A Study of Knickpoint Formation: Geomorphic Analysis of San Simeon Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring the Effects of Knickpoint Erosion on Bridge Pier and Abutment Structural Damage Due to Scour Thanos Papanicolaou University of Iowa, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Final Reports & Technical Briefs from Mid-America Mid-America Transportation Center Transportation Center 2012 Monitoring the Effects of Knickpoint Erosion on Bridge Pier and Abutment Structural Damage Due to Scour Thanos Papanicolaou University of Iowa, [email protected] David M. Admiraal University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Christopher Wilson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Clark W. Kephart University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/matcreports Part of the Civil Engineering Commons Papanicolaou, Thanos; Admiraal, David M.; Wilson, Christopher; and Kephart, Clark W., "Monitoring the Effects of Knickpoint Erosion on Bridge Pier and Abutment Structural Damage Due to Scour" (2012). Final Reports & Technical Briefs from Mid-America Transportation Center. 3. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/matcreports/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mid-America Transportation Center at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Final Reports & Technical Briefs from Mid-America Transportation Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Report # MATC-UI-UNL: 471/424 Final Report 25-1121-0001-471, 25-1121-0001-424 Monitoring the Effects of Knickpoint Erosion ® on Bridge Pier and Abutment Structural Damage Due to Scour A.N. Thanos Papanicolaou, Ph.D. Professor Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering IIHR—Hydroscience & Engineering University of Iowa David M. Admiraal, Ph.D. Associate Professor Christopher Wilson, Ph.D. Assistant Research Scientist Clark Kephart Graduate Research Assistant 2012 A Cooperative Research Project sponsored by the U.S. -

Explain How Rivers Adjust to a Change in Base Level with Reference to Examples You Have Studied (2013 Q1C)

Isostasy | A1 Sample answer Explain how rivers adjust to a change in base level with reference to examples you have studied (2013 Q1C) Isostatic uplift is when land rises above sea level because of tectonic activity. This is usually due to a large weight being removed from the land e.g. when an ice cap melts. Eustatic changes are when the sea level drops. This is due to water being locked away somewhere e.g., in a glacier. When it melts, the sea level rises again. The River Nore in Kilkenny has experienced a change in base level. This can be seen since there are knickpoints along it, roughly 150-200m above sea level. A knickpoint can be seen when the sea level drops and a river rejuvenates because the river starts vertically eroding once more. Rejuvenation is the term used to describe a river that starts eroding like a youthful river even when it is in its old age stage. A knickpoint is a spot where the newly eroded river profile meets the old river profile. Sometimes you will find a waterfall here. River terraces are also found where rejuvenation has occurred. This is when a river forms a new floodplain that is lower down than the last. The remnants of the old floodplain are left as steps and are called terraces. If there are terraces on both sides of the river, they are called paired terraces. Terraces can be formed multiple times if the river rejuvenates more than once, appearing as a series of steps down to the river. -

Late Holocene Sea Level Rise in Southwest Florida: Implications for Estuarine Management and Coastal Evolution

LATE HOLOCENE SEA LEVEL RISE IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA: IMPLICATIONS FOR ESTUARINE MANAGEMENT AND COASTAL EVOLUTION Dana Derickson, Figure 2 FACULTY Lily Lowery, University of the South Mike Savarese, Florida Gulf Coast University Stephanie Obley, Flroida Gulf Coast University Leonre Tedesco, Indiana University and Purdue Monica Roth, SUNYOneonta University at Indianapolis Ramon Lopez, Vassar College Carol Mankiewcz, Beloit College Lora Shrake, TA, Indiana University and Purdue University at Indianapolis VISITING and PARTNER SCIENTISTS Gary Lytton, Michael Shirley, Judy Haner, STUDENTS Leslie Breland, Dave Liccardi, Chuck Margo Burton, Whitman College McKenna, Steve Theberge, Pat O’Donnell, Heather Stoffel, Melissa Hennig, and Renee Dana Derickson, Trinity University Wilson, Rookery Bay NERR Leda Jackson, Indiana University and Purdue Joe Kakareka, Aswani Volety, and Win University at Indianapolis Everham, Florida Gulf Coast University Chris Kitchen, Whitman College Beth A. Palmer, Consortium Coordinator Nicholas Levsen, Beloit College Emily Lindland, Florida Gulf Coast University LATE HOLOCENE SEA LEVEL RISE IN SOUTHWEST FLORIDA: IMPLICATIONS FOR ESTUARINE MANAGEMENT AND COASTAL EVOLUTION MICHAEL SAVARESE, Florida Gulf Coast University LENORE P. TEDESCO, Indiana/Purdue University at Indianapolis CAROL MANKIEWICZ, Beloit College LORA SHRAKE, TA, Indiana/Purdue University at Indianapolis PROJECT OVERVIEW complicating environmental management are the needs of many federally and state-listed Southwest Florida encompasses one of the endangered species, including the Florida fastest growing regions in the United States. panther and West Indian manatee. Watershed The two southwestern coastal counties, Collier management must also consider these issues and Lee Counties, commonly make it among of environmental health and conservation. the 5 fastest growing population centers on nation- and statewide censuses. -

