Pre-Prabhas Assemblage from Gujarat, Western India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somnath Travel Guide - Page 1

Somnath Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/somnath page 1 devotion at the Somnath Temple. It finds Max: Min: Rain: 31.79999923 19.79999923 2.20000004768371 mention in the Hindu puranas and the 7060547°C 7060547°C 6mm Somnath Mahabharata. Literally translated as the Apr Home to one of the 12 sacred Shiva "Lord of the Moon," the town and its temple Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. celebrate the most auspicious Karthik Jyotirlinga's in India, the grandeur Max: Min: Rain: 0.0mm Poornima (or full-moon) in the month of 32.09999847 22.79999923 of Somnath is sure to take your 4121094°C 7060547°C November/ December with full fervour and May breath away. The lofty shikharas flavour. The reverberating sounds of Shiv Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen. add colour to the town and flavour bhajans and the legend, culture and Max: Min: Rain: to the lives of people who visit it. tradition surrounding it, will accompany you 32.79999923 26.20000076 4.40000009536743 during your entire stay at Somanth. It has 706055°C 2939453°C 2mm been popularly dubbed as the "shrine Jun eternal," for its ability to stand tall in the Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, umbrella. face of destruction - it's been rebuilt six Famous For : City Max: 32.5°C Min: Rain: times. 27.39999961 134.800003051757 8530273°C 8mm Somnath is famous for its grand Shiva When To Jul temple, one of the 12 revered Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, Jyotirlingas, located right on the shore of the umbrella. Arabian Sea, in Max: Min: Rain: VISIT 30.70000076 26.60000038 269.799987792968 Junagadh District. -

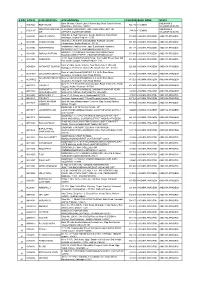

CIN/BCIN Company/Bank Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY)

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 L85195TG1984PLC004507 Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) CIN/BCIN Prefill Company/Bank Name DR.REDDY'S LABORATORIES LTD 27-JUL-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 5729595.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) NEETA NARENDRA SHAH NA NA NA CHANDRIKA APT.,SHINGADA TALAV,W.NO.4016,,NASIKINDIA MAHARASHTRA NASIK DPID-CLID-1201750200019180Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend150.00 30-AUG-2020 ARUN KUMAR RADHAKRISHAN A-40,(60.MEATER),POCKET-00,,SECTOR-2,ROHINI,DELHIINDIA Delhi Delhi FOLIOA00001 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend180.00 30-AUG-2020 AVINASH BALWANT DEV BALWANT 1 JASMIN APARTMENTS,NEW PANDITINDIA COLONY GANGAPURMAHARASHTRA ROAD,NASIK,NASIK NASIK FOLIOA00403 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend60.00 30-AUG-2020 A RAVI KUMAR A KAMESWAR RAO DR. -

A History of Indian Music by the Same Author

68253 > OUP 880 5-8-74 10,000 . OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Call No.' poa U Accession No. Author'P OU H Title H; This bookok should bHeturned on or befoAbefoifc the marked * ^^k^t' below, nfro . ] A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC BY THE SAME AUTHOR On Music : 1. Historical Development of Indian Music (Awarded the Rabindra Prize in 1960). 2. Bharatiya Sangiter Itihasa (Sanglta O Samskriti), Vols. I & II. (Awarded the Stisir Memorial Prize In 1958). 3. Raga O Rupa (Melody and Form), Vols. I & II. 4. Dhrupada-mala (with Notations). 5. Sangite Rabindranath. 6. Sangita-sarasamgraha by Ghanashyama Narahari (edited). 7. Historical Study of Indian Music ( ....in the press). On Philosophy : 1. Philosophy of Progress and Perfection. (A Comparative Study) 2. Philosophy of the World and the Absolute. 3. Abhedananda-darshana. 4. Tirtharenu. Other Books : 1. Mana O Manusha. 2. Sri Durga (An Iconographical Study). 3. Christ the Saviour. u PQ O o VM o Si < |o l "" c 13 o U 'ij 15 1 I "S S 4-> > >-J 3 'C (J o I A HISTORY OF INDIAN MUSIC' b SWAMI PRAJNANANANDA VOLUME ONE ( Ancient Period ) RAMAKRISHNA VEDANTA MATH CALCUTTA : INDIA. Published by Swaxni Adytaanda Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta-6. First Published in May, 1963 All Rights Reserved by Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Calcutta. Printed by Benoy Ratan Sinha at Bharati Printing Works, 141, Vivekananda Road, Calcutta-6. Plates printed by Messrs. Bengal Autotype Co. Private Ltd. Cornwallis Street, Calcutta. DEDICATED TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AND HIS SPIRITUAL BROTHER SWAMI ABHEDANANDA PREFACE Before attempting to write an elaborate history of Indian Music, I had a mind to write a concise one for the students. -

