Pelicanology with Juita Martinez Ologies Podcast June 3, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Civil Society Support a Good Practice Guide for Birdlife Partners

Building Civil Society support A Good Practice Guide for BirdLife Partners © RS PB BirdLife International and Vogelbescherming Nederland endeavour to Suggested citation: BirdLife International provide accurate and up-to-date information; however, no representations (2021) Building Civil Society Support: or warranties of any kind, express or implied, are made about the A Good Practice Guide for BirdLife Partners. completeness, accuracy, reliability or suitability of the information contained Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International. in this document or any other information given in connection with this Report written and compiled by Sue Stolton, document. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly Hannah Timmins and Nigel Dudley, at your own risk. BirdLife International and Vogelbescherming Nederland Equilibrium Research. shall have no liability arising from the use by any party of the information contained in this document or given by BirdLife International and Design: Miller Design Vogelbescherming Nederland in connection with this document and, to the Illustrations: dogeatcog extent permitted by law, excludes all liability howsoever caused, including A PDF copy of this publication is available but not limited to any direct, indirect or consequential loss, loss of profit, loss on the BirdLife International Partnership of chance, negligence, costs (including reasonable legal costs) or any other Extranet partnership.birdlife.org/login.action liability in tort, contract or breach of statutory duty. Building Civil Society support A Good Practice Guide for BirdLife Partners This is the third in the series of action, as well as developing a civil ‘Good Practice Guides’ produced society constituency, governance, by the Capacity Development management, communications and Programme of BirdLife International. -

Owlspade 2020 Web 3.Pdf

Owl & Spade Magazine est. 1924 MAGAZINE STAFF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 COLLEGE LEADERSHIP EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lachicotte Zemp PRESIDENT Zanne Garland Chair Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. MANAGING EDITOR Jean Veilleux CABINET Vice Chair Erika Orman Callahan Belinda Burke William A. Laramee LEAD Editors Vice President for Administration Secretary & Chief Financial Officer Mary Bates Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Michael Condrey Treasurer Zanne Garland EDITORS Vice President for Advancement Amy Ager ’00 Philip Bassani H. Ross Arnold, III Cathy Kramer Morgan Davis ’02 Carmen Castaldi ’80 Vice President for Applied Learning Mary Hay William Christy ’79 Rowena Pomeroy Jessica Culpepper ’04 Brian Liechti ’15 Heather Wingert Nate Gazaway ’00 Interim Vice President for Creative Director Steven Gigliotti Enrollment & Marketing, Carla Greenfield Mary Ellen Davis Director of Sustainability David Greenfield Photographers Suellen Hudson Paul C. Perrine Raphaela Aleman Stephen Keener, M.D. Vice President for Student Life Iman Amini ’23 Tonya Keener Jay Roberts, Ph.D. Mary Bates Anne Graham Masters, M.D. ’73 Elsa Cline ’20 Debbie Reamer Vice President for Academic Affairs Melissa Ray Davis ’02 Anthony S. Rust Morgan Davis ’02 George A. Scott, Ed.D. ’75 ALUMNI BOARD 2019-2020 Sean Dunn David Shi, Ph.D. Pete Erb Erica Rawls ’03 Ex-Officio FJ Gaylor President Sarah Murray Joel B. Adams, Jr. Lara Nguyen Alice Buhl Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Chris Polydoroff Howell L. Ferguson Vice President Jayden Roberts ’23 Rev. Kevin Frederick Reggie Tidwell Ronald Hunt Elizabeth Koenig ’08 Angela Wilhelm Lynn M. Morton, Ph.D. Secretary Bridget Palmer ’21 Cover Art Adam “Pinky” Stegall ’07 Dennis Thompson ’77 Lara Nguyen A. -