Rivers and Base Level—Cool Stuff Earth Science Essentials by Russ Colson

Stories of Other Worlds—How to Build a Landscape Rivers and Base Level—Cool Stuff Earth Science Essentials by Russ Colson The River—The state boundary that moves. The migration of rivers has a long and complex history in human politics and war. The problem arises because rivers were commonly used to mark boundaries of adjacent political entities. When the rivers inevitably migrated, as mature streams are wont to do, disagreements arose about who owned the new land formed on the inside bend of the meanders. It seems like a simple solution would be to keep the boundaries fixed, whether the river migrates or not. That way, the land controlled by a particular political entity is not changed by the vagaries of erosion and deposition. However, suppose that the river is an important defensive barrier against attack? Clearly, in that case the border needs to be maintained along the river. Or, what if the river is important for commerce and transportation? Again, keeping the border along the river makes sense, regardless of the gain or loss of land. In his 1715 (edition) book Of the Rights of War and Peace, Hugo Grotius took the view that many rivers are defensive boundaries and ...the river, by gradually altering its course, does also alter the borders of the territory; and whatsoever the river casts up to the opposite side, shall be under his jurisdiction, to whom the augmentation is made Although geologists treat the various processes of river migration (such as erosion, deposition, meander cut offs, etc) as part of a single process, courts have often ruled that they are quite different. -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

Rapidly-Migrating and Internally-Generated Knickpoints Can Control 2 Submarine Channel Evolution 3 4 Maarten S

1 Rapidly-migrating and internally-generated knickpoints can control 2 submarine channel evolution 3 4 Maarten S. Heijnen1,2,*, Michael A. Clare1, Matthieu J.B. Cartigny3, Peter J. Talling3, Sophie 5 Hage2, D. Gwyn Lintern4, Cooper Stacey4, Daniel R. Parsons5, Stephen M. Simmons5, Ye 6 Chen5, Esther J. Sumner2, Justin K. Dix2, John E. Hughes Clarke6, 7 8 1Marine Geosciences, National Oceanography Centre, European Way, Southampton, U.K. 9 2Ocean and Earth Sciences, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, European Way, 10 Southampton, U.K. 11 3Departments of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Durham, South Rd, Durham, U. K. 12 4Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada, Box 6000, 9860 West Saanich Road, Sidney BC, 13 Canada. 14 5School of Environmental Sciences, University of Hull, U.K. 15 6Earth Sciences, Center for Coastal & Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, 24 Colovos Road, Durham, 16 U.S.A. 17 *corresponding author: [email protected] 18 19 Abstract 20 Submarine channels are the primary conduits for terrestrial sediment, organic carbon, and 21 pollutant transport to the deep sea. Submarine channels are far more difficult to monitor 22 than rivers, and thus less well understood. Here we present the longest (9 year) time-lapse 23 mapping yet for a submarine channel. Past studies suggested that gradual meander-bend 24 migration, levee-deposition, or migration of (supercritical-flow) bedforms controls the 25 evolution of submarine channels. We show for the first time how exceptionally rapid (100- 26 450 m/year) upstream migration of 5-to-30 m high knickpoints can control how submarine 27 channels evolve. -

Drainage Basin Drainage Patterns Flow

1 Distribution of Earth’s water Fig. 10.2, p. 267 2 The hydrologic cycle Processes involved in the hydrologic cycle: Fig. 10.3, p. 267 Evaporation & Transpiration Precipitation Infiltration & Runoff 3 The Hydrologic Cycle 4 Drainage basin Def.: The entire area from which a stream and its tributaries receive their water Separated from another drainage basin by a divide http://www.ndsu.nodak.edu/tricollege/watershed/image/wpe1.gif 5 Drainage Basins and Divides Def. Divide: a line that separates two drainage basins Fig. 10.30, p. 289 6 Mississippi River drainage basin Fig. 10.31, p. 290 7 Rivers of North America (lots of them flow Northward!) http://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/namerica/printpage/nanewriv.htm 8 Picture: The "Continental Divide," the line that separates the Nelson/Red River drainage basin from the Mississippi/James drainage basin is marked by a sign along I_94, midway between Valley City and Jamestown, ND. 9 Classification of Streams Drainage Patterns Flow 10 Drainage Patterns Def: Pattern of the interconnected network of streams in an area 3 common: Dendritic Radial Rectangular (Trellis) 11 Drainage Patterns Fig. 10.32, p. 291 12 Dendritic drainage pattern 13 Flow Does the stream flow on a regular basis or not? 3 types: Perennial Intermittent 1 Ephemeral 14 Stream flow Velocity Gradient Discharge 15 Velocity ft/sec or metric equivalent Fig. 10.5, p. 269 16 Gradient The slope, or vertical drop per distance ft/mile or metric equivalent Fig. 10.7, p. 271 17 Discharge Def: the volume of water moving past a given point per unit time CFS = cubic feet/second = ft3/second = channel width x channel depth x velocity Ex: 100ft (width) x 15ft (depth) x 6 ft/sec = 9000 ft3/sec 18 Laminar vs. -

