A Town Shaped by Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seaton Wetlands Sidmouth Seaton

How to find us © CROWN COPYRIGHT DATABASE RIGHTS 2012 ORDNANCE SURVEY 100023746 ORDNANCE SURVEY RIGHTS 2012 COPYRIGHT DATABASE © CROWN Lyme Regis Colyford Axe Estuary Axe Estuary WETLANDS WETLANDS A3052 Seaton Wetlands Sidmouth Seaton Seaton Road Wetlands Information Axe Estuary ENTRANCE Seaton Cemetery WETLANDS ◊ Free parking River Axe ◊ Toilets (including disabled toilet and baby changing) ◊ 5 bird hides Seaton Wetlands is located six miles west of ◊ Tramper off-road mobility scooter hire Lyme Regis and eight miles east of Sidmouth, ◊ Discovery hut between Colyford and Seaton. ◊ Picnic area In the middle of Colyford village on the A3052, take the Seaton road, signposted Axe Vale Static ◊ No dogs except assistance dogs Caravan Park. After half a mile turn left into ◊ Refreshments at weekends Seaton cemetery and continue through the ◊ Cycling welcomed on most of site cemetery car park to the Wetlands parking area. ◊ Wheelchair and buggy friendly paths ◊ Pond dipping equipment for hire Contact the countryside team: East Devon District Council ◊ Nearly 4 miles of trails/boardwalks Knowle Sidmouth EX10 8HL Tel: 01395 517557 Email: [email protected] www.eastdevon.gov.uk /eastdevoncountryside X2002 East Devon – an outstanding place Lyme Regis Colyford welcome to seaton wetlands N Swan Hill Road Sidmouth Entrance Popes Lane 1 Tram line Tram path Wheelchair friendly Footpath Colyford Seaton Road Common Hide 1 Water body Water Reserve Nature bed Reed colyford common Tidal salt marsh with broadwalk access to hide, viewing WC 2 platform and circular reedbed walk. Bus stop allowed Cyclists flooded area Seasonally Island Hide 3 Cemetery Entrance Marsh Lane Tower Hide Colyford Road Colyford 2 stafford marsh River Axe Ponds, reeds and the Stafford Brook make up the learning zone and wildlife garden. -

COPPLESTONE Via Crediton Stagecoach 5, 5C EXETER

EXETER - COPPLESTONE Via Crediton Stagecoach 5, 5C EXETER - COPPLESTONE Via Exeter St Davids, Crediton Stagecoach 5A, 5B Monday - Saturday (Except Public Holidays) 5 5 5B 5A 5 5 5A 5 5 5 5B 5B 5 5C 5C NS S NS S NS S S NS S NS S NS NS EXETER, Bus Station 0550 0620 0620 0650 0655 0700 0715 0740 0750 0800 0805 0815 0815 0830 0845 EXETER, St. Davids Station - - 0626 0658 - - 0723 - - - 0813 0823 - - - EXETER, West Garth Road top 0558 0628 0631 0704 0703 0708 0729 0749 0759 0810 0819 0829 0826 0841 0855 NEWTON ST CYRES, Crown & Sceptre 0608 0638 0638 0712 0713 0717 0738 0758 0808 0819 0829 0838 0835 0850 0904 CREDITON, Rail Station - - 0644 0718 - - 0744 - - - 0835 0844 - - - CREDITON, High Street Lloyds Bank 0614 0646 0648 0723 0721 0726 0749 0806 0816 0827 0839 0849 0843 0900 0912 CREDITON, Tuckers Close 0617 0650 - - 0725 0730 - 0810 0820 0831 - - 0847 - - COPPLESTONE, Stone - - 0656 0731 - 0757 - - - 0850 0857 - 0908 0920 Continues to: - - ND OK - - OK - - - ND ND - CH CH 5 5A 5 5C 5B 5 5C 5A 5 5C 5B 5 5C 5A 5 EXETER, Bus Station 0900 0915 0935 0955 1015 1035 1055 1115 1135 1155 1215 1235 1255 1315 1335 EXETER, St. Davids Station - 0923 - - 1023 - - 1123 - - 1223 - - 1323 - EXETER, West Garth Road top 0910 0929 0945 1005 1029 1045 1105 1129 1145 1205 1229 1245 1305 1329 1345 NEWTON ST CYRES, Crown & Sceptre 0919 0938 0954 1014 1038 1054 1114 1138 1154 1214 1238 1254 1314 1338 1354 CREDITON, Rail Station - 0944 - - 1044 - - 1144 - - 1244 - - 1344 CREDITON, High Street Lloyds Bank 0927 0949 1002 1022 1049 1102 1122 1149 1202 1222 1249 1302 1322 1349 1402 CREDITON, Tuckers Close 0931 - 1006 - - 1106 - - 1206 - - 1306 - - 1406 COPPLESTONE, Stone - 0957 - 1030 1057 - 1130 1157 - 1230 1257 - 1330 1357 - Continues to: - OK - CH ND - CH OK - CH ND - CH OK - 5C 5B 5 5C 5A 5A 5 5 5B 5 5C 5 5B 5C 5A NS S EXETER, Bus Station 1355 1415 1435 1455 1515 1515 1535 1555 1620 1635 1655 1715 1735 1750 1800 EXETER, St. -

