcal/AbSirOs(OH)r -127+.4+0.6 Montmorillonite (Cheto) kcal/F.W. -1270 Montmorillonite (CIay SPur) + 1.2 kcal/F'W. - etc' Gibbsite 550.3+0.4kcal/Alzos'3HzO - Boehmite 435.2 +0. 5 kcal/AlrOa'HzO - Diaspore 437.2+0.8 kcai/AlzOa'HzO -1258.7+0.8 Pyrophyllite kcal/F'W. -1327 Muscovite (only 1 samPlerun) INrnouucrroN This study is concerned with the dissolution of high-alumina minerals for and clay minerals shaken in distilled water at room temperature deter- periodsirom 3 to 1000 days. It included three objectives:(1) to clay mine the products of the aqueous dissolution of high alumina and and minerals, (Z; to d.t.r-ine solubility constants (Ks) of the minerals, (3) to calculate standard free energiesof formation (AFt') for the various minerals from the analytical data of the aqueoussolutions' Lasonnronv Procnorrnr by prior to dissolution in double-distilled water, mineral samples were disaggregated of the clay during three procedures. The preferred method, which was by simple slaking yields dissolution data agitation in water, is least destructive of the original clay crystals and Tennessee.