If We Are Honest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010-2011 Kidd Core Texts for Fiction Sections

20102011 Kidd Core Texts For Fiction Sections Fiction—26 stories Isaac Babel: “Crossing into Poland” Richard Bausch: “What Feels Like the World” Raymond Carver: “Popular Mechanics” Lan Samantha Chang “Eve of the Spirit Festival” Anton Chekhov: “The Bishop” & “On Technique in Writing a Short Story” Andre Dubus: “A Father’s Story” Susan Glaspell: “A Jury of Her Peers” Ryan Harty: “Why the Sky Turns Red When the Sun Goes Down” Adam Haslett: “Devotion” James Joyce: “The Dead” Alice Munro: ““Prue” and “What Is Real?” Antonya Nelson: “Stitches Teá Obrecht: “The Laugh” Tim O’Brien: “The Things They Carried” and “Telling Tails” (craft) Flannery O’Connor: “A Good Man is Hard to Find” & “Writing Short Stories” Julia Orringer: “Pilgrims” Daniel Orzoco “Orientation” Benjamin Percy: “Refresh Refresh” and “Home Improvement” Adam Prince: “A. Roolette? A. Roolette?” Mark Richard: “Strays” Norman Rush: “Near Pala” Karen Russell: “Vampires in the Lemon Grove” Elizabeth Strout: “Incoming Tide” Alice Walker: “Roselily” Eudora Welty: “Where is the Voice Coming From?” and Doris Betts: “Killers Real & Imagined” (Welty’s response to the murder of Medgar Evers) Tobias Wolff: “Powder” Visiting Fiction Writers Kent Meyers: “Easter Dresses” and “Wind Rower” (fall) Jon Raymond: “Train Choir” (winter) Suggested: the film Wendy & Lucy based on “Train Choir” Margot Livesey: “The Niece” (spring) Fiction Faculty Ehud Havazelet: “Pillar of Fire” and “Writing Pillar of Fire” (fiction and essay) David Bradley: “The Faith” (both essay and craft) and “…By Any Other Name” (eulogy/opinion) Laurie Lynn Drummond: “Something About a Scar” (fiction) and “Girl, Fighting” (creative nonfiction) 2010-2011 Kidd Core Readings—2 Fiction—14 craft essays Francine Prose: “Close Reading” David Jauss: “Autobiographobia: Writing and the Secret Life” John Gardner: “Aesthetic Law & Artistic Mystery” & “Basic Skills, Genre, and Fiction as Dream” (I suggest you teach these together) John Barth: “Incremental Perturbations” C. -

CITY LIGHTS PUBLISHERS CELEBRATING 60 YEARS 1955-2015 261 Columbus Ave | San Francisco, CA 94133

CITY LIGHTS PUBLISHERS CELEBRATING 60 YEARS 1955-2015 261 Columbus Ave | San Francisco, CA 94133 Juan Felipe Herrera has been appointed the 21st Poet Laureate of the United States for 2015-2016! Forthcoming from City Lights this September will be Herrera’s new collection of poems titled Notes on the Assemblage. Herrera, who succeeds Charles Wright as Poet Laureate, said of the appointment, “This is a mega-honor for me, for my family and my parents who came up north before and after the Mexican Revolution of 1910—the honor is bigger than me. I want to take everything I have in me, weave it, merge it with the beauty that is in the Library of Congress, all the resources, the guidance of the staff and departments, and launch it with the heart-shaped dreams of the people. It is a miracle of many of us coming together.” Herrera joins a long line of distinguished poets who have served in the position, including Natasha Trethewey, Philip Levine, W. S. Merwin, Kay Ryan, Charles Simic, Donald Hall, Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Billy Collins, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Pinsky, Robert Hass and Rita Dove. The new Poet Laureate is the author of 28 books of poetry, novels for young adults and collections for children, most recently Portraits of Hispanic American Heroes (2014), a picture book showcasing inspirational Hispanic and Latino Americans. His most recent book of poems is Senegal Taxi (2013). A new book of poems from Juan Felipe Herrera titled Notes on the Assemblage is forthcoming from City Lights Publishers in September 2015. -

