Indicators for Disaster Risk Management OPERATION ATN/JF-7907-RG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoting Disaster Risk Reduction to Save Lives and Reduce Its Impacts WHO WE ARE

Photo: GTZ Promoting Disaster Risk Reduction to save lives and reduce its impacts WHO WE ARE he International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR) is a strategic framework adopted by United Nations Member States in 2000. The ISDR guides and coordinates theT efforts of a wide range of partners to achieve a substantive reduction in disaster losses. It aims to build resilient nations and communities as an essential condition for sustainable development. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) is the secretariat of the ISDR system. The ISDR system comprises numerous organizations, States, intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations, financial institutions, technical bodies and civil society, which work together and share information to reduce disaster risk. UNISDR serves as the focal point for the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) – a ten year plan of action adopted in 2005 by 168 governments to protect lives and livelihoods against disasters. Photo: Jean P. Lavoie Disaster Risk Reduction Communities will always face natural hazards. Current disasters, however, are often a direct result of, or are exacerbated by, human activities. Such activities are changing the Earth’s natural balance, interfering like never before with the atmosphere, oceans, polar caps, forest cover and biodiversity, as well as other natural resources which make our world a habitable place. Furthermore, we are also putting ourselves at risk in ways that are less visible. Because natural hazards can affect anybody, disaster risk reduction is everybody’s responsibility. Disasters are not natural and can often be prevented. Economic resources, political will and a shared sense of hope form part of our collective protection from calamities. -

Natural Hazards Predictions Name: ______Teacher: ______PD:___ 2

1 Unit 7: Earth’s Natural Hazards Lesson 1: Natural Hazards Lesson 2: Natural Hazards Predictions Name: ___________________ Teacher: ____________PD:___ 2 Unit 7: Lesson 1 Vocabulary 3 1 Natural Hazard: 2 Natural Disaster: 3 Volcano: 4 Volcanic Eruption: 5 Active Volcano: 6 Dormant Volcano: 7 Tsunami: 8 Tornado: 4 WHY IT MATTERS! Here are some questions to consider as you work through the unit. Can you answer any of the questions now? Revisit these questions at the end of the unit to apply what you discover. Questions: Notes: What types of natural hazards are likely where you live? How could the natural hazards you listed above cause damage or injury? What is a natural disaster? What types of monitoring and communication networks alert you to possible natural hazards? How could your home and school be affected by a natural hazard? How can the effects of a natural disaster be reduced? Unit Starter: Analyzing the Frequency of Wildfires 5 Analyzing the Frequency of Wildfires Choose the correct phrases to complete the statements below: Between 1970 and 1990, on average fewer than / more than 5 million acres burned in wildfires each year. Between 2000 and 2015, more than 5 million / 10 million acres burned in more than half of the years. Overall, the number of acres burned each year has been increasing / decreasing since 1970. 6 Lesson 1: Natural Hazards In 2015, this wildfire near Clear Lake, California, destroyed property and devastated the environment. Can You Explain it? In the 1700s, scientists in Italy discovered a city that had been buried for over 1,900 years. -

Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa

Natural Disasters in Public Disclosure Authorized the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2014 Urban, Social Development, and Disaster Risk Management Unit Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Natural Disasters in the Middle East and North Africa: A Regional Overview © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundar- ies, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorse- ment or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Recon- struction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

Thematic Sheet on Disaster Risk Reduction

H E T E M R E A T H I P C S 2 S H E E T Disaster Risk Reduction Sphere Thematic Sheets (TS) explain Sphere’s relevance for a specific theme. Here, we encourage Sphere users to mainstream Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) into their work and highlight to DRR specialists how Sphere supports their work. The Sphere Handbook does not explicitly mention DRR in its principles and standards. However, there is a direct and strong link between the two. This TS gives a brief overview of the concept of DRR and explores the mutual relevance of Sphere and DRR activities, common principles and approaches anchored in both, as well as a focus on Sphere’s technical chapters. The document is complemented by further online content. Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction in Emergency Response While Sphere standards focus on the disaster response phase, they need to be solidly anchored and integrated in prevention, mitigation, preparedness, and recovery activities: “Relief aid must strive to reduce future vulnerabilities to disaster as well as meeting basic needs” (NGO Code of Conduct, Principle 8) Definition:Disaster risk reduction (DRR) is the concept and practice of reducing the risk of disaster through systematic efforts to analyse and manage causal factors. It includes reducing exposure to hazards, lessening the vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improving preparedness for adverse events (Sphere definition of DRR). This implies the following key elements of DRR*: (1) Analysis of risks, vulnerabilities and capacities, (2) Reduction of exposure, (3) Reduction of vulnerabilities and (4) Enhancing capacities *please see online glossary for definitions of various DRR-related terms used in this TS Disasters related with natural hazards are increasing The SFDRR also highlights the need to mainstream in frequency and intensity, many of them exacerbated disaster risk reduction in the full disaster management by climate change. -

