Whitepaper Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 2016

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics October 2019, NCJ 251922 Bureau of Justice Statistics Bureau Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers, 2016 – Statistical Tables Connor Brooks, BJS Statistician s of the end of fscal-year 2016, federal FIGURE 1 agencies in the United States and Distribution of full-time federal law enforcement U.S. territories employed about 132,000 ofcers, by department or branch, 2016 Afull-time law enforcement ofcers. Federal law enforcement ofcers were defned as any federal Department of ofcers who were authorized to make arrests Homeland Security and carry frearms. About three-quarters of Department of Justice federal law enforcement ofcers (about 100,000) Other executive- provided police protection as their primary branch agencies function. Four in fve federal law enforcement ofcers, regardless of their primary function, Independent agencies worked for either the Department of Homeland · Security (47% of all ofcers) or the Department Judicial branch Tables Statistical of Justice (33%) (fgure 1, table 1). Legislative branch Findings in this report are from the 2016 0 10 20 30 40 50 Census of Federal Law Enforcement Ofcers Percent (CFLEO). Te Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted the census, collecting data on Note: See table 1 for counts and percentages. Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Census of Federal Law 83 agencies. Of these agencies, 41 were Ofces Enforcement Ofcers, 2016. of Inspectors General, which provide oversight of federal agencies and activities. Te tables in this report provide statistics on the number, functions, and demographics of federal law enforcement ofcers. Highlights In 2016, there were about 100,000 full-time Between 2008 and 2016, the Amtrak Police federal law enforcement ofcers in the United had the largest percentage increase in full-time States and U.S. -

Informer January 2017

Department of Homeland Security Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers Office of Chief Counsel Legal Training Division January 2017 THE FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT -INFORMER- A MONTHLY LEGAL RESOURCE AND COMMENTARY FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS AND AGENTS Welcome to this installment of The Federal Law Enforcement Informer (The Informer). The Legal Training Division of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers’ Office of Chief Counsel is dedicated to providing law enforcement officers with quality, useful and timely United States Supreme Court and federal Circuit Courts of Appeals reviews, interesting developments in the law, and legal articles written to clarify or highlight various issues. The views expressed in these articles are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers. The Informer is researched and written by members of the Legal Division. All comments, suggestions, or questions regarding The Informer can be directed to the Editor at (912) 267-3429 or [email protected]. You can join The Informer Mailing List, have The Informer delivered directly to you via e-mail, and view copies of the current and past editions and articles in The Quarterly Review and The Informer by visiting https://www.fletc.gov/legal-resources. This edition of The Informer may be cited as 1 INFORMER 17. Join THE INFORMER E-mail Subscription List It’s easy! Click HERE to subscribe, change your e-mail address, or unsubscribe. THIS IS A SECURE SERVICE. No one but the FLETC Legal Division will have access to your address, and you will receive mailings from no one except the FLETC Legal Division. -

Department and Agency Implementation Plans for the U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Department and Agency Implementation Plans for The U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This page intentionally left blank. Department and Agency Implementation Plans for The U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Acting Secretary’s Forward..................................................................6 Introduction........................................................................................8 Department/Agency Approach..........................................................9 Lines of Effort (“LOE”).....................................................................10 LOE 1: Participation.................................................................10 LOE 2: Protection and Access..................................................10 LOE 3: Internal U.S. Capabilities.............................................11 LOE 4: Partner Support............................................................12 Process/Cross Cutting........................................................................13 Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning.............................................13 6 | Department of Homeland Security Acting Secretary’s Forward In 2017, President Donald J.Trump signed a frst of its kind law recognizing the essential role of women around the world in promoting peace, maintaining security, and preventing confict and abuse.The Women, Peace, and Security Act of 2017 (WPS Act) advances opportunities for women to participate in these efforts—both at home -

