Global Ecology and Conservation the Contribution Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List

2021 Santa Barbara Zoo Reciprocal List – Updated July 1, 2021 The following AZA-accredited institutions have agreed to offer a 50% discount on admission to visiting Santa Barbara Zoo Members who present a current membership card and valid picture ID at the entrance. Please note: Each participating zoo or aquarium may treat membership categories, parking fees, guest privileges, and additional benefits differently. Reciprocation policies subject to change without notice. Please call to confirm before you visit. Iowa Rosamond Gifford Zoo at Burnet Park - Syracuse Alabama Blank Park Zoo - Des Moines Seneca Park Zoo – Rochester Birmingham Zoo - Birmingham National Mississippi River Museum & Aquarium - Staten Island Zoo - Staten Island Alaska Dubuque Trevor Zoo - Millbrook Alaska SeaLife Center - Seaward Kansas Utica Zoo - Utica Arizona The David Traylor Zoo of Emporia - Emporia North Carolina Phoenix Zoo - Phoenix Hutchinson Zoo - Hutchinson Greensboro Science Center - Greensboro Reid Park Zoo - Tucson Lee Richardson Zoo - Garden Museum of Life and Science - Durham Sea Life Arizona Aquarium - Tempe City N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher - Kure Beach Arkansas Rolling Hills Zoo - Salina N.C. Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores - Atlantic Beach Little Rock Zoo - Little Rock Sedgwick County Zoo - Wichita N.C. Aquarium on Roanoke Island - Manteo California Sunset Zoo - Manhattan Topeka North Carolina Zoological Park - Asheboro Aquarium of the Bay - San Francisco Zoological Park - Topeka Western N.C. (WNC) Nature Center – Asheville Cabrillo Marine Aquarium -

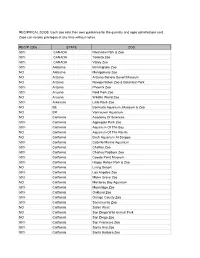

2006 Reciprocal List

RECIPRICAL ZOOS. Each zoo sets their own guidelines for the quantity and ages admitted per card. Zoos can revoke privileges at any time without notice. RECIP 2006 STATE ZOO 50% CANADA Riverview Park & Zoo 50% CANADA Toronto Zoo 50% CANADA Valley Zoo 50% Alabama Birmingham Zoo NO Alabama Montgomery Zoo NO Arizona Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum NO Arizona Navajo Nation Zoo & Botanical Park 50% Arizona Phoenix Zoo 50% Arizona Reid Park Zoo NO Arizona Wildlife World Zoo 50% Arkansas Little Rock Zoo NO BE Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo NO BR Vancouver Aquarium NO California Academy Of Sciences 50% California Applegate Park Zoo 50% California Aquarium Of The Bay NO California Aquarium Of The Pacific NO California Birch Aquarium At Scripps 50% California Cabrillo Marine Aquarium 50% California Chaffee Zoo 50% California Charles Paddock Zoo 50% California Coyote Point Museum 50% California Happy Hollow Park & Zoo NO California Living Desert 50% California Los Angeles Zoo 50% California Micke Grove Zoo NO California Monterey Bay Aquarium 50% California Moonridge Zoo 50% California Oakland Zoo 50% California Orange County Zoo 50% California Sacramento Zoo NO California Safari West NO California San Diego Wild Animal Park NO California San Diego Zoo 50% California San Francisco Zoo 50% California Santa Ana Zoo 50% California Santa Barbara Zoo NO California Seaworld San Diego 50% California Sequoia Park Zoo NO California Six Flags Marine World NO California Steinhart Aquarium NO CANADA Calgary Zoo 50% Colorado Butterfly Pavilion NO Colorado Cheyenne -