River Axe Draft Restoration Plan

Restoring the River Axe Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation River Restoration Plan Draft for comment - 7 December 2015 to 17 January 2016 CONTENTS Chapter Page Executive Summary 1 Aim of the restoration plan 1 Working with others 2 How to comment on the draft plan 3 Delivering the restoration plan 3 1 Restoration of the River Axe 5 1.1 Introduction 5 1.2 The need for restoration 7 1.3 A restoration vision 7 1.4 How can we deliver this restoration? 8 1.5 Our approach 8 1.6 How to use this plan 10 1.7 Who is this plan for? 11 2 The River Axe Site of Special Scientific Interest 12 2.1 Geology and hydrology 12 2.2 Ecology 13 2.3 Conservation objectives for the River Axe SSSI 13 2.4 Condition of the River Axe SSSI 14 2.5 Water Framework Directive objectives 16 2.6 Land use and land use change 17 2.7 Water quality 17 2.8 Flood risk 18 2.9 Invasive non-native species and disease 19 2.10 Influences on geomorphology and channel change 20 3 River sector descriptions 23 3.1 Summary of sector descriptions 23 3.2 Upper sector 25 3.2.1 Physical characteristics 26 3.2.2 Historical change 26 3.2.3 Geomorphological behaviour 27 3.2.4 Significant issues 27 3.3 Mid sector 29 3.3.1 Physical characteristics 30 3.3.2 Historical change 30 3.3.3 Geomorphological behaviour 31 3.3.4 Significant issues 31 3.4 Lower sector 33 3.4.1 Physical characteristics 35 3.4.2 Historical change 35 3.4.3 Geomorphological behaviour 36 3.4.4 Significant issues 36 DRAFT FOR COMMENT 4 Channel modifications and restoration measures 38 4.1 Geomorphology -

South West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment

South West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment March 2016 Executive summary The Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) for the South West River Basin District (RBD) provides an overview of the range of flood risks from different sources across the 9 catchments of the RBD. The RBD catchments are defined in the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) and based on the natural configuration of bodies of water (rivers, estuaries, lakes etc.). The FRMP provides a range of objectives and programmes of measures identified to address risks from all flood sources. These are drawn from the many risk management authority plans already in place but also include a range of further strategic developments for the FRMP ‘cycle’ period of 2015 to 2021. The total numbers of measures for the South West RBD FRMP are reported under the following types of flood management action: Types of flood management measures % of RBD measures Prevention – e.g. land use policy, relocating people at risk etc. 21 % Protection – e.g. various forms of asset or property-based protection 54% Preparedness – e.g. awareness raising, forecasting and warnings 21% Recovery and review – e.g. the ‘after care’ from flood events 1% Other – any actions not able to be categorised yet 3% The purpose of the HRA is to report on the likely effects of the FRMP on the network of sites that are internationally designated for nature conservation (European sites), and the HRA has been carried out at the level of detail of the plan. Many measures do not have any expected physical effects on the ground, and have been screened out of consideration including most of the measures under the categories of Prevention, Preparedness, Recovery and Review. -

South West River Basin Management Plan, Including Local Development Documents and Sustainable Community Strategies (Local Authorities)