Roots for Resilience: a Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region

Roots for Resilience: Resilience: for Roots A Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region of Risk Profile Emergency A Health Trees, a symbol of resilience The book uses the tree of life, which is an archetypal central theme across all cultures, including in the This book provides a well-researched, WHO South-East Asia Region. The tree is therefore documented and illustrated analysis of a symbol of resilience with its well-entrenched and risks, threats, vulnerabilities and coping nourished roots. It survives wars, pandemics and capacities in the event of disasters, catastrophes while continuing to grow, shoot new epidemics and other calamities in the leaves and bear fruit. countries of the WHO South-East Roots for Resilience Asia Region. The oak tree used on the cover is known to be sturdy and resilient. Different tree motifs are used as These risks are then analysed through separators. The pine tree is rooted at high altitudes the lens of health status and capacity for but survives extremities of climate. Similarly, A Health Emergency Risk Profile emergency management across several mangroves can resist floods and bamboo does not hazards. The book aims to draw up break easily even with strong winds. The use of of the South-East Asia Region action points and recommendations to roots elsewhere reiterates the need to strengthen the address these risks in the immediate-, fundamentals—health systems, health workforce, medium- and long term, especially at the infrastructure and capacities for health emergency subnational level. risk management. Roots for Resilience A Health Emergency Risk Profile of the South-East Asia Region Roots for resilience: a health emergency risk profile of the South-East Asia Region ISBN 978-92-9022-609-3 © World Health Organization 2017 Some rights reserved. -

HAZARD MITIGATION for NATURAL DISASTERS a Starter Guide for Water and Wastewater Utilities

HAZARD MITIGATION FOR NATURAL DISASTERS A Starter Guide for Water and Wastewater Utilities Select a menu option below. New users should start with Overview Hazard Mitigation. Overview Join Local Mitigation Develop Mitigation Implement and Mitigation Case Study Hazard Mitigation Efforts Projects Fund Project Overview Overview - Hazard Mitigation Hazard Mitigation Join Local Hazards Posed by Natural Disasters Mitigation Efforts Water and wastewater utilities are vulnerable to a variety of hazards including natural disasters such as earthquakes, flooding, tornados, and Develop wildfires. For utilities, the impacts from these hazard events include Mitigation Projects damaged equipment, loss of power, disruptions to service, and revenue losses. Why Mitigate the Hazards? Implement and Fund Project It is more cost-effective to mitigate the risks from natural disasters than it is to repair damage after the disaster. Hazard mitigation refers to any action or project that reduces the effects of future disasters. Utilities can Mitigation implement mitigation projects to better withstand and rapidly recover Case Study from hazard events (e.g., flooding, earthquake), thereby increasing their overall resilience. Mitigation projects could include: • Elevation of electrical panels at a lift station to prevent flooding damage. • Replacement of piping with flexible joints to prevent earthquake damage. • Reinforcement of water towers to prevent tornado damage. Mitigation measures require financial investment by the utility; however, mitigation could prevent more costly future damage and improve the reliability of service during a disaster. Disclaimer: This Guide provides practical solutions to help water and wastewater utilities mitigate the effects of natural disasters. This Guide is not intended to serve as regulatory guidance. Mention of trade names, products or services does not convey official U.S. -

Natural Hazards Mitigation Planning: a Community Guide

Natural A step-by-step guide Hazards to help Massachusetts communities deal with Mitigation multiple natural Planning: hazards and A Community to minimize Guide future losses Prepared by With assistance from Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management Federal Emergency Management Agency Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency Natural Resources Conservation Service Massachusetts Hazard Mitigation Team January 2003 Mitt Romney, Governor · Peter C. Webber, DEM Commissioner · Stephen J. McGrail, MEMA Director P r e f a c e The original version of this workbook was disaster mitigation program, the Flood Mitigation published in 1997 and entitled, Flood Hazard Assistance (FMA) program, as well as other federal, Mitigation Planning: A Community Guide. Its state and private funding sources. purpose was to serve as a guide for the preparation Although the Commonwealth of of a streamlined, cost-efficient flood mitigation plan Massachusetts has had a statewide Hazard by local governments and citizen groups. Although Mitigation Plan in place since 1986, there has been the main purpose of this revised workbook has not little opportunity for community participation and changed from its original mission, this version has input in the planning process to minimize future been updated to encompass all natural hazards and disaster damages. A secondary goal of the to assist Massachusetts’ communities in complying workbook is to encourage the development of with the all hazards mitigation planning community-based plans and obtain local input into requirements under the federal Disaster Mitigation Massachusetts’ state mitigation planning efforts in Act of 2000 (DMA 2000). The parts of this order to improve the state’s capability to plan for workbook that correspond with the requirements of disasters and recover from damages. -

Issue Brief: Disaster Risk Governance Crisis Prevention and Recovery

ISSUE BRIEF: DISASTER RISK GOVERNANCE CRISIS PREVENTION AND RECOVERY United Nations Development Programme “The earthquake in Haiti in January 2010 was about the same magnitude as the February 2011 earthquake in Christchurch, but the human toll was significantly higher. The loss of 185 lives in Christchurch was 185 too many. However, compared with the estimated 220,000 plus killed in Haiti in 2010, it becomes evident that it is not the magnitude of the natural hazard alone that determines its impact.” – Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator Poorly managed economic growth, combined with climate variability and change, is driving an overall rise in global disaster Around the world, it is the poor who face the greatest risk from risk for all countries. disasters. Those affected by poverty are more likely to live in drought and flood prone regions, and natural hazards are far Human development and disaster risk are interlinked. Rapid more likely to hurt poor communities than rich ones. economic and urban development can lead to growing Ninety-five percent of the 1.3 million people killed and the 4.4 concentrations of people in areas that are prone to natural billion affected by disasters in the last two decades lived in developing countries, and fewer than two per cent of global hazards. The risk increases if the exposure of people and assets deaths from cyclones occur in countries with high levels of to natural hazards grows faster than the ability of countries to development. improve their risk reduction capacity. DISASTER RISK REDUCTION AND GOVERNANCE In the context of risk management, this requires that the general public are sufficiently informed of the natural hazard risks they are exposed to and able to take necessary The catastrophic impact of disasters is not ‘natural.’ Disasters are precautions. -

Disaster Risk-Informed and Resilient Covid-19 Recovery

DISASTER RISK-INFORMED AND RESILIENT COVID-19 RECOVERY Virtual Side Event at the 75 th Session of the General Assembly Second Committee 3pm-5pm EDT – Thursday 15 October 2020 Organized by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) in collaboration with the International Labour Organization (ILO), the Office of the High Representative for LDCs, LLDCs and SIDS (OHRLLS), and UN Women CONCEPT NOTE SETTING THE SCENE Today’s risk landscape is rapidly changing, and risk has become progressively more systemic. New interactions between environmental, economic, technological and biological risks are emerging in ways that were not anticipated. One hazard can trigger another with cascading impacts across systems and borders and devastating impacts on progress across the SDGs. However, policies, institutions and financing remain focused on preparing for and responding to disasters, rather than preventing the creation of risk and subsequent losses. To achieve the SDGs, current, emerging and future risks need to be considered in policy and investment decisions in all sectors. The COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis exemplify the systemic nature of risk and the potential for cascading impacts. COVID-19 has triggered an unprecedented social and economic catastrophe on a global scale. Decades of development progress have unraveled, and poverty and inequality, particularly gender inequality, have deepened. As a consequence, vulnerability and exposure to other hazards, including the intensifying climate crisis, have greatly increased with impacts foreseen long into the future. While these hazards and risks affect all countries, the poorest and most exposed and vulnerable people, communities and countries bear the brunt. Despite strong commitment to disaster risk reduction, LDCs, LLDCs, and SIDS continue to suffer disproportionately high losses in human and economic terms owing to disasters. -