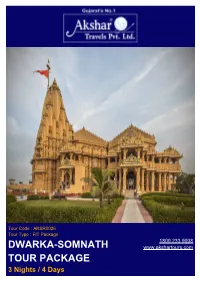

Dwarka-Somnath Tour Package

Tour Code : AKSR0026 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 DWARKA-SOMNATH www.akshartours.com TOUR PACKAGE 3 Nights / 4 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 4Cities 4Days 1Activities Accomodation Meal 02 NIGHTS ACCOMODATION IN DWARKA 03 BREAKFAST 03 DINNER 01 NIGHT ACCOMODATION IN SOMNATH Visa & Taxes Highlights Accommodation on double sharing 5% Gst Extra Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Jamnagar : Lakhota lake , Lakhota museum and Bala hanuman temple. - Dwarka : Bet Dwarka , Nageshwar Jyotirlinga , Rukmani Temple. - Porbandar : Kirti mandir (Gandhiji birth place), Sudama Temple. - Somnath : Somnath jyotirlinga, Triveni sangam, Bhalka tirth. SIGHTSEEINGS JAMNAGAR On an island in the center of the lake stands the circular Lakhota tower, built for drought relief on orders from Jam Ranmalji after the failed monsoons in 1834, 1839 and 1846 made it difficult for the people of the city to find food and resources. Originally designed as a fort such that soldiers posted around it could fend off an invading enemy army with the lake acting as a moat, the tower known as Lakhota Palace now houses the Lakhota Museum. The collection includes artifacts spanning from 9th to 18th century, pottery from medieval villages nearby and the skeleton of a whale. The very first thing you see on entry, however, before the historical and archaeological information, is the guardroom with muskets, swords and powder flasks, reminding you of the structure’s original purpose and proving the martial readiness of the state at the time. The walls of the museum are also covered in frescoes depicting various battles fought by the Jadeja Rajputs. -

(1994) 6 Supreme Court Cases 360 (Before M.N. Venkatachaliah, C.J. and A.M. Ahmadi, J.S. Verma, G.N. Ray, and S.P. Bharucha

(1994) 6 Supreme Court Cases 360 (Before M.N. Venkatachaliah, C.J. And A.M. Ahmadi, J.S. Verma, G.N. Ray, and S.P. Bharucha, JJ.) Transferred Case (C) Nos. 41, 43 and 45 of 1993 Dr. M. Ismail Faruqui and Ors. ..... Petitioners Vs. Union of India and Ors. ..... Respondents With Writ Petition (Civil) No. 208 of 1993 Mohd. Aslam ....... Petitioner Vs. Union of India and others ....., Respondents With Special Reference No. 1 of 1993 with I.A. No. 1 of 1994 in T.C.No. 44 of 1993 Hargyan Singh ..... Petitioner Vs. State of U.P. And Ors. ..... Respondents With Transferred Case (C) No.42 of 1993 Thakur Vijay Ragho Bhagwan Birajman Mandir and Another .... Petitioners Vs. Union of India and Others .... Respondents 1 J. S. VERMA, J. (for Venkatachaliah, C.J., himself and Ray, J)- "We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another." - Jonathan Swift Swami Vivekananda said - "Religion is not in doctrines, in dogmas, nor in intellectual argumentation; it is being and becoming, it is realisation." This thought comes to mind as we contemplate the roots of this controversy. Genesis of this dispute is traceable to erosion of some fundamental values of the plural commitments of our polity. 2. The constitutional validity of the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act, 1993 (No. 33 of 1993) (hereinafter referred to as "Act No. 33 of 1993" or "the Act") and the maintainability of Special Reference No. 1 of 1993 (hereinafter referred to as "the Special Reference") made by the President of India under Art. -

