Genre in Janáček's Operas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janáček, Religion and Belief

MUSICOLOGICA BRUNENSIA 44, 2009, 1–2 JOHN TYRRELL (CARDIFF) Janáček, religion and belief Famously in his final year, Janáček repudiated his pupil Ludvík Kundera’s con- tention that the ‘old man’ had at last made his peace with God and become again a believer. ‘Not an old man, not a believer! Young man!’ he wrote indignantly to him.1 Leoš Janáček was baptized into the Catholic Church2 and given Christian names (Leo Eugen) that celebrated papal and saintly associations rather than fam- ily ones.3 Church-going was a part of his young family life, as vividly described in his famous feuilleton Without Drums JW XV/199, and it became even more so when at the age of eleven he was enrolled as a resident chorister at the Au- gustinian Monastery in Staré Brno. The adults who surrounded him there were mostly monks, including his music teacher Pavel Křížkovský; on the few occa- sions he managed to get away it was to stay with his priest-uncle Jan Janáček, who took over responsibility for him after the death of his father in 1866. It was at the Augustinian Monastery, presumably, that he was confirmed into the Catholic Church. If there is doubt about this it is only because of the lack of documen- tation.4 Janáček was due to be confirmed on the eve of his thirteenth birthday in June 1867, but in a letter to Jan Janáček he announced that he should have ‘gone for holy confirmation’, but ‘since I had no clothes, again I couldn’t go.’5 1 LJ to Ludvík Kundera (Prague, 8 February 1928; reproduced in Bohumír Štědroň: Leoš Janá- ček v obrazech [Leoš Janáček in pictures] (Státní pedagogické nakladatelství, Prague, 1982), 43. -

Chamber Music by Bernard Hoffer

ChamberA Celebration Music Acknowledgments by A Celebration & Concerto di Camera V recorded Jan. 13, 2020; Concerto di Camera IV recorded Bernard Hoffer Sept. 28, 2017; Lear in the Wildeness recorded Jan. 10, 2018; Musica Sacra recorded Jan. 12, 2018; Musica Profana recorded Jan. 11, 2018; Paul Revere’s Ride recorded Jan. 12, 2018. All works recorded at Fraser Performance Studio, WGBH Educational Foundation, Boston Sound Engineer: Antonio Oliart Edited, Mixed, and Mastered by Tom Hamilton at the Pickle Factory, New York City WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM BOSTON MUSICA VIVA TROY1820-21 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 RICHARD PITTMAN, CONDUCTOR TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2020 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. Hoffer_1820-21_book.indd 1-2 4/9/20 4:47 PM The Composer The Music Bernard Hoffer was born October 14, 1934 in Zurich, A Celebration Switzerland. He came to the United States in 1941 and received A Celebration is a three minute Bagatelle, written Feb. 2019 to celebrate 50 years early musical training at the Dalcroze School in New York of Boston Musica Viva. studying composition with Max Wald (a student of d’Indy) and counterpoint with Kurt Stone. Hoffer attended the Eastman Concerto di Camera V School of Music, where he received a B.M. and an M.M., study- Written between 2017-19, this is the last of my Concerto di Camera series. The ing composition with Bernard Rogers and Wayne Barlow and previous ones featured the piano, cello, clarinets, and violin in my Capriccio conducting with Paul White and Herman Genhart. -

RNCM OPERA the CUNNING LITTLE VIXEN LEOŠ JANÁČEK WED 02, FRI 04, MON 07 DEC | 7.30PM SUN 06 DEC | 3PM RNCM THEATRE

WED 02 - MON 07 DEC RNCM OPERA The CUNNING LITTLE VIXEN LEOŠ JANÁČEK WED 02, FRI 04, MON 07 DEC | 7.30PM SUN 06 DEC | 3PM RNCM THEATRE LEOŠ JANÁČEK The CUNNING LITTLE VIXEN The Cunning Little Vixen Music by Leoš Janáček Libretto by Leoš Janáček based on the novella by Rudolf Těsnohlídek, translated by David Pountney Translation © David Pountney Used with permission of David Pountney. All Rights Reserved. 3 SYNOPSIS CAST THE ADVENTURES OF THE VIXEN BYSTROUŠKA Emyr Jones*, Ross Cumming** Forester Act I Pasquale Orchard*, Alicia Cadwgan** Vixen Sharp-Ears How they caught Bystrouška Georgia Mae Ellis*, Melissa Gregory** Fox Goldenmane Bystrouška in the courtyard of Lake Lodge Philip O’Connor*, Gabriel Seawright** Schoolmaster/Mosquito Bystrouška in politics Liam Karai*, George Butler** Priest/Badger Bystrouška gets the hell out Ema Rose Gosnell*, Lila Chrisp** Forester’s Wife/Owl Ranald McCusker*, Samuel Knock** Rooster/Mr Pásek Act II Sarah Prestwidge*, Zoë Vallée** Chocholka/Mrs Pásek Bystrouška dispossesses William Kyle*, Thomas Ashdown** Harašta Bystrouška's love affairs Rebecca Anderson Lapák Bystrouška's courtship and love Lorna Day Woodpecker Katy Allan Vixen as a Cub Interval Georgia Curwen Frantík/Cricket Emily Varney Pepík/Frog Act III Anastasia Bevan Grasshopper/Jay Bystrouška outran Harašta from Líšeň How the Vixen Bystrouška died RNCM OPERA CHORUS DANCER FOX CUBS The baby Bystrouška - the spitting image of her mother Lleucu Brookes Jade Carty Lleucu Brookes Jade Carty Jade Carty Dominic Carver HENS Abigail Jenkins James Connolly -

Janáček (1854–1928) the Cunning Little Vixen (Příhody Lišky Bystroušky), JW I/9 (1923) Opera in Three Acts, Libretto by Leoš Janáček on a Text by Rudolf Těsnohlídek

The Cunning Little Vixen Sinfonietta Sir Simon Rattle Lucy Crowe Gerald Finley Sophia Burgos Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) The Cunning Little Vixen (Příhody lišky Bystroušky), JW I/9 (1923) Opera in three acts, libretto by Leoš Janáček on a text by Rudolf Těsnohlídek. Opéra en trois actes, livret de Leoš Janáček, à partir d’un texte de Rudolf Těsnohlídek. Oper in drei Akten, Libretto von Leoš Janáček beruhend auf einem Text von Rudolf Těsnohlídek. Sinfonietta, Op. 60, JW VI/18, “Sokol Festival” (1926) Sinfonietta recorded live in DSD 256fs on 18–19 September 2018, and The Cunning Little Vixen recorded live in DSD 128fs during semi-staged performances (directed by Peter Sellars) on 27 & 29 June 2019, at the Barbican, London. Concerts produced by LSO and the Barbican. The Cunning Little Vixen and Sinfonietta published by Universal Edition A.G., Wien Andrew Cornall producer Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes and Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd engineering, editing and mixing Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd mastering engineer © 2020 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK P 2020 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK 2 The Cunning Little Vixen – Cast Revírník / Forester / Der Förster / Le Garde forestier (ou Garde-chasse) Gerald Finley bass-baritone Paní revírníková / Forester’s Wife / Die Försterin / La femme du Garde forestier Paulina Malefane soprano Rechtor / Schoolmaster / Der Schulmeister / Le Maître d’école Peter Hoare tenor Farář / Parson / Der Pfarrer / Le curé Jan Martiník bass -

UNLV Symphonic Winds, UNLV Flute Ensemble, and Sin City Winds

Wind Ensemble Ensembles 4-17-2014 UNLV Symphonic Winds, UNLV Flute Ensemble, and Sin City Winds Anthony LaBounty University of Nevada, Las Vegas Adam Hille University of Nevada, Las Vegas Keith Larsen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Adam Steff University of Nevada, Las Vegas Jennifer Grim University of Nevada, Las Vegas SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_wind_ensemble Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation LaBounty, A., Hille, A., Larsen, K., Steff, A., Grim, J., Cao, C., UNLV Graduate Sextet (2014). UNLV Symphonic Winds, UNLV Flute Ensemble, and Sin City Winds. 1-6. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_wind_ensemble/40 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Wind Ensemble by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Anthony LaBounty, Adam Hille, Keith Larsen, Adam Steff, Jennifer Grim, Carmella Cao, and UNLV Graduate Sextet This -

Leoše Janáčka Leoš Janáček

Hudební fakulta Janáčkovy akademie múzických umění, Brno Nadace Leoše Janáčka, Brno Soutěž se uskutečňuje The competition will take place Faculty of Music of the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing za finanční podpory: thanks to financial support from: Arts in Brno in partnership with Leoš Janáček Foundation Statutárního města Brna Statutory City of Brno Jihomoravského kraje Region of South Moravia Ministerstva kultury ČR Ministry of Culture CZ vypisuje 16. ročník Leoše Mezinárodní soutěže Janáčka announces Leoš 16th Janáček International Competition v oboru/in fi eld Prezident soutěže/President of the Competition: zpěv Prof. Ing. MgA. Ivo Medek, Ph.D. Děkan HF JAMU/Dean of Faculty of Music, JAMU Předseda poroty/Chairman of the Jury: voice doc. Magdaléna Hajóssyová Ve čtyřletých cyklech soutěže se pravidelně střídají obory: 7. – 12. září 2009 smyčcové kvarteto (2010); housle (2011); klavír (2012); zpěv (2013) 7 – 12 September 2009 In four-year cycles the following disciplines regularly take turns: String Quartet (2010); Violin (2011); Piano (2012); Voice (2013) Kontakt/Contact: HF JAMU – SLJ MgA. Kateřina Polášková CZ – 662 15 Brno Komenského nám. 6 tel./phone: +420 542 591 606 fax: +420 542 591 633 e-mail: [email protected] Více informací na/For more information: http://hf.jamu.cz jamu_brozura2009.indd 1-4 29.8.2008 11:36:18 jamu_brozura2009.indd 5-8 29.8.2008 11:36:42 Faculty of Music of the Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Brno soprano A. Dvořák “Saint Ludmila“ - aria of Ludmila No. 14 „O dovol, o dovol…“ in partnership with Leoš Janáček Foundation A. Dvořák “Bridal Shirt“ - aria of Bride „Žel bohu, žel, kde můj tatíček…“ under the patronage of Governor of the Region of South Moravia and Mayor of the Statutory City of Brno mezzo/alto A. -

HARMONIA Leoš Janáček: Life, Work, and Contribution

HARMONIA Leoš Janáček: Life, Work, and Contribution Special Issue ▪ May 2013 The Journal of the Graduate Association of Musicologists und Theorists at the University of North Texas Editor Clare Carrasco Associate Editors Abigail Chaplin J. Cole Ritchie Benjamin Dobbs Jessica Stearns Andrea Recek Joseph Turner Typesetters Clare Carrasco Emily Hagen Abigail Chaplin J. Cole Ritchie Benjamin Dobbs Jessica Stearns Jeffrey Ensign Joseph Turner Faculty Advisor for Special Issue Dr. Thomas Sovík GAMuT Executive Committee Andrea Recek, President Benjamin Graf, Vice President Emily Hagen, Secretary Jeffrey Ensign, Treasurer GAMuT Faculty Advisor Dr. Hendrik Schulze http://music.unt.edu/mhte/harmonia HARMONIA Leoš Janáček: Life, Work, and Contribution Special Issue ▪ May 2013 CONTENTS From the Editor 1 Leoš Janáček: Biography 3 JENNIFER L. WEAVER Reconsidering the Importance of Brno's Cultural Milieu for the 8 Emergence of Janáček's Mature Compositional Style ANDREW BURGARD The Originality of Janáček's Instrumentation 22 MILOŠ ORSON ŠTĚDROŇ The Search for Truth: Speech Melody in the Emergence of 36 Janáček's Mature Style JUDITH FIEHLER Does Music Have a Subject, and If So, Where is it? Reflections on 51 Janáček's Second String Quartet MICHAEL BECKERMAN, Keynote Speaker Untangling Spletna: The Interaction of Janáček's Theories and the 65 Transformational Structure of On an Overgrown Path ALEXANDER MORGAN Offstage and Backstage: Janáček's Re-Voicing of Kamila Stösslová 79 ALYSSE G. PADILLA Connecting Janáček to the Past: Extending a Tradition of 89 Acoustics and Psychology DEVIN ILER Childhood Complexity and Adult Simplicity in Janáček’s 96 Sinfonietta JOHN K. NOVAK Leoš Janáček: “The Eternally Young Old Man of Brno” 112 CLARE CARRASCO The Czech Baroque: Neither Flesh nor Fish nor Good Red Herring 121 THOMAS SOVÍK About the Contributors 133 From the Editor: It is my pleasure to introduce this special issue of Harmonia, the in- house journal of the Graduate Association of Musicologists und Theorists (GAMuT) at the University of North Texas. -

Kata-Kabanova-Tisk-1416384334.Pdf

KATA_KABANOVA_SKLADACKA.QXD:Sestava 1 11/19/14 8:15 AM Stránka 1 NATIONAL MORAVIAN-SILESIAN THEATRE OPERA Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) KÁŤA KABANOVÁ / Katya Kabanova So much love within me but so little for me… Wioletta Chodowicz (Káťa) and Jana Sýkorová (Varvara) © Martin Popelář Antonín Dvořák Theatre © Martin Popelář Roman Sadnik (Tichon) and Wioletta Chodowicz (Káťa) © Martin Popelář Jiří Myron Theatre © Martin Popelář THE NATIONAL MORAVIAN-SILESIAN THEATRE The National Moravian-Silesian Theatre (based in 1919) is the biggest and oldest professional theatre in Ostrava and the Moravian-Silesian region. The theatre has four artistic companies – opera, drama, ballet and operetta/musical, which regularly perform on two theatre scenes – the Antonín Dvořák Theatre (seating capacity of 517) and the Jiří Myron Theatre (seating capacity of 623). The theatre presents 16-19 premieres per year and plays almost 500 performances. The National Moravian-Silesian Theatre organises the festival of drama theatres OST-RA-VAR and also the event European Opera Days in Ostrava. The theatre also participates in NODO/New Opera Days Ostrava (biennial). Eva Urbanová (Kabanicha) © Martin Popelář Intendant: Jiří Nekvasil Music director of Opera: Robert Jindra November 23, 2014 The City of Ostrava as the founder of the National Moravian-Silesian Theatre operates as its most significant donor. In addition, the Moravian-Silesian Region and the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic are two other significant donors of the theatre. YEAR OF CZECH MUSIC www.ndm.cz – Brno and Ostrava Autumn Conference www.opera-europa.org Arnold Bezuyen (Boris) © Martin Popelář KATA_KABANOVA_SKLADACKA.QXD:Sestava 1 11/19/14 8:15 AM Stránka 2 Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) Leoš Janáček (1854–1928) was a Czech composer, musi- SYNOPSIS cal theorist, folklorist, publicist and teacher. -

Cunning Littlevixen

LEOŠ The JANÁČEK Cunning LittleVixen Roman Trekel Paolo Rumetz Chen Reiss Hyuna Ko Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper Conducted by Tomáš Netopil Staged by Otto Schenk LEOŠ The JANÁČEK Cunning LittleVixen Conductor Tomáš Netopil After quarter of a century, legendary director Otto Schenk returns to the Orchestra Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper Wiener Staatsoper to stage Leoš Janáček’s musical fairy tale The Cunning Little Vixen, conducted by Tomáš Netopil. Chorus Chor der Wiener Staatsoper Although the opera premiered in 1924, it took more than 90 years for Stage Director Otto Schenk The Cunning Little Vixen to enter the stage of the magnificent Wiener Staatsoper. To celebrate the fact that the work is heard at the house on Forester Roman Trekel the Ring for the very first time, none other than Austrian theatre luminary Harašta Paolo Rumetz Otto Schenk devotes himself to staging the adventures of the clever fox Little Sharp Ears Chen Reiss and accompanying wildlife. With a keen eye for detail, Schenk conjures Fox Hyuna Ko up an abundant, naturalistic forest scenery, created by set designer Amra Forester's Wife/Owl Donna Ellen Buchbinder, in which the opera’s animal and human protagonists embark Schoolmaster Joseph Dennis on their life’s journey. In this magical world, Israeli soprano Chen Reiss enchants in the title role of Little Sharp Ears, gracefully and cheekily Priest/Badger Marcus Pelz roaming the woods. Opposite her Roman Trekel performs as a very likeable Pásek Wolfram Igor Derntl forester, shining with a warm baritone, while Korean Hyuna Ko brings a Pásek's Wife Jozefina Monarcha powerful soprano to her performance as the Fox. -

Leoš Janáček Mša Glagolskaja Glagolitic Mass Taras Bulba “Rhapsody for Orchestra”

Leoš Janáček Mša Glagolskaja Glagolitic Mass Taras Bulba “Rhapsody for Orchestra” Aga Mikolaj • Iris Vermillion Stuart Neill • Arutjun Kotchinian Rundfunkchor Berlin Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin Marek Janowski Leoš Janáček (1854 – 1928) Mša Glagolskaja (Missa Solemnis) Glagolitic Mass (original version 1926-1927) 1 Intrada 1. 38 2 Úvod (Introduction) 1. 58 3 Gospodi pomiluj (Kyrie) 4. 21 4 Slava (Gloria) 6. 49 5 Vĕruju (Credo) 12. 30 6 Svet (Sanctus) 6. 29 7 Agneče Božij (Agnus Dei) 3. 40 8 Varhany sólo (Postludium) - organ solo 2. 53 This organ solo is based on the original manuscript, with corrections by the composer, thus differing slightly from the printed version. 9 Intrada da capo 1. 39 Taras Bulba (1918) Rhapsody for Orchestra 10 Smrt Andrijova (The Death of Andrei) 8. 28 11 Smrt Ostapova (The Death of Ostap) 5. 19 12 Proroctví Tarase Bulbas 8. 51 (The Prophecy and the Death of Taras Bulba) Total playing-time: 64.53 Aga Mikolaj – soprano (Glagolitic Mass) Iris Vermillion – contralto (Glagolitic Mass) Stuart Neill – tenor (Glagolitic Mass) Arutjun Kotchinian – bass (Glagolitic Mass) Iveta Apkalna – organ Rundfunkchor Berlin (Glagolitic Mass) Chorus master: Simon Halsey Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin (Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin) Leader: Rainer Wolters conducted by: Marek Janowski A co-production between Deutschlandradio Kultur/ROC GmbH and PentaTone Music Recording venue : Haus des Rundfunks, RBB, Berlin and (organ solo) at the Philharmonie Berlin (11/2010 and 4/2012) Executive producers: Stefan Lang & Job Maarse Recording producer: Job Maarse Balance engineers: Everett Porter (Glagolitc Mass), Jean-Marie Geijsen (Taras Bulba) Recording engineer: Roger de Schot Editing: Ientje Mooij / Thijs Ruiter Design: Netherlads Biographien auf Deutsch und Französischfinden Sie auf unserer Webseite. -

CHAN 3101 BOOK.Qxd 6/4/07 11:35 Am Page 2

CHAN 3101 Book Cover.qxd 6/4/07 11:15 am Page 1 JANÁCEK CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH THE CUNNING LITTLE VIXEN PETER MOORES FOUNDATION CHAN 3101(2) CHAN 3101 BOOK.qxd 6/4/07 11:35 am Page 2 Leosˇ Janácˇek (1854–1928) The Cunning Little Vixen Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht The Adventures of Fox Sharp-Ears Opera in three acts Libretto by Leosˇ Janácˇek, English translation by Yveta Synek Graff and Robert T. Jones Forester....................................................................................................................Thomas Allen Cricket..................................................................................................................Stephen Wallder Caterpillar..................................................................................................................Shelley Nash Mosquito ............................................................................................................Robert Tear Schoolmaster } Frog ........................................................................................................................Piers Lawrence Vixen Cub .......................................................................................................Rebecca Bainbridge Forester’s Wife ......................................................................................................Gillian Knight Owl } Vixen Sharp-Ears ...................................................................................................Lillian Watson Dog ...........................................................................................................................Karen -

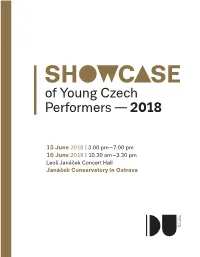

Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava SHOWCASE Is the Way How the Youngest Talented Generation of Czech Artists Performing Classical Music Has Been Introduced

15 June 2018 | 3.00 p m–7.00 pm 16 June 2018 | 10.30 a m–3.30 pm Leoš Janáček Concert Hall Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava SHOWCASE is the way how the youngest talented generation of Czech artists performing classical music has been introduced. Czech conservatories and art universities nominated young artists, out of which the jury selected 22 young interprets and singers, who present what they consider the best of their repertoire in short 15-minute performances. The showcase intended for the professionals is open to everybody interested in the way how good the emerging Czech art generation is. The Arts and Theatre Institute has organized it for the second time as an accompanying event of the Leoš Janáček International Music Festival in cooperation with the Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava. As far as the nature of the Showcase is concerned, we kindly ask you to respect the silence when you come and leave. 15 June 2018 | 3.00 p m–7.00 pm 16 June 2018 | 10.30 a m–3.30 pm Leoš Janáček Concert Hall Janáček Conservatory in Ostrava PrAguE 2018 ©2018 Arts and Theatre Institute ISBN 978-80-7008-401-4 No: IDu 734 Showcase of Young Czech Performers 2018 Prague 2018 Editor _ Lenka Dohnalová Translation _ Eliška Hulcová Graphic design _ David Cígler PRGGRLMME 15 June 2018 15:00 Opening 15:15 Kristýna Kůstková – soprano U g. rossini: The Barber of Sevilla , aria Una voce poco fa , L. Janáček: Cunning Little Vixen , aria I Stole , F. Liszt: Oh, quand je dors 15:35 Martin Strakoš – bassoon U O.