City of Oxford Architectural Survey Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C 6 Representation Act Ontario

Ontario: Revised Statutes 1937 c 6 Representation Act Ontario © Queen's Printer for Ontario, 1937 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso Bibliographic Citation Representation Act , RSO 1937, c 6 Repository Citation Ontario (1937) "c 6 Representation Act," Ontario: Revised Statutes: Vol. 1937: Iss. 1, Article 10. Available at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso/vol1937/iss1/10 This Statutes is brought to you for free and open access by the Statutes at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ontario: Revised Statutes by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. 74 Chap. 6. REPR£SEXTATIO:-:. Sec. 1. SECTION III. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY AND ELECTIONS. CHAPTER 6. The Representation Act. Boundaries to be th088 1. Notwithstanding anything in any general or special Act e:detlnS" "t puslng of the oounuariL'S of any county, terriwrial district, city, town, Act. village or township shall for the purposes of this Act be deemed to be the boundaries of such county, territorial district, city, lawn, village or township as defined by statute, by-law, proclamation or other lawful authority at the time of the passing of this Act. 1933, c. 56, s. 2. :-lumber or representa. 2. The Legislative Assembly of Ontario shall consist of tlves. ninety members. 1933, c. 56, s. 3. Dlvlelon of PrO\'lnce 3. The Province of Ontario shall for the purpose of repre Into electoral sentation in the Assembly be divided into electoral districts districts. as enumerated and defined in schedule A to this Act and for each of such electoral districts one member shall be returned to tile Assembly. -

00MC Norfolk Agricultural Census 1844, 1848, 1850 Microfilm

22/07/2020 ShelfNumber Title 00MC Norfolk Agricultural Census 1844, 1848, 1850 Microfilm 00MC 1851 Oxford County C975 Microfilm 00MC 1851 East Zorra, West Zorra, County of Oxford C973 Microfilm 00MC 1851 Oxford County C974 Microfilm 00MC 1851 Brant County C11714 Microfilm 00MC 1851 Brant County C11713 Microfilm 00MC 1851 Yarmouth Township C11719 Microfilm 00MC 1851 West Oxford, Dereham, Norwich, Blenheim C11745 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Oxford Agricultural Census C1062 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Blenheim, Dereham, Embro, Ingersoll, East Nissouri, North Norwich, South Norwich 00MC 1861 Ontario County. Oxford County: Blandford, Blenheim C1059 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Brant County: Brantford, Brantford Township C1008 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Brant County: Burford, Dumfries, Oakland, Brantford C1009 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Brant County: Brantford C1010 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Norwich South, Oxford North, East, West, Woodstock, Zorra East, West C1061 Microfilm 00MC 1861 Yarmouth Township C1019 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Brant County C9914 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Brant County C9914 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Brant County C9915 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Brant County C9916 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Oxford County C610 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Oxford County C9910 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Oxford County and Brant County C9912 - 5 Microfilm 00MC 1871 Oxford County C9913 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Oxford County C13267 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Tillsonburg C13263 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Blandford, Blenheim C13268 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Dereham, Tillsonburg C13266 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Brant C13264 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Brant C13263 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Elgin C13265 Microfilm 00MC 1881 Elgin C13266 Microfilm 00MC 1891 Elgin (T?) Microfilm 00MC 1891 Brant T6325 Microfilm 00MC 1891 Brant T6326 Microfilm 00MC 1891 Brant (T?) Microfilm 22/07/2020 ShelfNumber Title 00MC 1891 Nippising and Norfolk T6355 Microfilm 00MC 1891 Oxford T6360 Microfilm 00MC 1891 Oxford T6361 Microfilm 00MC 1910 Washington: Walla Walla T621-1673 Microfilm 00MC 1901 Nippising, Norfolk T06484 Microfilm 00MC Collector's Rolls 855009 M141 Microfilm 00MC Wesleyan Methodist Baptismal Registers Vol. -