Reservoir Prediction of Shallow Braided Delta Front by Comprehensive Prediction Error Filtering Analysis

E3S Web of Conferences 245, 01029 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202124501029 AEECS 2021 Reservoir prediction of shallow braided delta front by Comprehensive Prediction Error Filtering Analysis Wenjuan Li1* 1China Geological Environmental Monitoring Institute 100081 Beijing, China Abstract. For a more accurate reservoir prediction of braided delta front, the method of High Resolution Sequence Stratigraphy was adopted in Moxizhuang Oil Field with the assistance of Comprehensive Prediction Error Filter Analysis. J1s2 was divided into 2 fifth-order base-level cycles, 5 sixth-order base- level cycles, with the turnaround surfaces of base-level rise to fall, and time-equal correlation of shallow braided delta front was achieved. Through study of microfacies correlation in High Resolution Sequence Stratigraphy frame, it is apparent that base-level cycles control microfacies distribution, and furthermore reservoir distribution: reservoirs around turnaround surface of base-level falling to rising are thick and laterally connected, while reservoirs near the middle of base-level falling and base-level rising are relatively thinner and less laterally connected, and reservoirs close to the beginning of base-level falling and the end of base-level rising are undeveloped. 1 Introduction method of logging data spectrum analysis and High- Resolution Sequence Stratigraphy, which provides Moxizhuang Oilfield in the middle of Junggar Basin is theoretical guidance for the fine division, correlation and located in Gurbantunggut Desert in Mosuowan Town, prediction of reservoirs. Shihezi City, covering an area of 240Km2. Up to 2012, the proved petroleum geological reserves are 2059×104t. Moxizhuang Oilfield is structurally located at the 2 Regional geological backgrounds western tip of Mosuowan Uplift in the Central The Junggar Basin has experienced four stages: foreland Depression, a wide and gentle nose-like structure. -

A Systematic Approach and Software for the Analysis of Point Patterns On

This is a preprint. Manuscript submitted to Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 1 A systematic approach and software for 2 the analysis of point patterns on river 3 networks 4 5 Wolfgang Schwanghart1*, Christian Molkenthin2, Dirk Scherler3,4 6 7 1 Institute of Environmental Science and Geography, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, 8 Germany 9 2 Institute of Mathematics, University of Potsdam, 14476 Potsdam-Golm, Germany 10 3 German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ), Earth Surface Geochemistry, 14473 Potsdam, 11 Germany 12 4 Institute of Geological Sciences, Freie Universität Berlin, 12249 Berlin, Germany 13 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 14 15 Keywords: Point pattern analysis, point processes, fluvial geomorphology, knickpoints, beaver dams 16 17 Abstract 18 Many geomorphic phenomena such as bank failures, landslide dams, riffle-pool sequences and 19 knickpoints can be modelled as spatial point processes. However, as the locations of these phenomena 20 are constrained to lie on or alongside rivers, their analysis must account for the geometry and topology 21 of river networks. Here, we introduce a new numeric class in TopoToolbox called Point Pattern on 22 Stream networks (PPS), which supports exploratory analysis, statistical modelling, simulation and 23 visualization of point processes. We present two case studies that aim at inferring processes and 24 factors that control the spatial density of geomorphic phenomena along river networks: the analysis of 25 knickpoints in river profiles, and modelling spatial locations of beaver dams based on topographic 26 metrics. The case studies rely on exploratory analysis and statistical inference using inhomogeneous 27 Poisson point processes. -