A a a from the Americans 3. Help, 1968 After a Photograph from The

from The Americans 3. Help, 1968 After a photograph from The Americans by Robert Frank When I see Frank’s photograph of a white infant in the dark arms of a woman who must be the maid, I think of my mother and the year we spent alone—my father at sea. The woman stands in profile, back against a wall, holding her charge, their faces side-by-side—the look on the child’s face strangely prescient, a small dimple furrowing the space between her brows. Neither of them looks toward the camera; nor do they look at each other. That year, when my mother took me for walks, she was mistaken again and again for my maid. Years later she told me she’d say I was her daughter, and each time strangers would stare in disbelief, then empty the change from their pockets. Now I think of the betrayals of flesh, how she must have tried to make of her face an inscrutable mask and hold it there as they made their small offerings— pressing coins into my hands. How like the woman in the photograph she must have seemed, carrying me each day—white in her arms—as if she were a prop: a black backdrop, the dark foil in this American story. Natasha Trethewey1 1“The Americans” by Natasha Trethewey from Thrall, Mariner Books. Used by permission. Reflections I’m thrilled that Natasha Trethewey has agreed to come to Richmond, Virginia, to read from her work. In anticipation of her visit, I have prepared the next two editions of Wellspring to highlight a poem from her most recent collection, Thrall. -

A New Selected Poetry Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Behind My Eyes

Poetry.A selection of poetry titles from the library’s collection, in celebration of National Poetry Month in April. ** indicates that the author is a United States Poet Laureate. A New Selected Poetry ** The Collected Poems of ** The Complete Poems, Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Robert Lowell 1927-1979 Robert Lowell; edited by Frank Elizabeth Bishop • 811.54 BI Behind My Eyes Bidart and David Gewanter • Li-Young Lee • 811.54 LE 811.52 LO The Complete Poems William Blake • 821 BL ** The Best Of It: New and ** The Collected Poems of Selected Poems William Carlos Williams The Complete Poems Kay Ryan • 811.54 RY Edited by A. Walton Litz and Walt Whitman • 811 WH Christopher MacGowan • The Best of Ogden Nash 811 WI The Complete Poems of Edited by Linell Nash Smith • Emily Dickinson 811.52 NA The Complete Collected Poems Edited by Thomas H. Johnson • of Maya Angelou 811.54 DI The Collected Poems of Maya Angelou • 811.54 AN Langston Hughes The Complete Poems of Arnold Rampersad, editor; David Complete Poems, 1904-1962 John Keats Roessel, associate editor • E.E. Cummings; edited by John Keats • 821.7 KE 811.52 HU George J. Firmage • 811.52 CU E.E. Cummings Elizabeth Bishop William Blake Emily Dickinson Ocean City Free Public Library 1735 Simpson Avenue • Ocean City, NJ • 08226 609-399-2434 • www.oceancitylibrary.org Natasha Trethewey Pablo Neruda Robert Frost W.B. Yeats Louise Glück The Essential Haiku: Versions of Plath: Poems ** Selected Poems Basho, Buson, and Issa Sylvia Plath, selected by Diane Mark Strand • 811.54 ST Edited and with verse translations Wood by Robert Hass • 895.6 HA Middlebrook • 811.54 PL Selected Poems James Tate • 811.54 TA The Essential Rumi The Poetry of Pablo Neruda Translated by Coleman Barks, Edited and with an introduction Selected Poems with John Moyne, A.A. -

The Southern Review: Hoops Reviewed by David Wojahn

The Southern Review History Shaping Selves: Four Poets by David Wojahn Native Guard: Poems by Natasha Trethewey (Houghton Mifflin Company) Hoops: Poems by Major Jackson (W. W. Norton & Company) Sugartown by David Rivard (Graywolf Press) Salvation Blues: One Hundred Poems, 1985‐2005 by Rodney Jones (Houghton Mifflin Company) Full Text :COPYRIGHT 2007 Louisiana State University IN THE TITLE POEM of his late‐in‐life collection, History, Robert Lowell writes that "History has to live with what was here‐‐/clutching and close to fumbling all we had." This famously visceral poet refuses to make history an abstraction; it is an august but gangling force, a kind of murky, debris‐ and detritus‐laden river, flowing relentlessly, and in its currents the public and the personal are impossible to distinguish from one another. As Lowell insists in many of his greatest poems‐‐think of the embittered elegy for Colonel Shaw and his black regiment in "For the Union Dead"‐‐selves write history, but history shapes selves in powerfully mysterious ways. This is certainly not a fashionable contention, but I think it is one shared by all of the four poets under discussion here. They are not by any means Lowell's descendants, but they share with him a desire to superimpose the historical upon the personal; and for them the river of history is even more turbid than it was for the aristocratic Lowell, involving above all matters of race and of class, currents which Lowell with his patrician sense of entitlement could not have so acutely identified. Natasha Trethewey and Major Jackson are young African American poets concerned not so much with problems of identity politics as with the challenge of forging an authentic and personal voice in an era when definitions of African American literary identity promise to be significantly reconfigured. -

