Whatever Happened to the Movie Theme Song?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coupe Mondiale 5-10 September 2017 Teatro “La Nuova Fenice” OSIMO

th 70Coupe Mondiale 5-10 September 2017 Teatro “La Nuova Fenice” OSIMO Confédération Internationale des Accordéonistes (CIA) www.coupemondiale2017.org CREATE CON LE NOSTRE MANI Pubblicita_02_A5_Verticale_Massimo_Pigini_29_08_2017.indd 1 29/08/2017 13:20:04 It is a great honor for me and for the city of Osimo to host the 70th edition of the Coupe Mondiale International Accordion Competitions. I strongly believe in the music as a tool for education and the development of interpersonal relationships. This event is a very important moment for our entire community. The accordion, born in the nearby Castelfidardo, represents our cultural roots, our history and our future. I want to welcome all the musicians who have come here from all over the world and I wish that they will realize their dreams and have a brilliant artistic career. Osimo is rich in history, an history of about 3,000 Simone years that left us a precious legacy: artifacts and Pugnaloni archaeological sites, artworks and buildings of Mayor of Osimo important and noble patrons. I want to thank the Artistic Director Mirco Patarini and all the people who worked hard to organize the event. Enjoy the music, enjoy the city and I wish for the guests an unforgettable stay here in Osimo. I remind everyone the important appointment with the 42th edition of PIF Castelfidardo, from 10 to 17 September 2017. The Mayor of Osimo Simone Pugnaloni - Osimo 2017 Coupe Mondiale th 70 3 Dear Delegates, Jury Members, Musicians, Competitors and Accordion Enthusiasts. I want to warmly welcome you all to Osimo for the 70th Coupe Mondiale hosted in 2017 by Italian Accordion Culture (IAC) under the auspicies of the Confédération Internationale des Accordéonistes (CIA) – IMC – UNESCO. -

5.3 Post-Cinematic Atavism

5.3 Post-Cinematic Atavism BY RICHARD GRUSIN In June 2002, for a plenary lecture in Montreal at the biennial Domitor conference on early cinema, I took the occasion of the much-hyped digital screening of Star Wars: Episode II–Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002) to argue that in entering the 21st century we found ourselves in the “late age of early cinema,” the more than century-long historical coupling of cinema with the sociotechnical apparatus of publicly projected celluloid film (“Remediation”). Two years later, in a lecture at a conference in Exeter on Multimedia Histories, I developed this argument in terms of what I called a “cinema of interactions,” arguing that cinema in the age of digital remediation could no longer be identified with its theatrical projection but must be understood in terms of its distribution across a network of other digitally-mediated formats like DVDs, websites, games, and so forth—an early call for something like what now goes under the name of “platform studies” (“DVDs”). In his recent book on “post-cinematic affect” Steven Shaviro has picked up on this argument in elaborating his own extremely powerful reading of the emergence of a post-cinematic aesthetic (70). I want to return the favor here to take up what I would characterize as a kind of “post-cinematic atavism” that has been emerging in the early 21st century as a counterpart to the aesthetic of post-cinematic affectivity that Shaviro so persuasively details. Sometimes considered under the name of “slow cinema” or “the new silent cinema” (or, as | 1 5.3 Post-Cinematic Atavism Selmin Kara puts it, “primordigital cinema”), post-cinematic atavism is not limited to art- house or independent films. -

Superman-The Movie: Extended Cut the Music Mystery

SUPERMAN-THE MOVIE: EXTENDED CUT THE MUSIC MYSTERY An exclusive analysis for CapedWonder™.com by Jim Bowers and Bill Williams NOTE FROM JIM BOWERS, EDITOR, CAPEDWONDER™.COM: Hi Fans! Before you begin reading this article, please know that I am thrilled with this new release from the Warner Archive Collection. It is absolutely wonderful to finally be able to enjoy so many fun TV cut scenes in widescreen! I HIGHLY recommend adding this essential home video release to your personal collection; do it soon so the Warner Bros. folks will know that there is still a great deal of interest in vintage films. The release is only on Blu-ray format (for now at least), and only available for purchase on-line Yes! We DO Believe A Man Can Fly! Thanks! Jim It goes without saying that one of John Williams’ most epic and influential film scores of all time is his score for the first “Superman” film. To this day it remains as iconic as the film itself. From the Ruby- Spears animated series to “Seinfeld” to “Smallville” and its reappearance in “Superman Returns”, its status in popular culture continues to resonate. Danny Elfman has also said that it will appear in the forthcoming “Justice League” film. When word was released in September 2017 that Warner Home Video announced plans to release a new two-disc Blu-ray of “Superman” as part of the Warner Archive Collection, fans around the world rejoiced with excitement at the news that the 188-minute extended version of the film - a slightly shorter version of which was first broadcast on ABC-TV on February 7 & 8, 1982 - would be part of the release. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2017 yS mposium Apr 12th, 3:00 PM - 3:30 PM Cue the Music: Music in Movies Kelsey M. DePree Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Composition Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Other Music Commons DePree, Kelsey M., "Cue the Music: Music in Movies" (2017). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 5. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2017/podium_presentations/5 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Music We Watch Kelsey De Pree Music History II April 5, 2017 Music is universal. It is present from the beginning of history appearing in all cultures, nations, economic classes, and styles. Music in America is heard on radios, in cars, on phones, and in stores. Television commercials feature jingles so viewers can remember the products; radio ads sing phone numbers so that listeners can recall them. In schools, students sing songs to learn subjects like math, history, and English, and also to learn about general knowledge like the days of the week, months of the year, and presidents of the United States. With the amount of music that is available, it is not surprising that music has also made its way into movie theatres and has become one of the primary agents for conveying emotion and plot during a cinematic production. -

