1 Private Herbert Smith Peters, Number 540083 Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Department of Militia and Defence Canada for the Fiscal

The documents you are viewing were produced and/or compiled by the Department of National Defence for the purpose of providing Canadians with direct access to information about the programs and services offered by the Government of Canada. These documents are covered by the provisions of the Copyright Act, by Canadian laws, policies, regulations and international agreements. Such provisions serve to identify the information source and, in specific instances, to prohibit reproduction of materials without written permission. Les documents que vous consultez ont été produits ou rassemblés par le ministère de la Défense nationale pour fournir aux Canadiens et aux Canadiennes un accès direct à l'information sur les programmes et les services offerts par le gouvernement du Canada. Ces documents sont protégés par les dispositions de la Loi sur le droit d'auteur, ainsi que par celles de lois, de politiques et de règlements canadiens et d’accords internationaux. Ces dispositions permettent d'identifier la source de l'information et, dans certains cas, d'interdire la reproduction de documents sans permission écrite. u~ ~00 I"'.?../ 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 > t-i REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MILITIA AND DEFENCE CANADA FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDING MARCH 31 1921 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT H.Q. 650-5-21 100-11-21 OTTAWA F. A. ACLAND PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY 1921 [No. 36-1922] 12 GEORGE V SESSIONAL PAPER No. 36 A. 1922 To General His Excellency the Right HQnourable Lord Byng of Vimy, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., M.V.0., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. -

Recueil Des Actes Administratifs

PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS RECUEIL DES ACTES ADMINISTRATIFS RECUEIL n° 23 du 5 avril 2019 Le Recueil des Actes Administratifs sous sa forme intégrale est consultable en Préfecture, dans les Sous-Préfectures, ainsi que sur le site Internet de la Préfecture (www.pas-de-calais.gouv.fr) rue Ferdinand BUISSON - 62020 ARRAS CEDEX 9 tél. 03.21.21.20.00 fax 03.21.55.30.30 PREFECTURE DU PAS-DE-CALAIS.......................................................................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur communale, départementale et régionale..........................................3 - Arrêté préfectoral accordant la médaille d’honneur agricole............................................................................................53 MINISTERE DE LA JUSTICE-DIRECTION INTERREGIONALE DES SERVICES PENITENTIAIRES...................................................................................................................61 Maison d’arrêt d’Arras........................................................................................................................................................61 Décision du 2 avril 2019 portant délégation de signature...................................................................................................61 DIRECCTE HAUTS-DE-FRANCE..........................................................................................62 - Modifications apportées à la décision du 30 novembre 2018 portant affectation des agents de contrôle dans les unités de contrôle et organisation -

LOZINGHEM - Mariages -- Travaux De Mme Edith Josset - 2014

LOZINGHEM - Mariages -- Travaux de Mme Edith Josset - 2014 AD62 Vue Jr. An EPOUX Notes EPOUSE Notes Miicrofilm Mois Lozinghem-114 7.9 1745 BAILLY veuf POHIER Marie Antoinette / CARDON Jacques Marie Angélique frère Antoine Joseph o vers 1704 o Vers Allouagne (non) + 13.9.1774Lozinghem Lozinghem-73 5.5 1761 BAILLY Jacques DAVE Pierre Joseph + Jean Baptiste 23 ans (signe) POHIER Marie Antoinette Marie Alexandrine 26 ans BAUDELLE Marie Madeleine o 4.4.1738 Lozinghem Cousines germaines LEMIEN o 7.12.1735 Burbure beau frère Guislain Joseph Marie Joseph x Hilarion Joseph veuve CARPENTIER Valentin BROGNIART WILLERETZ et Marie Jeanne DUBOUT X Jean Robert HERMAN Lozinghem-120 22.2 1770 BAILLY Jacques DELIGNY Philippe Jacques Joseph POHIER Marie Antoinette + Marie Louise 30 ans DENISSEL Marie Catherine + 30 ans (signe) frère Jean Baptiste o 30.10.1740 Lozinghem cousin germain Jean Marie o 28.1.1740 Lozinghem + 7.1.1774 Lozinghem DENISSEL veuve POIRIER Albert Lozinghem-50 11.2 1734 BAILLY POHIER Jean Baptiste Jacques Marie Antoinette (signe) o Vers 1701 Lozinghem + 11.7.1741 Lozinghem Lozinghem-19 18.12 1749 BARBIER veuf Marguerite BOULANGER BERROYER Antoine André Marie Jeanne Rose TELIER Marie Joseph + DE Choques o 26.2.1726 Lozinghem frère Alexis Lozinghem-46 12.1 1723 BECU BERROYER Guislain Marie Jacqueline témoins Antoine et Maximilien BERROYER Lozinghem-82 7.2 1741 BECU DENISSEL veuve Antoine Marie Guilaine o Vers 1699 o Vers 1704 + 11.4.1763 Lozinghem + 10.9.1772 Lozinghem Lozinghem-209 5.6 1787 BECU Antoine + DUHAMEL Maximilien Antoine DENISSEL -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

