A Very Small Ledge: a Personal Reflection Jessica Couch University of Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Longneck Bottle

Longneck Bottle Count: 64 Wall: 4 Level: Intermediate Choreographer: Alan Haywood (UK) - January 2008 Music: Longneck Bottle - Garth Brooks : (Album: The Ultimate Hits) Intro – quick start (4 seconds only), start on the word ‘bottle’ Section 1 L back, hold, rock back R, recover L, R forward lockstep, hold 1 - 2 Step back onto left, hold for one count 3 - 4 Rock back onto right, recover weight forward onto left 5 – 6 - 7 - 8 Step forward onto right, lock left behind right, right forward, hold for one count Section 2 L forward slow mambo, hold, triple ½ R, hold 1 – 2 – 3 - 4 Rock forward onto left, recover weight onto right, step left next to right, hold for one count 5 – 6 – 7 – 8 Make a ½ turn right stepping right left right, hold for one count (6 o’clock) Section 3 2 x slow vaudervilles 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 Cross step left over right, right side, touch left heel diagonally left, step left next to right 5 – 6 – 7 - 8 Cross step right over left, left side, touch right heel diagonally right, step right next to left Section 4 L forward slow mambo, hold, R behind, L ¼ L, ½ L, hold 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 Rock forward onto left, recover weight onto right, step left next to right, hold for one count 5 – 6 Step right behind left, step left ¼ left 7 - 8 Pivot ½ turn left stepping back onto right, hold for one count (9 o’clock) RESTART HERE WALLS 2 & 5 Section 5 L back, hold, rock back R, recover L, R side rock, recover L, cross R over, hold 1 - 2 Step back onto left, hold for one count 3 - 4 Rock back onto right, recover weight forward onto left 5 – 6 Rock right -

Master Song List Keyboardist for Hire

Ryan McNevin – Master Song List Keyboardist For Hire Updated: September 6, 2021 # 38 Special – Hold On Loosely 54/40 – I Go Blind A ACDC – Highway To Hell Alice Cooper – I Am Made Of You ACDC – If You Want Blood (You've Got It) Alice Cooper – I'm Eighteen ACDC – Thunderstruck Alice Cooper – No More Mr. Nice Guy ACDC – TNT Alice Cooper – Under My Wheels ACDC – You Shook Me All Night Long Alice Merton – No Roots Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Allman Brothers – Ramblin' Man Adele – Someone Like You Allman Brothers – Statesboro Blues Aerosmith – Amazing Allman Brothers – Whipping Post Aerosmith – Angel Amanda Marshall – Beautiful Goodbye Aerosmith – Come Together Amy Winehouse – Valerie Aerosmith – Dude (Looks Like A Lady) Anastacia – Sick And Tired Aerosmith – Just Feel Better April Wine – Enough Is Enough Aerosmith – Last Child April Wine – I Wouldn't Want To Lose Your Love Aerosmith – Sweet Emotion April Wine – Rock N' Roll Is A Vicious Game Airbourne – Live It Up April Wine – Roller Al Green – Let's Stay Together Autograph – Turn Up The Radio Alanis Morissette – Reasons I Drink Avicii – Wake Me Up Alannah Myles – Black Velvet Avril Lavigne – Birdie Alannah Myles – Still Got This Thing For You Avril Lavigne – Head Above Water Alan Jackson – Don't Rock The Jukebox Avril Lavigne – Let You Go Alan Parsons – Oh Life (There Must Be More) Avril Lavigne – Warrior Alan Parsons – Old And Wise Alan Parsons – Time Aldo Nova – Fantasy B B52s – Love Shack Ben E. King – Stand By Me BT Overdrive – Taking Care Of Business Ben Folds – Gone Bad Company – -

