Is Mass Incarceration History?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOTO-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (1.424Mb)

CHICAN@ SOCIOGENICS, CHICAN@ LOGICS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHICAN@ PHILOSOPHY: RUPTURING THE BLACK-WHITE BINARY AND WESTERN ANTI-LATIN@ LOGIC A Dissertation by ANDREW CHRISTOPHER SOTO Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Tommy Curry Committee Members, Gregory Pappas Amir Jaima Marlon James Head of Department, Theodore George May 2018 Major Subject: Philosophy Copyright 2018 Andrew Christopher Soto ABSTRACT The aim of this project is to create a conceptual blueprint for a Chican@ philosophy. I argue that the creation of a Chican@ philosophy is paramount to liberating Chican@s from the imperial and colonial grip of the Western world and their placement in a Black-white racial binary paradigm. Advancing the philosophical and legal insight of Critical Race Theorists and LatCrit scholars Richard Delgado and Juan Perea, I show that Chican@s are physically, psychologically and institutionally threatened and forced by gring@s to assimilate and adopt a racist Western system of reason and logic that frames U.S. institutions within a Black-white racial binary where Chican@s are either analogized to Black suffering and their historical predicaments with gring@s or placed in a netherworld. In the netherworld, Chican@s are legally, politically and socially constructed as gring@s to uphold the Black-white binary and used as pawns to meet the interests of racist gring@s. Placing Richard Delgado and Juan Perea’s work in conversation with pioneering Chican@ intellectuals Octavio I. Romano-V, Nicolas C. -

Asha Smith Facesbyasha.Com

ASHA SMITH FACESBYASHA.COM MAKEUP ARTIST https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0999923 646.431.4728 SELECTED WORK EXPERIENCE (All Positions in New York City or Vicinity) Most Recent Experience Corporate Promotion: Ralph Lauren Fragrances Valdesiga Productions, LLC Makeup and Hair, June 2019 Conde Nast – Vanity Fair: Movies in Motion HMU/Grooming (Choreographers) Content can be viewed here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LZJy2cBlho8&t=1s May 2019 Live Television Comedy Special/Jose Cuervo Promotional: Comedy Central “Comedy Commune” Pudding Boy Productions Grooming for Matteo Lane, May 2019 Commercial: Housing Works (Non-Profit) Foxwood Productions Makeup and Hair, May 2019 Television Series: “Wrongman” – Season 2 (Starz Network) Radical Media Makeup and Hair, April 2019 Film (Short): Daughters of Solanas Women’s Weekend Film Challenge Director: Angelle Cooper Makeup and Hair, April 2019 Film “All the Little Things We Kill” (Feature), Director: Adam Neutzsky-Wulff Makeup and Hair, March 2018 “The Incredible Jessica James", (Feature), Director: Jim Sprouse Key Hair Stylist [Day player], August 2016 “Heavy Objects” (Feature), Director: Fletcher Crossman Makeup Department Supervisor, June - August 2014 Television Television Series: TBS “Search Party” Production Company: Gangway Films Key Makeup and Hair, September 2017 ASHA SMITH RESUME PAGE 2 Television con’d Television Promo/Commercial: Viacom MTV 2017 VMAs /”Extra Gum,” Production Company: New Creative Mix Makeup and Hair August & July 2017 Television Series - Client: The Food Network, “Worst Cooks -

Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth Into Relations with Land, Community, and Success

Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success By Theresa Amalia Stone A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair Professor Zeus Leonardo Professor Charles Briggs Summer 2019 Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success @2019 By Theresa Amalia Stone 1 Abstract Emplacing White Possessive Logics: Socializing Latinx Youth into Relations with Land, Community, and Success by Theresa Amalia Stone Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Patricia Baquedano-López, Chair This dissertation examines the logics and relations that Latinx youth are socialized into via a college preparation program from a settler colonial studies perspective. An ethnographic project drawing upon critical place inquiry and language socialization approaches, it features data from pláticas and interviews, participant observation, and a multi-sited place project, building upon youths’ and educators’ readings and navigations of their social worlds. It contends that white possessive logics (Moreton- Robinson, 2015) were enacted through a series of classificatory technologies of control which shifted in response to efforts by local educators to employ educational structures and practices that countered them. Further, it examines the navigation of the settler- native-slave triad by Latinx youth, as their status as exogenous others positioned them as not-quite-yet determined within this structure. This dissertation argues that the precarity and tenuousness of life shaped by racialized and gendered vulnerabilities made aspiring towards normative visions of success a (non)option for those given the opportunity to do so. -

