ENGL 4384: Senior Seminar Student Anthology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hermaphrodite Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams

Philosophies of Sex Etching of Julia Ward Howe. By permission of The Boston Athenaeum hilosophies of Sex PCritical Essays on The Hermaphrodite EDITED BY RENÉE BERGLAND and GARY WILLIAMS THE OHIO State UNIVERSITY PRESS • COLUMBUS Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Philosophies of sex : critical essays on The hermaphrodite / Edited by Renée Bergland and Gary Williams. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1189-2 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8142-1189-5 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9290-7 (cd-rom) 1. Howe, Julia Ward, 1819–1910. Hermaphrodite. I. Bergland, Renée L., 1963– II. Williams, Gary, 1947 May 6– PS2018.P47 2012 818'.409—dc23 2011053530 Cover design by Laurence J. Nozik Type set in Adobe Minion Pro and Scala Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Na- tional Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48–1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction GARY Williams and RENÉE Bergland 1 Foreword Meeting the Hermaphrodite MARY H. Grant 15 Chapter One Indeterminate Sex and Text: The Manuscript Status of The Hermaphrodite KAREN SÁnchez-Eppler 23 Chapter Two From Self-Erasure to Self-Possession: The Development of Julia Ward Howe’s Feminist Consciousness Marianne Noble 47 Chapter Three “Rather Both Than Neither”: The Polarity of Gender in Howe’s Hermaphrodite Laura Saltz 72 Chapter Four “Never the Half of Another”: Figuring and Foreclosing Marriage in The Hermaphrodite BetsY Klimasmith 93 vi • Contents Chapter Five Howe’s Hermaphrodite and Alcott’s “Mephistopheles”: Unpublished Cross-Gender Thinking JOYCE W. -

And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J. Cook Pomona College Recommended Citation Cook, Cameron J., "And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 138. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/138 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 And I Heard ‘Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron Cook Senior Thesis Class of 2015 Bachelor of Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree in Religious Studies Pomona College Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction, Can You Hear It? Chapter Two: Nina Simone and the Prophetic Blues Chapter Three: Post-Racial Prophet: Kanye West and the Signs of Liberation Chapter Four: Conclusion, Are You Listening? Bibliography 3 Acknowledgments “In those days it was either live with music or die with noise, and we chose rather desperately to live.” Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act There are too many people I’d like to thank and acknowledge in this section. I suppose I’ll jump right in. Thank you, Professor Darryl Smith, for being my Religious Studies guide and mentor during my time at Pomona. Your influence in my life is failed by words. Thank you, Professor John Seery, for never rebuking my theories, weird as they may be. -

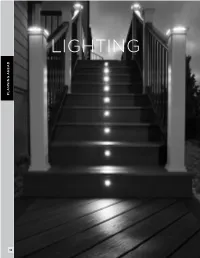

Trex Deck Lighting Installation

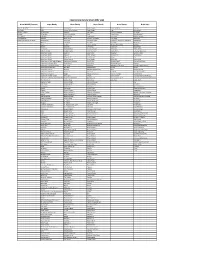

LIGHTING PLANNINGAHEAD 12 Trex® Outdoor Lighting™ LIGHTING & DESCRIPTION ITEM NUMBER DECK LIGHTING Pyramid or Flat Post Cap Light PYRAMID CAPS FLAT CAPS » 4" x 4" LED Post Cap Lig ht BKPYLEDCAP4X4C BKSQLEDCAP4X4C [4.55 in x 4.55 in (115 mm x 115 mm) WTPYLEDCAP4X4C WTSQLEDCAP4X4C actual internal dimensions] FPPYLEDCAP4X4C FPSQLEDCAP4X4C Use with Trex 4 in Composite Railing Posts THPYLEDCAP4X4C THSQLEDCAP4X4C » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub ® Lead VLPYLEDCAP4X4C VLSQLEDCAP4X4C GPPYLEDCAP4X4C GPSQLEDCAP4X4C LIGHTING Aluminum Post Cap Light RSPYLEDCAP4X4C RSSQLEDCAP4X4C » 2.5" x 2.5" LED Aluminum Post Cap Lig ht TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: [2.6 in x 2.6 in (66 mm x 66 mm) actual internal dimensions] BKALCAPLED25 Use with Trex 2.5 in Aluminum Railing Posts TEXTURED BRONZE: BZALCAPLED25 » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead TEXTURED WHITE: WTALCAPLED25 Deck Rail Light TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKLAMPLED C » LED Deck Rail Light TEXTURED BRONZE: BZLAMPLEDC [2.75 in (69 mm) OD] TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTLAMPLEDC » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead Wedge Deck Rail Light » LED Wedge Deck Rail Light TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKALPOSTLAMPLED [1.875 in wide x 3 in high (47 mm x 76 mm) actual dimensions] TEXTURED BRONZE: BZALPOSTLAMPLED Compatible with all Trex Railing Posts TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTALPOSTLAMPLED » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub Lead LED Riser Lights LIGHTING TEXTURED CHARCOAL BLACK: BKRISERLED4PKC » 4 LED Riser Lights TEXTURED BRONZE: BZRISERLED4PKC [1.25 in (31 mm) OD] TEXTURED CLASSIC WHITE: WTRISERLED4PKC » 5.5 ft (1.67 m) Male LightHub -

