Diagram One Shot 1 Shot 2 Shot 3 A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1994 Ball, Draw a Line Perpendicular to El-E, and Extend It Until It Meets the Extended Path of the Object Ball at E2

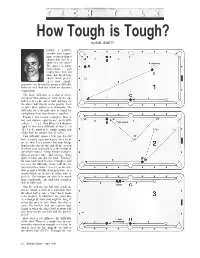

How Tough is Tough? by BOB JEWETT DOES A LONG, straight shot require more accuracy than a shorter thin cut? Is a bank or a cut easier? The answer is partly individual; you might love thin cut shots but dread long shots. Such prefer- ences aside, simple geometry can be used to assign a difficulty factor to each shot and allow an objective comparison. The basic difficulty of a shot is deter- mined by two distances: how far the cue ball travels to the object ball and how far the object ball travels to the pocket. Let's measure these distances in diamonds. The difficulty on a straight shot is found by multiplying these two distances together. Figure 1 has several examples. Shot A has each distance equal to one, so its diffi- culty is 1 = 1 x 1. Shot B has each distance equal to two for a difficulty of four. C, at 12 (3 x 4), starts to be tough enough you might look for another shot or safety. This difficulty number tells you directly how accurate your mechanics have to be on the shot. Let's assume that your bridge hand is placed perfectly, and all the error is in where your grip hand is at the instant of tip-to-ball impact. Using similar triangles, typical pocket size, and average wing span, it turns out that the total "window" for your back hand to come through is just one over the difficulty factor, with the an- swer in inches. Shot C is a 12, so the win- dow is only a twelfth of an inch wide, or a twenty-fourth of an inch to either side of perfect. -

Willie Hoppe Regains Billiard Championship, Defeating Schaefer 500 to 283 in Final Match Spectacular Play of Former Mcgraw Is Set the Teams Still in P.C.A

Willie Hoppe Regains Billiard Championship, Defeating Schaefer 500 to 283 in Final Match Spectacular Play of Former McGraw Is Set The Teams Still in P.C.A. Plans Title Holder Overcomes Lead For an Earful Gridiron Circuit Tie for Qualifying Play .-By w. B# HANNA-*-. Squash By Sections for National Open Runs 188 in Eleventh and Ends Match in On California! With Harvard and Yale seeking their way back Into the sunlight after Tennis ft Honors inning sojourn in the shadows of defeat, and life brightening- up once more, the By Ray McCarthy Next to Conti Beats and rivais for The Trip Table; Horcmaus. Coast League Missionaries Army Navy, the limelight next «Saturday, and with no executive committee of the Professional Golfer*' Aswwift-tim had 500 to 303, and Third recent defeats to repine, are buckling on their armor. As with most ö. K. E. Beats Crescent AC. ; ri long .session at headquarters yesterday, dividing the country into two parts Captures Prke Here to Boost State elevens this individual stars at West Yale for the of for 1923 fall, Point and Annapolis arc con¬ and Harvard Club purpose qualifying contestants for the national open champion¬ By Fred Hawthorne Training Camp spicuous by their absence. There has been a conspicuous absence of out¬ Class B Players Also Win ship at Inwood next spring. The committee didn't actually divida the standing players this year, and a greater number of men country as a government might do.it named the states "»hose Willie Hoppe, of New York, regained his world's championship title Kieran correspondingly simply golf billiards last By John who are but part of the various wholes. -

![Arxiv:2104.11232V2 [Nlin.CD] 29 Apr 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1448/arxiv-2104-11232v2-nlin-cd-29-apr-2021-3271448.webp)

Arxiv:2104.11232V2 [Nlin.CD] 29 Apr 2021

Motions of a billiard ball after a cue stroke Hyeong-Chan Kim1 1School of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Korea National University of Transportation, Chungju, 27469, Korea∗ We study the collision between the cue and the ball in the game of billiards. After studying the collision process in detail, we write the (rotational) velocities of the ball and the cue after the collision. We also find the squirt angle of the ball for an oblique collision which represents the deviation of the ball from the intended direction. I. INTRODUCTION In 1835, Coriolis [1] studied the mathematical analysis of billiards for the first time. To my knowledge, it takes more than one century for another work for the billiard games based on physics [2]. In Refs. [3,4], the authors considered the effect of friction on collisions of billiard balls in 2-dimensions. In Ref. [5], Han studied various aspects of the billiard physics. Mathavan used a fast camera to analyze the ball motions in the billiard games [6] and studied the motion of the ball under cushion impact [7]. The billiard models were also used to develop a robotics system [8]. A cue stroke on a billiard ball makes the ball run along the line of cue incidence. This ordinary point of view in billiards games is correct for a head-on collision only between the ball and the cue. Coriolis [1] calculated the outcome of the collision based on a coefficient of restitution (COR) when the cue strikes the ball's center with zero impact parameter. Here, the COR is defined based on the head-on collision. -

