Korematsu: Reflections on My Father’S Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri

March 2021 2’s/2.5 Roly Poly and 2.5/3’s Ladybug Classes LEAD TEACHER: Ms. Colleen SUPPORT TEACHERS: Ms. Iriana, Adam, Rachel, Mel and Star CHILDS INTERESTS AND/OR: Language & Literacy: STU Physical Development & Health: Perceptual-Motor & Movement & Hygiene Math: color green, shape rectangle, #8 Science: Molecules to Organisms & Ecosystems Self-Regulation: Shared Use of space & Materials Social & Emotional: Getting Along with Others Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Enrichment 1 2 3 4 5 Activities Activities at at3/3:30pm: 3pm: HistoryLanguage & Social & LanguageMath & Phy. Dev.Math & Health Phy. Dev.Science & Health Self-ScienceRegulation Nat’l Dentist Day Monday-Soccer Tuesday-Music LiteracyScience Literacy Show & Tell Show & Tell Wednesday-Gymnastics Cooking Project Thursday-Ballet NatWorld’l Spaghetti Compliment Day ReadNat Across’l Bird America Day WorldEpiphany Wildlife Day OrthodoxNat’l Grammar Christmas Day WearParents your Night Little Out Tree Happy Mew Year for Day Day T-shirt6-9pm Day Cats Day 8 9 10 11 12 Nat’l Cereal Day SocialSelf- &Regulation Emotional SocialLanguage & Emotional & VisualMath Arts & Phy.Community Dev. & HelperHealth Dance,Science Music, Nat’l K9 Veterans Literacy Architecture Theatre Day Wear a hat! National Chocolate NatNat’l ’Proofreadingl Milk Day KissCooking a Ginger Project Day StephenNat’l Pack Foster your Day OrthodoxShow &New Tell Year NatNat’l Girl’l Hat Scout Day Day Law Enforcement Covered Cherry Day Day Nat’l Meatball Day Lunch Day Appreciation Day 15 16 17 18 19 Daylight Saving CLOSEDScience HistorySelf-Regulation & Social SocialLanguage & Emotional & LanguageMath & Phy. Dev.Math & Health Start of Spring FOR MARTIN Science Literacy Literacy LUTHER KING JR. -

City's Website at NOTICE

AGENDA OF A REGULAR MEETING - NATIONAL CITY CITY COUNCIL/ COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION – HOUSING AUTHORITY OF THE CITY OF NATIONAL CITY ONLINE ONLY MEETING https://www.nationalcityca.gov/webcast LIVE WEBCAST COUNCIL CHAMBERS CIVIC CENTER 1243 NATIONAL CITY BOULEVARD NATIONAL CITY, CALIFORNIA TUESDAY, JANUARY 19, 2021 – 6:00 PM NOTICE: The health and well-being of National City residents, visitors, ALEJANDRA SOTELO-SOLIS Mayor and employees during the COVID-19 outbreak remains our top priority. The City of National City is coordinating with the County of San Diego JOSE RODRIGUEZ Health Human Services Agency, and other agencies to take measures Vice Mayor to monitor and reduce the spread of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). The World Health Organization has declared the outbreak a global MARCUS BUSH pandemic and local and state emergencies have been declared Councilmember providing reprieve from certain public meeting laws such as the Brown Act. RON MORRISON Councilmember As a result, the City Council Meeting will occur only online to ensure MONA RIOS the safety of City residents, employees and the communities we serve. Councilmember A live webcast of the meeting may be viewed on the city’s website at www.nationalcityca.gov. For Public Comments see “PUBLIC COMMENTS” section below ORDER OF BUSINESS: Public sessions of all Regular Meetings of the City Council / Community Development Commission - Housing Authority (hereafter referred to as Elected Body) begin at 6:00 p.m. on the first and third Tuesday of each month. Public Hearings begin at 6:00 p.m. unless otherwise noted. Closed Meetings begin in Open Session at 5:00 p.m. -