AFS Year 7 Slate MASTER

AFS YEAR 7 FILM SLATE "1 AFS 2018-2019 FILM THEMES *Please note that this thematic breakdown includes documentary features, documentary shorts, animated shorts and episodic documentaries American Arts & Culture Entrepreneurism Chasing Trane! Blood, Sweat & Beer! Gentlemen of Vision! Chef Flynn! Honky Tonk Heaven: Legend of the Dealt! Broken Spoke! Ella Brennan: Commanding the Table! Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings Good Fortune! More Art Upstairs! Knife Skills! Moving Stories! New Chefs on the Block! Obit! One Hundred Thousand Beating Hearts! Restless Creature: Wendy Whelan! Human Rights Score: A Film Music Documentary! STEP! A Shot in the Dark! All-American Family! Disability Rights Bending the Arc! A Shot in the Dark! Cradle! All-American Family! Edith + Eddie! Cradle! I Am Jane Doe! Dealt! The Prosecutors! I’ll Push You! Unrest! Pick of the Litter! LGBTQI Reengineering Sam! Served Like a Girl! In A Heartbeat! Unrest! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Stumped# About Suicide! Stumped! "2 Mental Health Awareness Sports Cradle! A Shot in the Dark! Served Like a Girl! All-American Family! The S Word: Opening the Conversation Baltimore Boys! About Suicide! Born to Lead: The Sal Aunese Story! The Work! Boston: The Documentary! Unrest! Down The Fence! We Breathe Again! Run Mama Run! Skid Row Marathon! The Natural World and Space Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird A Plastic Ocean! Hamilton Above and Beyond: NASA’s Journey to STEM Tomorrow! Frans Lanting: The Evolution of Life! Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story! Mosquito! Dream Big: -

The Puzzling Neglect of Hispanic Americans in Research on Police–Citizen Relations Ronald Weitzer Published Online: 08 May 2013

This article was downloaded by: [George Washington University] On: 27 August 2014, At: 14:00 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ethnic and Racial Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 The puzzling neglect of Hispanic Americans in research on police–citizen relations Ronald Weitzer Published online: 08 May 2013. To cite this article: Ronald Weitzer (2014) The puzzling neglect of Hispanic Americans in research on police–citizen relations, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 37:11, 1995-2013, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2013.790984 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.790984 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Low-Income Black Mothers Parenting Adolescents in the Mass Incarceration Era: the Long Reach of Criminalization

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122419833386American Sociological ReviewElliott and Reid 833386research-article2019 American Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 84(2) 197 –219 Low-Income Black Mothers © American Sociological Association 2019 https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419833386DOI: 10.1177/0003122419833386 Parenting Adolescents in the journals.sagepub.com/home/asr Mass Incarceration Era: The Long Reach of Criminalization Sinikka Elliotta and Megan Reidb Abstract Punitive and disciplinary forms of governance disproportionately target low-income Black Americans for surveillance and punishment, and research finds far-reaching consequences of such criminalization. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 46 low-income Black mothers of adolescents in urban neighborhoods, this article advances understanding of the long reach of criminalization by examining the intersection of two related areas of inquiry: the criminalization of Black youth and the institutional scrutiny and punitive treatment of Black mothers. Findings demonstrate that poor Black mothers calibrate their parenting strategies not only to fears that their children will be criminalized by mainstream institutions and the police, but also to concerns that they themselves will be criminalized as bad mothers who could lose their parenting rights. We develop the concept of “family criminalization” to explain the intertwining of Black mothers’ and children’s vulnerability to institutional surveillance and punishment. We argue that to fully grasp the causes and consequences of mass incarceration and its disproportionate impact on Black youth and adults, sociologists must be attuned to family dynamics and linkages as important to how criminalization unfolds in the lives of Black Americans. Keywords criminalization, mothering, racism, adolescence, mass incarceration Punitive and disciplinary governance struc- Perry 2016; Rios 2011; Shedd 2015; Skiba tures the everyday lives of low-income Black et al. -

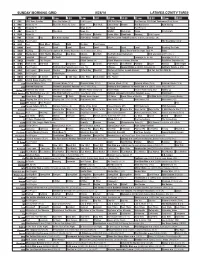

Sunday Morning Grid 8/28/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/28/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PBR Bull Riding The Barclays 2016 Golf Tournament Final Round. 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Ruff-Ruff, Chica Show Noodle Red Bull Series Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) Wildlife Rock-Park Tennis 2016 LLWS 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday FOX College Football NFL Preseason Football Chargers at Minnesota Vikings. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Dead Zone ››› 18 KSCI Paid Mom Mkver Church Faith Dr. John Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Breaking The Code 24 KVCR Healing The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. (TVG) Super Brain With Dr. Rudy Tanzi Å Yakov 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ The Truth About Retirement ADD and Loving It?! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage The Toy Job. Leverage (TV14) Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Belgian Grand Prix. -

The Relationship Between the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF THE AMERICAS AND THE HORSE: DECONSTRUCTING A EUROCENTRIC MYTH By Yvette Running Horse Collin A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies University of Alaska Fairbanks May 2017 © 2017 Yvette Running Horse Collin APPROVED: Raymond Barnhardt, Ph.D., Committee Chair Beth Ginondidoy Leonard, Ph.D., Committee Co-Chair Theresa Arevgaq John, Ph.D., Committee Member Marco A. Oviedo, Ph.D., Committee Member Michael Koskey, Ph.D., Department Chair Todd Sherman, M.F.A., Dean, College of Liberal Arts Michael Castellini, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate School Abstract This research project seeks to deconstruct the history of the horse in the Americas and its relationship with the Indigenous Peoples of these same lands. Although Western academia admits that the horse originated in the Americas, it claims that the horse became extinct in these continents during the Last Glacial Maximum (between roughly 13,000 and 11,000 years ago). This version of “history” credits Spanish conquistadors and other early European explorers with reintroducing the horse to the Americas and to her Indigenous Peoples. However, many Native Nations state that “they always had the horse” and that they had well established horse cultures long before the arrival of the Spanish. To date, “history” has been written by Western academia to reflect a Eurocentric and colonial paradigm. The traditional knowledge (TK) of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, and any information that is contrary to the accepted Western academic view, has been generally disregarded, purposefully excluded, or reconfigured to fit the accepted academic paradigm. -

Labeling Effects of First Juvenile Arrests: Secondary Deviance and Secondary Sanctioning∗

LABELING EFFECTS OF FIRST JUVENILE ARRESTS: SECONDARY DEVIANCE AND SECONDARY SANCTIONING∗ AKIVA M. LIBERMAN,1 DAVID S. KIRK,2 and KIM KIDEUK1 1Justice Policy Center, Urban Institute 2Department of Sociology, The University of Texas at Austin KEYWORDS: labeling, delinquency, arrest A growing literature suggests that juvenile arrests perpetuate offending and increase the likelihood of future arrests. The effect on subsequent arrests is generally regarded as a product of the perpetuation of criminal offending. However, increased rearrest also may reflect differential law enforcement behavior. Using longitudinal data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) together with official arrest records, the current study estimates the effects of first arrests on both reoffending and rearrest. Propensity score methods were used to control dif- ferences between arrestees and nonarrestees and to minimize selection bias. Among 1,249 PHDCN youths, 58 individuals were first arrested during the study period; 43 of these arrestees were successfully matched to 126 control cases that were equivalent on a broad set of individual, family, peer, and neighborhood factors. We find that first arrests increased the likelihood of both subsequent offending and subsequent ar- rest, through separate processes. The effects on rearrest are substantially greater and are largely independent of the effects on reoffending, which suggests that labels trig- ger “secondary sanctioning” processes distinct from secondary deviance processes. At- tempts to ameliorate deleterious labeling effects should include efforts to dampen their escalating punitive effects on societal responses. The 1980s and the early 1990s were characterized by an “epidemic” of youth violence in the United States, which peaked in 1993–1994 (Cook and Laub, 2002). -