River Basin Management Plan South West River Basin District Contact us You can contact us in any of these ways: • email at [email protected] • phone on 08708 506506 • post to Environment Agency (South West Region), Manley House, Kestrel Way, Exeter EX2 7LQ The Environment Agency website holds the river basin management plans for England and Wales, and a range of other information about the environment, river basin management planning and the Water Framework Directive. www.environment-agency.gov.uk/wfd You can search maps for information related to this plan by using ‘What’s In Your Backyard’. http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/maps SW River Basin Management Plan Erratum The following changes were made to this document in January 2011. Table 1 updated to reflect reduction by two in number of heavily modified river water bodies and increase by two in number of natural river water bodies. Figure 15 for Tamar catchment updated to reflect change in two river water bodies from heavily modified to natural (see erratum sheet in Annex B for water body specific details). Published by: Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD tel: 08708 506506 email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency Some of the information used on the maps was created using information supplied by the Geological Survey and/or the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and/or the UK Hydrographic Office All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior -

Transport Information

TIVERTON www.bicton.ac.uk 1hr 30mins CULLOMPTON TRANSPORT TRANSPORT GUIDELINES 55mins - The cost for use of the daily transport for all non-residential students can be paid for per HONITON INFORMATION term or in one payment in the Autumn term to cover the whole year - Autumn, Spring & CREDITON 45mins Summer terms. 1hr 5mins AXMINSTER 1hr 10mins - No knives to be taken onto the contract buses or the college campus. - Bus passes will be issued on payment and must be available at all times for inspection. BICTON COLLEGE - Buses try to keep to the published times, please be patient if the bus is late it may have EXETER been held up by roadworks or a breakdown, etc. If you miss the bus you must make 30 - 45mins your own way to college or home. We will not be able to return for those left behind. - SEAT BELTS MUST BE WORN. DAWLISH LYME REGIS - All buses arrive at Bicton College campus by 9.00am. 1hr 25mins 1hr 20mins - Please ensure that you apply to Bicton College for transport. SIDMOUTH 15mins - PLEASE BE AT YOUR BUS STOP 10 MINUTES BEFORE YOUR DEPARTURE TIME. NEWTON ABBOT - Buses leave the campus at 5.00pm. 1hr SEATON 1hr - Unfortunately transport cannot be offered if attending extra curricular activities e.g. staying TEIGNMOUTH late for computer use, discos, late return from sports fixtures, equine duties or work 1hr 15mins experience placements. - Residential students can access the transport to go home at weekends by prior arrangement with the Transport Office. - Bicton College operates a no smoking policy in all of our vehicles. -

University Public Transport Map and Guide 2018

Fancy a trip to Dartmouth Plymouth Sidmouth Barnstaple Sampford Peverell Uffculme Why not the beach? The historic port of Dartmouth Why not visit the historic Take a trip to the seaside at Take a trip to North Devon’s Main Bus has a picturesque setting, maritime City of Plymouth. the historic Regency town main town, which claims to be There are lots of possibilities near Halberton Willand Services from being built on a steep wooded As well as a wide selection of of Sidmouth, located on the the oldest borough in England, try a day Exeter, and all are easy to get to valley overlooking the River shops including the renowned Jurassic Coast. Take a stroll having been granted its charter Cullompton by public transport: Tiverton Exeter Dart. The Pilgrim Fathers sailed Drakes Circus shopping centre, along the Esplanade, explore in 930. There’s a wide variety Copplestone out by bus? Bickleigh Exmouth – Trains run every from Dartmouth in 1620 and you can walk up to the Hoe the town or stroll around the of shops, while the traditional Bradninch There are lots of great places to half hour and Service 57 bus many historic buildings from for a great view over Plymouth Connaught Gardens. Pannier Market is well worth Crediton runs from Exeter Bus station to Broadclyst visit in Devon, so why not take this period remain, including Sound, visit the historic a visit. Ottery St Mary Exmouth, Monday to Saturday Dartmouth Castle, Agincourt Barbican, or take a trip to view Exeter a trip on the bus and enjoy the Airport every 15 mins, (daytime) and Newton St Cyres House and the Cherub Pub, the ships in Devonport. -

