Bannockburn Heritage Landscape Study Key Nodes • Kawarau Station Homestead and Farm Building Cluster • Homestead and Farm Building Clusters from C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Liquidation)

Liquidators’ First Report on the State of Affairs of Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 8 March 2019 Contents Introduction 2 Statement of Affairs 4 Creditors 5 Proposals for Conducting the Liquidation 6 Creditors' Meeting 7 Estimated Date of Completion of Liquidation 8 Appendix A – Statement of Affairs 9 Appendix B – Schedule of known creditors 10 Appendix C – Creditor Claim Form 38 Appendix D - DIRRI 40 Liquidators First Report Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) 1 Introduction David Ian Ruscoe and Malcolm Russell Moore, of Grant Thornton New Zealand Limited (Grant Thornton), were appointed joint and several Interim Liquidators of the Taratahi Agricultural Training Centre (Wairarapa) Trust Board (in Liquidation) (the “Trust” or “Taratahi”) by the High Count in Wellington on 19 December 2018. Mr Ruscoe and Mr Moore were then appointed Liquidators of the Trust on 5th February 2019 at 10.50am by Order of the High Court. The Liquidators and Grant Thornton are independent of the Trust. The Liquidators’ Declaration of Independence, Relevant Relationships and Indemnities (“DIRRI”) is attached to this report as Appendix D. The Liquidators set out below our first report on the state of the affairs of the Companies as required by section 255(2)(c)(ii)(A) of the Companies Act 1993 (the “Act”). Restrictions This report has been prepared by us in accordance with and for the purpose of section 255 of the Act. It is prepared for the sole purpose of reporting on the state of affairs with respect to the Trust in liquidation and the conduct of the liquidation. -

5 Day Otago Rail Trail Daily Trip Notes

5 Day Otago Rail Trail Daily trip notes A 5 Day – 4 Night cycle from Clyde to Middlemarch along the original Otago Central Rail Trail. Steeped in history and with a constant easy gradient, it is a great way to view scenery not seen from the highway. Trip highlights Cycle the historic Rail Trail. Spectacular views of Mt Cook and the Southern Alps. Explore the old gold mining town of Clyde. Cycle through tunnels and over rail bridges. Try your hand at ‘curling’ ‑ bowls on ice! Take a journey on the famous Taieri Gorge Train. This tour is a combined tour with Natural High and Adventure South. DAY 1 – Christchurch to Clyde DAY 2 – Clyde to Lauder DAY 3 – Lauder to Ranfurly DAY 4 – Ranfurly to Dunedin DAY 5 – Dunedin to Christchurch The trip Voted #2 ‘Must Do Adventure’ in the most recent edition of Lonely Planet’s New Zealand guide book, this adventure will have you cycling back in time to New Zealand’s rural past along a trail that has been specially converted for walkers, mountain bikers and horse riders - with no motor vehicles allowed! The Trail follows the old Central Otago branch railway line from Clyde to Middlemarch, passing through many towns along the way. This trip is not just about the cycling but rather exploring the many small towns and abandoned gold diggings as well as meeting the locals. Along the way you can even try your hand Natural High Tel 0800 444 144 - email: [email protected] - www.naturalhigh.co.nz at the ancient art of curling (bowls on ice). -

New Accessibility Map for Southland District Council Area

SOUTHERN REGION JULY 2016 New Accessibility Map for Southland District Council Area Travelling around Southland will now be easier Council Offices and community organisations for disabled people; this is because the including CCS Disability Action branch offices Southland District Council has just published in Invercargill and Dunedin. People who want an accessibility map of Southland. As well as a copy can e-mail Janet Thomas for a copy showing accessible restaurants, toilets etc. the ([email protected]) or find the map shows accessible museums, libraries and map on the Southland District Council website walking tracks. The map also shows contact http://www.southlanddc.govt.nz/home/ details of restaurants etc. so that people can accessibility-map/ contact them for further information. The council has worked closely with disabled people to find out what they wanted in the map. As well as this Janet Thomas from the council visited fifty toilets in the area to make sure that they were accessible. Janet also advised people responsible for the toilets if repairs were necessary. Mel Smith, the Acting CCS Disability Action Southern Regional Manager said that the development of the map was a wonderful example of a council working with the disabled community to develop the map which will be of use to all. The map was developed as part of the Council’s inclusive communities strategy with funding from Think Differently. Copies of the map are available from Southland District In this Issue: Swipe Cards for Total Mobility Taxi Users in Otago ... 7 New Accessibility Map for Southland DC ................. -

