SAHS Transactions XXXVIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Document

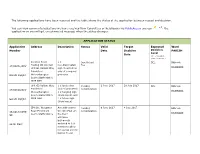

The following applications have been received and the table shows the status of the application between receipt and decision. You can view comments/objections we have received from Consultees or Neighbours via PublicAccess and can the application so you will get an automated message when the status changes. APPLICATION STATUS Application Address Description Status Valid Target Expected Ward Number Date Decision Decision PARISH Level Date (DEL – Delegated) (COM – Committee) Eurofins Food 1 x Insufficient DEL Bilbrook 17/00251/ADV Testing UK Limited non-illuminated Fee Unit G1 Valiant Way sign mounted on BILBROOK Pendeford side of company Gareth Dwight Wolverhampton premises South Staffordshire WV9 5GB Unit G2 Valiant Way 1 x fascia sign Pending 2 June 2017 28 July 2017 DEL Bilbrook 17/00510/ADV Pendeford (non-illuminated) Consideration Wolverhampton 1 x hanging sign BILBROOK South Staffordshire (illuminated) and Gareth Dwight WV9 5GB 1 x totem sign (illuminated) I54 Site Wobaston Amendments to Pending 6 June 2017 4 July 2017 Bilbrook 16/00187/AME Road Pendeford the Site Plan are Consideration South Staffordshire the front BILBROOK ND entrance bell-mouth Sarah Plant widened to 6.8 meters to allow for access control barrier to car park, rear sprinkler tank position amended, rear car park alignment adjusted and swales to South East of site removed. Amendments to the Elevations are the feature goalpost colour amending from Chilli Red to Anthracite and the rear sprinkler tank added. Eurofins Food Door position on Application Bilbrook 17/00002/AME Testing UK Limited proposed north Invalid On Receipt BILBROOK ND2 Unit G1 Valiant Way elevation moved Pendeford to suit client Wolverhampton operational Jennifer Mincher South Staffordshire requirements. -

Proposed South Staffordshire Housing Strategy Public Consultation Key Points for Residents in Wordsley, Kingswinford and Wall Heath

Proposed South Staffordshire Housing Strategy Public Consultation Key Points for residents in Wordsley, Kingswinford and Wall Heath South Staffordshire Council (SSC) want to build groups of 500 to 2,500 houses along the western edge of the conurbation between Stourbridge and Wolverhampton. Proposed areas include the green fields (green belt) around Wordsley, Kingswinford and Wall Heath along the A449. It includes the fields around The Roe Deer pub and the fields behind the Ashwood Park estate (Friars Gorse). View the proposals at https://bit.ly/2XDw7c4 see Spatial Housing Strategy October 2019 (Option G) South Staffordshire Council are now asking for feedback on their new housing proposals. Action Needed: Write to South Staffordshire Council by 12th December If you are concerned about these proposals please make comments or objections by 5pm Thursday 12th December 2019 by email, letter or online response form. See “Points to include” below for ideas to help you write your objection. • Email: [email protected] • Post: Local Plans Team, Council Offices, Codsall, South Staffordshire, WV8 1PX • Online: Response Form https://bit.ly/35l3tzl (to be printed and emailed) Remember to: • Use a heading eg SSC Local Plan Review or Green Belt Concerns SSC Housing Strategy • Include your name and address • Keep it simple and write clearly • Put your objections in your own words, avoid copying responses word for word Numbers of responses are crucial. Submit responses individually rather than as a couple/family. Points to include 1. Loss of green belt • It is better to use old factory sites and re-develop inner-cities to revive town centres. -

Kinver Neighbourhood Plan First Consultation Issues and Options Appendices

Kinver Neighbourhood Plan First Consultation Issues and Options Appendices. Appendix 1. What is a Neighbourhood Development Plan? 1.1 Neighbourhood Development Plans (NDPs) were introduced through the Localism Act 2011 to give local people a greater say in planning decisions that affect their area. NDPs are neighbourhood level planning policy documents with policies designed to reflect the needs and priorities of local communities. 1.2 NDPs can identify where development should take place, set out local design principles so that buildings respond positively to local character, and protect important facilities, historic buildings, the natural environment and open spaces. Made (adopted) NDPs are part of the local statutory development plan for their area. Planning applications are determined in accordance with the Neighbourhood Plan unless ‘material considerations’ indicate otherwise. (‘Material Considerations’ are factors provided for in planning law, such as Highway safety and access, capacity of local infrastructure, effects on listed buildings, loss of light or privacy etc.; and higher-level planning policies including emerging policies). 1.3 A Neighbourhood Development Plan (NDP) can cover a range of planning related issues. This document has been prepared as a first step in setting out the possible scope and range of planning issues the Kinver NDP could cover and potential policy options for addressing these issues. 1.4 It is important to remember that our Plan has to be ‘in general conformity’ with higher-level strategic planning policies. This means it has to sit within the strategic policies in the South Staffordshire Core Strategy, adopted in 2012 and accompanying policies maps1, and cannot provide for less new housing than allocated in the South Staffordshire Local Plan. -

Agenda Document Pack

TO:- Planning Committee Councillor Terry Mason , Councillor Matt Ewart , Councillor Penny Allen , Councillor Len Bates B.E.M. , Councillor Chris Benton , Councillor Barry Bond , Councillor Mike Boyle , Councillor Jo Chapman , Councillor Bob Cope , Councillor Brian Cox , Councillor Isabel Ford , Councillor Rita Heseltine , Councillor Lin Hingley , Councillor Diane Holmes , Councillor Janet Johnson , Councillor Michael Lawrence , Councillor Roger Lees J.P. , Councillor Dave Lockley , Councillor Robert Reade , Councillor Robert Spencer , Councillor Christopher Steel Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Planning Committee will be held as detailed below for the purpose of transacting the business set out below. Date: Tuesday, 21 April 2020 Time: 18:30 Venue: Virtual meetiing D. Heywood Chief Executive A G E N D A Part I – Public Session 1 Minutes 3 - 8 2 Apologies To receive any apologies for non-attendance. 3 Declarations of Interest To receive any declarations of interest. 4 Determination of Planning Applications 9 - 76 Report of Development Management Team Manager 5 Monthly Update Report 77 - 88 Report of the Lead Planning Manager Page 1 of 88 RECORDING Please note that this meeting will be recorded. PUBLIC SPEAKING Please note: Any members of the public wishing to speak must confirm their intention to speak in writing or e-mail to Development Management no later than 1 working day before the Committee i.e. before 12.00 p.m. on the preceding Monday. E-mails to [email protected] Please see Speaking at Planning Committee leaflet on the website for full details. Failure to notify the Council of your intention to speak may mean you will not be allowed to speak at Committee. -

Cavendish Square

DRAFT CHAPTER 7 Cavendish Square Peering over the railings and through the black trees into the garden of the Square, you see a few miserable governesses with wan-faced pupils wandering round and round it, and round the dreary grass-plot in the centre of which rises the statue of Lord Gaunt, who fought at Minden, in a three- tailed wig, and otherwise habited like a Roman Emperor. Gaunt House occupies nearly a side of the Square. The remaining three sides are composed of mansions that have passed away into dowagerism; – tall, dark houses, with window-frames of stone, or picked out of a lighter red. Little light seems to be behind those lean, comfortless casements now: and hospitality to have passed away from those doors as much as the laced lacqueys and link-boys of old times, who used to put out their torches in the blank iron extinguishers that still flank the lamps over the steps. Brass plates have penetrated into the square – Doctors, the Diddlesex Bank Western Branch – the English and European Reunion, &c. – it has a dreary look. Thackeray made little attempt to disguise Cavendish Square in Vanity Fair (1847–8). Dreariness could not be further from what had been intended by those who, more than a century earlier, had conceived the square as an enclave of private palaces and patrician grandeur. Nor, another century and more after Thackeray, is it likely to come to mind in what, braced between department stores and doctors’ consulting rooms, has become an oasis of smart offices, sleek subterranean parking and occasional lunch-hour sunbathing. -

Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire

Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Clent and Lickey Hills Area Landscape Value Study June 2019 Prepared by Carly Tinkler CMLI and CFP for CPRE Worcestershire Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Clent and Lickey Hills Area Landscape Value Study Technical Report Prepared for CPRE Worcestershire June 2019 Carly Tinkler BA CMLI FRSA MIALE Community First Partnership Landscape, Environmental and Colour Consultancy The Coach House 46 Jamaica Road Malvern 143-145 Worcester Road WR14 1TU Hagley, Worcestershire [email protected] DY9 0NW 07711 538854 [email protected] 01562 887884 Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Document Version Control Version Date Author Comment Draft V1 14.06.2019 CL / CT Issued to CPREW for comment Draft V1 02.07.2019 CL / CT Minor edits Final 08.07.2019 CL / CT Final version issued to CPREW for publication Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Contents Page number Acronyms 1 Introduction 1 2 Landscape Value 4 3 Method, Process and Approach 15 4 Landscape Baseline 21 5 Landscape Value Study Results 81 6 Conclusions and Recommendations 116 Appendices Appendix A: Figures Appendix B: Landscape Value Study Criteria Figures Figure 1: Study Area Figure 2: Landscape Value Study Zones Figure 3: Former Landscape Protection Areas Figure 4: Landscape Baseline - NCAs and LCTs Figure 5: Landscape Baseline - Physical Environment Figure 6: Landscape Baseline - Heritage Figure 7: Landscape Baseline - Historic Landscape Character Figure 8: Landscape Baseline - Biodiversity Figure 9: Landscape Baseline - Recreation and Access Figure 10: Key Features - Hotspots Figure 11: Valued Landscape Areas All Ordnance Survey mapping used in this report is © Ordnance Survey Crown 2019. -

Gunns Mills, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement Of

Gunns Mills, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement of Significance for The Forest of Dean Buildings Preservation Trust March 2016 © Cotswold Archaeology Gunns Mills, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire: Statement of Significance Gunns Mills, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement of Significance prepared by Richard Hayman, Industrial History Specialist date February 2016 checked by Alan Ford, Senior Heritage Consultant date March 2016 approved by Alan Ford, Senior Heritage Consultant signed date March, 2016 issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. Cirencester Milton Keynes Andover Exeter Building 11 41 Burners Lane South Stanley House Unit 53 Kemble Enterprise Park Kiln Farm Walworth Road Basepoint Business Centre Cirencester Milton Keynes Andover Yeoford Way Gloucestershire Buckinghamshire Hampshire Marsh Barton Trading Estate GL7 6BQ MK1 3HA SP10 5LH Exeter EX2 8LB t. 01285 771022 t. 01908 564660 t. 01264 347630 t. 01392 826185 f. 01285 771033 e. [email protected] © Cotswold Archaeology Gunns Mills, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire: Statement of Significance CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL -

Richard Morton (1637-1698)*

RICHARD MORTON (1637-1698)* by R. R. TRAIL RICHARD MORTON, the first physician since Galen to envisage a concept of the unity of tuberculosis and the first physician ever to state that tubercles are always present in its pulmonary form, was born in the county of Suffolk and baptised on 30 July 1637 in the parish of Ribbesford, Worcestershire, where his father, Robert Morton, was minister of Bewdley Chapel from 1635 to 1646. Richard Morton matriculated from Magdalen Hall, Oxford, but moved to New College when Magdalen Hall was ab- sorbed by Magdalen College. He graduated Bachelor of Arts on 30 January 1656, and Master of Arts on 8 July 1659. During the interval he was Chaplain to New College and must have had the opportunity of meeting Sydenham, who held his Fellowship of All Souls until some time around 1661. Shortly afterwards he became Chaplain to the family of Philip Foley of Prestwood, and vicar of the parish of Kinver in Worcestershire. Philip Foley was his cousin, the fourth son of Thomas Foley, ironmaster at Stourbridge, and at various times between 1673 and 1701 Member of Parliament for Bewdley, Stafford and Droitwich. The founder of the family, which Munk describes as 'old and highly respectable', was Richard Foley, a seller of nails, and later a forgemaster, who had settled in Stourbridge in 1627, when he bought the manor of Bedcote from John Sparry. According to Scrivenor's History of the Iron Trade (1841) he had built his splitting mills on drawings of the ironfoundries in Sweden, to which he had gained entrance on the pretence that he was entertaining the workers on his fiddle. -

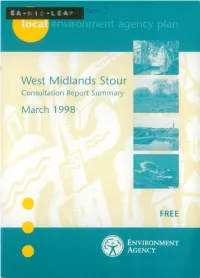

West Midlands Stour Consultation Report Summary

West Midlands Stour Consultation Report Summary March 1998 'O FREE y-- Wolverhampton ^ Bridgnorth DC f \ Wolverhampton & * MBC Dudley_ r 2 ^ ' ' V - * y South'^ Staffordshire DC SHROPSHIRE CC I ,1 Kinver I f * J ^ r ‘K y/ ,jJs v^Lj* Ir* #\ ft k v t P 's ^> -----^ X f Wesl Ha9|eyHagtey W -\VSS^ ^ - Broms9roisgrove DC/ \ / £ * of^*t D C .^ > C - "\ V V HERtfrORD ) i S . / T \ Vy M a p 1 Main Rivers, Administrative Boundaries and Infrastructure S%T\ < Stourport KEY Area Boundary — Motorway --- Main River Main Road --- Ordinary Watercourse — Railway --- Canal “ County boundary S S I Built up Area --- District boundary — — Metropolitan Borough boundary Copyright Waiver Thii report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgment is given to the Environment Agency. We Need Your Views Local Environment Agency Plans (LEAPs) rely on the opinions of individuals and organisations who have an interest in the protection and enhancement of the local environment. This booklet is a summary of the full Consultation Report which is available from the Environment Agency and local libraries. If you have any comments about the information and issues contained in the LEAP or views on the future management of the area, we would like to hear from you. You can let us know your views by filling in the questionnaire on the centre pages of this booklet and returning it in the pre-paid envelope provided, or by writing to: Nicola Pinnington Comments are required by: LEAPS Officer 19th June 1998 The Environment Agency Further copies of this booklet and the Hafren House full Consultation Report are available at Welshpool Road the above address. -

West Midland Bird Club

West Midland Bird Club Annual Report No 40 1973 The front cover shows a male Pied Flycatcher with food. This species is a scarce nesting bird in the Club's area. The main feature article of this year's Report deals with the distribution of the Rook and the illustration below shows this familiar bird at its nest. West Midland Bird Club Annual Report No 40 1973 Being the Annual Bird Report of the West Midland Bird Club on the birds of Warwickshire, Worcestershire and Staffordshire. Contents 2 Officers and Committee 3 Chairman's Remarks 3 Editor's Report 5 Secretary's Report 6 Treasurer's Report and Financial Statement 8 Membership Secretary's Report 8 Ringing Secretary's Report 9 Field Meetings Report 9 Conservation Officer's Report 10 Ladywalk Reserve 11 The Rookeries of Warwickshire, Worcestershire and Staffordshire 22 Classified Notes 77 Recoveries in 1973 of Birds Ringed in the WMBC area 83 Recoveries in WMBC area of Birds Ringed elsewhere 85 Arrival and Departure of Migrants 85 Key to Contributors 95 List of Species requiring descriptions Price 50p 2 Officers and Committee 1974 President The Lord Hurcomb, GCB, KBE Vice-President A J Harthan, Dovers Cottage, Weston Subedge, Chipping Camden, Gloucestershire Vice-President C A Norris, Brookend House, Wetland, Worcestershire Chairman A T Clay, " Ardenshaw," Ullenhall, Solihull, Warwickshire B95 5RW Secretary A J Richards, 1 St. Asaph's Avenue, Studley, Warwickshire B80 7JB Editor B R Dean, 2 Charingworth Road, Solihull, Warwickshire B92 8HT Treasurer K H Thomas, 34 Froxmere Close, Crowle, -

Gunns Mill, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement Of

Gunns Mill, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement of Significance for The Forest of Dean Buildings Preservation Trust March 2016 © Cotswold Archaeology Gunns Mill, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire: Statement of Significance Gunns Mill, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire Statement of Significance prepared by Richard Hayman, Industrial History Specialist date February 2016 checked by Alan Ford, Senior Heritage Consultant date March 2016 approved by Alan Ford, Senior Heritage Consultant signed date August, 2016 issue 02 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. Cirencester Milton Keynes Andover Exeter Building 11 41 Burners Lane South Stanley House Unit 53 Kemble Enterprise Park Kiln Farm Walworth Road Basepoint Business Centre Cirencester Milton Keynes Andover Yeoford Way Gloucestershire Buckinghamshire Hampshire Marsh Barton Trading Estate GL7 6BQ MK1 3HA SP10 5LH Exeter EX2 8LB t. 01285 771022 t. 01908 564660 t. 01264 347630 t. 01392 826185 f. 01285 771033 e. [email protected] © Cotswold Archaeology Gunns Mill, Flaxley, Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire: Statement of Significance CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND -

F .T . DIC. KINSON, " HENRY ST. JOHN and the STRUGGLE FOR

f .T . DIC.KINSON, " HENRY ST. JOHN AND THE STRUGGLE FOR THE LEADERSHIP OF THE TORY PAR'.i'Y 1702-14" Volume Two. Chapter Eight. The Emerging Rival to Harley. The supreme political skill and management of Harley had engineered. the ministerial revolution of 1710, but he had not been able to prevent a large and potentially unruly Tory majority in the Commons. Though Harley had the support, if not the absolute allegiance, of many Tory leaders, including Bromley, Rochester, St. John, and Harcourt, there were already those who opposed his trimming policy. The most important of these was the earl of Nottingham, whose integrity and high Church principles commanded widespread respect in the Tory ranks. Kept out of the ministry he appeared a potential rallying point for those Tories disgruntled with Harley's. moderate policy. As early as 28 October 1710 his lieutenant, John Ward, was trying to recruit a party for him and was 1 hoping to enlist Sir Thomas Harmer. The duke of Shrewsbury warned Harley that many other peers, besides Nottingham, were dissatisfied and he listed Argyll, Rivera, Peterborough, Jersey, Fitzwalter, 2 Guernsey, and Haversham. There were soon reports that the 1 Leicester Record Office. Finch bliss. Box vi, bundle 23. Ward to Nottingham, 28 Oct. 1710. 2 H. N. C. Bath Mss. 1,199.20 Oct. 1710. , , - 435 - 3 ministers would fall out among themselves. Despite all these manifestations of early trouble Harley pressed on with his plans to reduce faction at home and secure peace abroad. The essential prerequisite was to restore financial confidence, a task more 4 difficult than the Tory backbenchers ever realised.