Cc100712cba Severe Weather Event 7Th July 2012

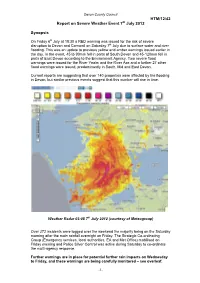

Devon County Council HTM/12/42 Report on Severe Weather Event 7 th July 2012 Synopsis On Friday 6 th July at 18:30 a RED warning was issued for the risk of severe disruption to Devon and Cornwall on Saturday 7 th July due to surface water and river flooding. This was an update to previous yellow and amber warnings issued earlier in the day. In the event, 45 to 90mm fell in parts of South Devon and 45-120mm fell in parts of East Devon according to the Environment Agency. Two severe flood warnings were issued for the River Yealm and the River Axe and a further 27 other flood warnings were issued, predominantly in South, Mid and East Devon. Current reports are suggesting that over 140 properties were affected by the flooding in Devon, but similar previous events suggest that this number will rise in time. Weather Radar 03:05 7 th July 2012 (courtesy of Meteogroup) Over 272 incidents were logged over the weekend the majority being on the Saturday morning after the main rainfall overnight on Friday. The Strategic Co-ordinating Group (Emergency services, local authorities, EA and Met Office) mobilised on Friday evening and Police Silver Control was active during Saturday to co-ordinate the multi-agency response. Further warnings are in place for potential further rain impacts on Wednesday to Friday, and these warnings are being carefully monitored – see overleaf. -1- Devon County Council DCC’s Flood Risk Management, Highways and Emergency Planning Teams are working closely with the District Councils and the Environment Agency to coordinate a full response. -

Download Annex A

Landscape Character Assessment in the Blackdown Hills AONB Landscape character describes the qualities and features that make a place distinctive. It can represent an area larger than the AONB or focus on a very specific location. The Blackdown Hills AONB displays a variety of landscape character within a relatively small, distinct area. These local variations in character within the AONB’s landscape are articulated through the Devon-wide Landscape Character Assessment (LCA), which describes the variations in character between different areas and types of landscape in the county and covers the entire AONB. www.devon.gov.uk/planning/planning-policies/landscape/devons-landscape-character- assessment What information does the Devon LCA contain? Devon has been divided into unique geographical areas sharing similar character and recognisable at different scales: 7 National Character Areas, broadly similar areas of landscape defined at a national scale by Natural England and named to an area recognisable on a national scale, for example, ‘Blackdowns’ and ‘Dartmoor’. There are 159 National Character Areas (NCA) in England; except for a very small area in the far west which falls into the Devon Redlands NCA, the Blackdown Hills AONB is within Blackdowns NCA. Further details: www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-character-area-profiles-data-for-local- decision-making/national-character-area-profiles#ncas-in-south-west-england 68 Devon Character Areas, unique, geographically-specific areas of landscape. Each Devon Character Area has an individual identity, but most comprise several different Landscape Character Types. Devon Character Areas are called by a specific place name, for example, ‘Blackdown Hills Scarp’ and ‘Axe Valley’. -

Issue 16, September 2012

News for staff and friends of NDHT Trust vision Incorporating community services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon We will deliver integrated health and social care to support people to live as healthily and independently as possible, recognising the differing needs of our local communities across Devon Issue 116,6 September 2012 Trust hospitals earn excellent ratings for food, environment and privacy HOSPITALS run by the Trust provide National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) North Devon District Hospital was rated excellent non-clinical services for on the back of its annual Patient as excellent in two categories and good patients, according to inspectors. Environment Action Team (PEAT) in the third, as were Crediton, Exeter assessments. Community Hospital (Whipton), Honiton Twelve of our 18 hospitals were rated as and Moretonhampstead. excellent in all three categories of food, Inspectors checked all acute and environment (including cleanliness) and community hospitals in England for Exmouth Hospital scored as excellent in privacy and dignity. their standards in non-clinical areas. one and good in the other two. The other six hospitals all achieved a In the Trust’s Northern region, the Hospitals rated as excellent are said to combination of excellent and good community hospitals at Bideford, consistently exceed expectations, with ratings in those three areas. Holsworthy, Ilfracombe, South Molton little if any room for improvement. and Torrington scored as excellent in The figures were published by the Those rated as good show a clear all three Environment Privacy and commitment to achieving and Site name Food score categories. score dignity score maintaining the highest possible Matt opens unit Axminster Hospital Excellent Excellent Excellent In the Eastern standards, with only limited room for Bideford Hospital Excellent Excellent Excellent area, there improvement. -

Underwood Underwood Church Lane, Newton St Cyres, Exeter, EX5 5BN Exeter 5 Miles Crediton 3.5 Miles

