Grouse Beater (Website)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2003

Nations and Regions: The Dynamics of Devolution Quarterly Monitoring Programme Scotland Quarterly Report November 2003 The monitoring programme is jointly funded by the ESRC and the Leverhulme Trust Introduction: James Mitchell 1. The Executive: Barry Winetrobe 2. The Parliament: Mark Shephard 3. The Media: Philip Schlesinger 4. Public Attitudes: John Curtice 5. UK intergovernmental relations: Alex Wright 6. Relations with Europe: Alex Wright 7. Relations with Local Government: Neil McGarvey 8. Finance: David Bell 9. Devolution disputes & litigation: Barry Winetrobe 10. Political Parties: James Mitchell 11. Public Policies: Barry Winetrobe ISBN: 1 903903 09 2 Introduction James Mitchell The policy agenda for the last quarter in Scotland was distinct from that south of the border while there was some overlap. Matters such as identity cards and foundation hospitals are figuring prominently north of the border though long-running issues concerned with health and law and order were important. In health, differences exist at policy level but also in terms of rhetoric – with the Health Minister refusing to refer to patients as ‘customers’. This suggests divergence without major disputes in devolutionary politics. An issue which has caused problems across Britain and was of significance this quarter was the provision of accommodation for asylum seekers as well as the education of the children of asylum seekers. Though asylum is a retained matter, the issue has devolutionary dimension as education is a devolved matter. The other significant event was the challenge to John Swinney’s leadership of the Scottish National Party. A relatively unknown party activist challenged Swinney resulting in a drawn-out campaign over the Summer which culminated in a massive victory for Swinney at the SNP’s annual conference. -

Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance After Snowden

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183-2439) 2015, Volume 3, Issue 3, Pages 12-25 Doi: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 Article “Veillant Panoptic Assemblage”: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance after Snowden Vian Bakir School of Creative Studies and Media, Bangor University, Bangor, LL57 2DG, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 9 April 2015 | In Revised Form: 16 July 2015 | Accepted: 4 August 2015 | Published: 20 October 2015 Abstract The Snowden leaks indicate the extent, nature, and means of contemporary mass digital surveillance of citizens by their intelligence agencies and the role of public oversight mechanisms in holding intelligence agencies to account. As such, they form a rich case study on the interactions of “veillance” (mutual watching) involving citizens, journalists, intelli- gence agencies and corporations. While Surveillance Studies, Intelligence Studies and Journalism Studies have little to say on surveillance of citizens’ data by intelligence agencies (and complicit surveillant corporations), they offer insights into the role of citizens and the press in holding power, and specifically the political-intelligence elite, to account. Atten- tion to such public oversight mechanisms facilitates critical interrogation of issues of surveillant power, resistance and intelligence accountability. It directs attention to the veillant panoptic assemblage (an arrangement of profoundly une- qual mutual watching, where citizens’ watching of self and others is, through corporate channels of data flow, fed back into state surveillance of citizens). Finally, it enables evaluation of post-Snowden steps taken towards achieving an equiveillant panoptic assemblage (where, alongside state and corporate surveillance of citizens, the intelligence-power elite, to ensure its accountability, faces robust scrutiny and action from wider civil society). -

Radio 4 Listings for 10 – 16 April 2021 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 10 – 16 April 2021 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 10 APRIL 2021 A Made in Manchester production for BBC Radio 4 his adored older brother Stephen was killed in a racially motivated attack. Determined to have an positive impact on SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m000twvj) young people, he became a teacher, and is now a motivational The latest news and weather forecast from BBC Radio 4. SAT 06:00 News and Papers (m000v236) speaker. The latest news headlines. Including the weather and a look at Tiggi Trethowan is a listener who contacted us with her story of the papers. losing her sight. SAT 00:32 Meditation (m000vjcv) Ade Adepitan is a paralympian and TV presenter whose latest A meditation following the death of His Royal Highness Prince series meets the people whose lives have already been affected Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, led by the Rev Dr Sam Wells, Vicar SAT 06:07 Open Country (m000twh9) by climate change. of St Martin-in-the-Fields, in London. Canna Alice Cooper chooses his Inheritance Tracks: Train Kept a Rollin’ by The Yardbirds and Thunderclap Newman, Something Canna is four miles long and one mile wide. It has no doctor in the air SAT 00:48 Shipping Forecast (m000twvl) and the primary school closed a few years ago. The islanders and your Thank you. The latest weather reports and forecasts for UK shipping. depend on a weekly ferry service for post, food and medical Producer: Corinna Jones supplies. Fiona Mackenzie and her husband, Donald, have lived on the island for six years. -