Volcanic Hazards As Components of Complex Systems: the Case of Japan

Volume 13 | Issue 33 | Number 6 | Article ID 4359 | Aug 17, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volcanic Hazards as Components of Complex Systems: The Case of Japan Gregory Smits The past year or so has been a time of the earth’s crust suggested Mt. Fuji is more particularly vigorous volcanic activity in Japan, likely to erupt owing to effects from the 2011 or at least activity that has intruded into public Tōhoku earthquake.3 Well publicized by a press awareness. Perhaps most dramatic was the release on the eve of its publication, mass deadly eruption of Mt. Ontake on September media around the world have reported this 27, 2014, whose 57 fatalities were the first finding, along with speculation regarding volcano-related deaths in Japan since 1991. On possible connections between earthquakes and May 29, 2015, Mt. Shindake, off the southern volcanic eruptions. tip of Kyushu, erupted violently, forcing the evacuation of the island of Kuchinoerabu. That As of June 30, 2015, the Japan Meteorological same day, Sakurajima, located just north in Agency (JMA) designated ten volcanoes in or Kagoshima Bay, erupted more forcefully than near the main Japanese islands as warranting usual. Sakurajima has been erupting in some levels of warning ranging from Mt. Shindake’s fashion almost continuously since 1955, but Level 5 (“Evacuate”), to Level 2 (“Do not since 2006, its activity has become relatively approach the crater”) in seven cases. more vigorous. Indeed, a May 30 Asahi shinbun Sakurajima is at Level 3 (“Do not approach the article characterized these eruptions as “the volcano”), as is Hakoneyama, located near Mt. -

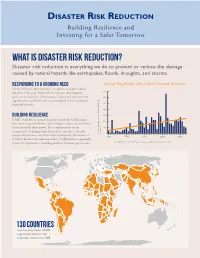

Disaster Risk Reduction Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow

DISASTER RISK REDUCTION Building Resilience and Investing for a Safer Tomorrow What is Disaster Risk Reduction? Disaster risk reduction is everything we do to prevent or reduce the damage caused by natural hazards like earthquakes, floods, droughts, and storms. Responding to a Growing Need Global Population Affected by Natural Disasters Natural disasters affect hundreds of millions of people around 700 the globe every year. With each new disaster, development gains are threatened as infrastructure is destroyed and economic 600 opportunities and livelihoods are interrupted or lost, leading to increased poverty. 500 400 Building Resilience 300 USAID responds to natural disasters around the world, saving 200 lives, protecting livelihoods, and working to reduce the economic losses caused by these events. Just as importantly, we are 100 committed to helping people lessen their exposure to hazards, Reported Number of People Affected Affected Reported Number of People (in Millions) 0 prepare for disasters, and better withstand shocks. The lessons of 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 USAID’s disaster risk reduction efforts worldwide have repeatedly shown the importance of building resilience in hazard-prone areas. Source: EM-DAT - The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, www.emdat.be, April 2014 130 COUNTRIES have benefited from USAID- supported disaster risk reduction efforts since 1989. USAID’S DISASTER RISK REDUCTION PROGRAMS SAVE LIVES Strengthening Early Warning Since 1989, we have helped establish 17 global, regional, or national early warning systems for drought, volcanoes, cyclones, and floods. These early warning systems work. For example, in 2013, warnings issued days prior to Cyclone Phailin’s arrival in India gave local authorities time to coordinate preparedness measures, including the evacuation of 1 million people living in coastal areas. -

Earthquakes That Trigger Other Natural Hazards

Chain Reaction: Earthquakes that Trigger Other Natural Hazards Compiled by Diane Noserale and Tania Larson volcanic eruptions. concave structure called a “caldera.” These structures are Scientists have known that movement of magma often found around the world. Yellowstone and Crater Lake fi re destroys much of a major city. The side triggers earthquakes, but they are discovering that this are two examples in the United States. Research shows of a mountain collapses and then explodes. relationship may also work in reverse. Scientists are look- that activity at calderas often occurred within months or A train of waves sweeps away coastal vil- ing at earthquakes that meet very specifi c criteria: a mag- even hours of large regional earthquakes, sometimes as lages over thousands of miles. All of these nitude of 6 or higher; a location on major fault zones a precursor to the earthquakes and sometimes as a result events are disasters that have started with near a volcano; and a later eruption of a nearby volcano. of them. Aor been triggered by an earthquake. Some of the triggers They are fi nding evidence that these earthquakes might were among the largest earthquakes ever recorded. But have triggered the eruptions. Landslides the disasters that followed were often so large that the In the early morning of Nov. 29, 1975, a magnitude- Heavy rain, wildfi res, volcanic eruptions and human earthquakes were overshadowed, and so, we hear about 7.2 earthquake struck the Big Island of Hawaii. Less than activity often work together to cause landslides. In hilly the eruption of Mount St.