Information Eau Potable Pour Des Demandes Techniques : Pour Des

Information eau potable Retrouvez ci-dessous des précisions quant au mode de fonctionnement du service eau potable pour les abonnés dont la gestion de l’eau potable est encadrée par la régie de l’Agglomération Béthune-Bruay (communes concernées : Annequin, Allouagne, Beuvry, Annezin, Busnes, Auchy-au-Bois, Calonne-Sur-La-Lys, Béthune, Cambrin, Bourecq, Cuinchy, Caucourt, Essars, Chocques, Festubert, Diéval, Givenchy-Lès-La Bassée, Drouvin-Le-Marais, Gonnehem, Ecquedecques, Hinges, Fouquereuil, La Couture, Fouquières-Les-Béthune, Labourse, Gauchin-Le- Gal, Locon, Hermin, Lorgies, Hesdigneul-Lès-Béthune, Mont-Bernanchon, Labeuvrière, Neuve- Chapelle, Lespesses, Richebourg, Lières, Robecq, Ligny-Lès-Aire, Sailly-Labourse, Lozinghem, Saint- Floris, Oblinghem , Vieille-Chapelle, Rebreuve-Ranchicourt, Violaines, Rely, Saint-Hilaire-Cottes, Vaudricourt, Vendin-Lez-Béthune, Verquigneul, Verquin, Westrehem) : Pour des demandes techniques : • Le centre technique de Violaines vous accueille à nouveau de 9h à 12h et de 13h30 à 17h, du lundi au vendredi. (57 rue d'ouvert,62138 Violaines) • Pour toutes démarches techniques (y compris urgences), vous pouvez joindre le 0 800 100 109, • Pour toutes les demandes techniques non urgentes (ex : maintenance ou fuite mineure n’entrainant pas de risques particuliers,…) nous vous invitons à adresser votre demande par mail à [email protected] ou via notre formulaire en ligne sur le site internet dédié : eau.bethunebruay.fr • Les travaux de réseau et la relève des compteurs ont repris dans le respect des règles de distanciation et des gestes barrières. Pour des demandes liées à la facturation : • Le service facturation vous accueille à nouveau à l’hôtel communautaire de Béthune (100 avenue de Londres) exclusivement le matin de 8h30 à 12h, du lundi au vendredi. -

Cahier Des Charges De La Garde Ambulanciere

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE LA GARDE AMBULANCIERE DEPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME Document de travail SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ............................................................................................................................. 2 ARTICLE 1 : LES PRINCIPES DE LA GARDE ......................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2 : LA SECTORISATION ........................................................................................... 4 2.1. Les secteurs de garde ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Les lignes de garde affectées aux secteurs de garde .................................................... 4 2.3. Les locaux de garde ........................................................................................................ 5 ARTICLE 3 : L’ORGANISATION DE LA GARDE ...................................................................... 5 3.1. Elaboration du tableau de garde semestriel ................................................................... 5 3.2. Principe de permutation de garde ................................................................................... 6 3.3. Recours à la garde d’un autre secteur ............................................................................ 6 ARTICLE 4 : LES VEHICULES AFFECTES A LA GARDE....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 5 : L'EQUIPAGE AMBULANCIER ............................................................................. 7 5.1 L’équipage ....................................................................................................................... -

2097-3 EPCI Département De La Somme A2 Au 1Er Septembre 2020

CA DE BETHUNE-BRUAY, CA DE LENS - LIEVIN Les Etablissements Publics de Coopération Intercommunale ARTOIS LYS ROMANE Établissement public de coopération intercommunale dans le département de la Somme (80) (EPCI au 1er septembreCA D'HENIN-CARVIN 2020) CA DES DEUX BAIES CA DU DOUAISIS (CAD) EN MONTREUILLOIS (CA2BM) Communauté Urbaine Fort-Mahon- Plage CC DES 7 VALLEES Nampont Argoules Dominois Quend Villers- Communauté d’Agglomération sur-Authie Vron Ponches- Estruval Vercourt Vironchaux Regnière- Ligescourt Communauté de Communes Écluse Dompierre- Saint-Quentin- Rue Arry en-Tourmont Machy sur-Authie Machiel Bernay-en-Ponthieu Le Boisle Estrées- Bouers lès-Crécy CC DU TERNOIS Vitz-sur-Authie Le Crotoy Forest-Montiers Crécy-en-Ponthieu CC DES CAMPAGNES DE L'ARTOIS Favières Fontaine-sur-Maye Gueschart CC PONTHIEU-MARQUENTERRE Brailly- Neuilly-le-Dien Froyelles Cornehotte CU D'ARRAS Ponthoile Nouvion Noyelles- Maison- Brévillers Forest- Domvast en-Chaussée Ponthieu Frohen- Neuvillette CC OSARTIS MARQUION l'Abbaye Remaisnil Hiermont Maizicourt sur-Authie Bouquemaison Humbercourt Béalcourt Barly Lucheux Noyelles-sur-Mer Bernâtre Le Titre Lamotte- Yvrench St-Acheul Buleux Canchy Mézerolles Cayeux- Saint-Valery- Sailly- Agenvillers Yvrencheux Montigny- Grouches- sur-Mer sur-Somme Flibeaucourt Conteville les-Jongleurs Gapennes Occoches Luchuel Hautvillers- Agenville Ouville Neuilly-l'Hôpital Le Meillard Pendé Outrebois Boismont Heuzecourt Doullens Lanchères Estrébœuf Port-le-Grand Buigny- Millencourt- Cramont Prouville Hem- St-Maclou en-Ponthieu -

Department of Militia and Defence for the Dominion of Canada Report For

The documents you are viewing were produced and/or compiled by the Department of National Defence for the purpose of providing Canadians with direct access to information about the programs and services offered by the Government of Canada. These documents are covered by the provisions of the Copyright Act, by Canadian laws, policies, regulations and international agreements. Such provisions serve to identify the information source and, in specific instances, to prohibit reproduction of materials without written permission. Les documents que vous consultez ont été produits ou rassemblés par le ministère de la Défense nationale pour fournir aux Canadiens et aux Canadiennes un accès direct à l'information sur les programmes et les services offerts par le gouvernement du Canada. Ces documents sont protégés par les dispositions de la Loi sur le droit d'auteur, ainsi que par celles de lois, de politiques et de règlements canadiens et d’accords internationaux. Ces dispositions permettent d'identifier la source de l'information et, dans certains cas, d'interdire la reproduction de documents sans permission écrite. 3-4 EDWARD VI I. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 35 A. 1904 OP MILITIA AND DEFENCE FOR THE DOMINION OF CANADA REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31 1.903 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT OTTAWA PRINTED BY S. E. DA WSO T' PRINTER TO THE KING'S ::\10~T EXCELLE-'- T M.AJES'l'Y 1904 .._TQ, 35-1904,] 3-4 EDWARD VII. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 35 A. 1904 To His Excellency the Right Honourable Sir Gilbert John Elliot, Ea1·l of Minto and Viscount Melgund of lJfelgund, County of F01far, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, Baron Minto of ilfinto, County of Roxburgh, in the Peerage oj Great Britain, one of His Jfajesty's .Jfost Honoumble Privy Uouncil, Baronet oj Nova Scotia, Knight Grand Cross of the Most Di:,tinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint Ge01·ge, &c., Governor General of Canada. -

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (Bassin-Versant De L’Authie Dans Le Département De La Somme)

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (bassin-versant de l’Authie dans le département de la Somme) ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 LOUVENCOURT 80493 AGENVILLE 80005 LUCHEUX 80495 ARGOULES 80025 MAISON-PONTHIEU 80501 ARQUEVES 80028 MAIZICOURT 80503 AUTHEUX 80042 MARIEUX 80514 AUTHIE 80043 MEZEROLLES 80544 AUTHIEULE 80044 MONTIGNY-LES-JONGLEURS 80563 BARLY 80055 NAMPONT-SAINT-MARTIN 80580 BAYENCOURT 80057 NEUILLY-LE-DIEN 80589 BEALCOURT 80060 NEUVILLETTE 80596 BEAUQUESNE 80070 OCCOCHES 80602 BEAUVAL 80071 OUTREBOIS 80614 BERNATRE 80085 PONCHES-ESTRUVAL 80631 BERNAVILLE 80086 PROUVILLE 80642 BERTRANCOURT 80095 PUCHEVILLERS 80645 BOISBERGUES 80108 QUEND 80649 BOUFFLERS 80118 RAINCHEVAL 80659 BOUQUEMAISON 80122 REMAISNIL 80666 BREVILLERS 80140 SAINT-ACHEUL 80697 BUS-LES-ARTOIS 80153 SAINT-LEGER-LES-AUTHIE 80705 CANDAS 80168 TERRAMESNIL 80749 COIGNEUX 80201 THIEVRES 80756 COLINCAMPS 80203 VAUCHELLES-LES-AUTHIE 80777 CONTEVILLE 80208 VERCOURT 80787 COURCELLES-AU-BOIS 80217 VILLERS-SUR-AUTHIE 80806 DOMINOIS 80244 VIRONCHAUX 80808 DOMLEGER-LONGVILLERS 80245 VITZ-SUR-AUTHIE 80810 DOMPIERRE-SUR-AUTHIE 80248 VRON 80815 DOULLENS 80253 ESTREES-LES-CRECY 80290 FIENVILLERS 80310 FORT-MAHON-PLAGE 80333 FROHEN-SUR-AUTHIE 80369 GEZAINCOURT 80377 GROUCHES-LUCHUEL 80392 GUESCHART 80396 HEM-HARDINVAL 80427 HEUZECOURT 80439 HIERMONT 80440 HUMBERCOURT 80445 LE BOISLE 80109 LE MEILLARD 80526 LEALVILLERS 80470 LIGESCOURT 80477 LONGUEVILLETTE 80491 Secteur 2 : MAYE (bassin-versant de la Maye) ARRY 80030 BERNAY-EN-PONTHIEU -

Les Élus De La CCI Artois - MANDATURE 2017-2021 - 60 Élus

les élus de la CCI Artois - MANDATURE 2017-2021 - 60 élus - L’assemblée de la CCI Artois se compose de 60 élus, dont 10 sont membres du Bureau et 15 siègent à la CCI de région Hauts-de-France Elu CCI de région Hauts-de-France LES MEMBRES DU BUREAU COMMERCE Catégorie C1 - 0 à 4 salariés DÉMISSIONNAIRE Martine BAIL Carol BLEITRACH Jérôme DIEVAL Laurence DUBRULLE Jean-Marc DEVISE Fabienne FRANÇOIS BLANC NACRE SARL CTB PHOTO JEAN PHARMACIE DES Président Vice-présidente Aubigny-en-Artois Lens Arras GRANDES PRAIRIES UNIJECT services Sainte-Catherine Bapaume HELFY Mazingarbe Pascale LOUCHART Laurent MORET Jean-Paul PIPON PUPUCE OPTIQUE DU BEFFROI SARL REGARDS Bruno ROSIK Alain CUISSE Izel-les-Hameaux Arras Aubigny-en-Artois Vice-président commerce Vice-président LES JARDINS DE Béthune L’ARCADIE PIREP Lens Busnes Catégorie C2 - 5 salariés et + DÉMISSIONNAIRE DÉMISSIONNAIRE DÉMISSIONNAIRE Patrick LELEU Pascal PAWLACZYK Vice-président Lens Trésorier TRANSPORTS JULES SARL EGP SAUDEMONT Ludwig BOISNARD Bénédicte CALLENS Philippe CARDON Romuald CONDAMINE BENOIT Saint-Laurent-Blangy AUCHAN INTERMARCHE ESPRIT PORTE NORD INTERMARCHE Lens Arras Lambres Bruay-la-Buissière Noyelles-sous-Lens Florence THEVENIN Johann MENET er Murielle CORNOLLE Véronique DAMIENS François DESCLOQUEMANT Francis DUMARQUEZ Trésorière adjointe 1 secrétaire PHARMACIE CORNOLLE NORD PESAGE LE SAINT-GERMAIN ARTOIS BURO CONCEPT CLARISME FINANCES SAS TP PLUS Arras Annequin Arras Fresnes-les-Montauban Béthune Billy-Berclau DÉMISSIONNAIRE Annick CASTELAIN Dany EMONTSGAST Jacques FLOTAT -

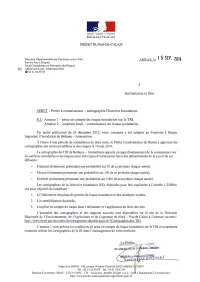

ARRAS Le F 5 SEP, 2014

Liberré • Egalité • Fraternité •RÉPUBLI QUE FRANÇAISE PRÉFET DU PAS-DE-CALAIS Direction Dépa rtementale des Tenitoires et de la Mer ARRAS , le f 5 SEP, 2014 Service Eau et Risques Unité Connaissance et Prévention des Risques セ@ Affaire suivie par : Emmanuel Duée w 03.2 1.22.99. 78 à destinataires in fine OBJET : Porter à connaissance - cartographie Directive Inondation. P.J.: Annexe 1 - prise en compte du risque inondation sur le TRI. Annexe 2 - contexte local - connaissance du risque inondation. Par arrêté préfectoral du 26 décembre 201 2, votre commune a été intégrée au Territoire à Risque Important d'inondation de Béthune - Armentières. À l' issue d'une période de consultation de deux mois, le Préfet Coordonnateur de Bassin a approuvé les cartographies des zones inondables et des risques le 16 mai 2014. La cartographie du TRI de Béthune - Armentières apporte un approfondissement de la connaissance sur les surfaces inondables et les risques pour trois types d'événements liés à des débordements de la Lys et de ses affluents : Fréquent (événement présentant une probabilité sur 10 de se produire chaque année). Moyen (événement présentant une probabilité sur 100 de se produire chaque année). Extrême (événement présentant une probabilité sur 1000 de se produire chaque année). Les cartographies de la Directive Inondation (DI), élaborées pour être exploitées à l'échelle l/25000e, ont pour obj ectifs de contribuer : 1. à l'élaboration des plans de gestion du risque inondation et des stratégies locales, 2. à la sensibilisation du public, 3. à la prise en compte du risque dans l'urbanisme et l'application du droit des sols. -

Guide to Canadian Sources Related to Southern Revolutionary War

Research Project for Southern Revolutionary War National Parks National Parks Service Solicitation Number: 500010388 GUIDE TO CANADIAN SOURCES RELATED TO SOUTHERN REVOLUTIONARY WAR NATIONAL PARKS by Donald E. Graves Ensign Heritage Consulting PO Box 282 Carleton Place, Ontario Canada, K7C 3P4 in conjunction with REEP INC. PO Box 2524 Leesburg, VA 20177 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1: INTRODUCTION AND GUIDE TO CONTENTS OF STUDY 1A: Object of Study 1 1B: Summary of Survey of Relevant Primary Sources in Canada 1 1C: Expanding the Scope of the Study 3 1D: Criteria for the Inclusion of Material 3 1E: Special Interest Groups (1): The Southern Loyalists 4 1F: Special Interest Groups (2): Native Americans 7 1G: Special Interest Groups (3): African-American Loyalists 7 1H: Special Interest Groups (4): Women Loyalists 8 1I: Military Units that Fought in the South 9 1J: A Guide to the Component Parts of this Study 9 PART 2: SURVEY OF ARCHIVAL SOURCES IN CANADA Introduction 11 Ontario Queen's University Archives, Kingston 11 University of Western Ontario, London 11 National Archives of Canada, Ottawa 11 National Library of Canada, Ottawa 27 Archives of Ontario, Toronto 28 Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library 29 Quebec Archives Nationales de Quebec, Montreal 30 McCord Museum / McGill University Archives, Montreal 30 Archives de l'Universite de Montreal 30 New Brunswick 32 Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton 32 Harriet Irving Memorial Library, Fredericton 32 University of New Brunswick Archives, Fredericton 32 New Brunswick Museum Archives,