1998-03-14-Billboard-Page-0042.Pdf

Country ARTISTS & MUSIC TRAVIS MAKES DREAMWORKS DEBUT COUNTRY (Continued from page 42) Travis is also straightforward as to grandiose plans together, but this one's months of the Travis campaign began ********** his reason for leaving Warner Bros. last working." with the single in February and run year. "I try not to say bad things, but I John Rose, senior executive for sales through August, when Travis will just had trouble with some people at and marketing, says, "Radio loves receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Warners," he says. "I still have a lot of Randy because he represents a return Fame. In between will be a billboard on friends over there who will be my to traditional roots, and he's got that rec- Sunset Boulevard; scores of radio, TV CORNER friends for the rest of my life. But I had ognizable voice that they need on the air. and print appearances and interviews; trouble with the head of the label and The fans want that name recognition." a performance March 17 at the Nation- by Wade Jessen with the head of promotion. We couldn't Rose says the label is laying out a al Assn. of Record Manufacturers con- agree on the way things should be done, comprehensive plan for the album. ference; a fan -club tie -in with Gibson I N THE AMEN CORNER: With an increase of about 3,000 scans, the sound- I guess. The contract was up, and then "Luckily, the parent company gave us guitars; a truck -stop cross -promotion track to Robert Duvall's film "The Apostle" rises 36 -21 and snatches the the DreamWorks thing came up, so it time to put our company together to do with the movie "Black Dog" in April and Greatest Gainer ribbon on Billboard's Top Country Albums. -

Request List 619 Songs 01012021

PAT OWENS 3 Doors Down Bill Withers Brothers Osbourne (cont.) Counting Crows Dierks Bentley (cont.) Elvis Presley (cont.) Garth Brooks (cont.) Hank Williams, Jr. Be Like That Ain't No Sunshine Stay A Little Longer Accidentally In Love I Hold On Can't Help Falling In Love Standing Outside the Fire A Country Boy Can Survive Here Without You Big Yellow Taxi Sideways Jailhouse Rock That Summer Family Tradition Kryptonite Billy Currington Bruce Springsteen Long December What Was I Thinking Little Sister To Make You Feel My Love Good Directions Glory Days Mr. Jones Suspicious Minds Two Of A Kind Harry Chapin 4 Non Blondes Must Be Doin' Somethin' Right Rain King Dion That's All Right (Mama) Two Pina Coladas Cat's In The Cradle What's Up (What’s Going On) People Are Crazy Bryan Adams Round Here Runaround Sue Unanswered Prayers Pretty Good At Drinking Beer Heaven Eric Church Hinder 7 Mary 3 Summer of '69 Craig Morgan Dishwalla Drink In My Hand Gary Allan Lips Of An Angel Cumbersome Billy Idol Redneck Yacht Club Counting Blue Cars Jack Daniels Best I Ever Had Rebel Yell Buckcherry That's What I Love About Sundays Round Here Buzz Right Where I Need To Be Hootie and the Blowfish Aaron Lewis Crazy Bitch This Ole Boy The Divinyls Springsteen Smoke Rings In The Dark Hold My Hand Country Boy Billy Joel I Touch Myself Talladega Watching Airplanes Let Her Cry Only The Good Die Young Buffalo Springfield Creed Only Wanna Be With You AC/DC Piano Man For What It's Worth My Sacrifice Dixie Chicks Eric Clapton George Jones Time Shook Me All Night Still Rock And -