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. ' VOLUME 87. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1920. NUMBER 37. * ΡΔ**· fjKR&lCK Rot Following Potato Blight. Oxford Baptist Association. FEDERAL AID FOR ROADS THE FAMEES. of the Oxfori Attorneys at Law. AMONG When late or "mat" occur· on NORWAY. The annual meeting blight will be bel< NEW ENGLAND NEWS more or United Baptist Association ; bithkl. maiub. potato field· leu rot, particu- New England will receive 13,108,· in Canton on and Sep Herrleà. «ltaqr C.Pufc. larly od soil·, la anre to follow. Tbnredaj Friday, 406.98 for federal aid road bail ijneoo i heavy tember 28 and 24. ding The Maine Experiment Sta- IlUa Grace who baa been ι of '•SPUD THB PLOW." Agricultural Welch, of association are: IN TABLOID FORM under the final apportionment d. park. aaked whether it la a ο The officers tbis T^BIBT SHOES— tion is frequently her home In Romford for ooople the available funds made public by 1 beet to the at onoe, where tbe baa returned to tbls Moderator—Bey. H. M. Purrfngton, Méchut Auctioneer, dig orop week·, Tillage. of Maksa- Licensed la or to delay Mr·. Marshall Pitta of Harrison ha Vails. department agriculture. foliage blighting badly, Treasurer—Rev. Clarence Emery PARIS. » MAINS, after the Clerk and c h mette obtained the largest al- SOCTU harvesting till some time tope been apeodlog several days with be Mexico. Judging: Milk Cows. are Thla has P. Mexico. Items of Merest From AT lotment, with a total of t re» Mcxler»le· for all occasions and for entirely dead. -

Family and Autism Support Centers of Massachusetts

FAMILY SUPPORT CENTERS CENTRAL/ WEST REGION North Quabbin Family Support Center- GAAAFSN Address: 361 Main Street, Athol, MA 01331 BERKSHIRE AREA Phone: (978) 249-4052 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unitedarc.org Berkshire County Arc Berkshire County Arc Central & Southern Berkshire County Family Support Center HOLYOKE/CHICOPEE AREA Address: 395 South Street, Pittsfield, MA 01201 133 Quarry Hill Road, Lee, MA 01238 Multicultural Community Services Phone: (413) 499-4241 MCS Family Support Center Email: [email protected] Address: 260 Westfield Road, Holyoke, MA Website: www.bcarc.org 01040 Phone: (413) 534-3299 United Cerebral Palsy (2 sites) Email: [email protected] UCP Central and Northern Berkshire Family Website: www.mcsnet.org Support Center Address: 535 Curran Highway, North Adams, NORTH CENTRAL AREA MA 01247 Phone: (413) 664-9345 Email: [email protected] Seven Hills Family Services Website: www.ucpwma.org Family Support Center of North Central Address: 1460 John Fitch Highway, Fitchburg, UCP Central and Northern Berkshire Family MA 01402 Support Center Phone: (978) 632-4322 Address: 208 West Street, Pittsfield, MA 01201 Website: www.sevenhills.org Phone: (413) 442-1562 Email: [email protected] Centro Las Americas Cultural/Linguistic- Website: www.ucpwma.org Specific Family Support Center Multicultural Family Development Center Address: 437 Main Street, Fitchburg, MA 01420 FRANKLIN/HAMPSHIRE AREA Phone: (978) 343-5836 Email: [email protected] The Association for Community Living Website: www.centroinc.org Family Empowerment Specific -

C 5 Representation Act Ontario

Ontario: Revised Statutes 1914 c 5 Representation Act Ontario © Queen's Printer for Ontario, 1914 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso Bibliographic Citation Representation Act , RSO 1914, c 5 Repository Citation Ontario (1914) "c 5 Representation Act," Ontario: Revised Statutes: Vol. 1914: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/rso/vol1914/iss1/8 This Statutes is brought to you for free and open access by the Statutes at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ontario: Revised Statutes by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. :)4 Chap. 5. IlEPIIESE:\'T.\TIQX. Sec. 1. SECTION III. LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY AND ELECTIONS. CHAPTER ". All Act r~spcctillg Hcprescntalioll of the People 10 the Legislative Assembly. IS .:\JAJ-ESTY, b)' and with the 3dviee and consent of th(l Legislative Assembly of the Province of Ontario, Henacts as follows:- 1. This Act may be cited as The Representation Act. S Ed\\'. VII. c. 2, s. 1. lIllUp,...,lllli..". :.!. fll tliTs Ad, ~:I~"'I<',.,,1 <1I~lrlc'l (a) "Rleetoral district" shall mean a place entitled to <lcrlne<l, return a member or members to the Assembly; COIl"lle~. Territorl.. l (b) Wher(l counties and territorial districts are referred <l1"lrl,'I,. to they shnll, unless it is otherwise expressly provided, be deemed to be such counties and territorial districts respec lI.oY. SIal. r. 3. tively as constituted or defined by The Territorial Division Act, and the cities, towns and "mages herein referred to are those mentioned in the statutes, by-laws or proclamations, describin~ or dcfillin~ sneh cities, lowns or villages for mnnicipal purposes. -