Except Nasik Division Pilgrims, Other Divisions Pilgrims Leave One Day Before for Nasik Division by Available Vehicles

Day1 Except Nasik Division Pilgrims, Other Divisions Pilgrims Leave One Day Before For Nasik Division By Available Vehicles. Day2 In Morning At 08 Am Depart To Tryambak, At Tryambak Darshan Of Tryambakeshwar Jyotirling (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) Then Depart To Verul, At Verul Darshan Of Ghrushneshwar Jyotirling (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) & Stay In Verul/Parali. Day3 In Morning At Parali Darshan Of Vaijyanath Jyotirling (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) Then At Aoundha Darshan Of Nagnath Jyotirling (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) & Then By Night Travel Depart To Omkareshwar. Day4 In Morning At Omkareshwar, Narmada River Darshan, Omkar-Malmaleshwar Jyotirling Darshan(1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) Then At Ujjain Darshan Of Maha-Ankaleshwar Jyotirling(1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) & Stay In Ujjain. Day5 In Morning At 06 Am Depart To Dakorji, At Dakorji Ranchod-Das Temple Darshan & Stay In Dakorji. Day6 In Morning Depart From Dakorji To Somnath & After Reaching Stay In Girnar/Somnath. Day7 In Morning At Somnath Sorati Somnath Jyotirling Darshan (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings) Then At Prabhas Patan Darshan Of Geeta Temple, At Veraval Bhaluka Temple Darshan, At Porbandar Visit Birth Place Of Rashtra-Pitha Mahatma Gandhi, Then At Mul-Dwarka Bhagvan Shri Krushna Temple Darshan & Then Stay In Dwarka. Day8 In Morning Shri Dwarkadhish Temple Darshan (1 Of Saptapuri & 1 Of 4dham) Then At Bet-Dwarka (Okha) Darshan Of Shri Krushna-Sudama Meet Temple, At Nageshwar Darshan Of Nageshwar Jyotirling (1 Of 12 Jyotirlings), Gopi-Talav, Rukhmini Temple Darshan & Then By Night Travel Depart To (Siddhapur) Matrugaya. Day9 In Morning At Matrugaya Bindu-Sarovar Bath (1 Of Panchamaha-Sarovar) & Make (Maatru- Shraddha) Religious Rituals Then Stay In Paali. -

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

Jyotirlinga Darshan Yatra 2020

Om Namah Shivaya Jyotirlinga Darshan Yatra 2020 सौराष्ट्रे सोमनाथं च श्रीशैले मल्ललका셍जुनम्। उज्जल्िनिां महाकालमो敍कारममलेश्वरम्॥ परलिां वैद्यनाथं च डाककनिां भीमश敍करम्। सेतजबनधे तज रामेशं नागेशं दा셁कावने॥ वाराणसिां तज ल्वश्वेशं त्र्ि륍बकं गौतमीतटे। ल्हमालिे तज केदारं घज�मेशं च ल्शवालिे॥ एताल्न 煍िोल्त셍लु敍गाल्न सािं प्रातः पठेन्नरः। सप्त셍नमकृतं पापं समरणेन ल्वन�िल्त॥ Yatra Overview: Jyotirlinga is considered as one of the prime worship spots for the devotees of Lord Shiva. In Hindu Mythology, it is believed that Jyotirlinga means "The Radiant symbol of the Almighty", so it is the resplendent flame of the almighty solidified to make the worship of it simple. There are a total of 64 Jyotirlingas that are well spread around the landscape of India. However, 12 Jyotirlingas are presumed to be very auspicious and highly revered among them. These jyotirlingas are positioned in eight states of India, likes of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamilnadu, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. As per the Hindu mythologies, visiting Jyotirlingas is an important pilgrimage that wades off all the sins and makes the soul sacrosanct and pure. The devotees visiting these Jyotirlingas become chaste, pure and calm. After visiting these Jyotirlingas, devotees turn home with illuminated and enlightened with highest and divine knowledge. It is also believed that wishes are fulfilled after visiting and having Darshan of these sacred Jyotirlingas. Thus, these Jyotirlingas are visited by Lord Shiva's devotees every year in huge numbers. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 28-JUL-2017

