Different Kinds of Composition / Compilation Within the Dudjom Revelatory Tradition 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery

Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Dominique Townsend All rights reserved ABSTRACT Materials of Buddhist Culture: Aesthetics and Cosmopolitanism at Mindroling Monastery Dominique Townsend This dissertation investigates the relationships between Buddhism and culture as exemplified at Mindroling Monastery. Focusing on the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, I argue that Mindroling was a seminal religio-cultural institution that played a key role in cultivating the ruling elite class during a critical moment of Tibet’s history. This analysis demonstrates that the connections between Buddhism and high culture have been salient throughout the history of Buddhism, rendering the project relevant to a broad range of fields within Asian Studies and the Study of Religion. As the first extensive Western-language study of Mindroling, this project employs an interdisciplinary methodology combining historical, sociological, cultural and religious studies, and makes use of diverse Tibetan sources. Mindroling was founded in 1676 with ties to Tibet’s nobility and the Fifth Dalai Lama’s newly centralized government. It was a center for elite education until the twentieth century, and in this regard it was comparable to a Western university where young members of the nobility spent two to four years training in the arts and sciences and being shaped for positions of authority. This comparison serves to highlight commonalities between distant and familiar educational models and undercuts the tendency to diminish Tibetan culture to an exoticized imagining of Buddhism as a purely ascetic, world renouncing tradition. -

'The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa' by Sarah Harding

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Himalaya No. 1 & 2 Article 20 2005 Book review of 'The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa' by Sarah Harding Anne Z. Parker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Parker, Anne Z.. 2005. Book review of 'The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa' by Sarah Harding. HIMALAYA 25(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol25/iss1/20 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIFE AND REVELATIONS OF PEMA LINGPA SARAH HARDING REVIEWED BY ANNE z. PARKER, P H D. Sarah Harding's The Life and Revelations of Pema human form of dialogues. The characters bring the Lingpa is a significant contribution to Himalayan life and times of Padmasambhava into vivid focus history and Buddhist literature. It adds substantially in the conversations and the details of their lives to the limited English language literature available as members of the royal court. The teachings come on Bhutan. It brings to life two key historical alive through the personalities of these characters figures, one from Bhutan and one from Tibet: Pema as they encounter the great teacher and request Lingpa, a teacher, mystic, and treasure revealer; teachings from him. -

The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Translated by Sarah Harding, Forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; Reviewed by D

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 26 Number 1 People and Environment: Conservation and Management of Natural Article 22 Resources across the Himalaya No. 1 & 2 2006 The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley D. Phillip Stanley Naropa University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Stanley, D. Phillip. 2006. The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa translated by Sarah Harding, forward by Gangteng Rinpoche; reviewed by D. Phillip Stanley. HIMALAYA 26(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol26/iss1/22 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. of its large alluvial plains, extensive irrigation institutional integrity that they have managed to networks, and relatively egalitarian land-ownership negotiate with successive governments in Kangra patterns, like other Himalayan communities it is also to stay self-organized and independent, and to undergOing tremendous socio-economic changes get support from the state for the rehabilitation of due to the growing influence of the wider market damaged kuhls. economy. Kuhl regimes are experiencing declining Among the half dozen studies of farmer-managed interest in farming, decreasing participation, irrigation systems of the Himalaya, this book stands increased conflict, and the declining legitimacy out for its skillful integration of theory, historically of customary rules and authority structures. -

Pema Lingpa.Pdf

Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page i The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page ii Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iii The Life and Revelations of Pema Lingpa ሓ Translated by Sarah Harding Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york ✦ boulder, colorado Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page iv Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 www.snowlionpub.com Copyright © 2003 Sarah Harding All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. isbn 1-55939-194-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page v Contents Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche vii Translator’s Preface ix Introduction by Holly Gayley 1 1. Flowers of Faith: A Short Clarification of the Story of the Incarnations of Pema Lingpa by the Eighth Sungtrul Rinpoche 29 2. Refined Gold: The Dialogue of Princess Pemasal and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 51 3. The Dialogue of Princess Trompa Gyen and the Guru, from Lama Jewel Ocean 87 4. The Dialogue of Master Namkhai Nyingpo and Princess Dorje Tso, from Lama Jewel Ocean 99 5. The Heart of the Matter: The Guru’s Red Instructions to Mutik Tsenpo, from Lama Jewel Ocean 115 6. A Strand of Jewels: The History and Summary of Lama Jewel Ocean 121 Appendix A: Incarnations of the Pema Lingpa Tradition 137 Appendix B: Contents of Pema Lingpa’s Collection of Treasures 142 Notes 145 Bibliography 175 Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vi Pema Lingpa_ALL 0709 7/7/09 12:18 PM Page vii Foreword by Gangteng Tulku Rinpoche his book is an important introduction to Buddhism and to the Tteachings of Guru Padmasambhava. -