Keep Trucha: a Condemnation Project for Chicana/O Youth

- CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY SAN MARCOS THESIS SIGNATURE PAGE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGICAL PRACTICE TI IESIS TITLE: Keep Trucha: Commendation Project for Chicana/o Youth. A UTI-lOR: Jose Stalin Plascencia-Castillo DATE Or SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE: 05/05/2016 THE THESIS liAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE THESIS COMMITTEE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIOLOGICAL PRACTICE. 5· 5·/~ DATE 5' -5-[ 0 DATE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY OF SAN MARCOS Keep Trucha: Condemnation Project for Chicana/o Youth A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree Masters of Art in Sociological Practice by Jose Stalin Plascencia-Castillo Committee in charge: Dr. Juan (Xuan) Santos Dr. Christopher Bickel Dr. Karen S. Glover May 2016 1 Keep Trucha: A Condemnation Project for Chicana/o Youth Copyright © 2016 by Jose Stalin Plascencia-Castillo 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER PAGE………………………………………………………………1 COPYRIGHT PAGE……………………………………………………...…2 TABLE OF CONTENTS …………………………………………………3-4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………...5-6 ABSTRACT……………………………………………………….………...7 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………….8-9 STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM……………………………….…10-11 SECTION ONE………………………………………………………..11-19 Literature Review……………………………………………………11 Hyper-criminality and Hyper-surveillance……………...…...11-12 The Youth Control Complex…………………………..…12-13 Identity Formation: Resisting and Conforming to the YCC……13-15 Inequality through Criminalization and Resistance……………15-16 -

Robert Andrew Leonard, Ph.D., Linguist Forensic Expert Witness in Linguistics and Language Hofstra University Professor of Lingu

Robert Andrew Leonard, Ph.D., Linguist Forensic Expert Witness in Linguistics and Language Hofstra University Professor of Linguistics Director, Institute for Forensic Linguistics, Threat Assessment and Strategic Analysis and Forensic Linguistics Capital Case Innocence Project Director, Graduate Program in Linguistics: Forensic Linguistics tel.: (516) 477-3834 fax: (516) 629-6027 email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.robertleonardassociates.com http://www.hofstra.edu/academics/colleges/hclas/cll/linguistics/ma-forensic-linguistics/ June 1, 2017 Contents: EXPERT WITNESS EDUCATION OTHER TRAINING ACADEMIC FELLOWSHIPS, AWARDS FOREIGN LANGUAGES LINGUISTIC CONSULTING MEDIA ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE EDITORSHIPS PUBLICATIONS – LINGUISTICS and SEMIOTICS PROFESSIONAL EVALUATION PANELS INVITED AND REFEREED PRESENTATIONS—LINGUISTICS and SEMIOTICS PRESENTATIONS –COMMUNICATION ACROSS CULTURES PRESENTATIONS –INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS BUSINESS-RELATED EXPERIENCE COURSES DEVELOPED AT HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY—Undergraduate; Graduate EXPERT WITNESS IN LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE Qualified as an Expert in Linguistics, under Frye and under Daubert in 12 States, 6 Federal Districts: in State Courts in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Nevada, and Pennsylvania, and in U.S. District Courts in Newark, NJ, Austin, TX, New York, NY, San Jose, CA, Tampa, FL, and Denver, CO. Testified as a linguistic expert before World Bank ICSID Tribunals in Washington, -

Toronto, the Great

SATURDAY, JULY 19, 2014 Scientists name Puerto Rico water mite after JLo Pop singer singer Jennifer Lopez op singer Jennifer Lopez may be thinking life is fun- ny after a group of scientists named a water mite in Albanian artist Saimir Strati places plastic straws in his latest environmen- Pher honor after discovering a new species near tal-themed mosaic “Save the earth” featuring the bitten apple of the Puerto Rico. The music of the Bronx, New York-born enter- Garden of Eden in Fier on July 17, 2014. Strati will be using over 180,000 tainer who has Puerto Rican roots was a hit with the group straws to complete the 30 square meter art piece. A multiple Guinness while they wrote about their findings, biologist Vladimir record holder with his previous mosaic pieces made among others things Pesic said in an email Wednesday. of nails, toothpicks and CDs, Strati has chosen recyclable materials for “The reason behind the unusual choice of name for the what he calls his postcard to the planet to show more care about the world new species is ... simple: J.Lo’s songs and videos kept the we all live in. — AFP photos team in a continuous good mood when writing the manu- script and watching World Cup Soccer 2014,” said Pesic, who works at the University of Montenegro. Pesic calls it a small token of gratitude for the singer of hits such as “Ain’t Trip Tips: Toronto, the Great It Funny,” “I Luh Ya Papi” and his personal favorite, “All I Have.” He’s the corresponding author of the study that was published Tuesday in the peer-reviewed online journal White North’s summer surprise ZooKeys.