Study Protocol to Investigate the Effect of a Lifestyle Intervention on Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Sheffield

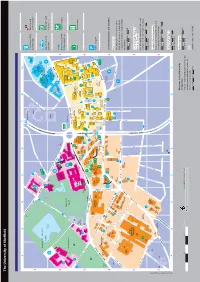

Index The University of Sheffield 95 Map Number Faculty Offices Parking Services G1 190 Grid Reference > Arts and Humanities F3 184 Perak Laboratories D2 110 > Engineering H2 170 Philippa Cottam Communication Clinic B4 51 95 > Medicine, Dentistry and Health B5 88 Philosophy F3 161 95 > Science E2 117 Physics and Astronomy E3 121 ABCDEF GH > Social Sciences G3 197 Planning and Governance Services F4 174 Finance Department D2 104 Politics A2 31 95 95 95 Firth Court D3 105 Polymer Centre (Research) E2 117 Netherthorpe 95 Firth Hall D3 105 Portering Services D2 104 Academic Unit of Clinical Oncology A4 41 University parking Bus stop and Florey Building D3 114 Portobello Centre H3 177 193 Academic Unit of Medical Education D5 141 French F3 184 Postgraduate Student Enquiries D3 120 101 Accommodation and Commercial Services 10 Opal 2 (permit only) service number Print and Design Solutions D2 151 Activities and Sports Zone D3 120 192 95 95 Probability and Statistics E3 121 Bartolomé Addison Building D3 113 House Kroto enomic Medicine B5 87 Procurement and Supplies D2 104 Admissions Section D2 104 G Research Geography D2 102 PropertywithUS D3 120 10 Adult Dental Care B4 47 Institute George Porter Building G1 190 Psychology B3 34 95 190 Aerospace Engineering H2 170 Germanic Studies F3 184 Pure Mathematics E3 121 George Porter North 95 Alfred Denny Building D3 111 Goodwin Sports Centre A2 30 Building Campus 95 Alumni Relations E4 147 Graduate Research Centre Sheffield International Supertram stop Banks with cash Amy Johnson Building H3 173 Boating -

Annual Report & Accounts 2011/12

Annual Report & Accounts 2011/12 Barnsley Hospital NHS FT Annual Report 2011/12 1 Barnsley Hospital NHS FT Annual Report 2011/12 2 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Schedule 7, paragraph 25(4) of the National Health Service Act 2006. Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Annual Report and Accounts 2011/12 Barnsley Hospital NHS FT Annual Report 2011/12 3 Barnsley Hospital NHS FT Annual Report 2011/12 4 Contents About Barnsley Hospital Directors’ Report & Business Review Page 7 - Chairman and Chief Executive overview - Board of Directors - Management team - Performance overview - Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) - Providing high quality and safe services - Designing healthcare around the needs of our patients - Investing in our workforce - Making the best use of resources - Financial review Quality - Quality Report Page 58 Governance - Corporate governance Page 120 Governing Council Board of directors Committees Remuneration report Relations with members - Other disclosures Statement of accounting officer’s responsibilities Page 154 Annual Governance Statement Page 155 Financial Statements Page 167 Barnsley Hospital NHS FT Annual Report 2011/12 5 About Barnsley Hospital Barnsley Hospital NHS Foundation Trust was founded on 1 January 2005 under the Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act 2003, as re-enacted in the National Health Service Act 2006 (the 2006 Act). We were one of the first hospitals in the country to become a Foundation Trust. Since becoming a Foundation Trust in 2005 Barnsley Hospitals NHS Foundation trust has sought to utilise the foundation trust regime that this brings to benefit our patients. We provide a range of acute hospital services. These include emergency and intensive care, medical and surgical services, elderly care, paediatric and maternity services and diagnostic and clinical support services. -

How to Find Us

Reaching us by car Public Transport From the M1 - Exit the motorway at J34 Car parking around the hospital is limited so public (Meadowhall) and follow signs for Sheffield City transport is often the easiest way to get to us. The Centre (A6109). Continue on the A6109 past hospital is well served by public transport, with several Meadowhall to the Brightside roundabout. bus stops within easy reach. How to Take the third exit, signposted Hillsborough Up to date information about public transport links (A6102). Continue to follow the A6102, go and Park & Ride sites is available from Travel South straight across at the Fir Vale traffic lights then Yorkshire. find us after about half a mile turn right into the hospital Travel Line tel: 01709 51 51 51 grounds (Herries Road entrance). www.travelsouthyorkshire.com From the City Centre - Follow Barnsley Road The Northern (A6135) to Fir Vale. Help with your travel expenses To reach the Barnsley Road entrance go If you are entitled to certain low income support General Hospital straight on at the Fir Vale traffic lights. The benefits you may be able to receive help with your Herries Road, Sheffield hospital entrance is the first turning on the left. train, car mileage and bus fares to and from hospital. To reach the Herries Road entrance turn left at Further information and advice is also available from Satnav S5 7AT the Fir Vale traffic lights onto Herries Road. the hospital cashiers on 0114 271 4927. Tel: 0114 243 4343 The entrance is about half a mile on the right. -