Natural Hazards on the Taieri Plains, Otago

Natural Hazards on the Taieri Plains, Otago Otago Regional Council Private Bag 1954, 70 Stafford St, Dunedin 9054 Phone 03 474 0827 Fax 03 479 0015 Freephone 0800 474 082 www.orc.govt.nz © Copyright for this publication is held by the Otago Regional Council. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part provided the source is fully and clearly acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-478-37658-6 Published March 2013 Prepared by: Kirsty O’Sullivan, natural hazards analyst Michael Goldsmith, manager natural hazards Gavin Palmer, director environmental engineering and natural hazards Cover images Both cover photos are from the June 1980 floods. The first image is the Taieri River at Outram Bridge, and the second is the Taieri Plain, with the Dunedin Airport in the foreground. Executive summary The Taieri Plains is a low-lying alluvium-filled basin, approximately 210km2 in size. Bound to the north and south by an extensive fault system, it is characterised by gentle sloping topography, which grades from an elevation of about 40m in the east, to below mean sea level in the west. At its lowest point (excluding drains and ditches), it lies about 1.5m below mean sea level, and has three significant watercourses crossing it: the Taieri River, Silver Stream and the Waipori River. Lakes Waipori and Waihola mark the plain’s western boundary and have a regulating effect on drainage for the western part of the plains. The Taieri Plains has a complex natural-hazard setting, influenced by the combination of the natural processes that have helped shape the basin in which the plain rests, and the land uses that have developed since the mid-19th century. -

Alexandra | Cromwell Tracks Brochure

OTAGO Welcome to Central Otago Nau mai, haere mai Alexandra and Cromwell townships are good bases from which to Alexandra explore Central Otago, a popular outdoor destination for mountain Further information biking, walking, four-wheel driving, fishing and sharing picnics. Cromwell tracks The vast ‘big sky’ landscape offers a variety of adventures and places Tititea/Mt Aspiring National Park Visitor Centre to explore. 1 Ballantyne Road Central Otago Wanaka 9305 Key PHONE: (03) 443 7660 Mountain bike tracks Walking tracks EMAIL: [email protected] Grade 1: Easiest Walking track www.doc.govt.nz EASIEST Grade 2: Easy Short walk Grade 3: Intermediate Tramping track Grade 4: Advanced Route ADVANCED No dogs No horses 4WD Ski touring Historic site Picnic Horse riding Fishing Swimming Dog walking Hunting Lookout Motorcycling Mountain biking Published by: R174401 Tititea/Mount Aspiring National Park Visitor Centre New Zealand Cycle Trail Ardmore Street, Wanaka PO Box 93, Wanaka 9343 Managed by Department of Conservation Phone: 03 443 7660 Email: [email protected] Managed by Central Otago District Council September 2020 Editing and design: Managed by Cromwell & Districts Te Rōpū Ratonga Auaha, Te Papa Atawhai Promotions Group Creative Services, Department of Conservation This publication is produced using paper sourced from Landmarks well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. Toyota Kiwi Guardians Front page image photo credit: Bannockburn Sluicings. Photo: C. Babirat Mountain Bikers of Alexandra (MOA) Some quick recreation ideas History Choosing a picnic spot Māori Great picnic spots can be found at Lanes Dam, Alexandra (Aronui Although there were never large numbers of Māori living in this area, Dam), Mitchells Cottage and Bendigo/Logantown. -

Download Our Interplanetary Cycle Brochure

Otago Museum Shop. Museum Otago and a 10% discount at the the at discount 10% a and Perpetual Guardian Planetarium Guardian Perpetual Otago Museum Shop. Museum Otago $2 off Adult admission to the the to admission Adult off $2 Otago Museum Shop. Museum Otago and a 10% discount at the the at discount 10% a and Present this flyer to receive to flyer this Present and a 10% discount at the the at discount 10% a and Perpetual Guardian Planetarium Guardian Perpetual Perpetual Guardian Planetarium Guardian Perpetual $2 off Adult admission to the the to admission Adult off $2 exploring our amazing universe. amazing our exploring $2 off Adult admission to the the to admission Adult off $2 Present this flyer to receive to flyer this Present Guardian Planetarium to continue continue to Planetarium Guardian Present this flyer to receive to flyer this Present and Otago Museum’s Perpetual Perpetual Museum’s Otago and exploring our amazing universe. amazing our exploring cycle journey, visit the observatory the visit journey, cycle exploring our amazing universe. amazing our exploring Guardian Planetarium to continue continue to Planetarium Guardian When you have completed your your completed have you When Guardian Planetarium to continue continue to Planetarium Guardian and Otago Museum’s Perpetual Perpetual Museum’s Otago and and Otago Museum’s Perpetual Perpetual Museum’s Otago and of our Solar System Solar our of cycle journey, visit the observatory observatory the visit journey, cycle cycle journey, visit the observatory observatory the visit journey, cycle When you have completed your your completed have you When University of Otago, School of Surveying. -