Mechanics of Billiards, and Analysis of Willie Hoppe's Stroke

MECHANICS OF BILLIARDS, AND ANALYSIS OF WILLIE HOPPE'S STROKE A. D. MOORE Professor of Electrical Engineering College of Engineering University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan January 17, 1942 January 6, 1947: Additional Notes. Since writing the manuscript five years ago, some additional facts have come to light, and should be mentioned here. At the bottom of the page, page 26, it is concluded that the cue ball initial velocity, in the nine-cushion shot, is no more than in the break shot. This is wrong. Hoppe and Cochran both say that the nine-cushion shot takes a much harder stroke. Al¬ though I have never managed to make this shot, my attempts at it force me to agree. I went wrong in my analysis by assuming that the flash interval in the Life photographs was the same for all shots. As it turns out, the apparatus (which I have learned was built at Bell Lab¬ oratories by a former student of mine!) was adjustable: for any one shot, the best flash interval for recording that shot could be used. On page 39, I stated certain conclusions about the bridge, and tightness of the bridge. Since studying neuromuscular phenomena, and after recording my own stroke and analyzing it, I conclude that the most important function of the professional's tight bridge is to furnish a constant resistance to cue movement. This, in turn, requires him to shoot tetanically. That is, the stroking muscles are in a constant state of contraction while accelerating the cue. My theory is that only in this was can one master the "velocity" part of the game, and reliably impart to the cue ball the desired velocity, in order to play position. -

Greenleaf Vs. Brunswick Pool’S Bad Boy Vs

UNTOLD STORIES: GREENLEAF VS. BRUNSWICK POOL’S BAD BOY VS. BRUNSWICK Jilted Greenleaf fi led suit for $100K in industry row. Story by R.A. Dyer N NOV. 5, 1946, at precisely 10:35 not the company, that barred Greenleaf. Welcome back to Untold Stories. This a.m., pool superstar Ralph Green- Brunswick further alleged that Green- month’s installment is about that fasci- O leaf sent a short telegram to table- leaf was barred from the tournament nating $100,000 lawsuit, 282 pages of maker Brunswick-Balke-Collender Co. not for any improper monopolistic rea- which I managed to dig up after several It was written in all caps — which I sons, but because the former champion long-distance phone calls and discus- know is how such things were writ- had acted deplorably during previous sions with various archivists and reviews ten back then — but it nonetheless matches. of newspaper clippings. Although it’s gives the note an appropriately IMAGE COURTESY THE BILLIARD ARCHIVE unclear how the lawsuit turned breathless feel. out — I imagine it was probably This is what it said: settled or dropped — the papers “HAVE BEEN PLAYING BY do provide a fascinating glimpse FAR BEST POCKET BILLIARDS of some of the behind-the-cur- OF MY CAREER IN MATCHES tains ugliness of the pool world. RIGHT IN PHILADELPHIA One document also provides a WHERE TOURNAMENT IS TO rough timeline of Greenleaf’s BE PLAYED. ALSO HAD GOOD professional career, which is the PUBLICITY ON SAME. ALSO fi rst I’ve ever come across. IN BEST SHAPE OTHERWISE This month’s column is mostly EXPECT TO BE IN TOUR- based on those court records, NAMENT. -