Magic, Healing and Ethics in Tibetan Buddhism

Magic, Healing and Ethics in Tibetan Buddhism Sam van Schaik (The British Library) Aris Lecture in Tibetan and Himalayan Studies Wolfson College, Oxford, 16 November 2018 I first met Michael Aris in 1997, while I was in the midst of my doctoral work on Jigme LingPa and had recently moved to Oxford. Michael resPonded graciously to my awkward requests for advice and helP, meeting with me in his college rooms, and rePlying to numerous emails, which I still have printed out and on file (this was the 90s, when we used to print out emails). Michael also made a concerted effort to have the Bodleian order an obscure Dzogchen text at my request, giving me a glimPse into his work as an advocate of Tibetan Studies at Oxford. And though I knew Anthony Aris less well, I met him several times here in Oxford and elsewhere, and he was always a warm and generous Presence. When I came to Oxford I was already familiar with Michael’s work, esPecially his book on Jigme LingPa’s account of India in the eighteenth century, and his study of the treasure revealer Pema LingPa. Michael’s aPProach, symPathetic yet critical, ProPerly cautious but not afraid to exPlore new connections and interPretations, was also an insPiration to me. I hoPe to reflect a little bit of that sPirit in this evening’s talk. What is magic? So, this evening I’m going to talk about magic. But what is ‘magic’ anyway? Most of us have an idea of what the word means, but it is notoriously difficult to define. -

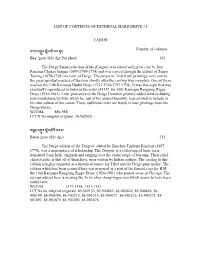

List of Contents of External Hard Drive #1

LIST OF CONTENTS OF EXTERNAL HARD DRIVE #1 CANON 0!8-8>o:-&{-+#{-.:-/v+- Number of volumes Bka' 'gyur (Sde dge Par phud) 103 The Derge Parpu redaction of the Kangyur was edited with great care by Situ Panchen Chokyi Jungne (1699/1700-1774) and was carved through the efforts of Tenpa Tsering (1678-1738) the ruler of Derge. The parpu or "first fruit" printings were sent to the great spiritual masters of the time shortly after the carving was complete. One of them reached the 13th Karmapa Dudul Dorje (1733/1734-1797/1798). It was this copy that was eventually reproduced in India at the order of H.H. the 16th Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje (1924-1981). Later protectors of the Derge Gonchen printery added texts including new translations by Situ, which he, out of his natural humility, had omitted to include in his own edition of the canon. These additional texts are found in later printings from the Derge blocks. W22084 886-988 LCCN for inkprint original: 76-902420. 0%,-8>o:-&{-+#{8m-.:-1- Bstan 'gyur (Sde dge) 213 The Derge edition of the Tengyur, edited by Zhuchen Tsultrim Rinchen (1697- 1774), was a masterpiece of scholarship. The Tengyur is a collection of basic texts translated from Indic originals and ranging over the entire range of learning. Their chief characteristic is that all of them have been written by Indian authors. The catalog to this edition is highly regarded as a historical source for Tibet and the Derge principality. The edition which has been scanned here was prepared as a part of the funeral rites for H.H. -

Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~

~ Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~ Jigme Lingpa: A Guide to His Works It is hard to overstate the importance of Jigme Lingpa to the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. This itinerant yogi, along with Rongzom Mahapandita, Longchenpa, and-later-Mipham Rinpoche, are like four pillars of the tradition. He is considered the incarnation of both the great master Vimalamitra and the Dharma king Trisong Detsen. After becoming a monk, he had a vision of Mañjuśrīmitra which caused him to change his monks robes for the white shawl and long hair of a yogi. In his late twenties, he began a long retreat during which he experienced visions and discovered termas. A subsequent retreat a few years later was the container for multiple visions of Longchenpa, the result of which was the Longchen Nyingthig tradition of terma texts, sadhanas, prayers, and instructions. What many consider the best source for understanding Jigme Lingpa's relevance, and his milieu is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's Masters of Meditation and Miracles: Lives of the Great Buddhist Masters of India and Tibet. While the biographical coverage of him only comprises about 18 pages, this work provides the clearest scope of the overall world of Jigme Lingpa, his line of incarnations, and the tradition and branches of teachings that stem from him. Here is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's account of his revelation of the Longchen Nyingtik. "At twenty-eight, he discovered the extraordinary revelation of the Longchen Nyingthig cycle, the teachings of the Dharmakāya and Guru Rinpoche, as mind ter. In the evening of the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month of the Fire Ox year of the thirteenth Rabjung cycle (1757), he went to bed with an unbearable devotion to Guru Rinpoche in his heart; a stream of tears of sadness continuously wet his face because he was not 1 in Guru Rinpoche's presence, and unceasing words of prayers kept singing in his breath. -

A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 49 A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF FOUR TIBETAN LAMAS AND THEIR ACTIVITIES IN SIKKIM TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Summarised English translation by Saul Mullard and Tsewang Paljor Translators’ note It is hoped that this summarised translation of Lama Tsultsem’s biography will shed some light on the lives and activities of some of the Tibetan lamas who resided or continue to reside in Sikkim. This summary is not a direct translation of the original but rather an interpretation aimed at providing the student, who cannot read Tibetan, with an insight into the lives of a few inspirational lamas who dedicated themselves to various activities of the Dharma both in Sikkim and around the world. For the benefit of the reader, we have been compelled to present this work in a clear and straightforward manner; thus we have excluded many literary techniques and expressions which are commonly found in Tibetan but do not translate easily into the English language. We apologize for this and hope the reader will understand that this is not an ‘academic’ translation, but rather a ‘representation’ of the Tibetan original which is to be published at a later date. It should be noted that some of the footnotes in this piece have been added by the translators in order to clarify certain issues and aspects of the text and are not always a rendition of the footnotes in the original text 1. As this English summary will be mainly read by those who are unfamiliar with the Tibetan language, we have refrained from using transliteration systems (Wylie) for the spelling of personal names, except in translated footnotes that refer to recent works in Tibetan and in the bibliography. -

Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal

Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Angowski, Elizabeth. 2019. Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029522 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal A dissertation presented by Elizabeth J. Angowski to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 24, 2019 © 2019 Elizabeth J. Angowski All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Janet Gyatso Elizabeth J. Angowski Literature and the Moral Life: Reading the Early Biography of the Tibetan Queen Yeshe Tsogyal ABSTRACT In two parts, this dissertation offers a study and readings of the Life Story of Yeshé Tsogyal, a fourteenth-century hagiography of an eighth-century woman regarded as the matron saint of Tibet. Focusing on Yeshé Tsogyal's figurations in historiographical and hagiographical literature, I situate my study of this work, likely the earliest full-length version of her life story, amid ongoing questions in the study of religion about how scholars might best view and analyze works of literature like biographies, especially when historicizing the religious figure at the center of an account proves difficult at best. -