Belleville Subdivision

BELLEVILLE SUBDIVISION COUNTIES: LANARK, FRONTENAC,LENNOX& ADDINGTON, HASTINGS, NORTHUMBERLAND, DURHAM AND METRO CP MILEAGE COUNTY MUNICIPALITY FROM TO Lanark Smiths Falls Town 0.00 0.60 Lanark Montague Twp 0.60 1.44 Lanark Drummond/North Elmsley Twp (North Elmsley Twp) 1.44 10.20 Lanark Drummond/North Elmsley Twp (Drummond Twp) 10.20 11.20 Lanark Perth Town 11.20 12.91 Lanark Bathrust Burgess Sherbrooke Twp (Bathurst Twp) 12.91 23.08 Lanark Bathrust Burgess Sherbrooke Twp (South Sherbrooke T 23.08 31.00 Frontenac Central Frontenac Twp 31.00 36.58 Frontenac South Frontenac Twp 36.58 40.19 Frontenac Central Frontenac Twp 40.19 53.97 Lennox & Addington Stone Mills Twp 53.97 54.73 Lennox & Addington Stone Mills Twp 54.73 67.97 Lennox & Addington Greater Napanee Town 67.97 74.01 (Richmond Twp) Hastings Tyendinaga Twp 74.01 85.46 Hastings Belleville City 85.46 94.27 Hastings Quinte West City 94.27 108.84 Northumberland Brighton Mun. 108.84 114.85 Northumberland Cramahe Twp 114.85 121.34 Northumberland Alnwick/Haldimand Twp 121.34 130.5 Northumberland Hamilton Twp 130.5 134.04 Northumberland Cobourg Town 134.04 136.18 Northumberland Hamilton Twp 136.18 140 Northumberland Port Hope & Hope Town 140.00 149.81 Durham Clarington Mun. 149.81 170.71 Durham Oshawa City 170.71 175.87 Durham Whitby Town 175.87 181.47 Durham Ajax Town 181.47 185.97 Durham Pickering Town 185.97 191.97 Metro Toronto City (Scarborough City) 191.97 202.35 Metro Toronto City (North York City) 202.35 205.21 Metro Toronto City (East York Borough) 205.21 207.89 Metro Toronto -

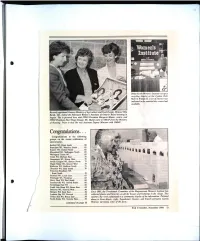

Congratulations

Brant North Women's Institute set up a recycling display at the Lynden Park Mall in Brantford. A lot of interest was indicated in the material the women had available. Recently appointed Ontario Ministry of Agriculture and Food Deputy Minister Rita Burak, left, visited the Federated Women's Institutes of Ontario Board meeting in August. She is pictured here with FWIO President Margaret Munro, centre, and FWIO President Elect Peggy Knapp. Ms. Burak came to OMAF finm the Ministry of Housing. Prior to that she was Assistant Deputy Minister with OMAF. Congratulations . Congratulations to the following groups on the recent celebration of anniversaries . Burford WI, Brant South . 90 Branchton WI, Waterloo South . 85 Kintore WI, Oxford North . .85 Moorefield WI, Wellington North . .85 Wellington Centre WI . 85 Cavan WI, Durham East . .75 Dungannon WI, Huron West . 75 Jarratt-Cre igton WI, Simcoe North . .75 Maple Valley WI, Simcoe West . .75 Rushview WI, Dufferin North . .75 Gleneden WI, Grey South . 70 Princeton-Woodbury WI , Brant South . .70 Fairfield WI, Leeds East . 65 Pittsburgh WI, Fro ntenac . .. 65 Derry West WI, Peel South . 60 Summerville WI, Oxford South . .60 Tyendinaga East WI . 60 South Line Brant WI, Bruce East . .55 Bolsover WI, Victoria West . 40 Palmyra WI, Kent East . 40 Since 1985, the Tweedsmuir Committee of the Magnetawan Women's Institute has Lookout Bay WI, Prescott . .35 collected photos and histories on all the houses and buildings in the village. This Gillies Hill WI, Bruce East . .30 summer, the work culminated in a community display of the information . Pictured North Emily WI, Victo ria West . -

