Seafood Watch Seafood Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Factors Affecting Growth of the Spiny Lobsters Panulirus Gracilis and Panulirus Inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) in Guerrero, México

Rev. Biol. Trop. 51(1): 165-174, 2003 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Factors affecting growth of the spiny lobsters Panulirus gracilis and Panulirus inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) in Guerrero, México Patricia Briones-Fourzán and Enrique Lozano-Álvarez Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Unidad Académica Puerto Morelos. P. O. Box 1152, Cancún, Q. R. 77500 México. Fax: +52 (998) 871-0138; [email protected] Received 00-XX-2002. Corrected 00-XX-2002. Accepted 00-XX-2002. Abstract: The effects of sex, injuries, season and site on the growth of the spiny lobsters Panulirus gracilis, and P. inflatus, were studied through mark-recapture techniques in two sites with different ecological characteristics on the coast of Guerrero, México. Panulirus gracilis occurred in both sites, whereas P. inflatus occurred only in one site. All recaptured individuals were adults. Both species had similar intermolt periods, but P. gracilis had significantly higher growth rates (mm carapace length week-1) than P. inflatus as a result of a larger molt incre- ment. Growth rates of males were higher than those of females in both species owing to larger molt increments and shorter intermolt periods in males. Injuries had no effect on growth rates in either species. Individuals of P. gracilis grew faster in site 1 than in site 2. Therefore, the effect of season on growth of P. gracilis was analyzed separately in each site. In site 2, growth rates of P. gracilis were similar in summer and in winter, whereas in site 1 both species had higher growth rates in winter than in summer. -

Redalyc.Occurrence of Panulirus Inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae

Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía ISSN: 0717-3326 [email protected] Universidad de Valparaíso Chile Pérez-González, Raúl; Puga, Dagoberto; Valadez, Luis M.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, Guillermo Occurrence of Panulirus inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) pueruli in the southeastern Gulf of California, Mexico Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, vol. 51, núm. 1, abril, 2016, pp. 223-227 Universidad de Valparaíso Viña del Mar, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=47945599023 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía Vol. 51, Nº1: 209-215, abril 2016 DOI 10.4067/S0718-19572016000100023 RESEARCH NOTE Occurrence of Panulirus inflatus (Decapoda: Palinuridae) pueruli in the southeastern Gulf of California, Mexico Presencia de puérulos de Panulirus inflatus (Bouvier, 1895) (Decapoda: Palinuridae) en el sureste del golfo de California, México Raúl Pérez-González1, Dagoberto Puga2, Luis M. Valadez1 and Guillermo Rodríguez-Domínguez1 1Facultad de Ciencias del Mar, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, Paseo Claussen s/n, C.P. 82000, Apdo. Postal 610, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. [email protected] 2Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Centro Regional de Investigación Pesquera de Bahía Banderas, Nayarit. Calle Tortuga No. 1, La Cruz de Huanacaxtle, C.P. 63732, Nayarit, México Abstract.- This study presents results on the collection of Panulirus inflatus pueruli in seaweed (GuSi; set at the surface) and crevice (Booth: set on the bottom) collectors from April to December 1998 in waters of the southeastern Gulf of California, Mexico. -

Growth Patterns and Exploitation Status of the Spiny Lobster Species Palinurus Mauritanicus (Gruvel 1911) in Mauritanian Coasts

International Journal of Agricultural Policy and Research Vol.7 (2), pp. 17-31, March 2019 Available online at https://www.journalissues.org/IJAPR/ https://doi.org/10.15739/IJAPR.19.003 Copyright © 2019 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN 2350-1561 Original Research Article Growth patterns and exploitation status of the spiny lobster species Palinurus mauritanicus (Gruvel 1911) in Mauritanian coasts Received 3 January, 2019 Revised 10 February, 2019 Accepted 15 February, 2019 Published 14 March, 2019 Amadou Sow1, In the Mauritanian coasts, fishing effort on Palinurus mauritanicus Bilassé Zongo*2 contributes in the decline of the stock. From February to August 2015, samplings were carried out monthly in order to study the growth patterns and and the stock status to provide further information for sustainable 2 T. Jean André Kabre management and exploitation of the species. A total of 12008 individuals were collected. Total length (Lt) and cephalothoracic length (Lc) were 1Institut Mauritanien des measured with a vernier caliper. The species were separately weighed on a Recherches Océanographiques et digital balance and their sex noted. The collected data were entered on excel des Pêches (IMROP), Mauritanie spreadsheet in order to analyse growth kinetics, exploitation kinetics and 2Université Nazi Boni, LaRFPF, estimate fish mortality using FISAT II software. Male of P. mauritanicus had Burkina Faso an average Lc = 130 mm and an average Lc = 111 mm. The annual length frequency distribution gave respectively 6 and 7 age-groups for females and *Corresponding Author males. Lc-Lt relationship and Lc-Wt relationship showed a minor allometry Email: [email protected] (b < 3 for both). -