Black-Footed Ferret Media

coming soon to Canada The black-footed ferret returns to the Canadian prairies The black-footed ferret is one of North America’s most endangered animals and just a few decades ago, was thought to be extinct. Now after several years of international effort, the black-footed ferret will be reintroduced into the wild in Canada in Fall 2009. In 2004, the Toronto Zoo, in partnership with Parks Canada, US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), Calgary Zoo, private stakeholders and other organizations established a joint Black-footed Ferret/Black-tailed Prairie Dog Canadian Recovery Team to look at the potential for reintroducing black-footed ferrets into Grasslands National Park (GNP) in Saskatchewan. After a lot of hard work on many levels, reintroduction of black-footed ferrets into black-footed ferret kits GNP is now planned for the fall of 2009. 4 spring 2009 collections back from near-extinction The black-footed ferret is the only native ferret known to North America and is listed as one of North America’s most endangered species. Ferrets prey almost exclusively on prairie dogs and inhabit prairie dog burrows. Loss of prairie dogs due to wide-scale extermination, agricultural conversion of their habitat, and epidemics of sylvatic plague (black plague) have resulted in the loss of about 95% of the ferret range since the 1800s. The black-footed ferret was thought to be extinct in the mid 1970s but in 1981 there was a dramatic discovery of a small population in Meetetse, Wyoming. Between 1985 and 1987, 18 ferrets were brought into captivity for the purpose of setting up a captive breeding and reintroduction program to save the species. -

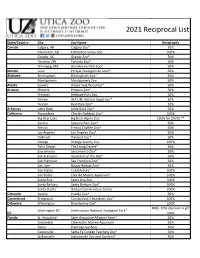

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact

Updated March 25th, 2021 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Katie Frost 403-232-9386 Granby - Quebe Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept 416-392-9101 Winnipeg - ManiAssiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 If the zoo or aquarium to which MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 you belong has 50% in the Reciprocity column, you can Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 expect to receive a 50% discount Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 on admission at all the zoos and Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept 602-914-4393 aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are FREE TO Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept 877-526-3960 THE PUBLIC). Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept 520-881-4753 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 If the zoo or aquarium to which California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 you belong has 100% and 50% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 in the Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive free Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office559-498-5921 admission to the zoos and Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept 323-644-4759 aquariums that also have 100% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Membership Dept 510-632-9525 x160 and 50% in the Reciprocity column and those that are FREE Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Elisa Escobar 760-346-5694 x2111 TO THE PUBLIC; and a 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% Membership Dept 916-808-5888 discount on admission to the San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% Jaz Cariola 415-623-5310 zoos and aquariums that have 50% in the Reciprocity column. -

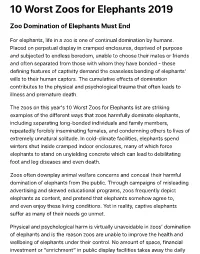

10 Worst Zoos for Elephants 2019

10 Worst Zoos for Elephants 2019 Zoo Domination of Elephants Must End For elephants, life in a zoo is one of continual domination by humans. Placed on perpetual display in cramped enclosures, deprived of purpose and subjected to endless boredom, unable to choose their mates or friends and often separated from those with whom they have bonded - these defining features of captivity demand the ceaseless bending of elephants' wills to their human captors. The cumulative effects of domination contributes to the physical and psychological trauma that often leads to illness and premature death. The zoos on this year's 10 Worst Zoos for Elephants list are striking examples of the different ways that zoos harmfully dominate elephants, including separating long-bonded individuals and family members, repeatedly forcibly inseminating females, and condemning others to lives of extremely unnatural solitude. In cold-climate facilities, elephants spend winters shut inside cramped indoor enclosures, many of which force elephants to stand on unyielding concrete which can lead to debilitating foot and leg diseases and even death. Zoos often downplay animal welfare concerns and conceal their harmful domination of elephants from the public. Through campaigns of misleading advertising and skewed educational programs, zoos frequently depict elephants as content, and pretend that elephants somehow agree to, and even enjoy these living conditions. Yet in reality, captive elephants suffer as many of their needs go unmet. Physical and psychological harm is virtually unavoidable in zoosʼ domination of elephants and is the reason zoos are unable to improve the health and wellbeing of elephants under their control. No amount of space, financial investment or “enrichment” in public display facilities takes away the daily pain that zoo captivity inflicts on elephants. -

Organization City State Admission Additional Discount

Organization City State Admission Additional Discount Calgary Zoo Calgary - Alberta Canada 50% Granby Zoo Granby - Quebec Canada 50% Toronto Zoo Toronto - Ontario Canada 50% Parque Zoologico de Leon Leon Mexico 50% Birmingham Zoo Birmingham Alabama 50% Alaska SeaLife Center Seward Alaska 50% The Phoenix Zoo Phoenix Arizona 50% Reid Park Zoo Tucson Arizona 50% Little Rock Zoo Little Rock Arkansas 50% Charles Paddock Zoo Atascadero California 50% Sequoia Park Zoo Eureka California 50% Fresno Chaffee Zoo Fresno California 50% Los Angeles Zoo Los Angeles California 50% Oakland Zoo Oakland California 50% The Living Desert Palm Desert California 50% Sacramento Zoo Sacramento California 50% Aquarium of the Bay San Francisco California 50% San Francisco Zoo San Francisco California 50% Happy Hollow Zoo San Jose California 50% CuriOdyssey (Coyote Point Museum) San Mateo California 50% Cabrillo Marine Aquarium San Pedro California FREE 10% discount at gift shop Santa Ana Zoo Santa Ana California 50% Santa Barbara Zoo Santa Barbara California 50% Pueblo Zoo Pueblo Colorado 50% Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo Bridgeport Connecticut 50% Smithsonian's National Zoological Park Washington DC DC FREE 10% discount at gift shops on-site Brandywine Zoo Wilmington Delaware 50% Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens Jacksonville Florida 50% Brevard Zoo Melbourne Florida 50% Zoo Miami Miami Florida 50% Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens Sanford Florida 50% Mote Marine Aquarium Sarasota Florida 50% Saint Augustine Alligator Farm St. Augustine Florida 50% The Florida Aquarium -

2021 Reciprocal List

2021 Reciprocal List State/Country City Zoo Name Reciprocity Canada Calgary, AB Calgary Zoo* 50% Edmonton, AB Edmonton Valley Zoo 100% Granby, QC Granby Zoo* 50% Toronto, ON Toronto Zoo* 50% Winnipeg, MB Assiniboine Park Zoo* 50% Mexico Leon Parque Zoologico de Leon* 50% Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo* 50% Montgomery Montgomery Zoo 50% Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center* 50% Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo* 50% Prescott Heritage Park Zoo 50% Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium* 50% Tuscon Reid Park Zoo* 50% Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo* 50% California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo* 100% Big Bear Lake Big Bear Alpine Zoo 100% for 2A/3C ** Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo* 50% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo* 50% Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo* 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo* 50% Orange Orange County Zoo 100% Palm Desert The Living Desert* 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo* 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay* 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo* 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo* 50% San Mateo CuriOdyssey* 100% San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium* 100% Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo 100% Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo* 100% Santa Clarita Gibbon Conservation Center 100% Colorado Pueblo Pueblo Zoo* 50% Connecticut Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo* 100% Delaware Wilmington Brandywine Zoo* 100% FREE- 10% discount in gift Washington DC Smithsonian National Zoological Park* DC shop Florida St. Augustine Saint Augustine Alligator Farm* 50% Clearwater Clearwater Marine Aquarium 50% Davie Flamingo Gardens 50% Gainesville Santa Fe College Teaching Zoo* 50% Jacksonville Jacksonville -