Edit Winter 2013/14

WINTER 2013|14 THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE + BILLET & GENERAL COUNCIL PAPERS LAUGHING MATTERS SKY HEAD OF COMEDY LUCY LUMSDEN ON THE FUNNY BUSINESS ROAD TO REFERENDUM HOW OUR EXPERTS ARE SHAPING THE DEBATE ALSO INSIDE AWARD-WINNING FILM'S STUNNING STORY | MEADOWS MEMORIES | ALUMNI WEEKEND PHOTOGRAPHS WINTER 2013|14 CONTENTS FOREWORD CONTENTS elcome to the Winter issue of Edit. The turn 12 26 W of 2014 heralds an exciting year for our staff, students and alumni, and indeed for Scotland. Our experts are part of history as they inform the debate on SAVE THE DATE the referendum (p10), while in a very different arena the 19 - 21 June 2014 University will play a major role in the Commonwealth Toronto, Canada Games in Glasgow (p5). In a nationwide public engagement project our researchers are exploring the 30 10 impact on Scotland of the First World War throughout the four years of its centenary (p17), and on p16 we look back at the heroism of an Edinburgh alumna during the conflict. If you are seeking light relief, you may have to thank Lucy Lumsden. She has commissioned some of 18 Britain's most successful television comedies of recent years, and in our interview (p8) she talks about the importance of making people laugh. We report on an exceptional string of successes, from Professor Peter Higgs's Nobel Prize (p5), to BAFTAs, including one for a documentary whose story is told by a remarkable 04 Update 18 What You Did Next Edinburgh graduate on pages 12-15. Find your friends in photos of our alumni weekend (p22) and, if you couldn't 08 The Interview 20 Edinburgh Experience Lucy Lumsden, make it, we hope to see you at the next one in 2015. -

RSE Welcomes 60 New Fellows

PRESS RELEASE Issued: 15/02/2017 RSE welcomes 60 new Fellows Outstanding Academics, Celebrated Professionals and Royalty Join Scotland’s National Academy The Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) is delighted to announce that HRH The Duke of Cambridge has been elected to become an RSE Royal Honorary Fellow. We much look forward to a long and fruitful relationship with HRH, as we have with our Patron, Her Majesty The Queen, and our other Royal Fellows.¹ Also announced today are the names of 59 distinguished individuals who have been elected to become Fellows of the RSE. Hailing from sectors that range from the arts, business, science and technology and academia, they join the current RSE Fellowship whose varied expertise supports the advancement of learning and useful knowledge in Scottish public life. The strength of the RSE lies in the breadth of disciplines represented by its Fellowship. This range of expertise enables the RSE to take part in a host of activities such as providing independent and expert advice to Government and Parliament, supporting aspiring entrepreneurs through mentorship, facilitating education programmes for young people and engaging the general public through educational events. The RSE is heartened to see a continued increase in the number of new Fellows from the arts, business and professional spheres. They include: MCDERMID, Val One of the biggest names in crime writing, Val McDermid is a founding writer of what has become known as the ‘tartan noir’ genre. GRICE, Sir Paul Chief Executive, Scottish Parliament. Sir Paul Grice played a major role in the establishment of the Scottish Parliament and fosters connections between the Scottish Parliament and the world of academia. -

C:\BAD Archive\12 2020\

Title Genre Date modified Comment Length Size MB C:\BAD Archive\12 2020\ 15 Minute Drama The Pursuits of Darleen Fyles Series 10 - » Drama 01.01.2021 Comic and touching drama series about a young married couple with learning disabilities. 00:13:47.742 15.83 15 Minute Drama The Pursuits of Darleen Fyles Series 10 - » Drama 01.01.2021 Award-winning drama of a young couple with learning disabilities and their life as parents 00:13:47.898 15.84 15 Minute Drama The Pursuits of Darleen Fyles Series 10 - » Drama 01.01.2021 Comic and touching drama series following young parents with learning disabilities. 00:13:37.580 15.64 15 Minute Drama The Pursuits of Darleen Fyles Series 10 - » Drama 01.01.2021 Delightful drama series about young parents with learning disabilities. 00:13:32.225 15.54 15 Minute Drama The Pursuits of Darleen Fyles Series 10 - » Drama 01.01.2021 Award-winning drama series about young parents with learning disabilities. 00:13:33.061 15.55 2000 Years of Radio Series 2 - 02. Beagle FM b007szjn » Comedy 01.01.2021 1836, and DJ Suzanne Canker joins Charlie Darwin aboard HMS Beagle. 00:13:56.440 15.97 2000 Years of Radio Series 2 - 03. Tempest FM b069npj8 » Comedy 01.01.2021 The shocking truth - who really wrote Shakespeare's plays? 00:14:09.632 16.23 2000 Years of Radio Series 2 - 04. Greensleeves FM » Comedy 01.01.2021 It's a right royal knockabout as Henry VIII wants a son. 00:14:07.046 16.18 2000 Years of Radio Series 2 - 05. -