Radio Starz Karaoke Song Book

Radio Starz Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID Aerosmith Barenaked Ladies Angel RSZ613-12 What A Good Boy RSZ604-11 Baby, Please Don't Go RSZ613-01 When I Fall RSZ604-09 Back In The Saddle RSZ613-16 Beatles, The Big Ten Inch Record RSZ613-13 All You Need Is Love RSZ623-08 Cryin' RSZ613-17 And I Love Her RSZ623-06 Dream On RSZ613-04 And Your Bird Can Sing RSZ622-17 Dude (Looks Like A Lady) RSZ613-06 Another Girl RSZ621-16 I Don't Want To Miss A Thing RSZ613-10 Back In The USSR RSZ622-02 Jaded RSZ613-07 Birthday RSZ622-05 Janie's Got A Gun RSZ613-14 Can't Buy Me Love RSZ622-09 Last Child RSZ613-03 Come Together RSZ621-14 Love In An Elevator RSZ613-09 Day Tripper RSZ621-07 Mama Kin RSZ613-11 Do You Want To Know A Secret RSZ623-11 Same Old Song And Dance RSZ613-15 Don't Let Me Down RSZ623-09 Sweet Emotion RSZ613-05 Eight Days A Week RSZ623-05 Train Kept A Rollin' RSZ613-18 Eleanor Rigby RSZ622-13 Walk This Way RSZ613-08 From Me To You RSZ623-15 What It Takes RSZ613-02 Get Back RSZ622-04 Alanis Morissette Golden Slumbers, Carry That Weight, The End RSZ621-20 All I Really Want RSZ626-13 Good Day Sunshine RSZ621-06 Everything RSZ626-11 Hard Days Night, A RSZ623-03 Forgiven RSZ626-12 Hello Goodbye RSZ622-06 Hand In My Pocket RSZ626-05 Help! RSZ621-04 Hands Clean RSZ626-08 Helter Skelter RSZ622-08 Hands Clean RSZ626-08A Here, There & Everywhere RSZ623-18 Hands Clean RSZ626-08B Hey Jude RSZ622-01 Head Over Feet RSZ626-07 I Feel Fine RSZ622-10 Ironic RSZ626-02 I Saw Her Standing There RSZ621-01 Precious Illusions -

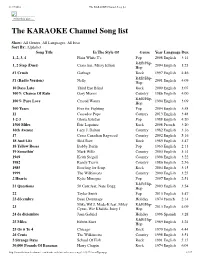

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

A 3Rd Strike No Light a Few Good Men Have I Never a Girl Called Jane

A 3rd Strike No Light A Few Good Men Have I Never A Girl Called Jane He'S Alive A Little Night Music Send In The Clowns A Perfect Circle Imagine A Teens Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens Can't Help Falling In Love With You A Teens Floor Filler A Teens Halfway Around The World A1 Caught In The Middle A1 Ready Or Not A1 Summertime Of Our Lives A1 Take On Me A3 Woke Up This Morning Aaliyah Are You That Somebody Aaliyah At Your Best (You Are Love) Aaliyah Come Over Aaliyah Hot Like Fire Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew Aaliyah Journey To The Past Aaliyah Miss You Aaliyah More Than A Woman Aaliyah One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah Rock The Boat Aaliyah Try Again Aaliyah We Need A Resolution Aaliyah & Tank Come Over Abandoned Pools Remedy ABBA Angel Eyes ABBA As Good As New ABBA Chiquita ABBA Dancing Queen ABBA Day Before You Came ABBA Does Your Mother Know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Manana ABBA Head Over Heels ABBA Honey Honey ABBA I Do I Do I Do I Do I Do ABBA I Have A Dream ABBA Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me ABBA Mama Mia ABBA Money Money Money ABBA Name Of The Game ABBA One Of Us ABBA Ring Ring ABBA Rock Me ABBA So Long ABBA SOS ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take A Chance On Me ABBA Thank You For The Music ABBA Voulezvous ABBA Waterloo ABBA Winner Takes All Abbott, Gregory Shake You Down Abbott, Russ Atmosphere ABC Be Near Me ABC Look Of Love ABC Poison Arrow ABC When Smokey Sings Abdul, Paula Blowing Kisses In The Wind Abdul, Paula Cold Hearted Abdul, Paula Knocked -