TBRC Tranche 3 Collection

TBRC Tranche 3 Collection 1 CANON, CANONICAL WORKS, AND MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS W27919 LCCN 83-907127 number of volumes: 1 a mdo rwa rgya'i bka' 'gyur gyi dkar chag (bde bar gsegs pa'i gsung rab gans can gyi skad du 'gyur ro cog gi phyi mo par du bskrun pa'i dkar chag mdo rgyud chos kyi sgo brgya cig car 'byed pa'i lde mig) main author: bstan pa'i nyi ma (paN chen 04 bstan pa'i nyi ma) b. 1782 d. 1853 publication information: dharamsala: library of tibetan works & archives, 1983 subject classification: bka' 'gyur (rwa rgya); dkar chag Notice of contents and historical background of the Ragya Monastery blocks of the Tibetan Kangyur; no set of this 19th century redaction survives. W23702 LCCN none number of volumes: 226 bstan 'gyur (gser gyi lag bris ma) subject classification: canonical publication information: 18th century manuscript 18th century manuscript Tanjur. The Tanjur comprises Tibetan translations of commentaries and supporting texts to the Kanjur. These were originally written in Sanskrit and translated into Tibetan W23190 LCCN 77-902297 number of volumes: 1 sgom rim thog mtha' bar gsum (the five bhavanakrama of kamalasila and vimalamitra : a collection of texts on the nature and practice of buddhist contemplative realisation) main author: kamalasila b. 7th cent. publication information: gangtok: gonpo tseten, 1977 subject classification: sgom rim thog mtha' bar gsum (khrid) Five treatises on meditation and the Madhyamika approach by Kamalasila and Vimalamitra W23203 LCCN 83-907117 number of volumes: 1 dkyil chog rdo rje phreng ba dang rdzogs pa'i rnal 'byor gyi 'phreng ba (the vajravali and nispannayogavali in tibetan : a reproduction of the mandala texts of abhayakaragupta in their tibetan tranalation from ancient manuscripts from hemis monastery in ladakh ; with manikasrijnana's topical outline to the vajravali) main author: a bha yA kA ra gupta b. -

HH Dudjom Rinpoche II

This Bronze Statue of Dudjom Lingpa is Worshipped at the Dudjom Buddhist Association The Life Story of His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche (1904-1987) by Vajra Master Yeshe Thaye Prediction on His Holiness Dudjom into a noble family in the southeastern Tibetan province of Pemakod, one of the four “hidden lands” of Guru Rinpoche. Rinpoche He was of royal Tsenpo lineage, It was predicted by Urgyen Dechen Lingpa that “in the descended from Nyatri Tsenpo and future in Tibet, on the east of the Nine-Peaked Mountain, in from Puwo Kanam Dhepa, the king the sacred Buddhafield of the self-originated Vajravarahi, of Powo. His father Kathok Tulku there will be an emanation of Drogben, of royal lineage, Norbu Tenzing, was a famous tulku named Jnana. His beneficial activities are in accord with of the Pemakod region from Kathok the Vajrayana although he conducts himself differently, Monastery. His mother, who had unexpectedly, as a little boy with astonishing intelligence. descended from Ratna Lingpa and He will either discover new Terma or preserve the old belonged to the local member of Terma. Whoever has connections with him will be taken the Pemakod tribe, was called to Ngayab Ling (Zangdok Palri).” Namgyal Drolma. His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche has always His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche’s Birth been specially connected with the His Holiness Dudjom Rinpoche was born in the Water Kathok Monastery, as can be seen th H.H. Dudjom Rinpoche at Dragon year of the 15 Rabjung Cycle (on June 10, 1904), from his previous incarnations: his His Youth (1) 48 ninth manifestation was Dampa Dayshek (A.D. -

Khenpo's Diamond — Living with Wisdom

One Diamond, One Day KHENPO’S DIAMOND LIVING WITH WISDOM offered by Khenpo Sodargye | volume 1 | 2018 CONTENTS Preface 2 January 3 February 15 March 28 April 43 May 57 June 71 July 83 August 95 September 109 October 122 November 139 December 154 Postscript 168 Preface From Jan 1, this year (2018), I started to post Buddhist teachings every day on my Tibetan Weibo page. These teachings carry great blessings as they are from different Buddhist texts and have been highly valued by great masters of the past. Their wisdom is so great that they are often quoted by my teachers from memory. I have also memorized them. Now I translate them into Chinese (and then into English) and share them with you one at a time, every day. If you can memorize the words and practice them according to their meaning, you will gain great benefit. Sodargye February 9, 2018 January 001 January 1, 2018 Do not lose your own path; Do not disturb others’ minds. — His Holiness Jigme Phuntsok Rinpoche 002 January 3, 2018 (1) Conducting oneself with virtuous deeds and the accumulation of merit, Drives away suffering and brings happiness, Bestows blessings, Actualizes all wishes, Destroys hosts of maras, And helps one to swiftly attain bodhi. — The Play in Full 003 January 3, 2018 (2) My property, my honor — all can freely go, My body and my livelihood as well. And even other virtues may decline, But never will I let my mind regress. — Shantideva 4 004 January 4, 2018 Each day one should take to heart a few words Of the scriptural advice that one needs; Before very long one will become wise, Just as ant hills are built or honey is made.