Revealed:Scotland's Womenofinfluence

Source: Herald, The (Glasgow) {HW} Edition: Country: UK Date: Thursday 12, January 2012 Page: 6,7 Area: 1169 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 46257 Daily BRAD info: page rate £11,500.00, scc rate £26.50 Phone: 0141 302 7000 Keyword: Emeli Sande REVEALED: SCOTLAND’S TOP 50 WOMEN OF INFLUENCE From sport to music to politics and fashion, here is our list of the inspirational figures who will shape our nation in2012 nominations for her role in 2005’s The Girl In The Cafe. 50 JULIE FOWLIS, 32 Most likely to say: “Choose Glasgow. An award-winning Gaelic singer, multi-instrumentalist Choose HBO.” and radio broadcaster from North Uist, Fowlis spreads her culture as an international ambassador. She was 46 JO SWINSON, 31 dubbed the first Scottish Gaelic crossover star after Once the youngest MP in the Commons, Swinson becoming BBC Radio 2 Folk Singer of the Year. won in East Dunbartonshire in 2005 and 2010. She hit Watch out for: Her appearance at this month’s headlines last year when she led the campaign Celtic Connections in Glasgow. against misleading beauty adverts. She is currently parliamentary private secretary to Vince Cable and 49 LOUISE MARTIN, 65 deputy leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats. A competitive swimmer and a gymnastics team Least likely to say: “Because I’m worth it.” manager, Martin’s leadership was crucial to bringing the Commonwealth Games to Glasgow. Now vice- 45 KAREN CARGILL, 35 chair of the organising committee, she is also the The Scottish mezzo-soprano is now a global opera chair of the Sportscotland board. -

“Veillant Panoptic Assemblage”: Mutual Watching and Resistance To

Veillant Panoptic Assemblage: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass ANGOR UNIVERSITY Surveillance after Snowden Bakir, Vian Media and Communication DOI: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 08/10/2015 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Bakir, V. (2015). Veillant Panoptic Assemblage: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance after Snowden. Media and Communication, 3(3), 12-25. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 25. Sep. 2021 Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183-2439) 2015, Volume 3, Issue 3, Pages 12-25 Doi: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 Article “Veillant Panoptic Assemblage”: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance after Snowden Vian Bakir School of Creative Studies and Media, Bangor University, Bangor, LL57 2DG, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 9 April 2015 | In Revised Form: 16 July 2015 | Accepted: 4 August 2015 | Published: 20 October 2015 Abstract The Snowden leaks indicate the extent, nature, and means of contemporary mass digital surveillance of citizens by their intelligence agencies and the role of public oversight mechanisms in holding intelligence agencies to account. -

A List of the 238 Most Respected Journalists, As Nominated by Journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work Survey

A list of the 238 most respected journalists, as nominated by journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work survey Fran Abrams BBC Radio 4 & The Guardian Seth Abramson Freelance investigative journalist Kate Adie BBC Katya Adler BBC Europe Jonathan Ali BBC Christiane Amanpour CNN Lynn Ashwell Formerly Bolton News Mary-Ann Astle Stoke on Trent Live Michael Atherton The Times and Sky Sports Sue Austin Shropshire Star Caroline Barber CN Group Lionel Barber Financial Times Emma Barnett BBC Radio 5 Live Francis Beckett Author & journalist Vanessa Beeley Blogger Jessica Bennett New York Times Heidi Blake BuzzFeed David Blevins Sky News Ian Bolton Sky Sports News Susie Boniface Daily Mirror Samantha Booth Islington Tribune Jeremy Bowen BBC Tom Bradby ITV Peter Bradshaw The Guardian Suzanne Breen Belfast Telegraph Billy Briggs Freelance Tom Bristow Archant investigations unit Samuel Brittan Financial Times David Brown The Times Fiona Bruce BBC Michael Buchanan BBC Jason Burt Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph Carole Cadwalladr The Observer & The Guardian Andy Cairns Sky Sports News Michael Calvin Author Duncan Campbell Investigative journalist and author Severin Carrell The Guardian Reeta Chakrabarti BBC Aditya Chakrabortty The Guardian Jeremy Clarkson Broadcaster, The Times & Sunday Times Matthew Clemenson Ilford Recorder and Romford Recorder Michelle Clifford Sky News Patrick Cockburn The Independent Nick Cohen Columnist Teilo Colley Press Association David Conn The Guardian Richard Conway BBC Rob Cotterill The Sentinel, Staffordshire Alex Crawford -