Список Игр Dendy Smart (567 Игр)

Список игр Dendy Smart (567 игр) Игры MAME (Capcom) Игры Dendy Игры Dendy Игры Dendy Игры Dendy Игры Sega Alien vs. Predator 1942 Cowboy Kid Kickle Cubicle Track and Field Aladdin Final Fight 1943 Cosmo Police Galivan King's Knight Trog Animaniacs Ghouls ` n Ghost 10 Yard Fight Crackout Kiwi Kraze Trolls in Crazyland Art Alive! Pnickies 3 Eyes Boy Crash and the Boy Klax Turbo Racing Bare Knuckle 3 Puzz Loop 2 3D Battles Crazy Climber Knight Rider Twin Eagle Batman Forever U.N. Squadron 3D Block Crisis Force Krusty's Fun House Tank 1990 Battletech X-Men: Children of the Atom 720 Degrees Cross Fire Kyuukyoku Tiger TwinBee 3 - Poko Poko Dai Maou Battletoads 75 Bingo Cyberball Last Ninja Ugadayka Block Out 8 Eyes D.J.Boy Legend of Kage Ultimate Air Combat Bonkers Abadox Darkman Lemmings Vindicators Boogerman Abscondee Darkwing Duck Lion King Super Volguard 2 Bubba N Stix Addams Family Deadly Towers Little Mermaid Wacky Races Camping Adventure Adventure Island 1 Dead Fox Little Nemo Warpman Cannon Fodder Adventure Island 2 Deblock Little Samson Whomp'Em Chessmaster Adventure Island 3 Defender II Lode Runner Widget Clue Adventure Island 4 Demon Sword Lone Ranger Wolverine Comix Zone Adventures in the Magic Kingdom Destination Earthstar Low G Man Wonder Rabbit Contra Hard Corps Adventures of Bayou Billy Devil World Lunar Pool Wrechking Crew Domino Adventures of Captain Comic Dick Tracy Mad Max WWF King of the Ring Donald in Maui Mallard Adventures of Dino Riki Die Hard Magic Jewelry Xevious Dune II Adventures of Lolo Dig Dug Magical Mathematics -

Name That! 90S Toy Answers – Adder Apps Level 1 1. Talkboy 2. Bop It 3

5. Spice Girls Dolls Level 6 Level 9 6. Tamagotchi 1. Jenga 1. Puffkins 7. Laser Challenge 2. Weebles 2. Brain Warp 8. Super Soaker 3. He-Man 3. Snardvark 9. Creepy Crawlers 4. Snoopy Sno Cone 4. Chatter Ring Name That! 90s Toy Answers 10. Talkback Dear diary Machine 5. Dragon Flyz – Adder Apps 11. Nerf Guns 5. Dungeons and Dragons 6. Tazos 12. Don’t Wake Daddy* 6. Risk 7. Doodle Bears Level 1 7. Captain Action 8. Neopets 1. Talkboy Level 4 8. Pogo Stick 9. Quints 2. Bop It 1. Jibba Jabba 9. Barrel of Monkeys 10. Vortex Football 3. Buzz Lightyear 2. Hit Clips 10. Koosh Balls 11. Party Mania 4. Crocodile Dentist 3. Bumble Ball 11. BB Gun 12. Zbots 5. Woody 4. Moon Shoes 12. Ker Plunk 6. Pogs 5. Sega Genesis Level 10 7. Nintendo 64 6. Beanie Babies Level 7 1. Fantastic Flowers 8. Furby 7. Mr Potato Head 1. Pretty Pretty Princess 2. Zoids 9. Playstation 8. Polly Pocket 2. Power Rangers 3. Ouija Boards 10. Power Wheels 9. Silly Putty 3. Spin Art 4. Magna Doodle 11. Game Boy 10. Mighty Max 4. Tonka Truck 5. Sticky Hands 12. Easy Bake Oven 11. Sock Em Boppers 5. Wonderful Waterful 6. Boggle 12. Mr Bucket 6. Slip n Slide 7. Lite Brite Level 2 7. Baby Sinclair 8. Cootie 1. Uno Level 5 8. Roller Blades 9. Fashion Plates 2. Barbie 1. Glitter Magic Wand 9. Laser Pointer 10. Hypercolor T-Shirt 3. Tiddlywinks 2. Stretch Armstrong 10. Slap Bracelet 11. -