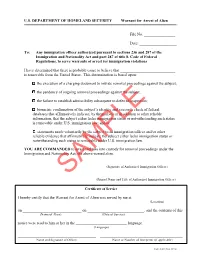

Warrant for Arrest of Alien

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Warrant for Arrest of Alien File No. ________________ Date: ___________________ To: Any immigration officer authorized pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and part 287 of title 8, Code of Federal Regulations, to serve warrants of arrest for immigration violations I have determined that there is probable cause to believe that ____________________________ is removable from the United States. This determination is based upon: the execution of a charging document to initiate removal proceedings against the subject; the pendency of ongoing removal proceedings against the subject; the failure to establish admissibility subsequent to deferred inspection; biometric confirmation of the subject’s identity and a records check of federal databases that affirmatively indicate, by themselves or in addition to other reliable information, that the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law; and/or statements made voluntarily by the subject to an immigration officer and/or other reliable evidence that affirmatively indicate the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law. YOU ARE COMMANDED to arrest and take into custody for removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act, the above-named alien. __________________________________________ (Signature of Authorized Immigration Officer) __________________________________________ SAMPLE (Printed Name and Title of Authorized Immigration Officer) Certificate of Service I hereby certify that the Warrant for Arrest of Alien was served by me at __________________________ (Location) on ______________________________ on _____________________________, and the contents of this (Name of Alien) (Date of Service) notice were read to him or her in the __________________________ language. -

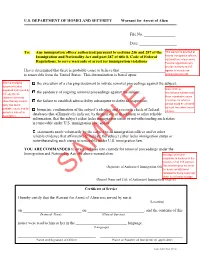

Ice Warrant of Arrest

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Warrant for Arrest of Alien File No. ________________ Date: ___________________ To: Any immigration officer authorized pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and part 287 of title 8, Code of Federal Regulations, to serve warrants of arrest for immigration violations I have determined that there is probable cause to believe that ____________________________ is removable from the United States. This determination is based upon: the execution of a charging document to initiate removal proceedings against the subject; the pendency of ongoing removal proceedings against the subject; the failure to establish admissibility subsequent to deferred inspection; biometric confirmation of the subject’s identity and a records check of federal databases that affirmatively indicate, by themselves or in addition to other reliable information, that the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law; and/or statements made voluntarily by the subject to an immigration officer and/or other reliable evidence that affirmatively indicate the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law. YOU ARE COMMANDED to arrest and take into custody for removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act, the above-named alien. __________________________________________ (Signature of Authorized Immigration Officer) __________________________________________ SAMPLE (Printed Name and Title of Authorized Immigration Officer) Certificate of Service I hereby certify that the Warrant for Arrest of Alien was served by me at __________________________ (Location) on ______________________________ on _____________________________, and the contents of this (Name of Alien) (Date of Service) notice were read to him or her in the __________________________ language. -

The Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act Instruction

Department of Homeland Security DHS Directives System Instruction Number: 257-01-001 Revision Number: 01 Issue Date: 01/18/2018 THE LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS SAFETY ACT INSTRUCTION I. Purpose This Instruction implements the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Directive 257-01, Rev. 1 “Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act” and establishes the procedures with respect to qualified retiring, retired, separated and separating law enforcement officers1 and the application of the relevant provisions of the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act (LEOSA), as amended. II. Scope This Instruction applies throughout the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to “qualified retired law enforcement officers” as set forth in LEOSA. This Instruction applies to DHS Components' handling of LEOSA matters with such individuals who meet the definition of a “qualified retired law enforcement officer” who have retired or separated from DHS Components since DHS was formed in 2003; with future such individuals; and with such individuals from predecessor agencies when these individuals make LEOSA inquiries with appropriate DHS successor Components. III. Authorities A. Title 18, United States Code (U.S.C.) § 926C, “Carrying of Concealed Firearms by Qualified Retired Law Enforcement Officers” [Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act of 2004, as amended] B. Title 18, U.S.C. § 922, “Unlawful Acts” 1 The 2017 DHS Lexicon defines a law enforcement officer as: Position occupied by an employee who is authorized by statute to enforce the laws of the United States, carry firearms, and make criminal arrests in the performance of their assigned duties. Includes designated U.S. Coast Guard officers and members. 1 Instruction # 257-01-001 Revision # 01 IV. -