Kirsty Wark Menopause & Me

Menopause ™ Summer 2017 matters HRT what can we believe? Kirsty Wark Menopause & Me A Vagina Dialogue - How Yoga can Help - A Positive Pulse - Keeping Calm - Woman to Woman - Menopause? Choose Spray Away Hot Flushes & Night Sweats with Promensil Cooling Spray Can be used on its own or alongside the Promensil Red Promensil Red Clover helps you stay comfortable Clover supplement range. during and after menopause. Promensil are offering readers of Menopause Matters an exclusive discount. SAVE 30% Off All Promensil Products Embrace the change Shop online at www.promensil.co.uk or call 01293 850210 quoting code MM30PR at the checkout. www.promensil.co.uk LINES OPEN 9am - 5pm Mon - Fri. Offer subject to availability. Open to UK residents aged 18 years and over living in the UK. Discount can only be used once, per person, per household and cannot be used in conjunction with any other offer. Offer ends September 30th 2017. • COMMENT • Menopause? WEBSITE: Menopausematters.co.uk PUBLISHER & MANAGING DIRECTOR: Dr Heather Currie Change, you can be Choose E-mail: [email protected] EDITOR: Pamela Brook E-mail: [email protected] a part of it ADVERTISING SALES MANAGER: Annie Preuss Spray Away Hot Flushes E-mail: [email protected] hange. Such a simple word, but one & Night Sweats with SOCIAL MEDIA MANAGER: that inspires many Therese Moncur C strong, mixed emotions... Promensil Cooling Spray E-mail: [email protected] fear, excitement, anxiety, WEBSITE MANAGER: optimism, trepidation... Rik Moncur E-mail: [email protected] That’s what I see in the many readers and patients I talk to about FORUM ADMINISTRATOR: what the change building up to and going Emma Goode through menopause brings, particularly when it comes to Email: [email protected] the subject of HRT. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for August 28Th, 2020

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for August 28th, 2020 For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: https://electricscotland.com/scotnews.htm Electric Scotland News Looks like the west coast of the USA and Canada are getting hit with some large bush fires. California and BC in particular. Hope any of our folks living there are safe. The GERS figures are out this week and so the annual event showing Scotland's finances will get the usual coverage. My preferred take is to check with Kevin Hague and I'll bring you his take next week. Lost my mobile phone this week. As I rarely use it and I keep it in my trouser packet it's was only when I changed my trousers I noticed it had gone. So now looking for a replacement and if you have any suggestions on what might be the best phone to get and the best plan do feel free to suggest one. I only use it for emergencies so it's usually switched of. All kinds of stories in the news this week so a bit longer list of stories than usual. Scottish News from this weeks newspapers Note that this is a selection and more can be read in our ScotNews feed on our index page where we list news from the past 1-2 weeks. I am partly doing this to build an archive of modern news from and about Scotland as world news stories that can affect Scotland and all the newsletters are archived and also indexed on Google and other search engines. -

Rts Programme

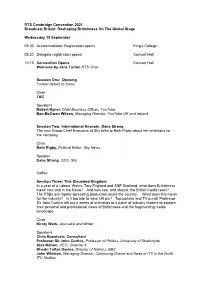

RTS Cambridge Convention 2021 Broadcast Britain: Reshaping Britishness On The Global Stage Wednesday 15 September 08:30 Accommodation Registration opens King’s College 08:30 Delegate registration opens Concert Hall 10:15 Convention Opens Concert Hall Welcome by Jane Turton RTS Chair Session One: Opening Further details to follow Chair TBC Speakers Robert Kyncl, Chief Business Officer, YouTube Ben McOwen Wilson, Managing Director, YouTube UK and Ireland Session Two: International Keynote: Dana Strong The new Group Chief Executive at Sky talks to Beth Rigby about her ambitions for the company. Chair Beth Rigby, Political Editor, Sky News Speaker Dana Strong, CEO, Sky Coffee Session Three: This Disunited Kingdom In a year of a Labour Wales, Tory England and SNP Scotland, what does Britishness mean now and in the future? And how can, and should, the British media react? The PSBs are rapidly spreading production round the country. What does this mean for the industry? Is it too late to save UK plc? Top pollster and TV pundit Professor Sir John Curtice will put a series of scenarios to a panel of industry leaders to explore their personal and professional views of Britishness and the fragmenting media landscape. Chair Kirsty Wark, Journalist and Writer Speakers Chris Banatvala, Consultant Professor Sir John Curtice, Professor of Politics, University of Strathclyde Alex Mahon, CEO, Channel 4 Rhodri Talfan Davies, Director of Nations, BBC John Whiston, Managing Director, Continuing Drama and Head of ITV in the North, ITV Studios Lunch Session Four: UK Keynote: Richard Sharp Chairman of the BBC since February, Richard Sharp gives his first speech to the RTS and talks to economist Stephanie Flanders about the global challenges and opportunities facing the corporation Chair Stephanie Flanders, Senior Executive Editor for Economics, Bloomberg News Speaker Richard Sharp, Chairman, BBC Session Five: UK Keynote: Carolyn McCall The ITV CEO speaks to journalist Dharshini David about the business and public service challenges ahead for the broadcaster.