Canada 1852 Sub-District Table

Estimated population by sub-district, Canada 1852 UPPER CANADA Sub-district names Estimated pop 1 Addington District 1 Amherst Island 1287 2 Camden 6975 3 Earnestown 5111 4 Sheffield 1792 Total of Addington 15165 2 Brant District 5 Brantford 6410 6 Brantford Town 3877 7 Burford 4433 8 Dumfries South 4297 9 Oakland 840 10 Onondaga 1858 11 Paris Village 1890 12 Tuscarora 1821 Total of Brant 25426 3 Bruce District 13 Arran 149 14 Brant 621 15 Bruce 100 16 Carrick 17 Culross not yet settled 18 Elderslie 14 19 Greenock 244 20 Huron 236 21 Kincardine 1149 22 Kinloss 47 23 Saugeen 277 Total of Bruce 2837 4 Carleton District 24 Fitzroy 2807 25 Gloucester 3005 26 Goulbourne 2525 27 Gower, North 1777 28 Huntley 2519 29 March 1125 30 Marlborough 2053 31 Nepean 3800 32 Osgood 3050 33 Richmond Village 434 34 Torbolton 542 Total of Carleton 23637 5 Dundas District 35 Matilda 4198 36 Mountain 2764 37 Williamsburg 4284 38 Winchester 2565 Total of Dundas 13811 6 Durham District 39 Cartwright 1756 40 Cavan 4438 41 Clarke 6190 42 Darlington 8005 43 Hope 5299 44 Manvers 2568 45 Port Hope, (Town) 2476 Total of Durham 30732 7 Elgin District 46 Aldborough 1226 47 Bayham 5092 48 Dunwich 1948 49 Dorchester 1477 50 Malahide 4050 51 Southwold 5063 52 Yarmouth 5288 53 St. Thomas, Village 1274 Total of Elgin 25418 8 Essex District 54 Anderdon 1199 55 Colchester 1870 56 Gosfield 1802 57 Maidstone 1167 58 Malden 1315 59 Mersea 1193 60 Rochester 788 61 Sandwich 4928 62 Amherstburg, Town 1880 63 Tilbury West 675 Total of Essex 16817 9 Frontenac District 64 Clarendon 65 -

Ontario Local History ( Additions Are Regularly Made to Last Pages)

1 Ontario Local History ( additions are regularly made to last pages) Title Author Topic Yr Condition Format Price The Early Days of Innerkip District (Updated) Zella Hotson Detailed story of families 84 fine p/b $6 & buildings in the area The Danube Swabians: A People with Portable Katherine Stenger Frey Life & immigration of 82 fine h/b w $15 Roots Danube Germans to Can d/w Rural Ontario: Photographs of 19 th Century Ontario Verschoyle Blake & Stunning photos of bldgs 69 Very h/b w $10 Ralph Greenhill & landscape from 1800s good d/w Remembrance of Things Past: 1905-1977 Kathleen Morris Rivers A long life lived in Owen 77 good p/b $5 Sound area coil Towers of Time: Photo History of Ontario’s Clock Marc Boileau (signed) Federal architects & their 06 new p/b $23 Tower Post Offices, 1871-1936 Ontario post offices Kingsville 1790-2000: A Stroll Through Time Kingsfield-Gosfield Wide range of historical 03 fine p/b $7 Volume 1 Heritage Society essays on Kingsville area Kingsville 1790-2000: A Stroll Through Time Kingsfield-Gosfield Wide range of historical 03 fine p/b $7 Volume 2 (both for $12) Heritage Society essays on Kingsville area Hamilton: Story of a City Lois C Evans Quick & easy history of good p/b $3 Steeltown Magnetic Muskoka: Yesterday, Today and Muriel Grigg Traces her family history 71 good h/b w $5 Tomorrow with the area’s growth d/w A Guide to Historic Haileybury Peter Fancy and Tem / 40 pp street-by-street tour 93 Fine p/b $4 Abitibi Heritage Ass’n of the 1889 village twice destroyed by fire. -