Underwood Underwood Church Lane, Newton St Cyres, Exeter, EX5 5BN Exeter 5 miles Crediton 3.5 miles • No onward chain • Elevated within a popular village • Detached 3 bedroom property with large garden • Planning permission for extension and alteration • Double garage & ample parking Offers in excess of £400,000 SITUATION Newton St Cyres has a strong community and a number of facilities including a fine church, primary school (Ofsted: Good), post office / general store and village inn. There is a railway station on the Tarka Line (Exeter to Barnstaple). The bustling market town of Crediton (3.5 miles) has a good number of independent shops together with banks, garages, post office and supermarkets as well as secondary schooling A detached property with planning permission to create a and a sports centre with indoor swimming pool. Five miles to the east lies the university and cathedral city of Exeter, which wonderful family home in a popular village has an impressive range of amenities befitting a centre of its importance including excellent shopping, dining, theatre and sporting and recreational pursuits. Exeter also has mainline railway stations on the Paddington and Waterloo lines and an international airport with daily flights to London. DESCRIPTION The property can be enjoyed as it stands, but there is scope for modernisation, and planning permission has already been granted for a substantial extension which could create a wonderful home. The current layout provides three bedrooms, two reception rooms, kitchen, bathroom, separate wc and en suite shower. ACCOMMODATION The entrance hall provides stairs to the first floor with storage beneath, a further storage cupboard and a cloakroom. -

Buses on Boxing Day Exeter Areas

Buses on Boxing Day Exeter Areas Exeter • Newton St Cyres • Crediton 5 26th December 2020 Exeter Paris St Stop 16 0820 then 20 1720 West Garth Road (Top) 0828 at 28 1728 Newton St Cyres 0836 these 36 until 1736 Crediton, Lloyds Bank 0844 times 44 1744 Crediton Westernlea 0848 each 48 1748 Crediton Tuckers Close arr 0849 hour 49 1749 Crediton • Newton St Cyres • Exeter 5 26th December 2020 Crediton Westernlea 0848 then 48 1748 Crediton Tuckers Close dep 0853 at 53 1753 Crediton, High Street 0857 these 57 until 1757 Newton St Cyres 0904 times 04 1804 West Garth Road (Top) 0913 each 13 1813 Exeter Paris St Stop 16 0923 hour 23 1823 Exeter • Topsham • Exmouth • Brixington 57 26th December 2020 Exeter Sidwell St stop 19 0840 0910 40 10 1640 1710 1740 RDE Hospital Barrack Road 0845 0915 then 45 15 1645 1715 1745 Topsham The Nelson 0856 0926 at 56 26 1656 1726 1756 Lympstone Saddlers Arms 0906 0936 these 06 36 until 1706 1736 1806 Exmouth Parade arr 0915 0945 times 15 45 1715 1745 1815 Exmouth Parade arr 0918 0948 each 18 48 1718 1748 1818 Brixington Lane 0929 0959 hour 29 59 1729 1759 1829 Brixington Jubilee Drive 0933 1003 33 03 1733 1803 1833 Parkside Drive 0937 1007 37 07 1737 1807 1837 Churchill Road 0941 1011 41 11 1741 1811 1841 Brixington • Exmouth • Topsham • Exeter 57 26th December 2020 Brixington Lane 0929 0959 29 59 1729 1759 1829 Brixington Jubilee Drive 0933 1003 33 03 1733 1803 1833 Parkside Drive 0937 1007 then 37 07 1737 1807 1837 Churchill Road 0941 1011 at 41 11 1741 1811 1841 Exmouth Parade arr 0951 1021 these 51 21 until 1751 1821 1851 Exmouth Parade arr 0855 0925 0955 1025 times 55 25 1755 1825 Lympstone Saddlers Arms 0904 0934 1004 1034 each 04 34 1804 1834 Topsham The Nelson 0914 0944 1014 1044 hour 14 44 1814 1844 RDE Hospital Barrack Road 0925 0955 1023 1053 23 53 1823 1853 Exeter Sidwell St stop 19 0934 1004 1034 1104 34 04 1834 1904 Exeter • Newton Poppleford • Sidmouth 9 26th December 2020 Exeter Bus Station Bay 5 0831 then 31 1731 Middlemoor Police Station 0839 at 39 1739 Clyst St.