St. Jean Could Beat Greenleaf, but Not the Bottle. Story by R.A

UNTOLD STORIES: ANDREW ST. JEAN ALL THAT TALENT SQUANDERED St. Jean could beat Greenleaf, but not the bottle. Story by R.A. Dyer HIS IS the story of Ralph Greenleaf’s of booze and gambling, and was treach- Desell that they lost track of St. Jean drinking partner, a man who was erous as a player and extremely skilled. over the years, although one recalled T a gambler and a contender for the He was said to have the ability to run seeing him play against Willie Hoppe national championship. He was a hell- 70 balls one-handed and during his during the 1920s. St. Jean also was said raiser of the old school — of the very old later years made his living playing three- to frequent a social club in Lowell popu- school — a product of Prohibition and cushion billiards with only one hand. lar with French-Canadians. It’s called of the Roaring ’20s. Sometimes he wore It was cirrhosis that killed him. He the Pastetempe Club and it’s still there a tuxedo, sometimes a mask. He almost was buried in his hometown of Lowell, in downtown, looking pretty much the always carried a fl ask. Mass. (also the home of Jack Kerouac), same as always. “He was dyed-in-the- Welcome back to Untold Stories. PHOTOS COURTESTY OF THE BILLIARD ARCHIVE This month I’m profi ling Andrew St. Jean, one of the most colorful almost-champions of our most col- orful sport. In 1928, St. Jean was runner-up for the title, being bested only by the great Greenleaf himself. -

Personnel and Procedures. There Is a Checklist of Arrangements for Planning and Conducting .Tournaments

DOCUMONTROSUNI ED 028 478 By-Stevens. George F. The Union Recreation Areft Cdlege Unions at Work. Association of College Unions-International. Ithaca. N.Y. Pub Date 65 Note-47p. Avalable from-Association. of College *UnionsInternational. Willard StaigM Hall. Cornell University. Ithaca. New York 14850 EDRS Price MF4025 HC-S2.45 Descriptors-*CocurricularActivities. Games, NoninstructionalResponsibility.RecreatiofialActivities, RecreationalFacilities. Recreational Programs. Recreation Finances. S Social Recreation Programs. *Student Unions , Within the context of college union programs. the recreational games of bowling. billiards, table tennis. and some table games are discussed. including their history. facilities, and operation. Specific duties and responsibilities of the Recreation Area Manager are outlined. as are counter personnel and procedures. and maintenance personnel and procedures. There is a checklist of arrangements for planning and conducting .tournaments. Included in the appendix are: amateur standing policy. materials for game promotion. director of games associations, key bowling lane dimensions, billiard taL'e specifications, table tennis-table specifications, and regions of the Association of College Unions--International. (I(P) ger CO COLLEGEUNIONS E AT WOR K 44/4410# 50TH ANNIVER iaktrW1 MONOGRAPH SE qk OF THEASSOCIATILi OF COLLEGEUNION INTERNATIONAL gbh TheUnion RecreationArea ByGEORGE F.STEVENS ROLE OF THECOLLEGE UNION "I. The union is the communitycenter of the college,for all the members of the college family students, faculty, administration, alumni, and guests. It is not just abuilding; it is also an organization and. a program. Together they represent awell-considered plan for the community life of thecollege. "2. As the 'living room' orthe hearthstone' of the college,the union provides for theservices, conveniences, andamenities the members of the college familyneed in their daily life on the campus and for getting to know andunderstand one another throughinformal association outside theclassroom. -

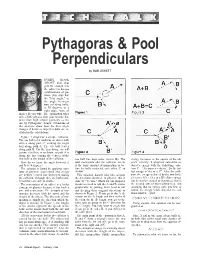

Pythagoras & Pool Perpendiculars

Pythagoras & Pool Perpendiculars by BOB JEWETT EVERY BOOK ABOUT pool that gets far enough into the subject to discuss combinations or po- sition play says that the "kiss angle," or the angle between two colliding balls, is 90 degrees or a right angle. None of them tells you why. The explanation takes only a little physics plus your favorite the- orem from high school geometry — the one by Pythagoras. Simple extensions of the analysis show how the kiss angle changes if throw or imperfect balls are in- cluded in the calculations. Figure 1 diagrams a simple collision. The cue ball (or it might be an object ball) arrives along path C, sending the target ball along path A. The cue ball leaves along path B. For the time being, we will assume that there is no throw, so path A is along the line joining the centers of the two balls at the instant of the collision. cue ball has kept some (arrow B). The energy increases as the square of the ob- How do we know the angle between A total momentum after the collision. A+ B, ject's velocity. A physicist calculates an and B is 90 degrees? is the same amount of momentum as be- object's energy with the following equa- The solution is found by applying basic fore the balls contacted each other, C, so tion: E = 'A x mass x velocity2. So the ini- laws of physics: momentum and energy A+B=C. tial energy is 'A x m x C2. After the colli- are neither created nor destroyed during This equation doesn't take into account sion, the energy is shared by the two balls, the collision, although they are both trans- the directions involved.