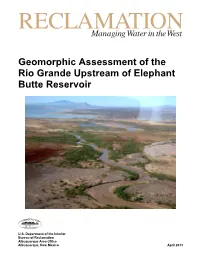

Geomorphic Assessment of the Rio Grande Upstream of Elephant Butte Reservoir

Geomorphic Assessment of the Rio Grande Upstream of Elephant Butte Reservoir U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Albuquerque Area Office Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2013 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Geomorphic Assessment of the Rio Grande Upstream of Elephant Butte Reservoir prepared by Technical Services Division River Analysis Group Nathan Holste, M.S., P.E. Hydraulic Engineer Cover Photograph: Elephant Butte Reservoir Delta, looking downstream from near RM 39 (photo taken April 23, 2013) U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Albuquerque Area Office Albuquerque, New Mexico April 2013 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary .............................................................................................. 1 Geomorphology and Channel Adjustment Concepts and Analyses................. 4 Sediment Balance.............................................................................................. 8 Drivers............................................................................................................. 10 Flow Magnitude, Frequency, and Duration ............................................. -

Modeling Delta Erosion with a Landscape Evolution Model

7HFKQLFDO5HSRUW1R65+ 0RGHOLQJ'HOWD(URVLRQZLWKD /DQGVFDSH(YROXWLRQ0RGHO 86 'HSDUWPHQW RI WKH,QWHULRU %XUHDXRI5HFOD PDWLRQ 7HFKQLFDO6HUYLFH&HQWHU 'HQYHU &RORUDGR 6HSWHPEHU 0LVVLRQ6WDWHPHQWV 7KHPLVVLRQRIWKH'HSDUWPHQWRIWKH,QWHULRULVWRSURWHFWDQG SURYLGHDFFHVVWRRXU1DWLRQ¶VQDWXUDODQGFXOWXUDOKHULWDJHDQG KRQRURXUWUXVWUHVSRQVLELOLWLHVWR,QGLDQWULEHVDQGRXU FRPPLWPHQWVWRLVODQGFRPPXQLWLHV 7KHPLVVLRQRIWKH%XUHDXRI5HFODPDWLRQLVWRPDQDJHGHYHORSDQG SURWHFWZDWHUDQG UHODWHG UHVRXUFHVLQ DQ HQYLURQPHQWDOO\DQG HFRQRPLFDOO\VRXQGPDQQHULQ WKHLQWHUHVW RIWKH$PHULFDQ SXEOLF Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 1 2.0 landscape Evolution Models 2 3.0 Discussion 3 4.0 Summary 4 5.0 References 5 1.0 Introduction The Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams were removed from the Elwha River between 2011 and 2014. The rate of removal of Glines Canyon Dam was established based on hydraulic and sediment study findings in the early 1990s. Phased notches of approximately 15 feet followed by 2 week to 2 month hold periods were planned. When dam removal was started in September 2011, field monitoring was used to track sediment erosion rates and numerical modeling was used to forecast sediment erosion rates. The integrated monitoring and modeling information was used to provide recommendations for adjusting the rate of dam removal. The rate could be increases if sed iment erosion objectives had been met for a given notch, or decreased to ensure the rate of river erosion kept pace with the rate of dam removal. Modeling was required on a quarterly basis during dam removal to inform the adaptive management program . Traditional numerical models, either 1D, 2D, or 3D were not utilized because of limitations in capturing the complexities associated with rapid and extensive vertical incision and lateral erosion of the delta during drawdowns. Another challenge was that the erosion was affected by sediment properties in the delta that varied both vertically and laterally from non-cohesive to cohesive, and had multiple layers of organics. -

Measuring Knickpoint Migration in Ravine Z, Seven

Measuring Knickpoint Migration in Ravine Z, Seven Mile Creek Park, Nicollet County, MN By Michael Dickens A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Geology) at Gustavus Adolphus College 2015 Measuring Knickpoint Migration in Ravine Z, Seven Mile Creek Park, Nicollet County, MN By Michael Dickens Under the supervision of Laura Triplett Abstract The Minnesota River is facing increasing sediment loads, which are a result of sediment erosion in the rivers watershed. Likely sources for that sediment include upland topsoil, incising and head-cutting ravines, Bluffs and streambanks. The focus of this study is ravines, which are poorly understood in terms of erosional processes. One main way that ravines erode is through knickpoint migration, which happens as water flows over a tougher material, and falls onto a softer material, creating a back-cutting and over-steepening effect at the toe of the knickpoint. Material from the Bottom of the ravine is thus moBilized, and can be transported down the ravine into the Minnesota River. To help decipher the role of knickpoint migration in sediment loading on the Minnesota River, we examined a single ravine and its knickpoints over a span of several years. Seven Mile Creek, a tributary to the Minnesota River in Nicollet County, is an ideal location to study the factors that contribute to knickpoint migration. Ravine Z, a prominent ravine in Seven Mile Creek Park, Nicollet County, MN, is a very active eroding channel that is largely fed By farm drainage tiles. A digital elevation model and surveying tools were used to make a series of slope profiles spanning the period 2007-2014.