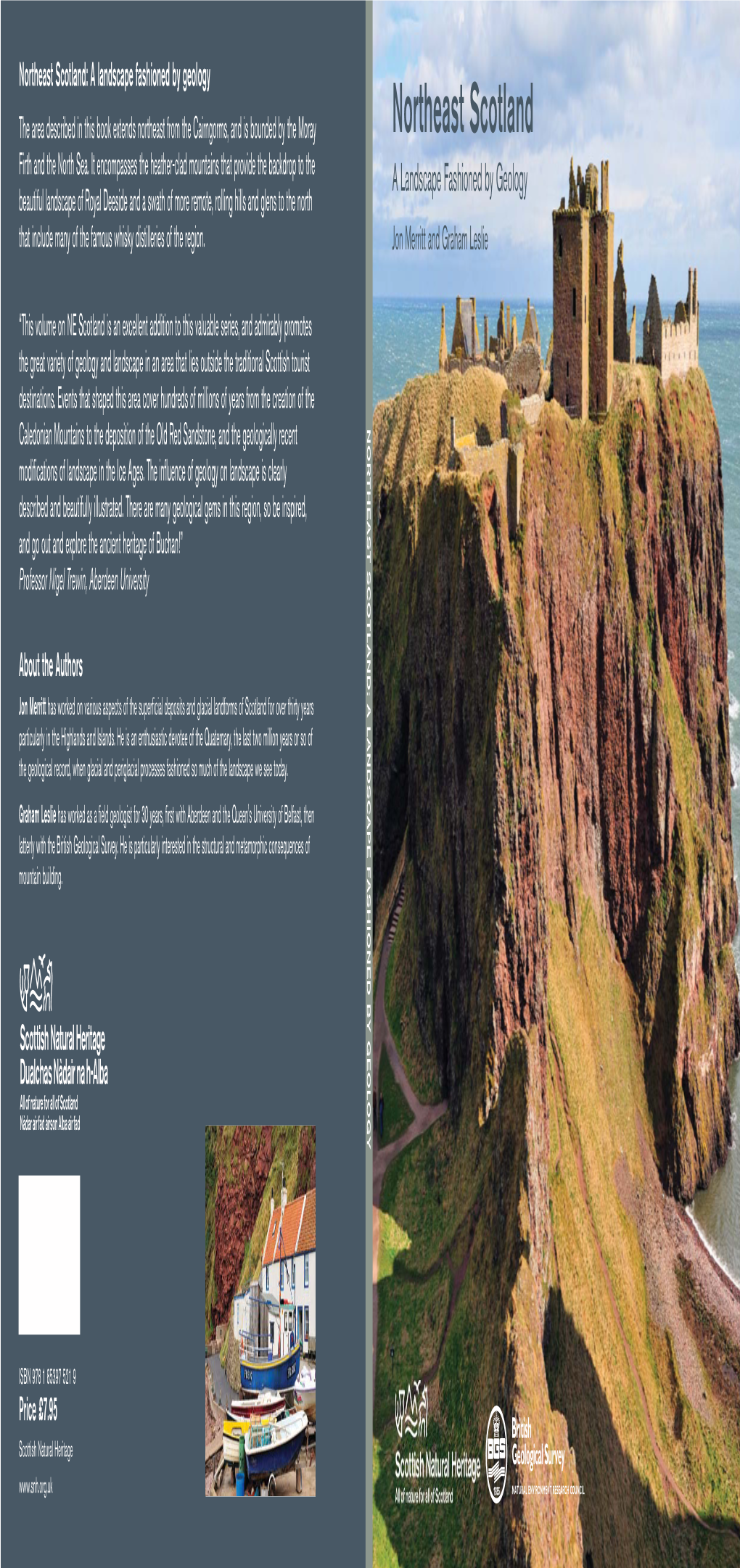

A Landscape Fashioned by Geology Jon Merritt and Graham Leslie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hillforts of Strathdon: 2004-2010

The Hillforts of Strathdon: 2004-2010 Murray Cook Having worked across Scotland and Northern England for the last 15 years I can say without hesitation that projects with Ian in Aberdeenshire always filled me with joy and renewed passion and enthusiasm for archaeology: without him this project would not have taken place. Introduction In ‘ In the Shadow of Bennachie’ the RCAHMS survey of the Strathdon area, the hillforts (throughout the paper ‘hillfort’ is used as shorthand to describe an enclosure whether on a hill or not) of the area were classified into a six-fold scheme, according to size and defensive system recorded (RCAHMS 2007, 100-1). Of course, the information was gathered through non-invasive survey, and it is unclear how these classes related to each other, as their dates were unknown. Using the same criteria of size and defensive system, albeit with a larger data set Ralston ( et al 1983) proposed a different classification as did Feachem a generation earlier (1966). These conflicting classifications illustrate the essentially limited value of such attempts: without hard data they remain talking points to be reinterpreted once a generation. In order to further the debate - hard dating evidence from physical excavation is needed. In what some have described as naïve, The Hillforts of Strathdon Project was set up in an attempt to characterise and date the type-sites of the area, through a programme of key- hole excavation on the variety of enclosures in the area. After six seasons of excavations on nine enclosures with local volunteers and students, this paper briefly summarises the key results in chronological order and the general conclusions. -

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 Km Alford

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Alford-Haughton Country Park Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This is an easy circular walk with modest overall ascent. Starting and finishing at Alford, an attractive Donside village situated in its own wide and fertile Howe (or Vale), the route passes though parkland, woodland, riverside and farming country, with extensive rural views. Duration: 2.5 hours Route Overview Duration: 2.5 hours. Transport/Parking: Frequent Stagecoach #248 service from Aberdeen. Check timetable. Parking spaces at start/end of walk outside Alford Valley Railway, or nearby. Length: 7.570 km / 4.73 mi Height Gain: 93 meter Height Loss: 93 meter Max Height: 186 meter Min Height: 131 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly on good paths and paved surfaces. A fair amount of walking on pavements and quiet minor roads. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance. Difficulty: Easy. Dog Friendly: Yes, but keep dogs on lead near to livestock, and on public roads. Refreshments: Options in Alford. Description This is a gentle ramble around and about the attractive large village of Alford, taking in the pleasant environs of Haughton Country Park, a section along the banks of the River Don, and the Murray Park mixed woodland, before circling around to descend into the centre again from woodland above the Dry Ski Slope. Alford lies within the Vale of Alford, tracing the middle reaches of the River Don. In the summer season, the Alford Valley (Narrow-Gauge) Railway, Grampian Transport Museum, Alford Heritage Centre and Craigievar Castle are popular attractions to visit when in the area. -

Catterline School

Catterline School Handbook 2020/21 2 | Contents Introduction to Catterline School 4 Our Vision, Values and School Ethos 7 Curriculum 9 Assessment and Reporting 14 Transitions (Moving On) 16 1 Admissions 17 2 Placing Requests & School Zones 17 Support for Children and Young People 18 3 Getting it Right for Every Child 18 4 Wellbeing 18 5 Children’s Rights 19 6 The Named Person 20 7 Educational Psychology 20 8 Enhanced Provision & Community Resource Hubs 21 9 Support for Learning 21 10 The Child’s Plan 22 11 Child Protection 23 12 Further Information on Support for Children and Young People 23 Parent & Carer Involvement and Engagement 24 13 Parental Engagement 24 14 Communication 24 15 ParentsPortal.scot 25 16 Learning at Home 25 17 Parent Forum and Parent Group 26 18 Parents and School Improvement 26 19 Volunteering in School 26 20 Collaborating with the Community 26 21 Addressing Concerns & Complaints 26 School Policies and Useful Information 28 22 Attendance 28 23 Holidays during Term Time 29 24 Dress Code 30 | 3 25 Clothing Grants 30 26 Transport 31 27 Privilege Transport 31 28 Early Learning & Childcare Transport 32 29 Special Schools and Enhanced Provision 32 30 School Closure & Other Emergencies 32 31 Storm Addresses 33 32 Change of address and Parental Contact Details 34 33 Anti-bullying Guidance 34 34 School Meals 35 35 Healthcare & Medical 36 36 Schools and Childcare – Coronavirus 38 37 Exclusion 38 38 Educational Visits 38 39 Instrumental Tuition 38 40 Public Liability Insurance 39 41 School Off-Site Excursion Insurance 39 42 Data We Hold and What We Do With It. -

Education & Children's Services Proposal

Education and Children’s Services EDUCATION & CHILDREN’S SERVICES PROPOSAL DOCUMENT: AUGUST 2015 ABERDEENSHIRE SCHOOLS ENHANCED PROVISION A) THE RELOCATION OF NEWTONHILL SCHOOL ENHANCED PROVISION CENTRE TO PORTLETHEN SCHOOL, PORTLETHEN AND B) THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN ENHANCED PROVISION CENTRE AT MILL O’ FOREST SCHOOL, STONEHAVEN 1 Proposal for Statutory Consultation A) THE RELOCATION OF NEWTONHILL SCHOOL ENHANCED PROVISION CENTRE TO PORTLETHEN SCHOOL, PORTLETHEN AND B) THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AN ENHANCED PROVISION CENTRE AT MILL O’ FOREST SCHOOL, STONEHAVEN SUMMARY PROPOSAL Enhanced provision across Aberdeenshire has been reviewed and a nine area model is currently being implemented during 2014-16. (See pages 9-11 Section 4 Educational Benefits Statement 4.6.1 – 4.6.4) Each cluster will have a primary and a secondary Enhanced Provision Centre and each Area will have a Community Resource Hub. The aim is to provide support for all learners in the local schools through universal and targeted support and to ensure that Enhanced Provision is located where the need is greatest. At present the Enhanced Provision Centre for the Portlethen and Stonehaven cluster is located at Newtonhill School, Newtonhill. It is proposed that the primary Enhanced Provision Centre at Newtonhill will be relocated to Portlethen Primary School where the need is greatest. The only remaining cluster without primary Enhanced Provision is Stonehaven and the proposal is to develop a new primary Enhanced Provision Centre at Mill O’ Forest School, Stonehaven. The new Enhanced Provision model aims to increase capacity at a school and cluster level for all learners to ensure greater consistency of, and equity of access to, an improved quality of provision across the authority. -

Governor Island MARINE RESERVE

VISITING RESERVES Governor Island MARINE RESERVE Governor Island Marine Reserve, with its spectacular underwater scenery, is recognised as one of the best temperate diving locations in Australia. The marine reserve includes Governor Island and all waters and other islands within a 400m diameter semi-circle from the eastern shoreline of Governor Island (refer map). The entire marine reserve is a fully protected ‘no-take’ area. Fishing and other extractive activities are prohibited. Yellow zoanthids adorn granite boulder walls in the marine reserve. These flower-like animals use their tentacles to catch tiny food particles drifting past in the current. Getting there Photo: Karen Gowlett-Holmes Governor Island lies just off Bicheno – a small fishing and resort town on Tasmania’s east coast. It is located Things to do about two and a half hours drive from either Hobart or The reserve is a popular diving location with Launceston. over 35 recognised dive sites, including: Governor Island is separated from the mainland by a The Hairy Wall – a granite cliff-face plunging to 35m, narrow stretch of water, approximately 50m wide, known with masses of sea whips as Waubs Gulch. For your safety please do not swim, The Castle – two massive granite boulders, sandwiched snorkel or dive in Waubs Gulch. It is subject to frequent together, with a swim-through lined with sea whips and boating traffic and strong currents and swells. The marine yellow zoanthids, and packed with schools of bullseyes, cardinalfish, banded morwong and rock lobster reserve is best accessed via commercial operators or LEGEND Golden Bommies – two 10m high pinnacles glowing with private boat. -

A Short History of the Highlands Hill and Monykebbock Tramway

A Short History of the Highlands Hill and Monykebbock Tramway By A. White-Settler Introduction to the Second Edition On hearing ‘Highlands’ in connection with Scotland, images of the hills and mountains towards the middle and the west of the country usually come to mind. In this case however, ‘Highlands’ is the local name given to a small area of rolling countryside to the north of Dyce in Aberdeenshire, close to the village of Newmachar. The Highlands Hill and Monykebbock Tramway (to give it its full name) was a short narrow gauge line originally built to serve a pair of crofts in that area by taking feed out to the fields, quarrying stone for boundary walls and collecting ‘Swailend Earth’, used as fertile topsoil for local growers. In later years, it was used by a local college to provide courses for light railway operations, and to support forestry courses, and became home for the Garioch Industrial Narrow Gauge Railway Society (G.I.N.G.R.S.). In conversation (and often in writing), most people would call it “The Highlands Tramway” or simply “The Tramway”. What follows is a very short history of an obscure line, built up from snippets of conversation in various pubs and small businesses around the area. It is thought that the line fell out of use in the late 1960s; an increasingly small number of people have distant memories of the tramway, and I have been unable to find any reference to it in any library or local newspaper archives. Although the local farmer kindly granted me access to his land, it would appear that all but a few traces of the tramway have been obliterated, and so whilst I have made my best efforts to make this history as comprehensive as possible, unfortunately the accuracy of any information that follows cannot always be assured. -

Ideas to Inspire

2016 - Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design Speyside Whisky Festival Dunrobin Castle Dunvegan Castle interior Harris Tweed Bag Ideas to inspire Aberdeenshire, Moray, Speyside, the Highlands and the Outer Hebrides In 2016 Scotland will celebrate and showcase its historic and contemporary contributions to Innovation, Architecture and Events: Design. We’ll be celebrating the beauty and importance of our Spirit of Speyside Whisky Festival - Early May – Speyside whiskies are built heritage, modern landmarks and innovative design, as well famous throughout the world. Historic malt whisky distilleries are found all as the people behind some of Scotland’s greatest creations. along the length of the River Spey using the clear water to produce some of our best loved malts. Uncover the development of whisky making over the Aberdeenshire is a place on contrasts. In the city of Aberdeen, years in this stunning setting. www.spiritofspeyside.com ancient fishing traditions and more recent links with the North Festival of Architecture - throughout the year – Since 2016 is our Year of Sea oil and gas industries means that it has always been at the Innovation, Architecture and Design, we’ll celebrate our rich architectural past and present with a Festival of Architecture taking place across the vanguard of developments in both industries. Aberdeenshire, nation. Morayshire and Strathspey and where you can also find the Doors Open Days - September – Every weekend throughout September, greatest density of castles in Scotland. buildings not normally open to the public throw open their doors to allow visitors and exclusive peak behind the scenes at museums, offices, factories, The rugged and unspoiled landscapes of the Highlands of and many more surprising places, all free of charge. -

THE PINNING STONES Culture and Community in Aberdeenshire

THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire When traditional rubble stone masonry walls were originally constructed it was common practice to use a variety of small stones, called pinnings, to make the larger stones secure in the wall. This gave rubble walls distinctively varied appearances across the country depend- ing upon what local practices and materials were used. Historic Scotland, Repointing Rubble First published in 2014 by Aberdeenshire Council Woodhill House, Westburn Road, Aberdeen AB16 5GB Text ©2014 François Matarasso Images ©2014 Anne Murray and Ray Smith The moral rights of the creators have been asserted. ISBN 978-0-9929334-0-1 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 UK: England & Wales. You are free to copy, distribute, or display the digital version on condition that: you attribute the work to the author; the work is not used for commercial purposes; and you do not alter, transform, or add to it. Designed by Niamh Mooney, Aberdeenshire Council Printed by McKenzie Print THE PINNING STONES Culture and community in Aberdeenshire An essay by François Matarasso With additional research by Fiona Jack woodblock prints by Anne Murray and photographs by Ray Smith Commissioned by Aberdeenshire Council With support from Creative Scotland 2014 Foreword 10 PART ONE 1 Hidden in plain view 15 2 Place and People 25 3 A cultural mosaic 49 A physical heritage 52 A living heritage 62 A renewed culture 72 A distinctive voice in contemporary culture 89 4 Culture and -

The Cairngorm Club Journal 013, 1899

EXCURSIONS AND NOTES. CORRYHABBIE HILL, which was selected for the Club's COBRYHABBIE spring excursion on 1st May last, is fully described HILL. elsewhere, so that the chronicler for the day is ab- solved from all necessity of entering into topographical details. Probably the fact that the hill is little visited and is not very readily accessible led to a comparatively large attendance of members of the Club and friends, the company numbering 50. Pro- ceeding to Dufftown by an early train, the party, by special per- mission of the Duke of Richmond and Gordon, drove to Glenfiddich. Lodge, noting on the way, of course, the ruins of Auchindoun Castle. From the lodge to the summit of Corryhabbie is a walk of three miles —"three good miles", as many of the pedestrians remarked as they plodded along the rough bridle-path, which at times was deep in water and at other times thickly covered with snow, and then across the long and comparatively level plateau, rather wet and spongy and coated with soft snow. The summit had hardly been gained, how- ever, when the mist descended and obscured the view; and the party may be said to have seen little except Ben Rinnes and Glenrinnes on the one side and Cook's Cairn on the other. The customary formal meeting was held at the cairn on the summit—Rev. Robert Semple, the Chairman of the Club, presiding. Mr. Copland, deprived of the opportunity of "showing" the mountains enumerated in his list, read (from Dr. Longmuir's " Speyside ") an interesting account of the battle of Glenlivet. -

Marine Mammals and Sea Turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas

Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas MEDITERRANEAN AND BLACK SEA BASINS Main seas, straits and gulfs in the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins, together with locations mentioned in the text for the distribution of marine mammals and sea turtles Ukraine Russia SEA OF AZOV Kerch Strait Crimea Romania Georgia Slovenia France Croatia BLACK SEA Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Monaco Bosphorus LIGURIAN SEA Montenegro Strait Pelagos Sanctuary Gulf of Italy Lion ADRIATIC SEA Albania Corsica Drini Bay Spain Dardanelles Strait Greece BALEARIC SEA Turkey Sardinia Algerian- TYRRHENIAN SEA AEGEAN SEA Balearic Islands Provençal IONIAN SEA Syria Basin Strait of Sicily Cyprus Strait of Sicily Gibraltar ALBORAN SEA Hellenic Trench Lebanon Tunisia Malta LEVANTINE SEA Israel Algeria West Morocco Bank Tunisian Plateau/Gulf of SirteMEDITERRANEAN SEA Gaza Strip Jordan Suez Canal Egypt Gulf of Sirte Libya RED SEA Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas Compiled by María del Mar Otero and Michela Conigliaro The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by Compiled by María del Mar Otero IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain © IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Malaga, Spain Michela Conigliaro IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Copyright © 2012 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources With the support of Catherine Numa IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, Spain Annabelle Cuttelod IUCN Species Programme, United Kingdom Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the sources are fully acknowledged. -

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC).