The Ti Tree Creek Camp Study Will Sanders 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health

The International Indigenous Policy Journal Volume 3 Article 6 Issue 3 Water and Indigenous Peoples September 2012 Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia Heather Browett Flinders University, [email protected] Meryl Pearce Flinders University, [email protected] Eileen M. Willis Flinders University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Browett, H. , Pearce, M. , Willis, E. M. (2012). Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia. Th e International Indigenous Policy Journal, 3(3) . DOI: 10.18584/iipj.2012.3.3.6 Cost Implications of Hard Water on Health Hardware in Remote Indigenous Communities in the Central Desert Region of Australia Abstract The provision of services such as power, water, and housing for Indigenous people is seen as essential in the Australian Government’s "Closing the Gap" policy. While the cost of providing these services, in particular adequate water supplies, is significantly higher in remote areas, they are key contributors to improving the health of Indigenous peoples. In many remote areas, poor quality groundwater is the only supply available. Hard water results in the deterioration of health hardware, which refers to the facilities considered essential for maintaining health. This study examined the costs associated with water hardness in eight communities in the Northern Territory. Results show a correlation between water hardness and the cost of maintaining health hardware, and illustrates one aspect of additional resourcing required to maintain Indigenous health in remote locations. Keywords Indigneous, water, health hardware, hard water Acknowledgments Thanks are extended to Power and Water, Northern Territory for funding this project. -

Outstations Through Art: Acrylic Painting, Self‑Determination and the History of the Homelands Movement in the Pintupi‑Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1

8 Outstations through art: Acrylic painting, self-determination and the history of the homelands movement in the Pintupi-Ngaanyatjarra Lands Peter Thorley1 Australia in the 1970s saw sweeping changes in Indigenous policy. In its first year of what was to become a famously short term in office, the Whitlam Government began to undertake a range of initiatives to implement its new policy agenda, which became known as ‘self-determination’. The broad aim of the policy was to allow Indigenous Australians to exercise greater choice over their lives. One of the new measures was the decentralisation of government-run settlements in favour of smaller, less aggregated Indigenous-run communities or outstations. Under the previous policy of ‘assimilation’, living arrangements in government settlements in the Northern Territory were strictly managed 1 I would like to acknowledge the people of the communities of Kintore, Kiwirrkura and Warakurna for their assistance and guidance. I am especially grateful to Monica Nangala Robinson and Irene Nangala, with whom I have worked closely over a number of years and who provided insights and helped facilitate consultations. I have particularly enjoyed the camaraderie of my fellow researchers Fred Myers and Pip Deveson since we began working on an edited version of Ian Dunlop’s 1974 Yayayi footage for the National Museum of Australia’s Papunya Painting exhibition in 2007. Staff of Papunya Tula Artists, Warakurna Artists, Warlungurru School and the Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tutaku (Purple House) have been welcoming and have given generously of their time and resources. This chapter has benefited from discussion with Bob Edwards, Vivien Johnson and Kate Khan. -

Yuendumu Remote Towns Jobs Profle

Remote Towns Jobs Profile YUENDUMU JOBS PROFILE YUENDUMU 1 © Northern Territory of Australia 2018 Preferred Reference: Department of Trade, Business and Innovation, 2017 Remote Towns Jobs Profiles, Northern Territory Government, June 2018, Darwin. Disclaimer The data in this publication were predominantly collected by conducting a face-to-face survey of businesses within town boundaries during mid-2017. The collection methodology was created in accordance with Australian Bureau of Statistics data quality framework principles. Data in this publication are only reflective of those businesses reported on as operating in the town at the time of data collection (see table at the end of publication for list of businesses reported on). To comply with privacy legislation or where appropriate, some data in this publication may have been adjusted and will not reflect the actual data reported by businesses. As a result of this, combined with certain data not being reported by some businesses, some components may not add to totals. Changes over time may also reflect business' change in propensity to report on certain data items rather than actual changes over time. Total figures have generally not been adjusted. Caution is advised when interpreting the comparisons made to the earlier 2011 and 2014 publications as the businesses identified and reported on and the corresponding jobs may differ between publications. Notes for each table and chart are alphabetically ordered and listed at the end of the publication. Any use of this report for commercial purposes is not endorsed by the Department of Trade, Business and Innovation. JOBS PROFILE YUENDUMU 2 Contents Yuendumu ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Crime Problem'' of the Northern Territory Intervention

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Analysis and Policy Observatory (APO) Addressing the “crime problem’’ of the Northern Territory Intervention: alternate paths to regulating minor driving offences in remote Indigenous communities Dr Thalia Anthony Dr Harry Blagg Report to the Criminology Research Advisory Council Grant: CRG 38/09-10 June 2012 1 This is a project supported by a grant from the Criminology Research Grants. The views expressed are the responsibility of the author and are not necessarily those of the Council. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 5 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Quantitative findings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Qualitative findings ............................................................................................................................. 7 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 8 RATIONALE AND AIMS OF STUDY ........................................................................................................ -

Yuendumu Dialysis Support Service Feasibility Study Final Report

Yuendumu Dialysis Support Service Feasibility Study Final Report May 2008 Western Desert Nganampa Walytja Palyantjaku Tjutaku Aboriginal Corporation Table of Contents 1. The Yuendumu Dialysis Services Feasibility Study 4 2. Executive Summary 5 2.1 Key Findings 5 3. Background 7 3.1 The WDNWPT Story 7 3.2 WDNWPT Services for Yanangu families 8 3.3 WDNWPT Structure 9 3.4 WDNWPT Dialysis Service Model 10 3.5 Membership of Current WDNWPT Governing Committee 11 4. Renal Patient Data for Yuendumu and Surrounding Communities 12 4.1 Current Renal Patient Numbers for Yuendumu, Nyirripi, Willowra and Yuelamu 12 4.2 Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Figures for Yuendumu, Nyirripi, Willowra and Yuelamu 12 4.3 Interpreting CKD Data 12 5. Consultations 15 5.1 Feasibility Study Consultation, Milestone and Meeting Timeline 15 5.2 Process for Consulting Renal Patients, Family and Community 17 Members 5.3 Development of a Yuendumu Dialysis Service Model 17 5.3.1 Community Based Dialysis 17 5.3.2 Social and Community Support 18 5.4 Key Meetings 19 5.4.1 Patient and Family Meeting, Purple House, 26 November, 2007 19 5.4.2 Family and Community Meeting, Yuendumu, 4th February, 2008 21 5.4.3 Yapa Kidney Committee Meeting, 4th February, 2008 22 6. Resolution to Kurra Aboriginal Corporation 25 7. Glossary 30 2 ATTACHMENTS A. Patient List 31 B. Kidney Committee Members 32 C. Consultations (detail) 33 D. Meeting Attendance Lists 41 E. Initial Consultation Questionnaire 43 F. Support for Warlpiri Dialysis Patients during the Feasibility Study 44 G. Job Descriptions 45 1. -

A Study of the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Australian

A Study of the Art Gallery of New South Wales and Australian Aboriginal Art: Aboriginal Perspectives and Representations in State Art Galleries Vanessa Russ Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), College of Fine Arts, UNSW This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia School of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts May 2013 i Vanessa Russ: Dissertation Abstract This study of the Art Gallery of New South Wales explores the role that Australian Aboriginal art has had in one important state institution. It also provides the groundwork for furthering our understanding of how state art galleries manage their discourses of Australian and Aboriginal identities. The search by Aboriginal people, for belonging and trust in national representations, continues to challenge state art galleries. If as art historian Amelia Jones suggests the notion of art, art history and art institutions are inventions, then such inventions should make room for new art and new art theory (Jones 23). While state art galleries are currently working to generate new displays of Australian art that include Australian Aboriginal art, there remains no complete study of how any state art gallery has managed its Aboriginal collections. This study of the role of Australian Aboriginal art within the Art Gallery of New South Wales provides evidence of personal advocacy as the driving force behind its achievements. Here personal advocacy and by extension, cultural subjectivity, is the key to the creation of an art gallery. ii Vanessa Russ: Dissertation Table of Content 1. Abstract page ii 2. Table of Content page iii 3. -