Roger Williams Park Zoo's Membership Reciprocal List

Roger Williams Park Zoo’s Membership Reciprocal List As of January 1, 2016, your Roger Williams Park Zoo reciprocal benefit is good for 50% off admission to the zoos, aquariums and museums listed below. Please note that the number of visitors admitted with a family membership may vary and parking may not be included. Always call ahead! Updated January 2021 Canada Calgary Zoo - Calgary, Alberta Granby Zoo - Granby, Quebec Toronto Zoo - Toronto Mexico Parque Zoológico de León, Leon United States Alabama Birmingham Zoo Alaska Alaska SeaLife Center, Seward Arizona The Phoenix Zoo SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium, Tempe Reid Park Zoo, Tucson Arkansas Little Rock Zoo California Aquarium of the Bay, San Francisco Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, San Pedro (Free to the Public) Charles Paddock Zoo, Atascadero CuriOdyessy, San Mateo Fresno Chaffee Zoo, Fresno Happy Hollow Zoo, San Jose Los Angeles Zoo Oakland Zoo Sacramento Zoo San Francisco Zoo Santa Ana Zoo Santa Barbara Zoo Sequoia Park Zoo, Eureka The Living Desert, Palm Desert Colorado Pueblo Zoo Connecticut Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo, Bridgeport Mystic Aquarium ($2 Discount off General Admission Tickets) Delaware Brandywine Zoo, Wilmington Florida Brevard Zoo, Melbourne Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens, Sanford The Florida Aquarium, Tampa Jacksonville Zoo & Gardens Mote Marine Aquarium, Sarasota Palm Beach Zoo Alligator Farm Zoological Park, St. Augustine Tampa’s Lowry Park Zoo Zoo Miami Georgia Chehaw Wild Animal Park, Albany Zoo Atlanta Idaho Idaho Falls Zoo at Tautphaus Park, Idaho Falls Zoo -

North American Regional Snow Leopard Studbook

North American Regional Snow Leopard Studbook UNCIA UNCIA 2014 Lynn Tupa ABQ BioPark 903 Tenth St. SW Albuquerque, NM 87102-4098, USA [email protected] 505-764-6216 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to all of the individuals and institutions that provided me the regular updates needed to complete the 2014 regional studbook. Without the information you all provided the studbook would not be possible. I’d like to thank the ABQ BioPark for their continued support of me as the Regional Snow Leopard Studbook Keeper. A special thanks to Jennifer Vanorman for the use of her photos of Bhutan the snow leopard born at the Albuquerque Biological Park in July 2008. A thank you to Jay Tetzloff Species Coordinator of the Snow Leopard and the rest of the Steering Committee for all of their hard work during the Master Planning sessions for the snow leopard. A final Thank you to Leif Blomqvist, International Snow Leopard Studbook Keeper, for continuing to provide current updates to the studbook. Without his help the accuracy of this studbook would not be possible. If any institution or individual would like to make corrections or additions to the studbook, please send your data to Lynn Tupa at [email protected], or ABQ BioPark, 903 Tenth St. SW, Albuquerque NM 87102, 505-764-6216 (office) 505-764- 6281 (fax). ii iii Table of Contents Section Page Scope of the Studbook 1 Status of the population 1 Description of the data fields 1 Natural History 2 Living Population (by institution) 3 AKRON – Akron Zoological Park 4 ANCHORAGE – Alaska Zoo 4 BATTLE CR – Binder Park -

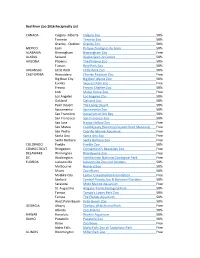

Red River Zoo 2016 Reciprocity List CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary

Red River Zoo 2016 Reciprocity List CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Granby - Quebec Granby Zoo 50% MEXICO León Parque Zoológico de León 50% ALABAMA Birmingham Birmingham Zoo Free ALASKA Seward Alaska Sea Life Center 50% ARIZONA Phoenix The Phoenix Zoo 50% Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% ARKANSAS Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% CALIFORNIA Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo Free Big Bear City Big Bear Alpine Zoo 50% Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo Free Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Lodi Micke Grove Zoo Free Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% San Francisco San Francisco Zoo 50% San Jose Happy Hollow Zoo Free San Mateo CuriOdyssey (formerly Coyote Point Museum) Free San Pedro Cabrillo Marine Aquarium Free Santa Ana Santa Ana Zoo Free Santa Barbara Santa Barbara Zoo Free COLORADO Pueblo Pueblo Zoo 50% CONNECTICUT Bridgeport Connecticut's Beardsley Zoo Free DELAWARE Wilmington Brandywine Zoo Free DC Washington Smithsonian National Zoological Park Free FLORIDA Jacksonville Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens 50% Melbourne Brevard Zoo 50% Miami Zoo Miami 50% Myakka City Lemur Conservation Foundation Free Sanford Central Florida Zoo & Botanical Gardens 50% Sarasota Mote Marine Aquarium Free St. Augustine Alligator Farm Zoological Park 50% Tampa Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo 50% Tampa The Florida Aquarium 50% West Palm Beach Palm Beach Zoo 50% GEORGIA Albany Chehaw Wild Animal Park Free Atlanta Zoo Atlanta 50% HAWAII Honolulu -

State City Zoo Or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone

Updated July 8th, 2020 State City Zoo or Aquarium Reciprocity Contact Name Phone # CANADA Calgary -Alberta Calgary Zoo 50% Stephenie Motyka 403-232-9312 Granby - Quebec Granby Zoo 50% Mireille Forand 450-372-9113 x2103 Toronto Toronto Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 416-392-9101 Winnipeg - Manitoba Assiniboine Park Zoo 50% Leah McDonald 204-927-6062 If the zoo or aquarium to which you MEXICO 50% David Rocha 52-477-210-2335 belong has 50% in the Reciprocity León Parque Zoológico de León column, you can expect to receive a Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% Patty Pendleton 205-879-0409 x232 50% discount on admission at all the Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% Shannon Wolf 907-224-6355 zoos and aquariums on this list (except, of course, those that are Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 602-914-4393 FREE TO THE PUBLIC). Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% Membership Dept. 877-526-3960 ALWAYS CALL AHEAD* Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% Membership Dept. 520-881-4753 If the zoo or aquarium to which you Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% Kelli Enz 501-371-4589 belong has 100% and 50% in the California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% & 50% Becky Maxwell 805-461-5080 x2105 Reciprocity column, you can expect to receive free admission to the zoos Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% & 50% Kathleen Juliano 707-441-4263 and aquariums that also have 100% Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% Membership Office 559-498-5921 and 50% in the Reciprocity column Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% Membership Dept. -

Reciprocal Zoo List

GOOD ZOO 2021 - 2022 Membership Reciprocity List Valid March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2022 Your membership with Oglebay Good Zoo includes an admission discount to the zoos and aquariums listed below. Reciprocal zoo participation is voluntary, and changes may occur. If you plan to visit one of the zoos below, we recommend contacting the zoo first to confirm your Oglebay Good Zoo membership will be honored. The number of visitors with a family membership at reciprocal zoos may vary, and parking may not be included. Admission Discounts 100% & 50% - Members receive free admission with membership card and photo identification 50% - Members receive 50% off eciprocal zoo’s admission rate with membership card and photo identification Free - Admission is free to the public (other discounts may apply) State City Zoo / Aquarium Admission Discount Phone Number Alabama Birmingham Birmingham Zoo 50% 205-879-0409 Alaska Seward Alaska SeaLife Center 50% 907-224-6355 Arizona Phoenix Phoenix Zoo 50% 602-914-4365 Tempe SEA LIFE Arizona Aquarium 50% 877-526-3960 Tucson Reid Park Zoo 50% 520-881-4753 Arkansas Little Rock Little Rock Zoo 50% 501-661-7218 California Atascadero Charles Paddock Zoo 100% 805-461-5080 x2105 Eureka Sequoia Park Zoo 100% 707-441-4263 Fresno Fresno Chaffee Zoo 50% 559-498-5921 Los Angeles Los Angeles Zoo 50% 323-644-4759 Oakland Oakland Zoo 50% 510-632-9525 x150 Palm Desert The Living Desert 50% 760-346-5694 x2111 Sacramento Sacramento Zoo 50% 916-808-5888 San Francisco Aquarium of the Bay 50% 415-623-5362 San Francisco San Francisco