Daniel Tobin from This Broken Symmetry (Simone Weil, 1943-1909)

Daniel Tobin from This Broken Symmetry (Simone Weil, 1943-1909) (Rio Ebro) After turning away from the rearguard of Paris, the safe House of her pacifism, with her parents following, afraid She will do something silly, after descending with the militia Through Lerida into Aragon to the banks of the Ebro To take up her rifle there, her comrades at target practice Fleeing anywhere near her line of fire (Lord deliver us From mousey women); after crossing to the other side Where Phalangists wait in this war without prisoners “For if one is captured, one is dead,” she hugs ground Only to look up, stretched out on her back as the spitfire Flies past on reconnaissance, thinking she will be caught, And sees nothing other than the increase of blue sky, This “infinity of perfect beauties, of all things that were Or will be,” and looks for an instant “beyond the veil To the real presence,” objectless, adoring the distance (Though “all the horrors of this world are like the folds Imposed on waves by gravity”) between God and God, Until the stooping man one thinks one sees on the road At dusk reveals a tree, and the voices heard just leaves Rustling on Los Picos des Tres Maras where the river begins — Before the bivouacs resume and she burns herself with oil, Before her comrades who will fight and die carry her out, Before her parents who did not expect to see her again See her again, arrived safely, smiling, radiant: “Here I am.” 96 Alabama Literary Review Brand Brightly vested in their loose smocks, the ebullient troop sways rhythmically onto the floor, their gold drums strapped before them around their waists. -

Notable Contributors to the North American Review

Notable Contributors to the North American Review AMERICAN WRITERS Stephen Dunn* Conrad Aiken* Washington Irving Margaret Atwood Joseph Auslander William Cullen Bryant Bobbie Ann Mason Robert Penn Warren* Ralph Waldo Emerson Maxine Hong Kingston Karl Shapiro* Henry Wadsworth Longfellow John Edgar Wideman William Stafford John Greenleaf Whittier Stuart Dybek Mona Van Duyn* Harriet Beecher Stowe James Tate* James Dickey James Russell Lowell Barry Lopez Philip Levine* Walt Whitman Annie Dillard* Mark Strand* Rebecca Harding Davis Scott Russell Sanders Charles Wright* Horatio Alger Yusef Komunyakaa* Ted Kooser Mark Twain Albert Goldbarth Billy Collins William Dean Howells T.C. Boyle Rita Dove* Henry James* Alberto Ríos Natasha Trethewey* Joel Chandler Harris Tony Hoagland Charlotte Perkins Gilman Louise Erdrich U.S. PRESIDENTS Hamlin Garland* Dean Young John Adams Edith Wharton* Ha Jin Thomas Jefferson Edith Hamilton Martín Espada Abraham Lincoln Mary Austin Madison Smart Bell Ulysses S. Grant Booth Tarkington* Diana Abu-Jaber James A. Garfield George Sterling Bob Hicok Benjamin Harrison Edwin Arlington Robinson* Antonya Nelson Grover Cleveland Theodore Dreiser Ray Gonzalez William McKinley Amy Lowell* Jennifer Egan* Woodrow Wilson Upton Sinclair* Steve Almond William H. Taft Sara Teasdale* C. Dale Young Theodore Roosevelt Margaret Widdemer* Aimee Bender Franklin D. Roosevelt Ezra Pound John Gould Fletcher* NOTABLE AMERICANS INTERNATIONAL Frank Luther Mott* William Ellery Channing CONTRIBUTORS Robert P. T. Coffin* Daniel Webster Victor Hugo -