Rainfall-Linked Megafires As Innate Fire Regime Elements in Arid

fevo-09-666241 July 5, 2021 Time: 15:55 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 05 July 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.666241 Rainfall-Linked Megafires as Innate Fire Regime Elements in Arid Australian Spinifex (Triodia spp.) Grasslands Boyd R. Wright1,2,3*, Boris Laffineur4, Dominic Royé5, Graeme Armstrong6 and Roderick J. Fensham4,7 1 Department of Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Science, The University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia, 2 School of Agriculture and Food Science, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia, 3 The Northern Territory Herbarium, Department of Land Resource Management, Alice Springs, NT, Australia, 4 Queensland Herbarium, Toowong, QLD, Australia, 5 Department of Geography, University of Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain, 6 NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Broken Hill, NSW, Australia, 7 School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, St. Lucia, QLD, Australia Edited by: Large, high-severity wildfires, or “megafires,” occur periodically in arid Australian spinifex Eddie John Van Etten, (Triodia spp.) grasslands after high rainfall periods that trigger fuel accumulation. Edith Cowan University, Australia Proponents of the patch-burn mosaic (PBM) hypothesis suggest that these fires Reviewed by: Ian Radford, are unprecedented in the modern era and were formerly constrained by Aboriginal Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), patch burning that kept landscape fuel levels low. This assumption deserves scrutiny, Australia as evidence from fire-prone systems globally indicates that weather factors are the Christopher Richard Dickman, The University of Sydney, Australia primary determinant behind megafire incidence, and that fuel management does not *Correspondence: mitigate such fires during periods of climatic extreme. We reviewed explorer’s diaries, Boyd R. -

Volatile Substance Misues in Alice Springs Town Camps.Pdf

Background Results and Discussion 4. Mt Theo - A community driven outstation program located near •Volatile substances (VS) are: •What is the impact of the new legislation? Yuendumu (350 km north west of Alice Springs) - Volatile solvents - Courts can mandate treatment for individuals ‘at risk’ of severe - Developed by community members in the early 1990’s, and - Aerosols harm into appropriate programs petrol sniffing and other inhalant use has been effectively - Gases eradicated in Yuendumu as a result - Nitrates Two main elements to the Mt Theo program: Aromatic paints a) Mt Theo Outstation (a reactive treatment program) 140 •The regulation of legal substances such as VS is a contentious issue: Volatile Substances in an kilometers from Yuendumu - The misuse of VS is not a criminal act Alice Springs supermarket - Caters for ‘at risk’ Warlpiri individuals, who spend time •In Alice Springs there are four main programs set up to respond to - There is a genuine need for domestic products in the reconnecting with the land, learning Indigenous culture, volatile substance misuse: general population kinship connections and stories. There is also total lack of supply - Therefore can’t simply prohibit use Table 1: Primary responding programs in Alice Springs and their main roles - VS users are often coerced by the Yuendumu community and family groups to attend treatment at the outstation • Since 2002 new legislation has given police greater powers for Programs Main Roles responding to volatile substance misuse (VSM). Central Australian Youth Link -

Volatile Substance Misuse a Review of Interventions

Volatile Substance Misuse: A Review of Interventions A Substance Misuse: Volatile Volatile Substance Misuse: a review of interventions Monograph Series No. 65 VOLATILE SUBSTANCE MISUSE: A REVIEW OF INTERVENTIONS Peter d’Abbs James Cook University and Sarah MacLean Youth Research Centre at the University of Melbourne ISBN: 1 74186 533 6 Online ISBN: 1 74186 534 4 Publications Number: P3-3327 Print Copyright © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Online Copyright © Commonwealth of Australia 2008 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Canberra ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Contents | iii Contents List of tables ...........................................................................................................vi -

Northern Territory of Australia and PSMA Australia

126° 128° 130° 132° 134° 136° 138° SOURCES This map has been compiled by Spatial Vision from data supplied by the Australian Electoral Commission, Geoscience Australia, Northern Territory of Australia and PSMA Australia. The source of data, other than Electoral Division boundaries, is data from PSMA Australia, Geoscience Australia and the Northern Territory of Australia. DISCLAIMER This map has been compiled from various sources and the publisher and/or contributors accept no responsibility for any injury, loss or damage arising from its use or errors or omissions therein. While all care is taken to ensure a high degree of accuracy, users are invited to notify of -10° any map discrepancies. © Commonwealth of Australia (2020) © Northern Territory of Australia (2020) ARAFURA SEA -10° Administrative Boundaries ©PSMA Australia Limited licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Copyright Officer, Education and Communications Branch, Australian Electoral Commission, Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 or to Croker Island [email protected] Minjilang Melville Island Milikapiti (Snake Bay) Wessel Islands Pirlangimpi Christmas Island (Garden Point) Cocos (Keeling) Bathurst Island TIWI ISLANDS Warruwi Islands Nguiu -

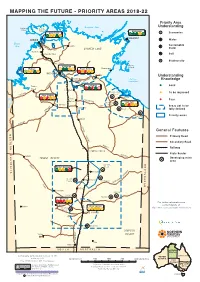

Mapping the Future – Priority Areas for 2018-2022

MAPPING THE FUTURE - PRIORITY AREAS 2018-22 Priority Area Arafura Sea Understanding Bathurst Melville Island Island Nhulunbuy $ Economics Gunn Point $ $ NHULUNBUY DARWIN Water Timor Sustainable Sea ARNHEM Jabiru Yield HWY ARNHEM LAND Batchelor Adelaide River Soil Biodiversity Pine Creek Groote Katherine Eylandt Wadeye $ Roper Valley Numbulwar $ $ KATHERINE Ngukurr Understanding Mataranka Gulf of Knowledge HIGHWAY Carpentaria ROPER Timber Larrimah Good HIGHWAY Creek $ Larrimah Coppermine To be improved Creek VICTORIA Sturt Plateau $ Borroloola Daly CARPENTARIA Poor Waters McArthur Gulf Fall Top Springs River $ HWY Areas yet to be Dunmarra Merlin fully defined HIGHWAY Stanton Priority areas Elliott BUNTINE STUART General Features W E S T E R N HIGHWAY Primary Road Secondary Road BARKLY Railway TENNANT CREEK A U S T R A L I A HIGHWAY State Border Tanami TANAMI DESERT Developing mine area TANAMI Hatches Western Davenport Creek $ Ali Curung HIGHWAY Mount Barrow Creek Peake Ammaroo SANDOVER ROAD Q U E E N S L A N D Ti-Tree Yuendumu Jervois Nolans Molyhil Arid Zone $ STUART For further information see Papunya contact details at: Kintore Alice Springs http://denr.nt.gov.au/mapping-the-future Charley $ Creek ALICE SPRINGS Chandler SIMPSON HIGHWAY Yulara DESERT Finke Kulgera S O U T H A U S T R A L I A NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Cartography by Geospatial Services, DENR WESTERN February 2019 kilometres 0 100 200 300 AUSTRALIA 400 kilometres SOUTH File: DENR2018024_MtF_PriorityAreas AUSTRALIA NEW SOUTH Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Projection - Lamberts Conformal Conic WALES International Public License Standard Parallels 23^20’00"S & 12^40’00"S (CC BY 4.0) Horizontal Datum GDA 94 VICTORIA https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode Department of Environment and Natural Resources TASMANIA C Northern Territory Government . -

Newmont Tanami Operations | Social Impact Assessment I

Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining 4 April 2019 Newmont Tanami Operations Social Impact Assessment The University of Queensland Ranked in the world's top 501, The University of Queensland (UQ) is one of Australia's leading research and teaching institutions. UQ strives for excellence through the creation, preservation, transfer and application of knowledge. For more than a century, we have educated and worked with outstanding people to deliver knowledge leadership for a better world. Sustainable Minerals Institute The Sustainable Minerals Institute (SMI) is a world-leading research2 institute committed to developing knowledge-based solutions to the sustainability challenges of the global resource industry, and to training the next generation of industry and community leaders. The Institute is transdisciplinary, and our work is independent, impartial and rigorous. Our research integrates the expertise of production, environmental and social science specialists to deliver responsible resource development. Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining The Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining (CSRM) focuses on the social, cultural, economic and political challenges that occur when change is brought about by mineral resource extraction. The Centre contributes to industry change through independent research, teaching and by convening and participating in multi- stakeholder dialogue processes. The team consist of anthropologists, sociologists, political scientists, economists, engineers, development and natural resource specialists. CSRM study team Centre director Professor Deanna Kemp Director, CSRM Authors Dr Anthony Kung Senior Research Fellow (study director from Dec 2018) Dr Paul Rogers Research Fellow (project manager) Dr Emilia Skrzypek Research Fellow Mr Rodger Barnes Research Manager Lead reviewer Professor John Owen Deputy Director, CSRM Senior reviewers Assoc.