How to Find Us

Reaching us by car Public Transport From the M1 - Exit the motorway at Car parking around the central hospitals J33 and follow the A630 and A57 into is extremely limited so public transport How to Sheffield. is often the easiest way to get to us. At the Park Square roundabout take All our hospitals are well served the A61(S), passing the railway station by public transport, with several bus on your left. find us stops within easy reach. Follow signs for the ringroad (A61 Supertram can be used to reach the Barnsley), you will soon start to see Royal Hallamshire, Jessop Wing, Charles signs to the hospitals. Clifford and Weston Park Hospitals, Central Campus although there is a 10 - 15 minute uphill From the A61 South - Follow the A61 walk from the nearest stop (University). into the city. Just after the Halfords This leaflet covers: Up to date information about public superstore, turn left on Bramall Lane transport links and Park & Ride sites is • The Royal Hallamshire Hospital (A621), passing the football stadium on available from Travel South Yorkshire. your right. • Charles Clifford Dental Hospital Travel Line tel: 01709 51 51 51 At the roundabout take the first exit • Weston Park Hospital and follow the A61 Barnsley. You will www.travelsouthyorkshire.com • Jessop Wing Maternity Hospital soon start to see signs to the hospitals. The Royal Hallamshire Hospital Glossop Road, Sheffield S10 2JF Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS A separate map is available for the Tel 0114 271 1900 Foundation Trust runs five adult Northern General Hospital. You can The Jessop Wing hospitals as well as services in find the map on our website Tree Root Walk Sheffield S10 2SF A shuttle bus usually runs the community: www.sth.nhs.uk. -

NGH Map Sept 2016.Pdf

Reaching us by car Public Transport From the M1 - Exit the motorway at J34 Car parking around the hospital is limited so public (Meadowhall) and follow signs for Sheffield City transport is often the easiest way to get to us. The Centre (A6109). Continue on the A6109 past hospital is well served by public transport, with several Meadowhall to the Brightside roundabout. bus stops within easy reach. How to Take the third exit, signposted Hillsborough Up to date information about public transport links (A6102). Continue to follow the A6102, go and Park & Ride sites is available from Travel South straight across at the Fir Vale traffic lights then Yorkshire. find us after about half a mile turn right into the hospital Travel Line tel: 01709 51 51 51 grounds (Herries Road entrance). www.travelsouthyorkshire.com From the City Centre - Follow Barnsley Road The Northern (A6135) to Fir Vale. Help with your fares To reach the Barnsley Road entrance go If you are entitled to certain social security benefits you General Hospital straight on at the Fir Vale traffic lights. The may be able to get help with your train or bus fares to Herries Road, Sheffield - Satnav S5 7AT hospital entrance is the first turning on the left. the hospital. To do this you should contact your local To reach the Herries Road entrance turn left at Social Security office. Tel: 0114 243 4343 the Fir Vale traffic lights onto Herries Road. Further information and advice is also available from www.sth.nhs.uk The entrance is about half a mile on the right. -

An Evaluation of the Impact of Weston Park Cancer Support Centre

An Evaluation of the Impact of Weston Park Cancer Support Centre Author(s): Chris Dayson Jan Gilbertson David Leather January 2020 DOI: 10.7190/cresr.2019.3247799239 Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to all the staff at the Weston Park Cancer Support Centre who supported the evaluation. We would like to thank Sarah Saunby who advised on available CSC data and helped us with our data scoping and assessment. Special thanks also go to Isabel Hartland for her help with data sharing and contract agreements and to Hannah Hall and Emma Clarke for skilfully taking up liaison for the project part way through the evaluation. Contents Headline Summary ........................................................................................................................ i 1. Introduction and context ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Background to the evaluation ........................................................................................... 1 1.3. Context ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.4. Services at Weston Park CSC .......................................................................................... 2 1.5. Volunteers ....................................................................................................................... -

A Pilot Study Examining Nutrition and Cancer Patients: Factors Influencing Oncology Patients Receiving Nutrition in an Acute Cancer Unit