March 28, 2014 President Barack

March 28, 2014 President Barack Obama The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. President: We write on behalf of the United States Commission on Civil Rights (hereafter “the Commission”) to request formal recognition and establishment by Congress of January 30th of every year henceforth as a permanent national holiday--National Fred Koremastu Day-- and that the President issue an Executive Order declaring January 30th the Fred Korematsu National Day of Service in recognition of Fred T. Korematsu’s contribution to upholding civil rights and liberties for all citizens in our country. Fred Korematsu is a civil rights champion who was thrust into our public consciousness in 1942, when at the age of 23 he refused to go to the United States’ internment camps established for Japanese Americans in the wake of the 1941 Pearl Harbor attacks.1 Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, authorized the Secretary of War and all supporting federal agencies to detain and relocate Americans of Japanese ancestry to internment camps in the interest of national security.2 Mr. Korematsu was arrested and convicted of going against the government’s orders.3 He subsequently appealed, and his case went all the way to the Supreme Court which ruled against Mr. Korematsu.4 For the Commission, this is not merely a part of history, but is personal. Commissioner Michael Yaki’s father and his family were held in an internment camp during World War II. Mr. Korematsu’s case was overturned in 1983 after a pro-bono team of attorneys re- opened his case on the basis of government misconduct after discovering the government had hidden documents which consistently showed the federal government knew that Japanese Americans were not engaged in any acts of sabotage or any other act which could be construed as against the interests of the United States. -

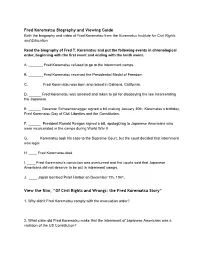

Fred Korematsu Biography and Viewing Guide View the Film, “Of

Fred Korematsu Biography and Viewing Guide Both the biography and video of Fred Korematsu from the Korematsu Institute for Civil Rights and Education Read the biography of Fred T. Korematsu and put the following events in chronological order, beginning with the first event and ending with the tenth event. A. _______ Fred Korematsu refused to go to the internment camps. B. _______ Fred Korematsu received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. C. ______ Fred Korematsu was born and raised in Oakland, California. D. ______ Fred Korematsu was arrested and taken to jail for disobeying the law incarcerating the Japanese. E. ______ Governor Schwartzenegger signed a bill making January 30th, Korematsu’s birthday, Fred Korematsu Day of Civil Liberties and the Constitution. F. ______ President Ronald Reagan signed a bill, apologizing to Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in the camps during World War II. G. _____ Korematsu took his case to the Supreme Court, but the court decided that internment was legal. H. ____ Fred Korematsu died. I. ____ Fred Korematsu’s conviction was overturned and the courts said that Japanese Americans did not deserve to be put in internment camps. J. ____ Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941. View the film, “Of Civil Rights and Wrongs: the Fred Korematsu Story” 1. Why didn’t Fred Korematsu comply with the evacuation order? 2. What claim did Fred Korematsu make that the internment of Japanese Americans was a violation of the US Constitution? 3, What claim did majority on the Supreme Court make that the mass incarceration of Japanese of Americans was legal and justified? 4. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Page 1 of 261

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Page 1 of 261 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Points No. Title Author Level 46456 Come Here, Tiger! Moran, Alex 0.3 0.5 EN 66246 Show and Tell Mayer, Mercer 0.3 0.5 EN 9340 EN Snow Joe Greene, Carol 0.3 0.5 41850 Clifford Makes a Friend Bridwell, Norman 0.4 0.5 EN 58042 I Can Read, Too: Book #9 Sargent, Dave/Pat 0.4 0.5 EN 66204 My Trip to the Zoo Mayer, Mercer 0.4 0.5 EN 9334 EN Please, Wind? Greene, Carol 0.4 0.5 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 66200 Country Fair Mayer, Mercer 0.5 0.5 EN 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 49483 Down on the Farm Lascaro, Rita 0.5 0.5 EN 9314 EN Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol 0.5 0.5 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 31542 Mine's the Best Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 EN 35665 What Day Is It? Trimble, Patti 0.5 0.5 EN 66242 Beach Day Mayer, Mercer 0.6 0.5 EN 72887 Cat Who Barked, The Sargent, Dave 0.6 0.5 EN 42150 EN Don't Cut My Hair! Wilhelm, Hans 0.6 0.5 9018 EN Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. 0.6 0.5 9364 EN Funny Baby, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 72885 Little Big Cat Sargent, Dave 0.6 0.5 EN 9383 EN Magic Beans, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 3051 EN My Dog's the Best! Calmenson, Stephanie 0.6 0.5 9391 EN Three Bears, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9392 EN Three Goats, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9393 EN Three Little Pigs, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 https://c.na6.content.force.com/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=00P8000000BHUWr 2/ 22/ 2012 Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice -

2019 Ag Request Legislation Fred Korematsu & Gordon Hirabayashi

2019 AG REQUEST LEGISLATION FRED KOREMATSU & GORDON HIRABAYASHI DAY WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE? Key Support: During WWII, Japanese-Americans and Japanese immigrants were TBD incarcerated under federal exclusion and incarceration orders. Fred Prime Sponsors: Korematsu and Gordon Hirabayashi refused to comply with orders Sen. Hasegawa: D they believed were unconstitutional. Both were arrested—Hirabayashi Rep. Santos: D in Washington, Korematsu in California. Their legal challenges were unsuccessful, and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the incarceration Office Contacts: orders. In the 1980s, Korematsu’s and Hirabayashi’s convictions were Yasmin Trudeau overturned by federal courts. Korematsu and Hirabayashi should be Legislative Affairs Director celebrated for their courage to stand up to injustice. [email protected] Brittany Gregory WHY IS THIS CHANGE NECESSARY? Deputy Legislative Director A day of recognition would honor their legacies and the thousands of [email protected] incarcerated Issei, Nisei, and Sansei, civil rights defenders, and WWII 1: Andy Hobbs, “75 years ago, Japanese internment sparked veterans from Washington. It would honor Hirabayashi, a born-and- economic and cultural fears in raised Washingtonian and alumnus of the University of Washington. Puget Sound,” The News Tribune, This day of recognition will augment the state’s existing “Civil Liberties February 19, 2017. Day of Remembrance,” which is observed every February 19 and also commemorates the struggles against incarceration. K E Y As many as 14,000 Washingtonians of Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese ancestry were imprisoned during the S T 60 Second World War; 60% were American citizens. A PERCENT T AROUND THE U.S.: Since 2010, a number of other states including California, Hawai’i, Virginia, Utah, Georgia, Illinois, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Michigan and Florida, as well as numerous municipalities, have commemorated January 30 as “Fred Korematsu Day” in celebration of civil liberties and the Constitution, but no state has yet named a day for Gordon Hirabayashi. -

A Conversation on Japanese American Incarceration & Its Relevance to Today

CONVERSATION KIT Courtesy of the National Archives Tuesday, May 17, 2016 1:00-2:00 pm EDT, 10:00-11:00 am PDT Smithsonian National Museum of American History Kenneth E. Behring Center IN WORLD WAR II NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT . 3 Introduction . 3 Program Details . 4 Regional Summit Locations . 4 When, Where, and How to Participate . 4 Join the Conversation . 5 Central Questions . 6 Panelists and Participants . 7 Common Core State Standards . 9 National Standards for History . 10 SECTION II: LANGUAGE . 11 Statement on Terminology . 12 SECTION III: LESSON PLANS . 14 Lesson Plans and Resources on Japanese American Incarceration . 15 Lesson Ideas for Japanese American Incarceration and Modern Parallels . 17 SECTION IV: YOUTH LEADERSHIP AND TAKING ACTION . 18 What Can You Do? . 19 SECTION V: ADDITIONAL RESOURCES . .. 21 NATIONAL YOUTH SUMMIT JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION 3 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION TO THE NATIONAL SUMMIT Thank you for participating in the Smithsonian’s National Youth Summit on Japanese American Incarceration. This Conversation Kit is designed to provide you with lesson activities and ideas for leading group discussions on the issues surrounding Japanese American incarceration and their relevance today. This kit also provides details on ways to participate in the Summit. The National Youth Summit is a program developed by the National Museum of American History in collaboration with Smithsonian Affiliations. This program is funded by the Smithsonian’s Youth Access Grants. Pamphlet, Division of Armed Forces History, Office of Curatorial Affairs, National Museum of American History Smithsonian Smithsonian National Museum of American History National Museum of American History Kenneth E. -