The Biology and Fisheries of the Slipper Lobster

The Biology and Fisheries of the Slipper Lobster Kari L. Lavalli College of General Studies Boston University Bo~ton, Massachusetts, U.S.A. Ehud Spanier The Leon Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies and Department of Maritime Civilizations University of Haifa Haifa, Israel 0 ~y~~F~~~~~oup Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Cover image courtesy of Megan Elizabeth Stover of the College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2007 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-8493-3398-9 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-8493-3398-9 (Hardcover) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission, and sources are indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the validity of all materials or for the consequences of their use. No part ofthis book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any informa tion storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. -

Samoan Crab Regulations

State of Hawaii DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Aquatic Resources Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 October 11, 2019 Board of Land and Natural Resources State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii REQUEST FOR APPROVAL TO HOLD PUBLIC MEETINGS AND HEARINGS TO REPEAL HAWAII ADMINISTRATIVE RULES (HAR) TITLE 13 CHAPTERS 84 AND 89 AND TO AMEND AND COMPILE HAR TITLE 13 CHAPTER 95, TO UPDATE AND CONSOLIDATE RULES AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS REGULATING THE TAKE, POSSESSION, AND SALE OF SAMOAN CRAB, KONA CRAB, AND LOBSTER Submitted for your consideration and approval is a request to hold public meetings and hearings to repeal Hawaii Administrative Rules (HAR) chapters 13-84 and 13-89 and to amend and compile HAR chapter 13-95 to update and consolidate rules and statutory provisions regulating the take, possession, and sale of Samoan crab, Kona crab, and lobster. BACKGROUND Regulations for the take, possession, and sale of Samoan crab, Kona crab, and certain species of lobster are found in various sections of the HAR and Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS). These regulations are summarized below. Samoan crab regulations HAR chapter 13-84, “Samoan Crab”, was adopted in 1981 based substantially upon regulations of the Department’s former Division of Fish and Game. It prohibits the taking, killing, possession, or sale of any Samoan crab carrying eggs externally, or less than six inches in carapace width. HAR §13-95-52, adopted in 1998, also prohibits the take, killing, possession, or sale of any Samoan crab with eggs. In addition, it prohibits the take or killing of any Samoan crab with a spear, as well as sale of any speared Samoan crab. -

Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop

Special Report No. 75 of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop October 2002 Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop October 2002 Edited by Heather M. Stirratt Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission Convened by: Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission August 26, 2002 Washington, DC Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop ii Preface This document was prepared in cooperation with the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s American Lobster Management Board, Technical Committee, Plan Development Team, Stock Assessment Subcommittee and the Advisory Panel. A report of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission pursuant to U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA17FG2205. Proceedings of the American Lobster Transferable Trap Workshop iii Acknowledgments This report is the result of a Workshop on transferable trap programs for American lobster which was held on August 26, 2002, in Washington, DC. The workshop was convened and organized by a Workshop Steering Committee composed of: David Spencer (Advisory Panel, Chair), George Doll (New York Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), John Sorlien (Rhode Island Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), Todd Jesse (Massachusetts Commercial Lobsterman, Advisory Panel Member), Ernie Beckwith (Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection), Mark Gibson (Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management), -

Slipper Lobsters (Scyllaridae) Off the Southeastern Coast of Brazil: Relative Growth, Population Structure, and Reproductive