How to Use This Songfinder

as of 3.14.2016 How To Use This Songfinder: We’ve indexed all the songs from 26 volumes of Real Books. Simply find the song title you’d like to play, then cross-reference the numbers in parentheses with the Key. For instance, the song “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive” can be found in both The Real Book Volume III and The Real Vocal Book Volume II. KEY Unless otherwise marked, books are for C instruments. For more product details, please visit www.halleonard.com/realbook. 01. The Real Book – Volume I 10. The Charlie Parker Real Book (The Bird Book)/00240358 C Instruments/00240221 11. The Duke Ellington Real Book/00240235 B Instruments/00240224 Eb Instruments/00240225 12. The Bud Powell Real Book/00240331 BCb Instruments/00240226 13. The Real Christmas Book – 2nd Edition Mini C Instruments/00240292 C Instruments/00240306 Mini B Instruments/00240339 B Instruments/00240345 CD-ROMb C Instruments/00451087 Eb Instruments/00240346 C Instruments with Play-Along Tracks BCb Instruments/00240347 Flash Drive/00110604 14. The Real Rock Book/00240313 02. The Real Book – Volume II 15. The Real Rock Book – Volume II/00240323 C Instruments/00240222 B Instruments/00240227 16. The Real Tab Book – Volume I/00240359 Eb Instruments/00240228 17. The Real Bluegrass Book/00310910 BCb Instruments/00240229 18. The Real Dixieland Book/00240355 Mini C Instruments/00240293 CD-ROM C Instruments/00451088 19. The Real Latin Book/00240348 03. The Real Book – Volume III 20. The Real Worship Book/00240317 C Instruments/00240233 21. The Real Blues Book/00240264 B Instruments/00240284 22. -

SGA Candidates Debate, Revea Platform Issues

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2000s) Student Newspapers 4-19-2004 Current, April 19, 2004 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, April 19, 2004" (2004). Current (2000s). 182. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s/182 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2000s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. April 19, 2004 -... IS$UE . Your source for campus news and information .' 1 :~11 s -:,'. ; __ -4 Eternally yours THECURRENTONLlNE.COM U N\lVERSITY OF MIS SOURI • ST. LOUI S Newgrant SGA candidates debate, Speaker says will fund comprOOllse• counseling revea platform issues is essential BY BECKY R OSNER for patients, NeuJs Editor for peace in Student Government Association families candidates for president and vice president pmticipated in a debate on Middle I~ ast Thursday at 2 p.m. in the SGA The program offers free chambers of the Iv1illennium Student BY WILL MELTON Center, which was hosted by The sem.ces to to those with OUTent. Moderator of the debate, Jason neuromuscular diseases Granger, editor-in-chief of The Students, faculty, staff and Current, started the event out by members of the community were given an opportunity to attend a talk BY EUGENE CLARK stating the basic rules of tbe debate and introducing each of the candidates about the efforts to establish peace in StaffWritm· participating. -

Son.Writers & Publishers

Son.writers & Publishers ARTISTS & MUSIC NO_ 7 SONG CRE TI TL E - W R I T E R - P LI B L I A Short -List Of German Global Hits THE HOT 100 CANDLE IN THE WIND 1997 /SOMETHING ABOUT THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT Elton John, Bernie Taupin Songs Of Polygram Int'I /BMI, William A. Bong/PRS, Warner -Tamerlane /BMI, Wretched /ASCAP, WB /ASCAP Country Continues To Contribute To Int'l Pop HOT TRACKS COUNTRY SINGLES & LONGNECK BOTTLE Steve Wariner, Rick Carnes Steve Wariner /BMI, PSO Limited /ASCAP, BY ELLIE WEINERT group Sash! The group, comprising Freudenthaler and Volker Hinkel of the Songs Of Peer /ASCAP dance producer/writers Thomas'Alis- pop act Fool's Garden, who are signed HOT R &B SINGLES MY BODY Darrell Allamby, Lincoln Browder, Antionette Roberson Tonl Robi /ASCAP, MUNICH -Pop songs with origins in son" Lüdke, Ralf "Kappi" Kappmeier, to EMI Music Publishing, have 2000 Watts /ASCAP Germany have been making successful and DJ Sascha Lappessen, struck it achieved enviable success not only in HOT RAP SINGLES trips abroad. really big with its second single, "En- Europe but in Asia -Pacific markets. IT'S ALL ABOUT THE BENJAMINS /BEEN AROUND THE WORLD S. Jacobs, J. Phillips, D. Styles, Christopher Wallace, K. Jones, Sean "Putty" Combs Doric Angelettie, David Bowie Sheek That current success is a continua- core Une Fois" (One More Time) Their song "Lemon Tree" won "song of Louchfon /ASCAP, Jae'wons /ASCAP Panlro's /ASCAP? Big Poppa/ASCAP, EMI April /ASCAP, tion of the nation's past contributions to (Mighty/Polydor), which has been a hit the year" in the annual airplay awards Undeas/BMI, Crazy Cat Catalog /ASCAP the contemporary pop scene. -

"Object Writing"

Object Writing - Exercise Your Metaphor Muscles One of the basic building blocks of songwriting is, of course, metaphor. A simple object or image can convey the emotion or whole focus or story of a song. For example, here are some songs with objects at the heart of them, most of them big hits. Time in a Bottle – Jim Croce; Message in a Bottle – Sting; Longneck Bottle – Garth Brooks How about a Firework? – by songwriters Esther Dean, Mikkel Eriksen, Sandy Wilhelm and Katy Perry Max Martin, Johan Schuster and Taylor Swift got a whole song out of a Blank Space. Chrome Fish became a song about how some Christians with that emblem stuck on their back bumpers have pretty bad manners behind the wheel. (by Joe Beck and Billy Sprague, two of our faculty writers) Object writing has created hit songs for decades from common things like a bikini, chewing gum and even road kill. Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini - Bryan Hyland 1960 Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavor on the Bedpost Overnight? 1959 by Lonnie Donnegan, later recorded by the Muppets Dead Skunk in the Middle of the Road – Lowden Wainwright III 1972 From a simple ring: This Diamond Ring – Gary and the Playboys; Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It) – Beyonce To a car: Little Duece Coup - Beach Boys; Mercedez Benz – Janis Joplin; Pink Cadillac – Bruce Springsteen; Little Red Corvette – Prince Or a bird: Black bird – the Beatles; Hummingbird – Seals and Croft; Bluebird - Sara Bareilles; Rockin Robin - Bobby Day; Mockingbird – James Taylor; Fly Like an Eagle – Steve Miller Band Take a look and listen to the song Bus Stop by the Hollies. -

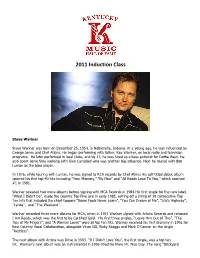

Steve Wariner

2011 Induction Class Steve Wariner Steve Wariner was born on December 25, 1954, in Noblesville, Indiana. At a young age, he was influenced by George Jones and Chet Atkins. He began performing with father, Roy Wariner, on local radio and television programs. He later performed in local clubs, and by 17, he was hired as a bass guitarist for Dottie West. He also spent some time working with Glen Campbell who was another big influence. Next he toured with Bob Luman as the bass player. In 1976, while touring with Luman, he was signed to RCA records by Chet Atkins His self-titled debut album spurred his first top 40 hits including “Your Memory,” “By Now” and “All Roads Lead To You,” which reached #1 in 1981. Wariner released two more albums before signing with MCA Records in 1984.His first single for the new label, “What I Didn’t Do”, made the country Top Five and in early 1985, setting off a string of 18 consecutive Top Ten hits that included the chart-toppers “Some Fools Never Learn”, “You Can Dream of Me”, “Life’s Highway”, “Lynda”, and “The Weekend”. Wariner recorded three more albums for MCA, when in 1991 Wariner signed with Artista Records and released I Am Ready, which was the first to be Certified Gold. His first three singles, “Leave Him Out of This”, “The Tips of My Fingers”, and “A Woman Loves” were all top ten hits. Wariner received his first Grammy in 1992 for Best Country Vocal Collaboration, alongside Vince Gill, Ricky Skaggs and Mark O’Connor on the single “Restless”.