Japanese Internment Case Not “Good Law”

11/13/2020 Japanese Internment Case Not "Good Law" - Legal Aggregate - Stanford Law School Japanese Internment Case Not “Good Law” November 18, 2016 By David Alan Sklansky (https://law.stanford.edu/directory/david-alan-sklansky/) It is appalling to see the shameful confinement of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps during World War II bandied about (http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/18/us/politics/japanese-internment-muslim-registry.html) as some kind of “precedent” for how the United States might respond to the threat of terrorism. And it is distressing to hear Korematsu v. United States (https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/323/214), the notorious decision upholding the internment policy, described at “good law,” or “technically still on the books.” That suggestion is sometimes made even by people who see the Korematsu decision, correctly, as a disgrace. Legitimating Korematsu is not as bad as legitimating the internment, but it is a mistake, and a dangerous one. Korematsu is not “good law”—“technically” or otherwise—and it is important to understand why. Professor David Sklansky Fred Korematsu, born and raised in Oakland, California, was the son of Japanese immigrants. In May 1942 the Army ordered (http://www.javadc.org/java/docs/1942-05- 03%3B%20WDC%20%20Civilian%20Exclusion%20Order%20No.34,pg4_dg%3Bay.pdf) “All Persons of Japanese Ancestry” in the San Francisco Bay Area to report to an “Assembly Center,” for “evacuation.” Korematsu was convicted later that year of failing to show up. The ACLU took Korematsu’s case to the Supreme Court, which upheld the conviction in a split decision (https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/323/214/). -

Laws - by State

Laws - By State Bill Name Title Action Summary Subject AL S 32 Civics Tests for Students 04/25/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Alabama to take the Education Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AL SJR 82 Bridge Designation 04/25/2017 - This resolution names a bridge after Johannes Whetstein and his family, who Resolutions Enacted immigrated to the U.S. in 1734, in order to recognize their contributions to the development of Autauga County in Alabama. AR H 1041 Application of Foreign 04/07/2017 - This law prohibits Arkansas institutions from applying foreign laws that violate Law Enforcement Law in Courts Enacted the Arkansas Constitution or the U.S. Constitution. AR H 1281 Human Services Division 04/05/2017 - This human services appropriations law includes funds for refugee resettlement. Budgets of County Operations Enacted AR H 1539 Naturalization Test 03/14/2017 - This law requires students enrolled in a public institution in Arkansas to take the Education Passage Requirement Enacted civics portion of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalization exam and score a 60 out of 100 prior to receiving a high school diploma. AR S 531 School for Mathematics 03/28/2017 - This law exempts U.S. residents who attend The Arkansas School for Education and Arts Provisions Enacted Mathematics, Sciences, and the Arts from paying tuition, fees, and housing, while requiring international students to pay for tuition, fees, and housing. -