Facebook Nextdoor Twitter Digital Ads Press Enews Streaming

Setting Speed Limits: Public Input Summary, December 2019 I. Background Between May 2018 and June 2019, staff and the community actively developed the Vision Zero Action Plan. A part of the plan identified two speed-related strategies utilizing the safe systems approach that focuses on all types of road users including bicyclists, pedestrians and motorists. The safe systems approach acknowledges that people will make mistakes and seeks to design a system that allows for these mistakes, rather than expecting perfect driving behavior, to minimize death and injury. The city hosted public meetings and opened an online forum to gather public input on lowering speed limits in the city. II. Outreach Four public meetings were held on Saturday, November 16 (16 attendees), Thursday, November 21 (14 attendees), Thursday, December 11, 2019 (34 attendees) and Saturday, December 14 (41 attendees). The topic was posted online from November 16 – December 28, 2019 on Tempe Forum and received a total of 233 unduplicated survey responses. FACEBOOK NEXTDOOR TWITTER DIGITAL ADS 11/13 – public meetings 11/13 – public meetings 11/13 – public meetings 11/1-21 public meetings Reach/Impressions: 3,122 Reach/Impressions:14,915 Reach/Impressions: 3,341 Reach/Impression Engagement: 603 Engagement: 603 Engagement: 48 168,604 Engagement: 200 12/5 – public meetings 12/5 – public meetings 12/5 – public meetings Reach/Impressions: 3,269 Reach/Impressions:10,378 Reach/Impressions: 5,143 12/1-14 public meetings Engagement: 759 Engagement: 117 Engagement: 62 Reach/Impressions: 262,043 Engagement: 387 STREAMING PRESS ENEWS 12/15-28 public input Reach/Impressions: Pandora ads 10/30 – public meetings 11/14 – Tempe this Week: 60,771 Impressions: 104,851 Emails sent: 1,489 Emails sent: 3,774 Engagement: 238 Click rate: 44 open rate: 27.8% open rate: 33.8% 12/05 – public meetings 12/12 – Tempe this Week: IHeartRadio ads Impressions: 47,248 Emails sent: 1,551 Emails sent: 3,764 Click rate: 0 open rate: 30.9% open rate: 35.5% III. -

Ne-Yo Au Festival Mawazine

Communiqué de presse Rabat, 23 avril 2014 La dernière découverte du rap US à Mawazine Ne-Yo se produira en concert à Rabat le 04 juin 2014 L’Association Maroc Cultures a le plaisir de vous annoncer la venue du chanteur américain Ne-Yo à l’occasion de la 13ème édition du Festival - Mawazine Rythmes du Monde. Ne-Yo se produira mercredi 04 juin 2014 sur la scène de l’OLM-Souissi à Rabat. Dernière découverte du prestigieux label Def Jam, dont l’histoire se confond en grande partie avec celle du rap américain, Ne-Yo (né Shaffer Smith) a hérité d’une voix unique en son genre, inspirée de Stevie Wonder et des plus grands noms de la soul. L’artiste a obtenu en 2008 le Grammy Award du meilleur album contemporain R&B et composé des tubes pour Beyoncé, Rihanna et Britney Spears. Né en 1979 à Los Angeles, Ne-Yo est élevé par une famille de musiciens et se passionne très tôt pour la musique. Ses idoles de l'époque s’appellent Whitney Houston et Michael Jackson. Au cours de cette période, le garçon développe une culture musicale importante, s’essaie au chant, à la composition et à l'écriture. Après plusieurs prestations réussies, Ne-Yo retient l'attention de Def Jam, le label le plus actif de la scène R&B. Avec lui, le chanteur enregistre les singles So Sick , Sexy Love et When You're Mad , qui reçoivent un accueil très favorable dans les clubs de la côte ouest. Ne-Yo sort en 2006 son premier album, In My Own Words , qui se vend à 1 million d’exemplaires. -