Kidd 2010-2011: Core Texts for Poetry Sections

Kidd 20102011: Core Texts for Poetry Sections Revisiting as a Writer Ovid: from Metamorphoses, Book IV: “Arachne” and “Niobe” from Beowulf: “The Last Survivor’s Speech” John Donne: “The Flea” Percy Bysshe Shelley: “Ozymandias” Samuel Taylor Coleridge: “Frost at Midnight” Walt Whitman: “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” Emily Dickinson: “There’s a certain Slant of light,” “After great pain, a formal feeling comes—,” “Much Madness is divinest Sense—,” “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant,” “My life closed twice before its close;” and “Fame is a bee” Gerard Manley Hopkins: “Pied Beauty” T.S. Eliot: “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” Robert Frost: any 2 Frost poems, your choice, + 2 of the poems mentioned in Logan or Jarrell essays Poetic Sequence Gjertrud Schnackenberg: Laughing with One Eye: “1. to 12.” Derek Walcott: The Schooner Flight: “1. Adios, Carenage” to “11. After the Storm” Two to three diverse poetry collections: tutor selected Lineation and Stanzation: tutor selected Verse and Meter: Syllabics, Accentuals, AccentualSyllabics Syllabics: any 3 of the following, at least one pattern and one consistent number: Marianne Moore: “The Paper Nautilus” (pattern) or “The Fish” (pattern) Thom Gunn: “My Sad Captains” (7’s, also an elegy) or “Flying Above California” (9’s) Dylan Thomas: “Fern Hill” (pattern) Philip Levine: “Animals Are Passing from Our Lives” (7’s, also a dramatic monologue) Accentuals, Accentual‐Syllabics, [Blank Verse]: tutor selected Forms: Villanelle, Sestina, Sonnet Villanelle: Dylan Thomas: “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” Elizabeth Bishop: “One Art” Wendy Cope: “Reading Scheme” Richard Hugo: “The Freaks at Spurgin Road Field” Sestina: Elizabeth Bishop: “A Miracle for Breakfast” and “Sestina” Anthony Hecht: “The Book of Yolek” 2 Sonnet: William Shakespeare: Sonnet 147 Sir Philip Sidney: from Astrophil and Stella, Sonnet 54 Elizabeth Barrett Browning: from Sonnets from the Portuguese, XVIII W.B. -

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller 04.18.18 Peer-Reviewed By: Jason Camlot & Anon. Clusters: Sound Article DOI: 10.22148/16.022 Dataverse DOI: 10.7910/DVN/FGNBHX Journal ISSN: 2371-4549 Cite: Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller, “Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets,”Cultural Analytics April 18, 2018. DOI: 10.22148/16.022. Literary readings provoke strong feelings, which feed intense critical de- bates.1And while recorded literary readings have long been available for study, 1This research was supported by a 2015-16 ACLS Digital Innovations Fellowship at the Univer- sity of California, Davis, and a grant from the Research Council of the University at California State University, Bakersfield in 2017, and it continues in 2018 with a NEH Digital Humanities Advance- ment grant (see http://textinperformance.soc.northwestern.edu/). Thanks to Hideki Kawahara for generously sharing TANDEM-STRAIGHT, to Dan Ellis for helping us set up his pitch-tracking al- gorithm in Matlab, to Robert Ochshorn and Max Hawkins for their development of the invaluable tools of Gentle and Drift that allowed much of the initial research to be undertaken, to the ModLab and the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of California, Davis, and to undergraduate research assistants Pavel Kuzkin and Richard Kim at UC Davis and Mateo Lara and David Stanley at CSU Bakersfield. Thanks also to Steve McLaughlin, Steve Evans, Christopher Grobe, and Mark Liberman for useful advice, and to the helpful audiences in Stanford’s Material Imagination: Sound, Space and Human Consciousness workshop series and at Cultural Analytics 2017 at the University of Notre Dame, where some of this research was presented. -

Aesthetic Activisms: Language Politics and Inheritances in Recent Poetry from the U.S. South

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2020 Aesthetic Activisms: Language Politics and Inheritances in Recent Poetry From the U.S. South Sunshine Dempsey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dempsey, S.(2020). Aesthetic Activisms: Language Politics and Inheritances in Recent Poetry From the U.S. South. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/6041 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aesthetic Activisms: Language Politics and Inheritances in Recent Poetry from the U.S. South by Sunshine Dempsey Bachelor of Arts Colorado State University, 2006 Master of Fine Arts Colorado State University, 2010 Master of Arts Lynchburg College, 2014 _____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2020 Accepted by: Brian Glavey, Major Professor Michael Dowdy, Committee Member Ed Madden, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Rebecca Janzen, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Sunshine Dempsey, 2020 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION For my grandparents, Robert and Rees Hemphill, and for T and P iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of my committee, Brian Glavey, Michael Dowdy, Tara Powell, Ed Madden, and Rebecca Janzen. Thank you all for your time and your incredibly helpful feedback. -