55 Abstract—The hooded slipper lobster Slipper lobsters (Scyllaridae) off the (Scyllarides deceptor) and Brazilian slipper lobster (S. brasiliensis) are southeastern coast of Brazil: relative growth, commonly caught by fishing fleets (with double-trawling and longline population structure, and reproductive biology pots and traps) off the southeastern coast of Brazil. Their reproductive Luis Felipe de Almeida Duarte (contact author)1 biology is poorly known and research 2 on these 2 species would benefit ef- Evandro Severino-Rodrigues forts in resource management. This Marcelo A. A. Pinheiro3 study characterized the population Maria A. Gasalla4 structure of these exploited species on the basis of sampling from May Email address for contact author: [email protected] 2006 to April 2007 off the coast of Santos, Brazil. Data for the abso- 1 Departamento de Zoologia 3 Laboratório de Biologia de Crustáceos lute fecundity, size at maturity in Ca[mpus de Rio Claro Grupo de Pesquisa em Biologia de Crustáceos females, reproductive period, and Universidade Estadual Paulista Ca[mpus Experimental do Litoral Paulista morphometric relationships of the Avenida 24 A, 1515 Universidade Estadual Paulista dominant species, the hooded slipper 13506-900, Rio Claro Praça Infante D. Henrique lobster, are presented. Significant São Paulo, Brazil s/n°11330-900, São Vicente differential growth was not observed 2 São Paulo, Brazil between juveniles and adults of each Instituto de Pesca 4 sex, although there was a small in- Agência Paulista de Tecnologia dos Laboratório de Ecossistemas Pesqueiros vestment of energy in the width and Agronegócios Departamento de Oceanográfico Biológica length of the abdomen in females Secretaria de Agricultura e Abastecimento Instituto Oceanográfico and in the carapace length for males Governo do Estado São Paulo Universidade de São Paulo in larger animals (>25 cm in total Avenida Bartolomeu de Gusmão, 192 Praça do Oceanográfico, 191 length [TL]). -

Stock Status Table

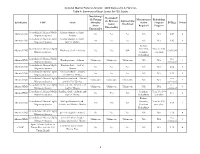

National Marine Fisheries Service - 2020 Status of U.S. Fisheries Table A. Summary of Stock Status for FSSI Stocks Overfishing? Overfished? (Is Fishing Management Rebuilding (Is Biomass Approaching Jurisdiction FMP Stock Mortality Action Program B/B Points below Overfished MSY above Required Progress Threshold?) Threshold?) Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.08 4 Migratory Species Atlantic Consolidated Atlantic Highly Atlantic sharpnose shark - Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.02 4 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico Reduce Consolidated Atlantic Highly Mortality, Year 8 of 30- Atlantic HMS Blacknose shark - Atlantic Yes Yes NA 0.43-0.64 1 Migratory Species Continue year plan Rebuilding Consolidated Atlantic Highly not Atlantic HMS Blacktip shark - Atlantic Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Blacktip shark - Gulf of Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 2.62 4 Migratory Species Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Finetooth shark - Atlantic Atlantic HMS No No No NA NA 1.30 4 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico Consolidated Atlantic Highly Great hammerhead - Atlantic not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species and Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Lemon shark - Atlantic and not Atlantic HMS Unknown Unknown Unknown NA NA 0 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico estimated Consolidated Atlantic Highly Sandbar shark - Atlantic and Continue Year 16 of 66- Atlantic HMS No Yes NA 0.77 2 Migratory Species Gulf of Mexico -

From Mangroves to Coral Reefs; Sea Life and Marine Environments in Pacific Islands by Michael King Apia, Samoa: SPREP 2004