The Chat May 2021

Number 469 The Chat May 2021 A voice for education and conservation in the natural world Rogue Valley Audubon Society www.roguevalleyaudubon.org Deadline for the June issue is May 20 Virtual MAY Program Tuesday, May 25 at 7:00 pm “The Woodpecker’s Tongue and Other Avian Adaptations” Presented by DAN GLEASON Editor's note: We don't usually have a May chapter meeting. This bonus event takes the place of our annual May picnic which was canceled. Awakened by a woodpecker drumming on your gutters at 5 a.m.? Or was one tapping on a nearby street sign? No, they aren’t trying to dig out your gutters, nor have their brains been addled! Banging your head against a tree all day may not seem like a productive way to spend your life, but woodpeckers are adapted to do just that, and they do so very successfully. There are a number of fascinating adaptations found in woodpeckers that facilitate this mode of living, along with many other adaptations that occur throughout the bird world. Dan will discuss some of the most unusual and generally little-known special- ized bird adaptations. Topics he’ll cover in this program go beyond woodpeck- ers and include other fascinating adaptations that help birds. Many of these ad- aptations are not found in field guides, so many people are not aware of them. Indeed, they make birds among the most fascinating of creatures to study and learn about. Join us for a fascinating look at Avian Adaptations! About Dan An Oregon native, Dan Gleason was on the faculty of the University of Oregon Biol- ogy Department for 30 years, and taught Ornithology for senior graduate-level biol- ogy majors for 35 years. -

City of Girls Elizabeth Gilbert

AUSTRALIA JUNE 2019 City of Girls Elizabeth Gilbert The blazingly brilliant new novel from Elizabeth Gilbert, author of the international bestseller Eat Pray Love: a glittering coming-of-age epic stitched across the fabric of a lost New York Description It is the summer of 1940. Nineteen-year-old Vivian Morris arrives in New York with her suitcase and sewing machine, exiled by her despairing parents. Although her quicksilver talents with a needle and commitment to mastering the perfect hair roll have been deemed insufficient for her to pass into her sophomore year of Vassar, she soon finds gainful employment as the self-appointed seamstress at the Lily Playhouse, her unconventional Aunt Peg's charmingly disreputable Manhattan revue theatre. There, Vivian quickly becomes the toast of the showgirls, transforming the trash and tinsel only fit for the cheap seats into creations for goddesses. Exile in New York is no exile at all: here in this strange wartime city of girls, Vivian and her girlfriends mean to drink the heady highball of life itself to the last drop. And when the legendary English actress Edna Watson comes to the Lily to star in the company's most ambitious show ever, Vivian is entranced by the magic that follows in her wake. But there are hard lessons to be learned, and bitterly regrettable mistakes to be made. Vivian learns that to live the life she wants, she must live many lives, ceaselessly and ingeniously making them new. 'At some point in a woman's life, she just gets tired of being ashamed all the time. -

Western Field Ornithologists September 2020 Newsletter

Western Field Ornithologists September 2020 Newsletter Black Skimmers, Marbled Godwits, and Forster’s Terns. Imperial Beach, San Diego County. 3 September 2009. Photo by Thomas A. Blackman. Christopher Swarth, Newsletter Editor http://westernfieldornithologists.org/ What’s Inside…. Farewell from President Kurt Leuschner Welcome to New Board Members Alan Craig Remembers the Early Days of WFO Jon and Kimball on Bird Taxonomy and the NACC Western Regional Bird Highlights by Paul Lehman Steve Howell: A Big Year by Foot in Town Over-eager Nuthatches and Willing Sapsuckers Meet the WFO Board Members Awards and new WFO Leadership Kimball’s Life and Covid-time in a New Home Book reviews Student Research Field Notes and Art Announcements and News Kurt Leuschner’s President’s Farewell These past two years have been an interesting time to be the President of Western Field Ornithologists. We had one of our most successful conferences in Albuquerque, and just before the lockdown we completed a very memorable WFO field trip to Tasmania. We accomplished a lot together, and I look forward to assisting with future planning when the world opens up again – and it will! While we may not know exactly what lies ahead, we certainly won’t take anything for granted. We’re in the midst of a worldwide discourse about the serious impacts of social injustice. How the ornithological community can help improve the experiences of minorities in field ornithology continues to be on our minds as we move forward into 2021. Our new WFO Diversity and Inclusivity subcommittee has met two times already, and we will continue to discover and to implement ways to bring more under- represented groups into the world of birds. -

Racial Equity & Social Justice Resources for the Sustainability In

Racial Equity & Social Justice Resources for the Sustainability in Higher Education Community This collection of racial equity and social justice resources was initiated by the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee of the AASHE Advisory Council to highlight the vital work of the many incredible people and organizations who have been doing powerful work to bring attention to issues of racial and social justice. The resources are in no particular order and include links to programs and resources related to solidarity and messaging, understanding racial/social/environmental justice, race and sustainability, anti-racism, prominent influencers, podcasts, videos and articles. We encourage everyone to add to and revisit this open-source document to continue learning about racial equity and social justice issues. Solidarity Resources/Messaging ● Solidarity Messaging ● Showing Up for Racial Justice ● Medium ● University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment ● A Guide to Culturally Conscious Identifiers and Emojis Toolkits ● The Campus Divestment From Police College and University Toolkit ● American University’s Environmental Justice Toolkit Racial/Social/Environmental Justice-Understanding the Issues ● Movement for Black Lives ● Showing up for Racial Justice ● Black Lives Matter ● NAACP Environmental Justice ● Indigenous Environmental Network ● https://www.mpd150.com/ ● Campaign Zero ● Color of Change ● Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law ● Diverse: Issues in Higher Education ● Reform Alliance ● Human Rights Watch ● The Climate -

The Echo Makers

cover To find the soul it is necessary to lose it. —A. R. Luria Contents Part One: I Am No One Part Two: But Tonight on North Line Road Part Three: God Led Me To You Part Four: So You Might Live Part Five: And Bring Back Someone Else Part One I Am No One We are all potential fossils still carrying within our bodies the crudities of former existences, the marks of a world in which living creatures flow with little more consistency than clouds from age to age. —Loren Eiseley, The Immense Journey, “The Slit” Cranes keep landing as night falls. Ribbons of them roll down, slack against the sky. They float in from all compass points, in kettles of a dozen, dropping with the dusk. Scores of Grus canadensis settle on the thawing river. They gather on the island flats, grazing, beating their wings, trumpeting: the advance wave of a mass evacuation. More birds land by the minute, the air red with calls. A neck stretches long; legs drape behind. Wings curl forward, the length of a man. Spread like fingers, primaries tip the bird into the wind’s plane. The blood-red head bows and the wings sweep together, a cloaked priest giving benediction. Tail cups and belly buckles, surprised by the upsurge of ground. Legs kick out, their backward knees flapping like broken landing gear. Another bird plummets and stumbles forward, fighting for a spot in the packed staging ground along those few miles of water still clear and wide enough to pass as safe. -

Fall 2020 Wisconsin Natural Resources

All in toboost Alarming drop in populations spurs actions around the state LISA GAUMNITZ birds Lynn Christiansen of Saukville It’s exactly what conservationists say “No matter where you live and no must happen if we are to save the birds matter how much land you influence, traded the perennials in her that delight our eyes and ears, serve as you can have a positive impact for birds flower beds for native species pollinators, seed dispersers, pest control and the insect species that many of and added dogwood trees, native and food for other wildlife, and anchor them depend on for food,” he says. a birdwatching industry that generated grasses, shrubs and a bur oak. $107 billion nationally in economic NUMBERS CONFIRM WORST FEARS When she moves to a 3-acre site impact, 666,000 jobs and $13 billion in Hard numbers now confirm what near Grafton this year, she plans tax revenue in 2011. many bird lovers have noticed for years National studies are revealing a steep at their feeders, along roadsides and in to double down on native land- loss of birdlife in North America since fields and woods: Birds and birdsong scaping for birds. 1970 as science hammers home the con- are disappearing from our lives. North cept that conserving birds means protect- America has 2.9 billion fewer breeding Cattle producer Jerry Marr uses rota- ing them throughout their life cycle. birds than there were in 1970, repre- tional grazing, enrolls some of his family’s “Before the early 2000s, the focus of senting a net loss of nearly 30%. -