Directory of Ontario Jurisdictions Cross-Referenced by Health Unit

Directory of Ontario Jurisdictions Cross- referenced by Health Unit © Produced and compiled by the Association of Local Public Health Agencies, 2008 Public Health Unit Names Updated 2020 City Health Unit Region ABBEY SUDBURY NORTH EAST ABBOTSFORD PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ABBOTT TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERARDER LAMBTON SOUTH WEST ABERDEEN TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERDEEN GREY-BRUCE SOUTH WEST ABERDEEN ADDITIONAL ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABERFELDY LAMBTON SOUTH WEST ABERFOYLE WELLINGTON-DUFFERIN CENTRAL WEST ABIGO TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABINGDON NIAGARA CENTRAL WEST ABINGER KINGSTON EASTERN ABITIBI CANYON PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ABIWIN NORTHWESTERN NORTH WEST ABNEY TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ABOTOSSAWAY TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABRAHAM TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ABREY TP THUNDER BAY NORTH WEST ACADIA TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ACANTHUS NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACHESON TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ACHIGAN ALGOMA NORTH EAST ACHILL SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ACHRAY NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACOUCHICHING NORTH BAY NORTH EAST ACRES TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ACTINOLITE HASTINGS EASTERN ACTON TP ALGOMA NORTH EAST ACTON HALTON CENTRAL WEST ACTON CORNERS LEEDS EASTERN ADAIR TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADAMS PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADAMSON TP THUNDER BAY NORTH WEST AMSVILLE GREY-BRUCE SOUTH WEST ADANAC TP PORCUPINE NORTH EAST ADDINGTON HIGHLANDS TP KINGSTON EASTERN ADDISON TP SUDBURY NORTH EAST ADDISON LEEDS EASTERN ADELAIDE MIDDLESEX SOUTH WEST ADELAIDE METCALFE TP MIDDLESEX SOUTH WEST ADELARD RENFREW EASTERN ADIK ALGOMA NORTH EAST ADJALA SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ADJALA-TOSORONTIO TP SIMCOE CENTRAL EAST ADMASTON RENFREW EASTERN -

Final Recommendations on the Future Electoral Arrangements for Oxfordshire County Council

Final recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Oxfordshire County Council Report to The Electoral Commission July 2004 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version please contact The Boundary Committee for England: Tel: 020 7271 0500 Email: [email protected] The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD 03114G. This report is printed on recycled paper. Report no: 373 2 Contents Page What is The Boundary Committee for England? 5 Summary 7 1 Introduction 21 2 Current electoral arrangements 25 3 Draft recommendations 33 4 Responses to consultation 35 5 Analysis and final recommendations 41 6 What happens next? 75 Appendix A Final recommendations for Oxfordshire: detailed mapping 77 3 4 What is The Boundary Committee for England? The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of The Electoral Commission, an independent body set up by Parliament under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. The functions of the Local Government Commission for England were transferred to The Electoral Commission and its Boundary Committee on 1 April 2002 by the Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (SI No. 3962). The Order also transferred to The Electoral Commission the functions of the Secretary of State in relation to taking decisions on recommendations for changes to local authority electoral arrangements and implementing them. -

A. Norman Sands Local History Collection ONTARIO (PROVINCE)

A. Norman Sands Local History Collection ONTARIO (PROVINCE): Ontario - General Ontario - Churches Chruches Ontario - Conservation of Natural Resources Ontario - Economic Development Ontario - History Ontario - Tourism Brant (County) Brant (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Burford Twp. Farringdon Oakland Twp. Paris Salt Springs Scotland Village South Dumfries Twp. Brant (County) - Brantford Bruce (County) Bruce (County) - Towns & Townships A-R Amabel Twp. Arran Twp. Carluke Chepstow Colpoy's Bay Glamis Lion's Head Paisley Port Elgin Ripley Riversdale Bruce (County) - Towns & Townships S-Z South Kinloss Tara Teeswater Tiverton Walkerton Wiarton Bruce (County) - Chesley Bruce (County) - Kincardine Bruce (County) - Southampton Carleton (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Fitzroy Harbour Huntley Twp. Kenmore March Twp. Osgoode Twp. Richmond Stittsville Torbolton Twp. Carleton (County) - Ottawa Carleton (County) - Ottawa - Churches A-K Carleton (County) - Ottawa - Churches L-Z Dufferin (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Grand Valley Horning's Mills Mulmur Twp. Orangeville Elgin (County) Elgin (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Aldborough Twp. Aylmer Bayham Twp. Dutton Sparta Springfield Union Vienna Yarmouth Twp. Elgin (County - Port Stanley Elgin (County) - St. Thomas Essex (County) Essex (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Belle River Colchester Harrow Kingsville Leamington Maidstone Twp. Sandwich Tecumseh Twp. Walkerville Essex (County) - Amherstburgh Essex (County) - Windsor Frontenac (County) Frontenac (County) - Towns & Townships A-Z Abbey Dawn Barriefield