WSC JACL Newsletter

March 2019 WATSONVILLE-SANTA CRUZ JACL “The Bridge 䱋” The Voice of Our Community Afer the rain has stopped, a branch of droplets waits for the light to change Inside this issue ameagari Haiku 1 eda no shizuku mo Donations 1 hikari matsu Watsonville-Santa Cruz JACL - Haiku by Bob Gomez - Upcoming JACL Calendar 2 in dedication to Mas Hashimoto Translation by Emi Sato - Day of Remembrance 2019 2 - JACL NCWNP District Gala Fundraiser 3 (Bob and Denise Gomez, Program Directors of Kokoro no Gakko) - National & W-SC JACL Scholarships 4 DONATIONS - 2019 California Mother of the Year Award 6 We would like to thank those who have Friends & Family of Nisei Veterans 6 generously donated since our last issue. It is Kawakami Sister City News 8 through your constant support that we continue to be a vibrant part of our community. Kokoro no Gakko 8 • Jason Higashi for DOREF-newsletter ”in honor of Mas Hashimoto for his years of dedication in Medical Thought 8 storytelling in print and in person regarding Onward! 9 DOR and his experiences." • Robert and Mary Oka for DOREF-newsletter Senior Corner 11 • Sam and Yae Sakamoto for DOREF-greatest Watsonville Bonsai Club 15 need • Sachi and Phil Snyder for DOREF-greatest need Norman Mineta and His Legacy 15 "in remembrance of Tadashi Tar Mino, Ayako Barbara Mino, and Iwao Mino.” Watsonville Taiko & Shinsei Daiko 15 • Grant Ujifusa of NY for the DOREF newsletter Watsonville Buddhist Temple 16 • Yoko Umeda for DOREF-greatest need • Alan and Gayle Uyematsu for DOREF-greatest Westview Presbyterian Chimes 17 need • Watsonville Bonsai Club donation for use of Look for our website: the JACL Hall !1 WatsonvilleSantaCruzJACL.org March 2019 WATSONVILLE - SANTA CRUZ JACL UPDATE Upcoming JACL Calendar of Events and Deadlines Watsonville-Santa Cruz Chapter Board Meetings: Monthly chapter board meetings are held on the fourth Thursday (except in November and December) at the Watsonville-Santa Cruz JACL Kizuka Hall, 150 Blackburn Street, Watsonville, CA 95076 starting at 6:30 pm. -

Asian Law Caucus Marks 25 Anniversary of Historic Civil Rights Decision with Launch of Fred Korematsu Institute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Johanna Silva Waki or Tuesday, April 7, 2009 Stephanie Ong Stillman, Hope Road Consulting Phone: (415) 882-4673 Asian Law Caucus Marks 25 th Anniversary of Historic Civil Rights Decision with Launch of Fred Korematsu Institute SAN FRANCISCO – In honor of a man who became a civil rights icon for defying the mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, the Asian Law Caucus will officially launch the Fred T. Korematsu Institute for Civil Rights and Education (http://fredkorematsu.org) at the organization’s annual event on Thursday, April 30, in San Francisco. “The Institute will play a role in a new era of collaborative efforts to further secure the rights of all people of color,” said Karen Korematsu-Haigh, Korematsu’s daughter. “We want to develop and support a new generation of ambassadors of justice that embody my father’s courage and conviction.” “In the long history of our country's constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls … Plessy, Brown, Parks. To that distinguished list, today we add the name of Fred Korematsu,” said President Bill Clinton in January 1998 in awarding Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom. During World War II, Korematsu was a 22-year-old welder in Oakland, Calif., who defied military orders that ultimately led to the internment of 110,000 Japanese Americans, including Korematsu and his family who were removed from their homes, held first in the Tanforan Race Track Assembly Center in San Bruno, Calif., and then incarcerated in the Topaz internment camp in Utah. -

How Trump V. Hawaii Reincarnated Korematsu and How They Can Be Overruled

Disarming Jackson’s (Re)Loaded Weapon: How Trump v. Hawaii Reincarnated Korematsu and How They Can Be Overruled Kaelyne Yumul Wietelman* Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................44 I. History and Context for KOREMATSU V. UNITED STATES ......................46 A. Pearl Harbor and Executive Order 9066 ...........................................46 B. Korematsu’s Case and the Supreme Court ........................................48 C. Post–World War II Remedies ..............................................................49 II. The Travel Ban and its Parallels to KOREMATSU ...............................51 A. The History of the Ban ........................................................................51 B. The Parallels Between Korematsu and Trump v. Hawaii .................53 III. How The Court got KOREMATSU and TRUMP V. HAWAII Wrong ...........57 A. The Dissenting Opinions ....................................................................57 B. The Nonapplication of Strict Scrutiny in Korematsu .......................59 IV. Subsequent Cases that Eroded KOREMATSU and TRUMP V. HAWAII ...61 A. Hamdi v. Rumsfeld’s Destruction of Korematsu ..............................61 B. Hedges v. Obama .................................................................................64 C. Ziglar v. Abbasi and the Need for Legislation ..................................64 V. Recommendations for Legislation and Congressional Action ......66 A. Amending the Non-Detention