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L85195TG1984PLC004507 Prefill Company/Bank Name DR.REDDY'S LABORATORIES LTD Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 28-JUL-2017 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 1412295.50 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) ARUN KUMAR RADHAKRISHAN A-40,(60.MEATER),POCKET-00,,SECTOR-2,ROHINI,DELHIINDIA Delhi Delhi FOLIOA00001 Interest on matured debentures 33.30 23-MAR-2019 BALVEER SINGH BHADOURIA LATE SRIGS BHADO A-905/3,MIG SECTT.A,MAZAR ROAD,INDIRAINDIA NAGAR,,LUCKNOW,UTTAR PRADESH LUCKNOW FOLIOB00217 Interest on matured debentures 199.80 23-MAR-2019 B VSREE KRISHNA MADHUSUDANA RAOB V 101, VIKASINI APTS,2-2-1121/3 & 3A,NEWINDIA NALLAKUNTA,HYDERABADTELANGANA HYDERABAD FOLIOB00594 Interest on matured debentures 55.50 23-MAR-2019 -

Indian Archaeology 1955-56 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1955-56 —A REVIEW EDITED BY A. GHOSH Director General of Archaeology in India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1993 First Edition 1956 Reprint Edition 1993 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 1993 PRICE Rs. 175 Printed at BENGAL OFFSET WORKS, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi 110005 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All the information contained in this annual Review—the third number in the series—is necessarily based on the material received by me from different sources. While the items relating to the Department of Archaeology, Government of India, were supplied by my colleagues in the Department, to whom my thanks are due, the remain- ing ones, considerable in number and value, were obtained from others who are officially connected with the archaeological activities in the country, viz. the directors of explorations and excavations, the heads of the archaeological organizations in the States where they exist and the chiefs of the leading museums. I am immensely grate- ful to them for having readily sent their reports and, in many cases, illustrations for in- clusion in the Review. In almost all such cases, the sources of the material are obvious, and have not been individually acknowledged. I am also deeply obliged to those colleagues of mine who have helped me in the preparation of the text and plates and have seen the publication through the press within a remarkably short time. The 22nd August I956 A. GHOSH CONTENTS PAGE 1. General ... ... ... ... ... … ... 1 2. Explorations and excavations ... ... ... ... ... 4 3. Epigraphy ... … ... ... ... ... 2.9 4. Preservation of monuments .. -

Shri Mahaprabhuji's 84 Baithakji: 1. Shri Govindghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Govind Ghat, Gokul

Shri Mahaprabhuji's 84 Baithakji: 1. Shri Govindghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Govind Ghat, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:Sureshbhai Mukhiyaji M: 093587 061 76, Amitbhai Mukhiyaji M: 096756 135 32 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura to Gokul 12 Km.) 2. Shri Badi Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Thakrani Ghat, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:M: 097580 97 493 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 3. Shri Shaichya Mandir Baithakji Baithak Address:Shaiya Mandir, Shri Dwarkadhish na Mandirma, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:M: 097192 817 52, M: 097580 974 93 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 4.Shri Vrundavan Bansivat Baithakji Baithak Address:Bansibat, Post Vrindaban - 281121, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Vrindaban Contact Person & Phone:Purushotam Mukhiyaji M: 098979 793 26, 097604 498 47 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 15 Km.) 5. Shri Vishram Ghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Vishram Ghat, Mathura - 281001, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Mathura Contact Person & Phone:Shri Vasantbhai Mukhiyaji M: 098370 166 42 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 6. Shri Madhuvan Baithakji Baithak Address: AT Post Madhuvan - 281141, Maholi, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - MadhubanContact Person & Phone:Shri Jankiben M: 093199 912 31 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 10 Km.) 7. Shri Kumudvan Baithakji Baithak Address:AT Post Kumudvan, Post Usfar (uspar or same par) - 281004, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Kumudvan Contact Person & Phone:-- Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 20 Km.) 8. Shri Bahulavan Baithakji Baithak Address:Shri Bahulavan, Post Bati (Bati Gaon) - 281004 , Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. -