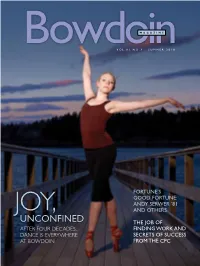

Unconfined the Job of After Four Decades, Finding Work and Dance Is Everywhere Secrets of Success at BOWDOIN from the CPC SUMMER 2010 CONTENTS Bowdoinm a G a Z I N E

M a g a z i n e BowdoinV o l . 8 1 N o . 3 S u m m e r 2 0 1 0 ForTuNe’S GoodForTuNe: ANdySerwer’81 Joy, ANdoTherS uNcoNFiNed TheJoBoF After four decAdes, FiNding Work and dAnce is everywhere SecreTSoFSucceSS At BOWDOIN From thecPc suMMer 2010 contents BowdoinM a g a z i n e 16 LetJoybe Unconfined PhotogrAPhs By BoB hAndelMAn In honor of four decades of dance at Bowdoin, and in recognition of the ways in which the dance program is inclusive and expansive, we decided to take the dancers out of their typical performance spaces and photograph them appearing in campus spots both familiar and unexpected. 30 Fortune’sGoodFortune By doug Boxer-cook • PhotogrAPhs By kArsten MorAn Director of News and Media Relations Doug Boxer-Cook visits with Fortune Magazine editor Andy Serwer ’81. In addition to Serwer, the global business publication has the good fortune to have other Bowdoin graduates writing and working there. 42 TheJobofFinding Work By iAn Aldrich • PhotogrAPhs By deAn ABrAMson Bowdoin students have graduated into a tough economy for the last couple of years. Thankfully, director Tim Diehl and others at Bowdoin’s Career Planning Center, with valued assistance from “the Bowdoin network,” are ready to help. dePArTmeNTS Mailbox 2 Bookshelf 6 Bowdoinsider 8 Alumnotes 52 class news 53 weddings 79 obituaries 86 | l e t t e r | Bowdoin From theediTor MAgAZine volume 81, number 3 the gifts of summer summer, 2010 aine summers are full of messages to us. -

The State of Inclusive Science Communication: a Landscape Study

The State of Inclusive Science Communication: A Landscape Study Katherine Canfield and Sunshine Menezes Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island Graphics by Christine Liu This report was developed for the University of Rhode Island’s Metcalf Institute with generous support from The Kavli Foundation and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Cite as: Canfield, K. & Menezes, S. 2020. The State of Inclusive Science Communication: A Landscape Study. Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island. Kingston, RI. 77 pp. Executive Summary Inclusive science communication (ISC) is a new and broad term that encompasses all efforts to engage specific audiences in conversations or activities about science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) topics, including, but not limited to, public engagement, informal science learning, journalism, and formal science education. Unlike other approaches toward science communication, however, ISC research and practice is grounded in inclusion, equity, and intersectionality, making these concerns central to the goals, design, implementation, evaluation, and refinement of science communication efforts. Together, the diverse suite of insights and practices that inform ISC comprise an emerging movement. While there is a growing recognition of the value and urgency of inclusive approaches, there is little documented knowledge about the potential catalysts and barriers for this work. Without documentation, synthesis, and critical reflection, the movement cannot proceed as quickly as is warranted. The University of Rhode Island’s Metcalf Institute conducted a landscape study to address this gap and clarify the state of ISC with support from The Kavli Foundation. This document summarizes the findings from interviews of thirty ISC leaders whose work spans career stages, disciplines, sectors, and modes. -

'I Am Here Fighting for My Life and Future Children'

Demonstrators for Black lives Militarized police ‘I am here Birders against racism fighting for my life Vol. 52 / July 2020 No. 7 • hcn.org and future children’ –SKYE, LOS ANGELES EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR/PUBLISHER Greg Hanscom EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brian Calvert ART DIRECTOR Cindy Wehling DIGITAL EDITOR Gretchen King ASSOCIATE EDITORS Emily Benson, Paige Blankenbuehler, Graham Lee Brewer, Maya L. Kapoor PHOTO EDITOR Roberto (Bear) Guerra ASSOCIATE PHOTO EDITOR Luna Anna Archey ASSISTANT EDITORS Jessica Kutz, Carl Segerstrom, Anna V. Smith EDITOR AT LARGE Betsy Marston COPY EDITOR Diane Sylvain CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Elena Saavedra Buckley, Ruxandra Guidi, Michelle Nijhuis, McKenna Stayner, Jonathan Thompson CORRESPONDENTS Leah Sottile, Sarah Tory EDITORIAL FELLOWS Nick Bowlin, Kalen Goodluck, Helen Santoro Anagi Crew hunts a 30-foot male bowhead whale on the Bering Sea in an umiaq, a small sealskin boat that is prized for its light weight, stealthy movement and respect for tradition. Yves Brower DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR Laurie Milford SENIOR DEVELOPMENT OFFICER Paul Larmer MAJOR GIFT ADVISER Alyssa Pinkerton DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATES Hannah Stevens, Carol Newman SENIOR MARKETER JoAnn Kalenak EVENTS & BUSINESS PARTNER COORDINATOR Laura Dixon IT MANAGER Alan Wells DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS Erica Howard ACCOUNTS ASSISTANT Mary Zachman CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER Kathy Martinez CUSTOMER SERVICE Karen Howe, Mark Nydell, Tammy York Know GRANT WRITER Janet Reasoner FOUNDER Tom Bell the BOARD OF DIRECTORS Brian Beitner (Colo.), John Belkin (Colo.), Seth Cothrun (Calif.), Jay Dean (Calif.), Bob Fulkerson (Nev.), Wayne Hare (Colo.), West. Laura Helmuth (Md.), Samaria Jaffe (Calif.), Nicole Lampe (Ore.), Marla Painter (N.M.), High Country News is an independent, reader-supported nonprofit 501(c)(3) independent media organization that covers Bryan Pollard (Ark.), Raynelle Rino (Calif.), the important issues and stories that define the Western U.S. -

Blackafinstem with Various Ologists Ologies Podcast June 10, 2020

Very Special Episode: BlackAFinSTEM with various Ologists Ologies Podcast June 10, 2020 Oh Heeey, it's that coconut cream pie with the pastry crust that’s pretty good but would've been better with a graham cracker crust, buy anyway, Alie Ward, back with the MOST special episode of Ologies, maybe ever. Literally, maybe my favorite ever. So let's get to it, ASAP. First off, thank you to everyone who has been rating, and subscribing, and who leaves reviews. You know I read them all, and I pick out a fresh one. Thank you ‘Lwhgnjshshuu’. I promise you that I'm going to get more sleep - next week. Okay, if you listened to last week’s episode, Pelicanology with Juita Martinez, you likely have pelicans on the brain, saggy sacks and all, and hopefully you celebrated last week’s Black Birders Week, the inaugural one. It ran from May 31st through June 5th, and it was launched a reaction to some recent, really distressing events. And zoologist and wildlife enthusiast Corina Newsome is one of the cofounders of Black Birders Week, and she announced it to her ever-growing Twitter audience of over 60,000 people last week. [clip of Corina Newsome speaking:] For far too long, Black people in the United States have been shown that outdoor exploration activities such as birding are not for us - whether it be because of the way the media chooses to present who is the outdoorsy type, or the racism experienced by Black people when we do explore the outdoors, as we saw recently in Central Park.