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in Its Place

The Soundtrack: Putting Music in its Place. Professor Stephen Deutsch The Soundtrack Vol 1, No 1, 2008 tbc Intellect Press http://www.intellectbooks.co.uk/journals.php?issn=17514193 Abstract There are currently many books and journals on film music in print, most of which describe music as a separate activity from film, applied to images most often at the very end of the production process by composers normally resident outside the filmic world. This article endeavours to modify this practice by placing music within the larger notion of “the soundtrack”. This new model assumes that irrespective of industrial determinants, the soundtrack is perceived by an audience as such a unity; that music, dialogue, effects and atmospheres are heard as interdependent layers in the sonification of the film. We often can identify the individual sonic elements when they appear, but we are more aware of the blending they produce when sounding together, much as we are when we hear an orchestra. To begin, one can posit a definition of the word ‘soundtrack’. For the purposes of this discussion, a soundtrack is intentional sound which accompanies moving images in narrative film1. This intentionality does not exclude sounds which are captured accidentally (such as the ambient noise most often associated with documentary footage); rather it suggests that any such sounds, however recorded, are deliberately presented with images by film-makers.2 All elements of the soundtrack operate on the viewer in complex ways, both emotionally and cognitively. Recognition of this potential to alter a viewer’s reading of a film might encourage directors to become more mindful of a soundtrack’s content, especially of its musical elements, which, as we shall see below, are likely to affect the emotional environment through which the viewer experiences film. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

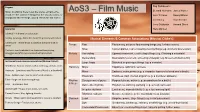

Knowledge Organiser

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

"Glory" John Legend and Common (2015) (From Selma Soundtrack)

"Glory" John Legend and Common (2015) (from Selma soundtrack) [John Legend:] [Common:] One day when the glory comes Selma is now for every man, woman and child It will be ours, it will be ours Even Jesus got his crown in front of a crowd One day when the war is won They marched with the torch, we gon' run with it We will be sure, we will be sure now Oh glory Never look back, we done gone hundreds of miles [Common:] From dark roads he rose, to become a hero Hands to the Heavens, no man, no weapon Facin' the league of justice, his power was the Formed against, yes glory is destined people Every day women and men become legends Enemy is lethal, a king became regal Sins that go against our skin become blessings Saw the face of Jim Crow under a bald eagle The movement is a rhythm to us The biggest weapon is to stay peaceful Freedom is like religion to us We sing, our music is the cuts that we bleed Justice is juxtapositionin' us through Justice for all just ain't specific enough Somewhere in the dream we had an epiphany One son died, his spirit is revisitin' us Now we right the wrongs in history True and livin' livin' in us, resistance is us No one can win the war individually That's why Rosa sat on the bus It takes the wisdom of the elders and young That's why we walk through Ferguson with our people's energy hands up Welcome to the story we call victory When it go down we woman and man up The comin' of the Lord, my eyes have seen the They say, "Stay down", and we stand up glory Shots, we on the ground, the camera panned up King pointed to -

Music Theory Through the Lens of Film

Journal of Film Music 5.1-2 (2012) 177-196 ISSN (print) 1087-7142 doi:10.1558/jfm.v5i1-2.177 ISSN (online) 1758-860X ARTICLE Music Theory through the Lens of Film FranK LEhman Tufts University [email protected] Abstract: The encounter of a musical repertoire with a theoretical system benefits the latter even as it serves the former. A robustly applied theoretic apparatus hones our appreciation of a given corpus, especially one such as film music, for which comparatively little analytical attention has been devoted. Just as true, if less frequently offered as a motivator for analysis, is the way in which the chosen music theoretical system stands to see its underlying assumptions clarified and its practical resources enhanced by such contact. The innate programmaticism and aesthetic immediacy of film music makes it especially suited to enrich a number of theoretical practices. A habit particularly ripe for this exposure is tonal hermeneutics: the process of interpreting music through its harmonic relationships. Interpreting cinema through harmony not only sharpens our understanding of various film music idioms, but considerably refines the critical machinery behind its analysis. The theoretical approach focused on here is transformation theory, a system devised for analysis of art music (particularly from the nineteenth century) but nevertheless eminently suited for film music. By attending to the perceptually salient changes rather than static objects of musical discourse, transformation theory avoids some of the bugbears of conventional tonal hermeneutics for film (such as the tyranny of the “15 second rule”) while remaining exceptionally well calibrated towards musical structure and detail. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

Cas Awards April 17, 2021

PRESENTS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS APRIL 17, 2021 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS PRE-SHOW MESSAGES PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Non-Theatrical Motion Pictures or Limited Series PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Documentary PRESIDENT’S REMARKS Karol Urban CAS MPSE Year in Review, In Memoriam INSTALLATION OF NEW BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – Half-Hour PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY Student Recognition Award PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Production PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Post-Production CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Non-Fiction, Variety, Music, Series or Specials PRESENTATION OF CAS FILMMAKER AWARD TO GEORGE CLOONEY PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Animated CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – One Hour PRESENTATION OF CAS CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD TO WILLIAM B. KAPLAN CAS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Live Action AFTER-AWARDS VIRTUAL NETWORKING RECEPTION THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 1 THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS DIAMOND SPONSORS PLATINUM SPONSORS STUDENT RECOGNITION AWARD SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS GROUP SILVER SPONSORS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 3 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Welcome to the 57th CAS Awards! It has been over a year since last we came together to celebrate our sound mixing community and we are so very happy to see you all.