Dhs-Accomplishments-Fact-Sheet.Pdf

Office of Public Affairs U.S. Department of Homeland Security Homeland Security Starts with Hometown Security As Secretary Napolitano said in the inaugural “State of America’s Homeland Security” address in January, our nation is more secure than it was two years ago, and more secure than when DHS was founded eight years ago. All of our efforts are guided by a simple but powerful, idea ‐‐ homeland security begins with hometown security. We are all safer when local law enforcement works together with the communities and citizens they serve, and their partners in the Federal government and the private sector, to protect against the threats we face. Since it was formed in 2003, DHS has achieved significant progress across its key mission areas: preventing terrorism, securing our borders; enforcing our immigration laws; securing cyberspace; and ensuring resilience to disasters: Preventing terrorism and enhancing security. Protecting the United States from terrorism is the cornerstone of homeland security. Most recently, in January 2011, Secretary Napolitano announced the new National Terrorism Advisory System (NTAS), which will more effectively communicate information about terrorist threats by providing timely, detailed information to the public, government agencies, first responders, airports and other transportation hubs, and the private sector. DHS has also led a global initiative to strengthen the international aviation system through partnerships with governments and industry, investments in new technology, and enhanced international standards and targeting measures. In November 2010, the Department fulfilled a key 9/11 Commission recommendation by fully implementing Secure Flight, under which the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) checks 100 percent of passengers on flights within or bound for the United States against government watchlists. -

Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act

Department of Homeland Security DHS Directives System Directive Number: 257-01 Revision Number: 01 Issue Date: 12/22/2017 LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS SAFETY ACT I. Purpose This Directive establishes policy with respect to qualified retiring, retired, separated and separating law enforcement officers1 and the application of the relevant provisions of the Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act of 2004 (LEOSA), as amended. II. Scope This Directive applies throughout the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to “qualified retired law enforcement officers” as set forth in LEOSA. This Directive applies to DHS Components' handling of LEOSA matters with such individuals who meet the definition of a “qualified retired law enforcement officer” who have retired or separated from DHS Components since DHS was formed in 2003; with future such individuals; and with such individuals from predecessor agencies when these individuals make LEOSA inquiries with appropriate DHS successor Components. III. Authorities A. Title 18, United States Code (U.S.C.) § 926C, “Carrying of Concealed Firearms by Qualified Retired Law Enforcement Officers” [Law Enforcement Officers Safety Act of 2004, as amended] B. Title 18, U.S.C. § 922, “Unlawful Acts” IV. Responsibilities A. The Under Secretary for Strategy, Policy, and Plans provides oversight of DHS policies related to LEOSA. B. Component heads that have qualified retired law enforcement officers: 1. Implement this Directive within their respective Components, to include coordinating any Component-developed LEOSA policy with the Office of Policy, Law Enforcement Policy and the Office of the General Counsel for concurrence; and 1 The 2017 DHS Lexicon defines a law enforcement officer as: Position occupied by an employee who is authorized by statute to enforce the laws of the United States, carry firearms, and make criminal arrests in the performance of their assigned duties. -

US Customs and Border Protection's Powers and Limitations

Legal Sidebari U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Powers and Limitations: A Brief Primer December 9, 2020 U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), a component of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), enforces federal customs and immigration laws at or near the international border and at U.S. ports of entry. Congress has established a comprehensive framework enabling CBP officers to inspect, search, and detain individuals to ensure their entry and any goods they import conform to these governing laws. That authority is not absolute. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits government searches and seizures that are not reasonable. While the government has broader latitude to conduct searches at the border than in the interior of the United States, these searches must still satisfy Fourth Amendment requirements. This Legal Sidebar briefly explains CBP’s customs and immigration enforcement powers and the constitutional limitations to that authority. (A separate DHS component, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE], is primarily responsible for immigration and customs enforcement in the interior of the United States; a discussion of ICE’s enforcement powers can be found here.) Many topics covered in this Sidebar are more extensively discussed in CRS Report R46601, Searches and Seizures at the Border and the Fourth Amendment, by Hillel R. Smith and Kelsey Y. Santamaria. Background The Homeland Security Act of 2002 established CBP as the component within DHS mainly responsible for protecting the nation’s international borders through enforcing federal customs and immigration laws (CBP also enforces other laws relating to the border, including those concerning the introduction of harmful plant or animal species and public health requirements). -

HSI Special Agent Brochure

Typical Enforcement Areas Money Laundering: Special agents identify, track, disrupt and dismantle the systems and criminal organizations that launder money generated from smuggling, trade fraud and/or export violations. Fraud Investigations: Special agents identify and target illicit trade practices that negatively impact the United States. Counter-Proliferation Investigations: Special agents investigate trafficking in a host of illegal commodities and components, including arms, controlled substances and the building blocks for nuclear, chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction. Agents also enforce international embargoes and sanctions imposed by other government agencies. Cyber Investigations: Special agents initiate online investigations to facilitate enforcement of any of the 400+ laws within the agency’s scope of authority where perpetrators use the Internet as a tool for criminal activities. Narcotics: Special agents use unified intelligence, HSI Special interdiction and investigative efforts to penetrate and dismantle drug smuggling organizations and reduce the flow of narcotics across U.S. borders. Agents Immigration and Nationality Act Violations: Homeland Security Investigations Special agents plan and conduct investigations, often undercover, concerning possible violations Make a Meaningful of criminal and administrative provisions of the act Difference in the World and other related statutes. Special HSI Investigates: • Threats to National Security and Public Safety Agents • Human Smuggling and Trafficking • Drug Smuggling Investigate the Possibilities • Counter-Proliferation Investigations • Gang Investigations • Financial and Money-Laundering Report Suspicious Activity: Crimes 1 -866-DHS-2-ICE • Customs Trade Fraud 1-866-DHS-2423 • Immigration Fraud www.ice.gov • Cyber and Child Exploitation Crimes ICE is an Equal Opportunity Employer 02/2011 Become an HSI Special Agent U.S. -

Report of the Subcommittee on Privatized Immigration Detention

HOM E LA N D SE CU R I T Y A DV IS OR Y COU NC I L Report of the Subcommittee on Privatized Immigration Detention Facilities December 1, 2016 This page is intentionally left blank. This publication is presented on behalf of the Homeland Security Advisory Council, Privatized Immigration Detention Facilities Subcommittee, chaired by Administrator (Ret.) Karen Tandy, Drug Enforcement Administration as the final report and recommendations to the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, Jeh C. Johnson. _________________________________ Karen Tandy Administrator (Ret.) Drug Enforcement Administration This page is intentionally left blank. PRIVATIZED IMMIGRATION DETENTION FACILITIES SUBCOMMITTEE MEMBERS Karen P. Tandy (Chair) – Former Administrator, Drug Enforcement Administration Marshall Fitz – Senior Fellow, Center for American Progress; Managing Director of Immigration, Emerson Collective Kristine Marcy – Vice Chairman, Board of Directors, National Academy of Public Administration Christian Marrone – Vice President for External Affairs and Chief of Staff to the CEO, CSRA Inc. David A. Martin – Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Virginia William H. Webster – (ex-officio) Retired Partner, Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP HOMELAND SECURITY ADVISORY COUNCIL STAFF Sarah E. Morgenthau, Executive Director, Homeland Security Advisory Council Erin Walls, Director, Homeland Security Advisory Council Victor de León, Staff, Homeland Security Advisory Council This page is intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ -

DHS Law Enforcement Components Did Not Consistently Collect DNA from Arrestees

DHS Law Enforcement Components Did Not Consistently Collect DNA from Arrestees May 17, 2021 OIG-21-35 OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Department of Homeland Security Washington, DC 20528 / www.oig.dhs.gov May , 2021 MEMORANDUM FOR: The Honorable Alejandro Mayorkas Secretary Department of Homeland Security FROM: Joseph V. Cuffari, Ph.D. Digitally signed by JOSEPH V JOSEPH V CUFFARI Inspector General Date: 2021.05.14 CUFFARI 12:03:28 -04'00' SUBJECT: DHS Law Enforcement Components Did Not Consistently Collect DNA from Arrestees Attached for your information is our final report, DHS Law Enforcement Components Did Not Consistently Collect DNA from Arrestees. We incorporated the formal comments provided by your office. The report contains four recommendations aimed at improving DNA collection by the Department of Homeland Security. Your office concurred with all four recommendations. Based on the information you provided in your response to the draft report, we consider recommendations 1, 2, and 3 open and resolved. Once your office has fully implemented the recommendations, please submit a formal closeout letter to us within 30 days so that we may close the recommendations. The memorandum should be accompanied by evidence of completion of agreed-upon corrective actions. Recommendation 4 is resolved and closed. Please send your response or closure request to [email protected]. Consistent with our responsibility under the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, we will provide copies of our report to congressional committees with oversight and appropriation responsibility over the Department of Homeland Security. We will post the report on our website for public dissemination.