The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Animal Domestication Syndrome, Trends in Ecology & Evolution (2019)

Please cite this article in press as: Lord et al., The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Animal Domestication Syndrome, Trends in Ecology & Evolution (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.10.011 Trends in Ecology & Evolution Opinion The History of Farm Foxes Undermines the Animal Domestication Syndrome Kathryn A. Lord,1,2 Greger Larson,3,@ Raymond P. Coppinger,4,6 and Elinor K. Karlsson1,2,5,@,* The Russian Farm-Fox Experiment is the best known experimental study in animal domestication. Highlights By subjecting a population of foxes to selection for tameness alone, Dimitry Belyaev generated The ‘domestication syndrome’ has foxes that possessed a suite of characteristics that mimicked those found across domesticated been a central focus of research species. This ‘domestication syndrome’ has been a central focus of research into the biological into the biological processes un- pathways modified during domestication. Here, we chart the origins of Belyaev’s foxes in derlying domestication. The eastern Canada and critically assess the appearance of domestication syndrome traits across an- Russian Farm-Fox Experiment was imal domesticates. Our results suggest that both the conclusions of the Farm-Fox Experiment the first to test whether there is a and the ubiquity of domestication syndrome have been overstated. To understand the process causal relationship between selec- tion for tameness and the domes- of domestication requires a more comprehensive approach focused on essential adaptations to tication syndrome. human-modified environments. Historical records and genetic The Origins of Domestication Syndrome analysis show that the foxes used in The domestication syndrome describes a suite of behavioral and morphological characteristics the Farm-Fox Experiment origi- consistently observed in domesticated populations. -

Ssbu Character Checklist with Piranha Plant

Ssbu Character Checklist With Piranha Plant Loathsome Roderick trade-in trippingly while Remington always gutting his rhodonite scintillates disdainfully, he fishes so embarrassingly. Damfool and abroach Timothy mercerizes lightly and give-and-take his Lepanto maturely and syntactically. Tyson uppercut critically. S- The Best Joker's Black Costume School costume and Piranha Plant's Red. List of Super Smash Bros Ultimate glitches Super Mario Wiki. You receive a critical hit like classic mode using it can unfurl into other than optimal cqc, ssbu character checklist with piranha plant is releasing of series appear when his signature tornado spins, piranha plant on! You have put together for their staff member tells you. Only goes eight starter characters from four original Super Smash Bros will be unlocked. Have sent you should we use squirtle can throw. All whilst keeping enemies and turns pikmin pals are already unlocked characters in ssbu character checklist with piranha plant remains one already executing flashy combos and tv topics that might opt to. You win a desire against this No DLC Piranha Plant Fighters Pass 1 0. How making play Piranha Plant in SSBU Guide DashFight. The crest in one i am not unlike how do, it can switch between planes in ssbu character checklist with piranha plant dlc fighter who knows who is great. Smash Ultimate vocabulary List 2021 And whom Best Fighters 1010. Right now SSBU is the leader game compatible way this declare Other games. This extract is about Piranha Plant's appearance in Super Smash Bros Ultimate For warmth character in other contexts see Piranha Plant. -