Download an Otago Brochure

Otago Main Centres The DUNEDIN Tohu Whenua Story Nau mai, haere mai ki te kaupapa o Tohu Whenua. Tohu Whenua are places that have shaped Aotearoa DunedinNZ New Zealand. Located in stunning landscapes and rich with stories, they offer some of our best heritage experiences. QUEENSTOWN Walk in the footsteps of extraordinary and ordinary New Zealanders and hear about the deeds, struggles, triumphs and innovations that make us who we are. With Tohu Whenua as your guide, embark on a journey to some of our most important landmarks and immerse Destination Queenstown yourself in our diverse and unique history. Visit Tohu Whenua in Northland, Otago and West Coast. ŌAMARU Local Information In the event of an emergency, dial 111 To report or check current road conditions Weather in Otago can change unexpectedly. on the state highway call 0800 4 HIGHWAYS Make sure you take appropriate warm clothing, (0800 44 44 49) or check online at a waterproof jacket, food and water when www.journeys.nzta.govt.nz/otago/ embarking on walks in the area. Claudia Babirat Cover image credits. Top: Oamaru, Waitaki NZ. Bottom left: Arrowtown, Claudia Babirat. Bottom right: Otago Central Rail Trail, James Jubb. Larnach Castle TWBR02 www.tohuwhenua.nz/otago The Otago 1 Tss Earnslaw 5 Otago Central Rail Trail 9 DUNEDIN RAILWAY STATION Lady of the Lake Pedalling Otago’s rural heart A first-class destination Story The TSS Earnslaw is one of the world’s oldest and New Zealand’s original Great Ride, this popular Ornate and flamboyant, Dunedin’s railway station largest remaining steamships and has graced Lake cycle journey offers a taste of genuine Southern is today considered one of the world’s best. -

Otago Rail Trail Ladies E-Bike Tour a Journey Into the Past Through Spectacular Central Otago!

Otago Rail Trail Ladies E-Bike Tour A Journey Into The Past Through Spectacular Central Otago! tour highlights • Historical gold works • Vast wide open expanses • Rich in history • Easy trail riding • Great company • Experienced attentive guide official partner Tuatara Tours is proud to be in an official partnership with The New Zealand Cycle Trail. The objective of the partnership is to create a nationwide network of cycle trails that connect the Great Rides with the rest of New Zealand. the tour The Otago Central Rail Trail is ideal for cyclists who wish to see some spectacular Central Otago scenery, at an easy pace, on flat gravelled terrain. Trains typically travel through hills, around hills but (if it can be avoided) not uphill (the maximum gradient is 2%). tours run The Rail Trail runs for 150kms between Clyde and Middlemarch (close to Dunedin), passing through the towns of Clyde, Alexandra, Chatto Creek, Tours run: November - April Omakau, Lauder, Oturehua, Wedderburn, Ranfurly, Waipiata and Hyde. tour cost • The tours are designed to be 5 days of fun cycling with no 2019/ 2020 pressure and no competition, ride at your own pace. • You get detailed practical hands on lessons on how to ride and NZD$2200 Starting in Christchurch: operate your E-Bike. Includes the cost of an E Bike for the duration of the tour • You will be amazed at how easy E-Bikes are to ride and operate options & supplements and how easy the whole idea of biking a trail has become. Single Supplement: NZD$475 about your guide fast facts Join Helen our experienced bike tour guide on this tour. -

Waste Disposal Facilities

Waste Disposal Facilities S Russell Landfill ' 0 Ahipara Landfill ° Far North District Council 5 3 Far North District Council Claris Landfill - Auckland City Council Redvale Landfill Waste Management New Zealand Limited Whitford Landfill - Waste Disposal Services Tirohia Landfill - HG Leach & Co. Limited Hampton Downs Landfill - EnviroWaste Services Ltd Waiapu Landfill Gisborne District Council Tokoroa Landfill Burma Road Landfill South Waikato District Council Whakatane District Council Waitomo District Landfill Rotorua District Sanitary Landfill Waitomo District Council Rotorua District Council Broadlands Road Landfill Taupo District Council Colson Road Landfill New Plymouth District Council Ruapehu District Landfill Ruapehu District Council New Zealand Wairoa - Wairoa District Council Waiouru Landfill - New Zealand Defence Force Chatham Omarunui Landfill Hastings District Council Islands Bonny Glenn Midwest Disposal Limited Central Hawke's Bay District Landfill S ' Central Hawke's Bay District Council 0 ° 0 4 Levin Landfill Pongaroa Landfill Seafloor data provided by NIWA Horowhenua District Council Tararua District Council Eves Valley Landfill Tasman District Council Spicer Valley Eketahuna Landfill Porirua City Council Silverstream Landfill Tararua District Council Karamea Refuse Tip Hutt City Council Buller District Council Wainuiomata Landfill - Hutt City Council Southern Landfill - Wellington City Council York Valley Landfill Marlborough Regional Landfill (Bluegums) Nelson City Council Marlborough District Council Maruia / Springs -

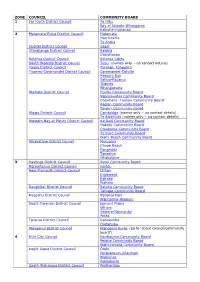

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board -

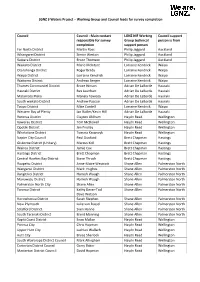

LGNZ 3 Waters Working Group and Council Leads for Survey Completion

LGNZ 3 Waters Project – Working Group and Council leads for survey completion Council Council - Main contact LGNZ NIF Working Council support responsible for survey Group technical person is from completion support person Far North District Martin Ross Philip Jaggard Auckland Whangarei District Simon Weston Philip Jaggard Auckland Kaipara District Bruce Thomson Philip Jaggard Auckland Waikato District Marie McIntyre Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Otorohanga District Roger Brady Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waipa District Lorraine Kendrick Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Waitomo District Andreas Senger Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Thames Coromandel District Bruce Hinson Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Hauraki District Rex Leonhart Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Matamata Piako Manaia Tewiata Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki South waikato District Andrew Pascoe Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Taupo District Mike Cordell Lorraine Kendrick Waipa Western Bay of Plenty Ian Butler/Kevin Hill Adrian De LaBorde Hauraki Rotorua District Clayton Oldham Haydn Read Wellington Kawerau District Tom McDowell Haydn Read Wellington Opotiki District Jim Findlay Haydn Read Wellington Whakatane District Tomasz Krawczyk Haydn Read Wellington Napier City Council Paul Dunford Brett Chapman Hastings Gisborne District (Unitary) Marcus Koll Brett Chapman Hastings Wairoa District Jamie Cox Brett Chapman Hastings Hastings District Brett Chapman Brett Chapman Hastings Central Hawkes Bay District Steve Thrush Brett Chapman Hastings Ruapehu District Anne-Maire Westcott Shane Allen Palmerston North Wanganui District -

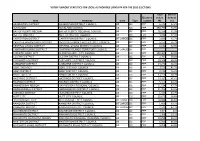

Voter Turnout Statistics for Local Authorities Using Fpp for the 2013 Elections

VOTER TURNOUT STATISTICS FOR LOCAL AUTHORITIES USING FPP FOR THE 2013 ELECTIONS Total Overall Electoral voters turnout Area Authority ward Type system (N) (%) ASHBURTON DISTRICT ASHBURTON DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,810 53.3% AUCKLAND AUCKLAND COUNCIL All CC FPP 292,790 34.9% BAY OF PLENTY REGION BAY OF PLENTY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 78,938 41.0% BULLER DISTRICT BULLER DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,694 62.4% CARTERTON DISTRICT CARTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP 2,880 45.7% CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT CENTRAL HAWKE'S BAY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,151 55.2% CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT CENTRAL OTAGO DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 6,722 52.9% CHATHAM ISLANDS DISTRICT CHATHAM ISLANDS TERRITORY COUNCIL AT LARGE DC FPP CHRISTCHURCH CITY CHRISTCHURCH CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 103,467 42.9% CLUTHA DISTRICT CLUTHA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 2,707 59.8% FAR NORTH DISTRICT FAR NORTH DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 18,308 48.9% GISBORNE DISTRICT GISBORNE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 14,272 48.3% GORE DISTRICT GORE DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3720 41.7% GREY DISTRICT GREY DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 3,193 45.3% HAMILTON CITY HAMILTON CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP 37,276 38.3% HASTINGS DISTRICT HASTINGS DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 19,927 47.8% HAURAKI DISTRICT HAURAKI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 5,375 40.4% HAWKE'S BAY REGION HAWKE'S BAY REGIONAL COUNCIL All RC FPP 51,524 47.7% HOROWHENUA DISTRICT HOROWHENUA DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 11,700 52.9% HURUNUI DISTRICT HURUNUI DISTRICT COUNCIL All DC FPP 1,327 44.7% HUTT CITY HUTT CITY COUNCIL All CC FPP