Eng 2333.001 (12508): W 5:30-8:15, Mh 3.03.06

ENG 2333.001 (12508): W 5:30-8:15, MH 3.03.06 ENG 2333.001 Creative Writing: Poetry Syllabus – Fall 2012 Instructor: Elaine Wong Email: [email protected] Office Location: MB 2.306E Office Phone: 458-7884 Office Hours: M 4:45-5:45, W 4:00-5:00, and by appointment Required Texts 1. Ted Kooser, The Poetry Home Repair Manual: Practical Advice for Beginning Poets, Bison Books, 2007, [0803259786]. (“Manual” on Course Outline.) 2. Billy Collins, Horoscopes for the Dead: Poems, Random House, 2011, [9780812975628]. 3. Jane Hirshfield, Come, Thief: Poems, Alfred A. Knopf, 2011, [9780307595423]. 4. Natasha Trethewey, Native Guard: Poems, Houghton Mifflin, 2006, [9780618872657]. 5. Poems and articles to be downloaded via Blackboard. Course Description This course introduces the craft of poetry writing to students with or without previous poetry- writing experience. The course provides ample opportunities for writing poems, to be guided by weekly readings and themes/genres as assigned by the instructor, as well as for revising and sharing poems through constructive comments from the instructor and class participants. We will pay special attention to how we interact with language as we write poems and how we reach out through poetry writing to other people and beings. Learning Objectives This course facilitates students to 1. develop skills and competence in poetry writing and revision; 2. obtain a sound understanding of elements and terminology of poetry; 3. apply the elements and terminology in poetry writing and reading; and 4. acquire skills in poetry editing and critiquing. UTSA Academic Honor Code A. Preamble The University of Texas at San Antonio community of past, present and future students, faculty, staff, and administrators share a commitment to integrity and the ethical pursuit of knowledge. -

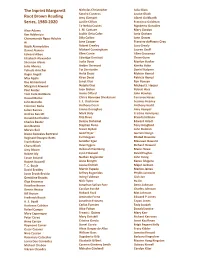

The Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, 1980-2020

The Inprint Margarett Nicholas Christopher Julia Glass Sandra Cisneros Louise Glück Root Brown Reading Amy Clampitt Albert Goldbarth Series, 1980-2020 Lucille Clifton Francisco Goldman Ta-Nehisi Coates Rigoberto González Alice Adams J. M. Coetzee Mary Gordon Kim Addonizio Judith Ortiz Cofer Jorie Graham Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Billy Collins John Graves Ai Jane Cooper Francine duPlessix Gray Rabih Alameddine Robert Creeley Lucy Grealy Daniel Alarcón Michael Cunningham Lauren Groff Edward Albee Ellen Currie Allen Grossman Elizabeth Alexander Edwidge Danticat Thom Gunn Sherman Alexie Lydia Davis Marilyn Hacker Julia Alvarez Amber Dermont Kimiko Hahn Yehuda Amichai Toi Derricotte Daniel Halpern Roger Angell Anita Desai Mohsin Hamid Max Apple Kiran Desai Patricia Hampl Rae Armantrout Junot Díaz Ron Hansen Margaret Atwood Natalie Diaz Michael S. Harper Paul Auster Joan Didion Robert Hass Toni Cade Bambara Annie Dillard John Hawkes Russell Banks Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni Terrance Hayes John Banville E. L. Doctorow Seamus Heaney Coleman Barks Anthony Doerr Anthony Hecht Julian Barnes Emma Donoghue Amy Hempel Andrea Barrett Mark Doty Cristina Henríquez Donald Barthelme Rita Dove Brenda Hillman Charles Baxter Denise Duhamel Edward Hirsch Ann Beattie Stephen Dunn Tony Hoagland Marvin Bell Stuart Dybek John Holman Diane Gonzales Bertrand Geoff Dyer Garrett Hongo Reginald Dwayne Betts Esi Edugyan Khaled Hosseini Frank Bidart Jennifer Egan Maureen Howard Chana Bloch Dave Eggers Richard Howard Amy Bloom Deborah Eisenberg Marie Howe Robert Bly Lynn Emanuel David Hughes Eavan Boland Nathan Englander John Irving Robert Boswell Anne Enright Kazuo Ishiguro T. C. Boyle Louise Erdrich Major Jackson David Bradley Martin Espada Marlon James Lucie Brock-Broido Jeffrey Eugenides Phyllis Janowitz Geraldine Brooks Irving Feldman Gish Jen Olga Broumas Nick Flynn Ha Jin Rosellen Brown Jonathan Safran Foer Denis Johnson Dennis Brutus Carolyn Forché Charles Johnson Bill Bryson Richard Ford Mat Johnson Frederick Busch Aminatta Forna Edward P.