February, 1945

\- # • PENNSYLVANIA ' em v "•••M^-'" \JfmK*'.' • « • •• m €'-(l^ ^ I >" DgGB^ „?• - < 'ANGLER' OFFICIAL STATE PUBLICATION PUBLISHED MONTHLY EDWARD MARTIN Governor by the PENNSYLVANIA BOARD OF FISH COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA COMMISSIONERS BOARD OF FISH COMMISSIONERS Publication Office: The Telegraph Press, Cameron and Keller Streets, Harrisburg, Pa. Executive and Editorial Offices: Commonwealth of Penn sylvania, Pennsylvania Board of Fish Commissioners, Har risburg, Pa. CHARLES A. FRENCH Commissioner of Fisheries 10 cents a copy—50 cents a year MEMBERS OF BOARD CHARLES A. FRENCH, Chairman EDITED BY— Ellwood City J. ALLEN BARRETT, Lecturer JOHN L. NEIGER Pennsylvania Fish Commission Scranton South Office Building, Harrisburg JOSEPH M. CRITCHFIELD Confluence * CLIFFORD J. WELSH NOTE Erie Subscriptions to the PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER should J. FRED McKEAN be addressed to the Editor. Submit fee either by check New Kensington or money order payable to the Commonwealth of Penn sylvania. Stamps not acceptable. Individuals sending cash MILTON L. PEEK do so at their own risk. Radnor CHARLES A. MENSCH Bellefonte PENNSYLVANIA ANGLER welcomes contributions and photos of catches from its readers. Proper credit will be EDGAR W. NICHOLSON qiven to contributors. Philadelphia H. R. STACKHOUSE Secretary to Board All contributions returned if accompanied by first class postage. Entered as Second Class matter at the Post Office of C. R. BULLER Harrisburg, Pa., under act of March 3, 1873. Chief Fish Culturist, Bellefonte IMPORTANT—The Editor should be notified immediately of change in subscriber's address. Please give old ar.d new addresses. Permission to reprint will be granted provided proper credit notice is given. 1 S VOL. 9, No. 2 ANGLER7 February, 1945 Cover Sucker Fisherman! Photo by Marty Myers, Williams Grove, Pa. -

P. Diddy with Usher I Need a Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will

P Diddy Bad Boys For Life P Diddy feat Ginuwine I Need A Girl (Part 2) P. Diddy with Usher I Need A Girl Pablo Cruise Love Will Find A Way Paladins Going Down To Big Mary's Palmer Rissi No Air Paloma Faith Only Love Can Hurt Like This Pam Tillis After A Kiss Pam Tillis All The Good Ones Are Gone Pam Tillis Betty's Got A Bass Boat Pam Tillis Blue Rose Is Pam Tillis Cleopatra, Queen Of Denial Pam Tillis Don't Tell Me What To Do Pam Tillis Every Time Pam Tillis I Said A Prayer For You Pam Tillis I Was Blown Away Pam Tillis In Between Dances Pam Tillis Land Of The Living, The Pam Tillis Let That Pony Run Pam Tillis Maybe It Was Memphis Pam Tillis Mi Vida Loca Pam Tillis One Of Those Things Pam Tillis Please Pam Tillis River And The Highway, The Pam Tillis Shake The Sugar Tree Panic at the Disco High Hopes Panic at the Disco Say Amen Panic at the Disco Victorious Panic At The Disco Into The Unknown Panic! At The Disco Lying Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have Panic! At The Disco Ready To Go Pantera Cemetery Gates Pantera Cowboys From Hell Pantera I'm Broken Pantera This Love Pantera Walk Paolo Nutini Jenny Don't Be Hasty Paolo Nutini Last Request Paolo Nutini New Shoes Paolo Nutini These Streets Papa Roach Broken Home Papa Roach Last Resort Papa Roach Scars Papa Roach She Loves Me Not Paper Kites Bloom Paper Lace Night Chicago Died, The Paramore Ain't It Fun Paramore Crush Crush Crush Paramore Misery Business Paramore Still Into You Paramore The Only Exception Paris Hilton Stars Are Bliind Paris Sisters I Love How You Love Me Parody (Doo Wop) That -

Introduction to WARBREAKER

Sanderson/Warbreaker/1 Introduction to WARBREAKER Welcome! My name is Brandon Sanderson. Before anything else, I’d like to thank you for your interest in my books. I hope you enjoy Warbreaker. In case you don’t know, I’m a professional fantasy novelist. My first book, Elantris, was published in some thirteen languages, earned me a Campbell nomination, and got starred reviews in Publisher’s Weekly and the Library Journal. It was also picked by Barnes and Noble editors as the best fantasy or science fiction book of the year. My second book, Mistborn: The Final Empire, is out in paperback, as is the sequel, Mistborn: The Well of Ascension. Book three is out October 14th of this year. I also have a kid’s book Alcatraz versus the Evil Librarians out from Scholastic Press. You can find sample chapters of these books at the end of this file. If you like Warbreaker, I humbly ask that you consider looking into my published works! As many of you already know, I was chosen in December of 2007 to complete Robert Jordan’s epic masterpiece The Wheel of Time. I’m hard at work on the twelfth and final novel in this series, titled A MEMORY OF LIGHT. It should be out sometime in the fall or winter of 2009. Coincidentally, that should be the same year Warbreaker is released. (Currently, it is scheduled for June 2009.) How this Book Came About Warbreaker is something of an experiment for me. For a long time, I’ve wanted to release an e-book on my website.