SPREP fromto coral mangroves reefs sea life and marine environments in Pacific islands Michael King South Pacific Regional Environment Programme SPREP Cataloguing-in-Publication King, Michael From mangroves to coral reefs; sea life and marine environments in Pacific islands by Michael King Apia, Samoa: SPREP 2004 This handbook was commissioned by the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme with funding from the Canada South Pacific Ocean Development Program (C-SPODP) and the UN Foundation through the International Coral Reef Action Network (ICRAN) SPREP PO Box 240 Apia, Samoa Phone (685) 21929 Fax (685) 20231 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.sprep.org.ws From mangroves to coral reefs sea life and marine environments in Pacific islands ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction 1 6. The classification and diversity of marine life 29 Biological classification – naming things 2. Coastal wetlands - estuaries and mangroves 5 Diversity – the numbers of species Estuaries – where rivers meet the sea 7. Crustaceans – shrimps to coconut crabs 33 Mangroves – coastal forests Smaller crustaceans 3. Shorelines – beaches and seaplants 9 Shrimps and prawns Beaches – rivers of sand Lobsters and slipper lobsters Seaweeds – large plants of the sea Crabs Seagrasses – underwater pastures Hermit crabs and stone crabs 4. Corals - from coral polyps to reefs 15 8. Molluscs – clams to octopuses 41 Stony corals and coral polyps Clams, oysters, and mussels (bivalves) Fire corals – stinging hydroids Sea snails (gastropods) Corals in deepwater Octopuses and their relatives (cephalopods) Soft corals and gorgonians - octocorals 9. Echinoderms – sea cucumbers to sand dollars 51 Coral reefs – the world’s Sea cucumbers largest natural structures Sea stars 5. -

First Record of an Adult Galapagos Slipper Lobster, Scyllarides Astori

Azofeifa-Solano et al. Marine Biodiversity Records (2016) 9:48 DOI 10.1186/s41200-016-0030-9 MARINE RECORD Open Access First record of an adult Galapagos slipper lobster, Scyllarides astori, (Decapoda, Scyllaridae) from Isla del Coco, Eastern Tropical Pacific Juan Carlos Azofeifa-Solano1*, Manon Fourriére2,3 and Patrick Horgan4 Abstract The Galapagos Slipper lobster, Scyllarides astori, has been reported from rocky reefs along the Eastern Tropical Pacific: the Gulf of California, the Galapagos Archipelago and mainland Ecuador. Although larval stage S. astori has been found in other localities throughout this range, there are no records of adults inhabiting waters between these three locations. Here we present the first record of an adult S. astori from Isla del Coco and Costa Rican Pacific waters. The single specimen, a male, was hand-collected within a coral reef in Pájara islet. This finding increases the reported lobster species richness of Costa Rican Pacific waters to six species and expands the adult geographic range of S. astori to Isla del Coco. Keywords: Diversity record, Coral reefs, Scyllaridae, Oceanic island, Tropical waters, Costa Rica Introduction Hendrickx 1995). The Shield Fan Lobster (E. princeps)isdis- Marine lobsters are a highly diverse group that includes tributed along the Pacific coast from the Gulf of California six families, 55 genera, and 248 species that occupy a to Peru (Johnson 1975b; Holthuis 1985; Hendrickx 1995), wide range of habitats and are distributed worldwide while S. astori has been reported in the Gulf of California, (Chan 2014; Briones-Fourzán and Lozano-Álvarez 2015). the Galapagos Archipelago, nearby Clipperton atoll and The slipper lobsters (Scyllaridae) can be distinguished mainland Ecuador (Holthuis and Loesch 1967; Holthuis from other lobster families in the infraorder Achelata by 1991; Hendrickx 1995; Béarez and Hendrickx 2006; Butler having the antennal peduncle segments wide and flat, et al. -

Molecular Phylogeny and Seascape Genetics of the Panulirus Homarus Subspecies in the Western Indian Ocean

Molecular phylogeny and seascape genetics of the Panulirus homarus subspecies in the Western Indian Ocean By Sohana Singh (MSc Genetics) Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Life Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal Durban As the candidate’s supervisors we have approved this thesis/dissertation for submission. Signed: Name: Johan Groeneveld Date: 6 December 2017 Signed: Name: Sandi Willows-Munro Date: 5 December 2017 i Preface The work described in this dissertation was carried out at the Oceanographic Research Institute (ORI), which is affiliated with the School of Life Sciences at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville. The study was undertaken between February 2015 and December 2017, under the supervision of Professor Johan Groeneveld and co-supervision of Dr Sandi Willows-Munro. It represents original work by the author and has not otherwise been submitted in any form for any degree or diploma to any tertiary institution. Where use has been made of the work of others it is duly acknowledge in the text. Sohana Singh Signed _________________ Date 7 December 2017 Prof. Johan Groeneveld Signed Date 6 December 2017 Dr. Sandi Willows-Munro Signed Date 5 December 2017 ii Declaration 1 - Plagiarism I, Sohana Singh, declare that: The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons.