Measuring US Army Effectiveness and Progress in the Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

The Cambodian Civil War and the Vietnam War

THE CAMBODIAN CIVIL WAR AND THE VIETNAM WAR: A TALE OF TWO REVOLUTIONARY WARS by Boraden Nhem A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2015 €•' 2015 Boraden Nhem All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number: 3718366 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 3718366 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 THE CAMBODIAN CIVIL WAR AND THE VIETNAM WAR: A TALE OF TWO REVOLUTIONARY WARS by Boraden Nhem Approved: _________________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: _____________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: _________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Report on the Situation in Vietnam, 20 November 1967

/'/P4 C_v Q Approved for Release: 2019/03/29 C03029772‘Y Hi , T 0p.SetIfet s.5(¢ ‘Q Q,3 $1? A( '1 NTR d J‘ “rQNa0‘<T \2.12y'- ‘ ,2.‘ meg '1, 44,, Q_\(: s ki-1- Osfarcs 0F MEMORANDUM DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE The Si/zzaz/2'0/4 in Vietnam ¥ To cret s.5(¢) 1 1 9 20 November 1967 ‘ ‘ Approved for Release: 2019/03/29 C03029772 .FAppr0ved for Release: 2019/03/29 C03029772 5 {Q =‘%s1vl=|m~ni1 ‘ mmun~ <»;1.».\ii'n~1i .\'P,(‘i1I%I'V éllisumaiilm zliicwiiinll u? nmiurmi ra /i ix: ijmieai r>é;1z@:>, ~_\.1um th~ nlcarunsl oi Hm <:sp10r~.<3¢.: law» L 5 (jade Ii ~.‘ ’>i‘i;§i(.§i=h T351, 21111; T935. s.5(¢) la 1? $ H! % ft i ‘vs I <2-2 Approved for Release: 2019/03/29 C03029772 4 Approved for Release: 2019/03/29 C03029772 3 - ad; lt£§;>ELAin1 '\t 5(0) s.5(¢) Information as of 1600 20 November 1967 \ \ s.5(¢) HIGHLIGHTS Fighting has broken out again southwest of Dak To, and US forces took serious losses in one engage- ment. In the air war, intensive North Vietnamese air defense measures have resulted in the loss of 18 US aircraft in the past five days. I. The Military Situation in South Vietnam: Re- newed fighting occurred southwest of Dak To.9 South Vietnamese paratroopers have concluded a three—day sweep northeast of the US base (Paras. 1-4). The dis- position of Communist main force units in III Corps suggests further attacks (Paras. 5-8). -

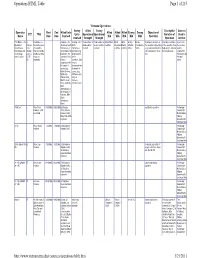

Page 1 of 215 Operations HTML Table 3/21/2011

Operations HTML Table Page 1 of 215 Vietnam Operations Enemy Allied Enemy Descriptive Sources Operation Start End Allied Units Allied Allied Allied Enemy Enemy Objective of CTZ TAO Units Operational Operational Narrative of Used in Name Date Date Involved KIA WIA MIA KIA WIA Operation Involved Strength Strength Operation Archive "The Name of the S. Description of A listing of the A listing of the Total number of Total number of Allied Killed- Allied Allied Enemy Enemy Descriptive narrative of Descriptive narrative A List of all Operation". Vietnam the tactical area American, South North allied soldiers enemy soldiers in-Action Wounded- Missing- Killed-in- Wounded-in- the operation's objectives of the operation from the sources Sometimes a Corps of operation. Vietnamese, or Vietnamese involved involved in-Action in-Action Action Action (e.g. search-and-destroy, beginning to end and used to Vietnamese and Tactical This can include other allied units and Viet Cong reconnaissance in force, its consequences. compile the an American Zone (I, provinces, cities, involved in the units involved etc.) information by name is given. II, III, towns, or operation. Each in the title and IV) landmarks. force is operation. Each author. designated with force is its branch of designated with service (e.g. its branch of USA=US Army, service (e.g. USMC=US PAVN=People's Marine Corps, Army of USAF= US Air Vietnam, Force, USN=US VC=Viet Cong) Navy, ARVN=Army of the Republic of Vietnam, VNN= South Vietnamese Navy) "Vinh Loc" I Thua Thien 9/10/1968 9/20/1968 2d -

Tet Offensive, 9Th Inf. Div, 392633

UNCLASSIFIED AD NUMBER AD392633 CLASSIFICATION CHANGES TO: unclassified FROM: confidential LIMITATION CHANGES TO: Approved for public release, distribution unlimited FROM: Controlling DoD Organization. Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development [Army], Washington, DC 20310. AUTHORITY AGO D/A ltr, 29 Apr 1980; AGO D/A ltr, 29 Apr 1980 THIS PAGE IS UNCLASSIFIED CONFIDENTIAL DEPARTMUNr OF THE ARMY 'oI N.. POPOF ADJtW ENURAL IN lUYMM TO / ALAM. p (mf) (5 Aug 68) FOR OT RD 682266 21 August 1968 ( SUBJECT: operational Report - Lessons Learned, Headquarters, 9th Infantry Division, Period Ending 30 April 1968 (U) Sj9I DISTRIBUTION Ct 1. Subject report is forwarded for review and evaluation in accordance with paragraph 5b, AR 525-15. Evaluations and corrective actions should be reported to ACSFOR OT RD, Operational Reports Branch, within 90 days 41 of receipt of covering letter. 2. Information contained in this report is provided to insure that the I Army realizes current benefits from lessons learned during recent opera- (.., tione, 3. To insure that the information provided through the Lessons Learned L-t Program is readily available on a continuous basis, a cumulative Lessons --- Learned Index containing alphabetical listings of itemo appearing in the & reports is compiled and distributed periodically, Recipients of the 4 . attached report are encourAged to recoinnd items from it for inclusion " ' 'Ein the Index by completing and returning the self-addressed form provided. qt at the and of this report. .,4 !1 1 0 r.,, BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF THE ARHY: Las -G. +IC. $ KEN 1. j , : asMajor General# USA -- "+4 , DISTf,,UOI r - .- ... -

The Development of Combat Effective Divisions in the United States Army

THE DEVELOPMENT OF COMBAT EFFECTIVE DIVISIONS IN THE UNITED STATES ARMY DURING WORLD WAR II A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Peter R. Mansoor, B.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 1992 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Allan R. Millett Williamson Murray ~~~ Allan R. Millett Warren R. Van Tine Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I express sincere appreciation to Dr. Allan R. Millett for his guidance in the preparation of this thesis. I also would like to thank Dr. Williamson Murray and Dr. John F. Guilmartin for their support and encouragement during my research. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Richard Sommers and Dr. David Keough at the United States Army Military History Institute in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, and Dr. Timothy Nenninger and Dr. Richard Boylan at the Modern Military Records Branch of the National Archives in Suitland, Maryland. Without their professional assistance, I would not have been able to complete the research for this thesis. As always, my wife Jana and daughter Kyle proved to be towers of support, even when daddy "played on the computer" for hours on end. ii VITA February 28, 1960 . Born - New Ulm, Minnesota 1982 . B.S., United States Military Academy, West Point, New York 1982-Present ......... Officer, United States Army PUBLICATIONS "The Defense of the Vienna Bridgehead," Armor 95, no. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1986): 26-32. "The Second Battle of Sedan, May 1940," Military Review 68, no. 6 (June 1988): 64-75. "The Ten Lean Years, 1930-1940," editor, Armor 96, no. -

Item D Number °3138 D Not Scanned

item D Number °3138 D Not Scanned Author Tolson, John J. Corporate Author Report/Article Tills JOUrnal/BOOk Title Airmobility 1961 -1971 Year 1973 Month/Day Color D Number of Images 26 Documents were filed together by Alvin Young under the label, "Review of Vietnam Program". U.S. GPO Stock Number 0820-00479. Selected pages mainly including figures. Friday, November 16, 2001 Page 3138 of 3140 VIETNAM STUDIES AIRMOBILITY 1961-1971 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY VIETNAM STUDIES AIRMOBILITY 1961-1971 by Lieutenant General John J. Tolson 304- DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY WASHINGTON, D.C., 1973 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 72-600371 First Printing For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.80 Stock Number 0820-00479 CHART 1—IST CAVALRY DIVISION (AIRMOBILE) ORGANIZATION 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) 1 11 X II X II III III s O CxO Support X m / \ Air Cavalry Division Artillery I Signal Battalion XI 1 Engineer Division Support Squadron 3 Brigade Battalion Aviatioi Group Command Headquarters ,a II II 1 II II ^-i 0 ceo CCO Maneuver 00 oo Battalions £ II 1 1 Aerial Artillery i Aviation Battery 1 Medium \ 2 Light Helicopter 3 105 Howitzer Battalion Helicopter i Battalions Battalions i Battalion 15,787 Officers and Men 5 Infantry 1Aviation C eneral 434 Aircraft Battalions CxO Support 1,600 Vehicles -j_ 3 Airborne C ompany ilions will have an a, One Brigade Headquartt•rs and 3 Infantry Batti -_ Infantry Airborne Capability Battalions b Maneuver Battallions wiII be assigned to 13ri«i Jes as Required ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS SOUTH VIETNAM Do Lai AUTONOMOUS MUNICIPALITY o is I CORPS II CORPS C4PITAU SPECIAL ZONE IV CORPS MAP 1 76 AIRMOBILITY MAP 2 X-RAY (Map 2) out of the possible landing zones as the best potential position for the initial air assault. -

Twin Threats: Main Forces and Guerrillas in Vietnam, the U.S

Dale Andrade and Lieutenant Colonel James H. Willbanks, U.S. Army, Retired, Ph.D. S THE UNITED STATES ends its third year forces were organized into regiments and divisions, Aof war in Iraq, the military continues to search and between 1965 and 1968 the enemy emphasized for ways to deal with an insurgency that shows no main-force war rather than insurgency.1 During the sign of waning. The specter of Vietnam looms large, war the Communists launched three conventional and the media has been filled with comparisons offensives: the 1968 Tet Offensive, the 1972 Easter between the current situation and the “quagmire” of Offensive, and the final offensive in 1975. All were the Vietnam War. The differences between the two major campaigns by any standard. Clearly, the insur- conflicts are legion, but observers can learn lessons gency and the enemy main forces had to be dealt from the Vietnam experience—if they are judicious with simultaneously. in their search. When faced with this sort of dual threat, what For better or worse, Vietnam is the most prominent is the correct response? Should military planners historical example of American counterinsurgency gear up for a counterinsurgency, or should they (COIN)—and the longest—so it would be a mistake fight a war aimed at destroying the enemy main to reject it because of its admittedly complex and forces? General William C. Westmoreland, the controversial nature. An examination of the paci- overall commander of U.S. troops under the Military fication effort in Vietnam and the evolution of the Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), faced just Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development such a question. -

The War in South Vietnam the Years of the Offensive 1965-1968

THE UNITED STATES AIR FORCE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA The War in South Vietnam The Years of the Offensive 1965-1968 John Schlight Al R FORCE Histbru and 9 Museums PROGRAM 1999 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Schlight, John The war in South Vietnam: the years of the offensive, 1965-1968 (The United States Air Force in Southeast Asia) Bibliography: p. 385 Includes Index 1. Vietnamese conflict, 1961-1975-Aerial operations, American. 2. United States. Air Force-History-Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975. I. Title. 11. Series. DS558.8.S34 1988 959.704'348"~ 19 88-14030 ISBN 0-912799-51-X ii Foreword This volume, the latest published by the Office of Air Force History in the United States Air Force in Southeast Asia series, looks at the Air Force’s support of the ground war in South Vietnam between 1965 and early 1968. The book covers the period from the time when the United States began moving from an advisory role into one of active involvement to just before the time when the United States gradually began disengaging from the war. The final scene is the successful air campaign conducted during the Communists’ siege of the Marine camp at Khe Sanh. While the actual siege lasted from late January to the middle of March 1968, enemy preparations for the encirclement-greatly increased truck traffic and enemy troop move- ments-were seen as early as October 1967. A subsequent volume in the Southeast Asia series will take up the story with the Communists’ concurrent Tet offensive during January and February 1968. -

Vietnam War: Cedar Falls - Junction City: a Turning Point

Vietnam War: Cedar Falls - Junction City: A Turning Point This monograph, written in 1974, contains specific details on the Operations Cedar Falls and Junction City which took place during the first five months of 1967 and were the first multidivisional operations in Vietnam to be conducted according to a preconceived plan. BACM RESEARCH WWW.PAPERLESSARCHIVES.COM Vietnam War: Cedar Falls - Junction City: A Turning Point This monograph, written in 1974, contains specific details on the Operations Cedar Falls and Junction City which took place during the first five months of 1967 and were the first multidivisional operations in Vietnam to be conducted according to a preconceived plan. Part of the Department of Defense Vietnam Studies Series. Topics covered include: Operation Cedar Falls; Operation Junction City; Military planning; Military operations; South Vietnam; 25th Infantry Division; 1st Infantry Division About BACM Research – PaperlessArchives.com BACM Research/PaperlessArchives.com publishes documentary historical research collections. Materials cover Presidencies, Historical Figures, Historical Events, Celebrities, Organized Crime, Politics, Military Operations, Famous Crimes, Intelligence Gathering, Espionage, Civil Rights, World War I, World War II, Korean War, Vietnam War, and more. Source material from Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), National Security Agency (NSA), Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), Secret Service, National Security Council, Department of Defense, Joint Chiefs of Staff, -

Lessons Learned, Headquarters, 25Th Infantry Division, Period Ending 31 October 1969 (U)

UNCLASSIFIED AD NUMBER AD508335 CLASSIFICATION CHANGES TO: unclassified FROM: confidential LIMITATION CHANGES TO: Approved for public release, distribution unlimited FROM: Distribution authorized to U.S. Gov't. agencies and their contractors; Administrative/Operational Use; 01 NOV 1969. Other requests shall be referred to Office of the Adjutant General, Washington, DC 20310. AUTHORITY 30 Nov 1981, DoDD 5200.10; AGO D/A ltr, 29 Apr 1982 THIS PAGE IS UNCLASSIFIED SECURITY MARKING The classified or limited status of this report applies to each page, unless otherwise marked. Separate page printouts MUST be marked accordingly. THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS INFORMATION AFFECTING THE NATIONAL DEFENSE OF THE UNITED STATES WITHIN THE MEANING OF THE ESPIONAGE LAWS, TITLE 18, U.S.C., SECTIONS 793 AND 794. THE TRANSMISSION OR THE REVELATION OF ITS CONTENTS IN ANY MANNER TO AN UNAUTHORIZED PERSON IS PROHIBITED BY LAW. NOTICE: When government or other drawings, specifications or other data are used for any purpose other than in connection with a defi- nitely related government procurement operation, the U.S. Government thereby incurs no responsibility, nor any obligation whatsoever; and the fact that the Government may have formulated, furnished, or in any way supplied the said drawings, specifications, or other data is not to be regarded by implication or otherwise as in any manner licensing the holder or any other person or corporation, or conveying any rights or permission to manufacture, use or sell any patented invention that may in any way be related thereto. 14 "4 :CONFIDENTIAL DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY OFFICE OF THE ADJUTANT GENERAL WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Dispatches Vol

Dagwood Dispatches Vol. 26-No. 4 October 2016 Issue No. 89 NEWSLETTER OF THE 16th INFANTRY REGIMENT ASSOCIATION Mission: To provide a venue for past and present members of the 16th Infantry Regiment to share in the history and well-earned camaraderie of the US Army’s greatest regiment. News from the Front The 16th Infantry Regiment Association is a Commemorative Partner with the United States World War I Commemorative Commission and with the Department of Defense Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Vietnam War Iron Rangers at the National Training Center Preparatory to their deployment to South Korea in late September, the Soldiers of the1st Battalion, 16th Infantry conducted a successful rotation to the National Training Center at Fort Irwin,. CA. By all accounts, the Iron Rangers performed in a superb manner and were declared ready for operations in the Land of the Morning Calm. The battalion began its deployment in late September and will be in Korea for nine months working for the 2nd Infantry Division. All Association members should stand by for Operation YULETIDE RANGER in December. No Mission Too Difficult No Sacrifice Too Great Duty First! Governing Board Other Board Officers Association Staff President Board Emeritii Chaplain Steven E. Clay LTG (R) Ronald L. Watts Bill Rodefer 307 North Broadway Robert B. Humphries (941) 423-0463 Leavenworth, KS 66048 Woody Goldberg [email protected] (913) 651-6857 Emeritus & Founding Member [email protected] Veterans Assistance Officer COL (R) Gerald K. Griffin Scott Rutter First Vice President Honorary Colonel of the Regiment (845) 709-4104 Bob Hahn Ralph L.