Integrating Preservation and Development at Yellowstone's Upper Geyser Basin, 1915–1940

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone Visitor Guide 2019

Yellowstone Visitor Guide 2019 Are you ready for your Yellowstone adventure? Place to stay Travel time Essentials Inside Hotels and campgrounds fill up Plan plenty of time to get to Top 5 sites to see: 2 Welcome quickly, both inside and around your destination. Yellowstone 1. Old Faithful Geyser 4 Camping the park. Make sure you have is worth pulling over for! 2. The Grand Canyon of the secured lodging before you make Plan a minimum of 40 minutes Yellowstone River 5 Activities other plans. If you do not, you to travel between junctions or 3. Yellowstone Lake 7 Suggested itineraries may have to drive several hours visitor service areas on the Grand 4. Mammoth Hot Springs away from the park to the nearest Loop Road. The speed limit in Terraces 8 Famously hot features available hotel or campsite. Yellowstone is 45 mph (73 kph) 5. Hayden or Lamar valleys 9 Wild lands and wildlife except where posted slower. 10 Area guides 15 Translations Area guides....pgs 10–14 Reservations.......pg 2 Road map.......pg 16 16 Yellowstone roads map Emergency Dial 911 Information line 307-344-7381 TTY 307-344-2386 Park entrance radio 1610 AM = Medical services Yellowstone is on 911 emergency service, including ambulances. Medical services are available year round at Mammoth Clinic (307- 344-7965), except some holidays. Services are also offered at Lake Clinic (307-242-7241) and at Old Faithful Clinic (307-545-7325) during the summer visitor season. Welcome to Yellowstone National Park Yellowstone is a special place, and very different from your home. -

Human Impacts on Geyser Basins

volume 17 • number 1 • 2009 Human Impacts on Geyser Basins The “Crystal” Salamanders of Yellowstone Presence of White-tailed Jackrabbits Nature Notes: Wolves and Tigers Geyser Basins with no Documented Impacts Valley of Geysers, Umnak (Russia) Island Geyser Basins Impacted by Energy Development Geyser Basins Impacted by Tourism Iceland Iceland Beowawe, ~61 ~27 Nevada ~30 0 Yellowstone ~220 Steamboat Springs, Nevada ~21 0 ~55 El Tatio, Chile North Island, New Zealand North Island, New Zealand Geysers existing in 1950 Geyser basins with documented negative effects of tourism Geysers remaining after geothermal energy development Impacts to geyser basins from human activities. At least half of the major geyser basins of the world have been altered by geothermal energy development or tourism. Courtesy of Steingisser, 2008. Yellowstone in a Global Context N THIS ISSUE of Yellowstone Science, Alethea Steingis- claimed they had been extirpated from the park. As they have ser and Andrew Marcus in “Human Impacts on Geyser since the park’s establishment, jackrabbits continue to persist IBasins” document the global distribution of geysers, their in the park in a small range characterized by arid, lower eleva- destruction at the hands of humans, and the tremendous tion sagebrush-grassland habitats. With so many species in the importance of Yellowstone National Park in preserving these world on the edge of survival, the confirmation of the jackrab- rare and ephemeral features. We hope this article will promote bit’s persistence is welcome. further documentation, research, and protection efforts for The Nature Note continues to consider Yellowstone with geyser basins around the world. Documentation of their exis- a broader perspective. -

Local Old Faithful Area Ski

*See larger map for additional trails. Trail Descriptions Skiing in a geyser basin near thermal areas is an ex- Fern Cascades Loop Trail Skier-Tracked Trail - A trail that has been made/ citing and unusual experience. It also presents some 2.75 miles (4.4 km), most difficult, skier-tracked. broken by a person skiing through deep snow. challenges. Because of the heat below ground, sections Start at the Bear Den Ski Shop exit and angle of these trails are often bare of snow and you may need towards the Snow Lodge cabin area. Then the to remove your skis in order to continue. However, for trail goes through trees and crosses small bridges Machine-Groomed Trail - Mostly level trail with your own safety and the safety of other skiers, please to reach the main snow vehicle road. The trail machine set tracks; ideal conditions for beginners. do not remove your skis on steep, snow-covered trails. begins across the road. Bear right on this one- Groomed areas are for both classic and skate skiing. Skiing on boardwalks can be quite difficult and you way loop and follow under the power lines. If the Most of these are practice loops that follow summer may want to consider snowshoeing or walking along uphill section at the start of the trail is too steep, roads. In addition the Upper Geyser Basin Trail those routes. turn around. The trail only gets more difficult from from the lower store to Morning Glory Pool is there. The trail continues close to the bottom of the groomed but often has bare patches due to thermal heat. -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 27 number 1 • 2010 Origins Founded in 1980, the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to he the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROLF DIA.MANT, President • Woodstock, Vermont STEPHANIE T(K)"1'1IMAN, Vice President • Seattle, Washington DAVID GKXW.R, Secretary * Three Rivers, California JOHN WAITHAKA, Treasurer * Ottawa, Ontario BRAD BARR • Woods Hole, Massachusetts MELIA LANE-KAMAHELE • Honolulu, Hawaii SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming BRENT A. MITCHELL • Ipswich, Massachusetts FRANK J. PRIZNAR • Gaithershnrg, Maryland JAN W. VAN WAGTENDONK • El Portal, California ROBERT A. WINFREE • Anchorage, Alaska Graduate Student Representative to the Board REBECCA E. STANFIELD MCCOWN • Burlington, Vermont Executive Office DAVID HARMON,Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • infoldgeorgewright.org • www.georgewright.org Tfie George Wright Forum REBECCA CONARD & DAVID HARMON, Editors © 2010 The George Wright Society, Inc. -

2017 Experience Planner

2017 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours, and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents LODGING Old Faithful Inn, Old Faithful Lodge Cabins, Old General Info 3 OF Must-Do Adventures 4 Faithful Snow Lodge & Cabins (pg 11-14) Visitor Centers & Park Programs 5 GV Grant Village Lodge (pg. 27-28) Visiting Yellowstone with Kids 6 Canyon Lodge & Cabins (pg 21-22) Tips for Summer Wildlife Viewing 9 CL 12 Awesome Day Hikes 19-20 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel, Lake Lodge Cabins (pg 15-18) Photography Tips 23-24 M Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel & Cabins (pg 7-8) How to Travel Sustainably 29-30 Animals In The Park 33-34 RL Roosevelt Lodge (pg 25-26) Thermal Features 35-36 CAMPING Working in Yellowstone 43-44 (Xanterra-operated Campground) Partner Pages 45-46 Canyon, Madison, Bridge Bay, Winter Fishing Bridge RV Park, Grant Village (pg 31-32) Reasons to Visit in Winter 37-38 Winter Packages 39-40 DINING Winter Tours & Activities 41-42 Old Faithful Inn Dining Room, Bear Paw Deli, OF Obsidian Dining Room, Geyser Grill, Old Faithful Location Guides Lodge Cafeteria (pg 11-14) Grant Village Dining Room, Grant Village Lake House Mammoth Area 7-8 GV Old Faithful Area 11-14 (pg 27-28) Yellowstone Lake Area 15-18 Canyon Lodge Dining Room, Canyon Lodge Canyon Area 21-22 CL Roosevelt Area 25-26 Cafeteria, Canyon Lodge Deli (pg 21-22) Grant Village Area 27-28 Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room, Lake Hotel LK Campground Info 31-32 Deli, Lake Lodge Cafeteria (pg 15-18) Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room, Mammoth M Terrace Grill (pg 7-8) Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room. -

Architecture of Yellowstone a Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L

Architecture of Yellowstone A Microcosm of American Design by Rodd L. Wheaton The idea of Yellowstone lands. The army’s effort be- National Park—the preser- gan from the newly estab- vation of exotic wilderness— lished Camp Sheridan, con- was a noble experiment in structed below Capitol Hill 1872. Preserving nature and at the base of the lower ter- then interpreting it to the park races at Mammoth Hot visitors over the last 125 years Springs. has manifested itself in many Beyond management management strategies. The difficulties, the search for an few employees hired by the architectural style had be- Department of the Interior, gun. The Northern Pacific then the U.S. Army cavalry- Railroad, which spanned men, and, after 1916, the Montana, reached Cinnabar rangers of the National Park with a spur line by Septem- Service needed shelter; ber 1883. The direct result of hence, the need for architec- this event was the introduc- ture. Whether for the pur- tion of new architectural pose of administration, em- styles to Yellowstone Na- ployee housing, mainte- tional Park. The park’s pio- nance, or visitor accommo- neer era faded with the ad- dation, the architecture of vent of the Queen Anne style Yellowstone has proven that that had rapidly reached its construction in the wilder- zenith in Montana mining ness can be as exotic as the The burled logs of Old Faithful’s Lower Hamilton Store epitomize the communities such as Helena landscape itself and as var- Stick style. NPS photo. and Butte. In Yellowstone ied as the whims of those in the style spread throughout charge. -

Lake Guernsey State Park National Historic Landmark Form Size

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Other Name/Site Number: Lake Guernsey Park, Guernsey Lake Park, Guernsey State Park 2. LOCATION Street & Number: One Mile NW of Guernsey, WY Not for publication: City/Town: Guernsey Vicinity: X State: Wyoming County: Platte Code: 031 Zip Code: 82002 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: X Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 14 37 buildings 0 sites 43 9 structures 0 0 objects 60 46 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: Park historic district listed in 1980. resources not enumerated Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Historic Park Landscapes in National and State Parks, 1995 NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 LAKE GUERNSEY STATE PARK Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Yellowstone National Park! Renowned Snowcapped Eagle Peak

YELLOWSTONE THE FIRST NATIONAL PARK THE HISTORY BEHIND YELLOWSTONE Long before herds of tourists and automobiles crisscrossed Yellowstone’s rare landscape, the unique features comprising the region lured in the West’s early inhabitants, explorers, pioneers, and entrepreneurs. Their stories helped fashion Yellowstone into what it is today and initiated the birth of America’s National Park System. Native Americans As early as 10,000 years ago, ancient inhabitants dwelled in northwest Wyoming. These small bands of nomadic hunters wandered the country- side, hunting the massive herds of bison and gath- ering seeds and berries. During their seasonal travels, these predecessors of today’s Native American tribes stumbled upon Yellowstone and its abundant wildlife. Archaeologists have discov- ered domestic utensils, stone tools, and arrow- heads indicating that these ancient peoples were the first humans to discover Yellowstone and its many wonders. As the region’s climate warmed and horses Great Fountain Geyser. NPS Photo by William S. Keller were introduced to American Indian tribes in the 1600s, Native American visits to Yellowstone became more frequent. The Absaroka (Crow) and AMERICA’S FIRST NATIONAL PARK range from as low as 5,314 feet near the north Blackfeet tribes settled in the territory surrounding entrance’s sagebrush flats to 11,358 feet at the Yellowstone and occasionally dispatched hunting Welcome to Yellowstone National Park! Renowned snowcapped Eagle Peak. Perhaps most interesting- parties into Yellowstone’s vast terrain. Possessing throughout the world for its natural wonders, ly, the park rests on a magma layer buried just one no horses and maintaining an isolated nature, the inspiring scenery, and mysterious wild nature, to three miles below the surface while the rest of Shoshone-Bannock Indians are the only Native America’s first national park is nothing less than the Earth lies more than six miles above the first American tribe to have inhabited Yellowstone extraordinary. -

2016 Experience Planner a Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’T Just See Yellowstone

2016 Experience Planner A Guide to Lodging, Camping, Dining, Shopping, Tours and Activities in Yellowstone Don’t just see Yellowstone. Experience it. MAP LEGEND Contents DINING Map 2 OF Old Faithful Inn Dining Room Just For Kids 3 Ranger-Led Programs 3 OF Bear Paw Deli Private Custom Tours 4 OF Obsidian Dining Room Rainy Day Ideas 4 OF Geyser Grill On Your Own 5 Wheelchair Accessible Vehicles 6 OF Old Faithful Lodge Cafeteria Road Construction 6 GV Grant Village Dining Room GV Grant Village Lake House CL Canyon Lodge Dining Room Locations CL Canyon Lodge Cafeteria CL Canyon Lodge Deli Mammoth Area 7-9 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Dining Room Old Faithful Area 10-14 Lake Yellowstone Area 15-18 LK Lake Yellowstone Hotel Deli Canyon Area 19-20 LK Lake Lodge Cafeteria Roosevelt Area 21-22 M Mammoth Hot Springs Dining Room Grant Village Area 23-25 Our Softer Footprint 26 M Mammoth Terrace Grill Campground Info 27-28 RL Roosevelt Lodge Dining Room Animals In The Park 29-30 RL Old West Cookout Thermal Features 31-32 Winter 33 Working in Yellowstone 34 SHOPPING For Camping and Summer Lodging reservations, a $15 non-refundable fee will OF be charged for any changes or cancellations Bear Den Gift Shop that occur 30 days prior to arrival. For OF Old Faithful Inn Gift Shop cancellations made within 2 days of arrival, OF The Shop at Old Faithful Lodge the cancellation fee will remain at an amount GV Grant Village Gift Shop equal to the deposit amount. CL Canyon Lodge Gift Shop (Dates and rates in this Experience Planner LK Lake Hotel Gift Shop are subject to change without notice. -

T:J~ 455 HI~: ~ Ll Lows+One in STORAGE

YELL T:J~ 455 HI~: ~ ll lows+one IN STORAGE HOT SPRING ACTIVITY IN THE GEYSER BASINS OF THE FIREHOLE RIVER FOR THE 1960 SEASON .GEORGE D. MARLER l i.J\SE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFOm.iATION CENTER oru MIC. '"'?~ .. J DENVER SERVICE CEmER NATIONAL PARK• SERVICE Hot Spring Activity In The Geyser Basins Of The Firehole River For The 1960 Season George D. Marler* The hot springs in the geyser basins of the Firehole River continued to show marked effects and alterations due to the Hebgen Lake earthquake of the previous year. In general, the springs which did not return to near pre-quake status within a few days to about 6 weeks following the quake continued during all of 1960 to persist, with modifications, in the changes that had been induced in them. Many alterations in hot spring activity that resulted from the earth quake were latent in character. Days, weeks and sometimes months passed before these changes became evident. Some of the changes in hydrothermal functioning during 1960 must be ascribed to alterations in ground structure produced by the earthquake. These changes resulted in new foci of expression of the thermal energy. In many places deep seated fracturing has so altered former avenues of steam egress that' there is little or no liklihood that conditions in the geyser basins will ever be the same as before the big tremor. There is~ high degree of propability that it will be several years befor~ the hot springs along the Firehole River become what might be called stabilized from the effects of the 1959 ear~hquake. -

OVERCOMING OBSCURITY the Yellowstone Architecture of Robert C

OVERCOMING OBSCURITY The Yellowstone Architecture of Robert C. Reamer Ruth Quinn MONTANA HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY, F.J. HAYNES ARCHITECTURAL DRAWINGS COLLECTION A Reamer drawing of the proposed Canyon Hotel, built in 1910. COURTESY QUINN RUTH “His friends know he appears to be looking down, while he builds looking up.…The effort to impress is not his. He is too busy looking down…creating.” IRST-TIME CALLERS to the Xanterra Central Reservations Offi ce in Yellow- Fstone frequently make their fi rst request a stay at the Old Faithful Inn. They do not always know what to call it; they say “Old Faithful Lodge” more often than not. Yet it is the lodging facility in Yellowstone that everyone seems to know. It may well be the second most famous feature in Yellowstone, after Old Faithful Geyser itself. By contrast, last summer a woman came into the inn looking for the plaque bearing the architect’s name—and, rare among visitors, she already knew it. She was visiting from name a handful. Most of us are aware of his contributions Oberlin, Ohio, the place of Robert Reamer’s birth. Unfortu- to the Old Faithful Inn, the Lake Hotel, the Mammoth Hot nately, she found no such plaque at the Old Faithful Inn. It Springs Hotel, and the demolished Grand Canyon Hotel. is diffi cult to fi nd Reamer’s name anywhere around the park, His name is also well associated with the Executive House at even in the Yellowstone building that has come to be so power- Mammoth. (He has also received credit, in error I believe, for fully linked with him—the building that has for many people the Norris Soldier Station, the Roosevelt Arch, and the Lake come to defi ne what they admiringly, if inaccurately, think of Lodge.) But these well-known projects account for only a part as the “Reamer style.” of the work he did for Yellowstone, work that should arguably Ten years ago, when I fi rst read that Robert Reamer had have made his name among the best-known in the history of designed more than 25 projects for the park, I was astonished the park. -

Dclassification

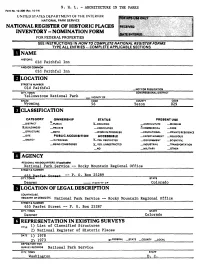

N. H. L. - ARCHITECTURE IN THE PARKS Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENTOFTHE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY » NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS IINAME HISTORIC Old Faithful Inn AND/OR COMMON Old Faithful Inn LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Old Faithful —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Yellows tone National Park VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wyoming 56 Teton 029 DCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED — AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILOING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (H *f>f>tic»bi») National Park Service Rocky Mountain Regional Office STREET & NUMBER p * Q - BQX 25289 CITY. TOWN STATE Denver VICINITY OF Colorado LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC National Park Service Rocky Mountain Regional Office STREET & NUMBER 655 Parfet Street ~ P. 0. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE Denver Colorado REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE 1) List of Classified Structures 2) National Register of Historic Places DATE 1) 1978 2) 1973 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D. C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNAtTE*EO ^.ORIGINALSITE _GOQO —RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE. X-FAIR _UNEXPOSED Qxa Jtaithful Inn is a massive building wl$hj.$o CL short viewing distance of Old Faithful Geyser, the most famous geyser in the United States.