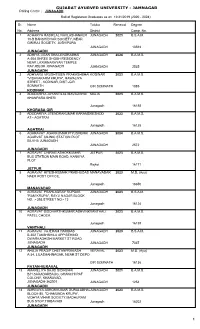

JAMNAGAR Polling Centre : JUNAGADH Roll of Registered Graduates As on 12/31/2019 (2020 - 2024)

GUJARAT AYURVED UNIVERSITY - JAMNAGAR Polling Centre : JUNAGADH Roll of Registered Graduates as on 12/31/2019 (2020 - 2024) Sr. Name Taluka Renewal Degree No. Address District Comp. No. 1 ACHARYA RASIKLAL NAVLASHANKER JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. 10-B BANSHIDHAR SOCIETY, NEAR GIRIRAJ SOCIETY, JOSHIPURA JUNAGADH 10593 JUNAGADH 2 ADHIYA JIGAR SHAILENDRABHAI JUNAGADH 2024 B.A.M.S. A-204 SHREE SHOBH RESIDENCY NEAR LAXMINARAYAN TEMPLE RAYJIBLOK JUNAGADH JUANGADH 2535 JUNAGADH 3 ADHYARU VRUSHTIBEN PRAKASHBHAI KODINAR 2023 B.A.M.S. "VISHVAKARM KRUPA", RAWALIYA STREET , KODINAR, DIST:-GIR SOMNATH GIR SOMNATH 1885 KODINAR 4 ADODARIYA JAYANTILAL MAVAJIBHAI MALIA 2023 B.A.M.S. KHANPARA SHERI Junagadh 16188 KHORASA GIR 5 ADODARIYA JITENDRAKUMAR KARAMSHIBHAIKESHOD 2023 B.A.M.S. AT:- AGATRAI Junagadh 16128 AGATRAI 6 AGARAVAT JIGARKUMAR PIYUSHBHAI JUNAGADH 2024 B.A.M.S. AGARVAT CILINIC STATION PLOT BILKHA JUNAGADH JUNAGADH 2572 JUNAGADH 7 AGRAVAT CHIRAG ASHOKKUMAR JETPUR 2023 B.A.M.S. BUS STATION MAIN ROAD, KANKIYA PLOT Rajkot 16171 JETPUR 8 AGRAVAT HITESHKUMAR PRABHUDAS MANAVADAR 2023 M.D. (Ayu) NAER POST OFFICE, Junagadh 16650 MANAVADAR 9 AGRAVAT PRAHLADRAY RUPDAS JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. "RAM KRUPA", RAYJI NAGAR BLOCK NO. :- 393,STREET NO:- 13 Junagadh 16124 JUNAGADH 10 AGRAVAT SIDDHARTHKUMAR ASHVINKUMARVANTHALI 2023 B.A.M.S. PATEL CHOCK Junagadh 16138 VANTHALI 11 AGRAVAT VAJERAM HARIDAS JUNAGADH 2023 B.S.A.M. B-302 TAKSHSHILA APP BEHIND DWARKADHISH MARKET ST ROAD JUNAGADH JUNAGADH 7037 JUNAGADH 12 AHUJA PRADIP CHETANPRAKASH VERAVAL 2023 M.D. (Ayu) A-34, LILASHAHNAGAR, NEAR ST DEPO GIR SOMNATH 16136 PATAN-VERAVAL 13 AMARELIYA SAJID SIDIKBHAI JUNAGADH 2021 B.A.M.S.