A pilot study examining nutrition and cancer patients: factors influencing oncology patients receiving nutrition in an acute cancer unit. WARNOCK, C., TOD, A., KIRSHBAUM, M., POWELL, C. and SHARMAN, D. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/287/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version WARNOCK, C., TOD, A., KIRSHBAUM, M., POWELL, C. and SHARMAN, D. (2006). A pilot study examining nutrition and cancer patients: factors influencing oncology patients receiving nutrition in an acute cancer unit. Clinical effectiveness in nursing., 9 (3/4), 197-201. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk A pilot study examining nutrition and cancer patients: factors influencing oncology patients receiving nutrition in an acute cancer unit Authors Clare Warnock MSc, BSc, RN Practice Development Sister, Weston Park Hospital, Directorate of Cancer services, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Witham Road, Sheffield, England, S10 2SJ Angela Tod PhD, MSc, MMedSci, RN Sheffield Hallam University Marilyn Kirshbaum PhD, MSc, BSc, RN (New York), RGN (UK), DipOnc Sheffield Hallam University Claire Powell, RN Dermatology nurse specialist, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Denise Sharman, RN Clinical risk nurse, Directorate of gynaecology and urology, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Correspondence to: Clare Warnock, Practice Development Sister. 4 th floor, Weston park Hospital, Witham Road Sheffield S10 2SJ Email: [email protected] Phone: 0114 226 5311 Key words: Nutrition, Cancer, Observation A pilot study examining nutrition and cancer patients: factors influencing oncology patients receiving nutrition in an acute cancer unit Introduction There is national concern in the UK regarding the poor nutritional status of patients in hospital (NICE 2006, Department of Health 1999). -

Passport Activity Newsletter

Passport Activity Newsletter Spring 2020 Welcome to the Spring edition of our Sheffield CU Passport Activity Newsletter. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, many of our Learning Destinations are not running activities as normal, which means this newsletter is much smaller than usual. But fear not, we’ve still included some of their activities and others may still be delivering activities online or via Zoom etc. CU credits can be earned by taking part in these and Learning Destinations will be sending us registers as usual. Others may be producing online, downloadable activities so keep an eye on their websites and social media for more info. We’re also continuing with our 2020: Year of the Nurse and Midwife activities and they’re all included in this newsletter, so there’s plenty to choose from. We’ve now published out 50th daily CU Home Learning Challenge since schools closed to most pupils, and we’re LOVING seeing your photos, videos and examples of the fantastic learning you’ve been choosing to do at home! Do keep sharing them with us. There is information on each of the challenges which explains how you can claim CU credits for completing these challenges if you normally attend a Sheffield school and have a Passport to Learning. If you see challenges published by other CUs, then do feel free to complete them. To claim your CU credits, you’ll need to download a diary sheet from our website (or use the one attached to the back of this newsletter!) and email it in to us to make sure your credits are counted! Find Learning Destinations in Sheffield (www.sheffield.gov.uk/cu) and beyond at www.childrensuniversity.co.uk If you would like to join our Parent/Carer Mailing list to receive updates, activity information and news, please email [email protected] . -

Annual Report 2012 Single Page

Annual Report 2011/2012 Board and Staff Founder and Life President David Simons Vice Presidents Roy Finch Lady Neill Professor Malcolm Reed Trustees John Bryan Roy Finch Julietta Patnick Sue Shepley Dr June Smailes Nick Stratford Peter Crossland Sharon Kay Karen Codling Fundraising Team Kate Senter Annie Sutherland Management Team Jonny Cole Jess Osborn Sally Eustace Head of Finance & Resources Lynn Seymour Patrons Head of Therapy Services Kerrie Gosney Suzanne Liversidge Reception and Administration Jackie Drayton Team Harry Gration Jennifer Dickinson (Retired Sept 11) Councillor Mike Pye Dallas McDade Chris Waddle Jane Beatson Claire Stacey-Midgley Glynis Sullivan Rotherham Cancer Care Angela Bintcliffe Services Co-ordinator Chairman's Report This is my first year as Chairman of the Board of Trustees, and it has certainly been what I think is called a ‘learning experience’. But I am pleased to report that we end the year with our finances in good shape, our reputation strong, and our vital work continuing to make a huge difference in the lives of many people in our community. Although this report refers to our year ending April 2012, I think it would be wrong of me not to mention two important issues that are in all our minds at present. The shock of two of our key staff falling seriously ill still resonates, and our best wishes for their best possible recoveries go out to Jess and Lynn. Secondly, the economic climate means we must also address a step change in our longer term funding. But these challenges only serve to underline the fantastic spirit that surrounds and underpins the Cavendish, and that makes us such a valuable charity in the cancer world. -

The Patient's Handbook

The Patient’s Handbook All you need to know about being a St Luke’s patient Adding quality to life 1 How to use this publication You need read only the pages which interest you at the moment, but please keep this book handy so that you can refer to it if you use other parts of our service in the future. The white pages contain general information about the Hospice, the way it works, and the type and level of care you can expect from us. The green pages contain information you need if you are a day patient. The blue pages contain information you need if you are an in-patient. The yellow pages contain information you need if you live at home and our community specialist palliative care nursing team is involved in your care. At the back of each coloured section you’ll find some lined pages. You, or members of our staff, can use these to note anything you need to know or remember. Your name 2 3 Contents Welcome to St Luke’s Hospice 4 – What is St Luke’s? 4 – Who our patients are 5 – Caring for individual needs 5 – What we can provide for you 6 – How you become a patient 7 – Your medical and nursing care 7 – Our professional advisers and therapists 8 – How we are funded – and how we raise funds 8 – Will we charge for your care? 9 – Having your say 9 St Luke’s in the Sheffield community 11 – Bereavement service 11 – Education department 12 – Volunteers 13 – Working within a city-wide team 14 How to get to us – Route map 17 – Ground plan of the site 18 Caring for you at our therapies and rehabilitation centre Green pages 21–43 Caring for you as an in-patient Blue pages 45–79 Caring for you at home Yellow pages 81–91 Working to high standards 93 Policies which affect you 94 Index 96 4 5 Welcome to St Luke’s Hospice Who our patients are Most people associate us with caring for people with advanced What is St Luke’s? cancer, but we also care for those with non-cancer conditions. -

Streamlining the Search for Stem Cells

BSBMT NEWS British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation Issue Number 10 - December 2011 INSIDE... STREAMLINING “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty THE SEARCH FOR pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.” (Mr Micawber, David Copperfield) STEM CELLS 2012 will bring the bicentenary of the birth of Charles Dickens, a man who Peter Zarko-Flynn, Ann Green and Bronwen Shaw knew something about debt. Thanks to a perfect storm of financial fecklessness, dishonesty and incompetence, we anticipate frugal times ahead. Graham Jackson sets out some of the resulting challenges to transplant practice and calls for the active involvement of the BSBMT membership in maintaining and developing good practice in the service of our patients. Peter Zarko-Flynn and Ulrike Paulus describe developments in our sister organisations, the Anthony Nolan and the NHSBT while John Snowden and colleagues highlight the effective workings of the Sheffield transplant centre. Elsewhere, challenges in clinical practice are addressed by Ruth Ashbee and Chris Fox. The future of transplantation depends not only on funding, but on talent: Coming through the ranks are Venetia Bigley and Clare Bennett, both winners at the annual BSBMT Scientific meeting as In December 2010 the Department of Health published a report by the UK well as Chris Parrish who provides our Stem Cell Strategic Forum, which was led by NHS Blood and Transplant journal club selection. Life is not all about (NHSBT). The report set out recommendations to save over 200 lives a work - congratulate Venetia on her new baby and also note that The Harvard year by increasing the availability of stem cells for patient transplantation. -

Agenda Item 7

Agenda Item 7 PLANNING AND HIGHWAYS COMMITTEE 11 th July 2017 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION APPLICATIONS UNDER VARIOUS ACTS / REGULATIONS – SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1. Application Number 17/00712/FUL Address University of Sheffield Sports Pitches, Goodwin Athletics Centre, Northumberland Road/Whitham Road Amended Conditions Condition 4 Following the submission of an amended Phase 1 and Phase II Contaminated Land Risk Assessment, condition 4 can be amended as follows: 4. A Phase II risk assessment in respect of asbestos identified under report ref: FSS-MMD-00-XX-RP-C-0003/C, Revision C, dated July 2017 (Mott MacDonald) shall be undertaken. The report shall have been submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority prior to the development commencing. The Report(s) shall be prepared in accordance with Contaminated Land Report CLR 11 (Environment Agency 2004). Reason: In order to ensure that any contamination of the land is properly dealt with. Condition 8 The development involves moving bus stop locations closer to the pedestrian crossing outside the Weston Park Hospital and there is a highway safety concern that the existing signal-heads might be obscured by waiting buses. As such condition 8 included the requirement to provide cantilevered back-to-back signal- heads over the carriageway. After concerns expressed by the applicant about the necessity for this provision, Condition 8 has been amended such that providing the cantilevered signal heads will only be necessary if determined by an independent Road Safety Audit. 8. No development shall commence until the improvements (which expression shall include traffic control, pedestrian and cycle safety measures) to the highways listed below have either; a) been carried out; or b) details have been submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority of arrangements which have been entered into which will Page 1 secure that such improvement works will be carried out before the development is brought into use.