1997 Scope of Competition in Telecommunications Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 1976

VOL. LXI AUSTIN, TEXAS, NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 3 Legislative Council Elects Reeves Chairman Court Backs 48 Administrators Named Volleyball Tourney Boggess Selected Residence, Transfer Rules To Regional Committees Dec. 3-4 In Austin As Vice-Chairman Glenn Reeves, superintendent of to determine the wants and needs For the third time in four years, Forty-eight Texas school admin Levelland Longview The State Girls' Volleyball Tournament will be held Dec. Saginaw public schools, was elected of schools in this. a Texas district court has upheld istrators will serve on the League's Supt. Odell Wilkes, Meadow Supt. Jon R. Tate, Sweeney 3 and 4 in Gregory Gymn Annex in Austin. chairman of the University In- A committee is to be appointed to 14 regional executive committees, Supt. Mance Park, terscholastic League Legislative the League Residence and Transfer Supt. Lamar B. Kelley, Amherst Huntsville Ticket prices for these matches are $2 for adults and $1 for study the Slide Rule contest to de assisting the regional director and students per session. There will be two sessions Friday (4 Council at its meeting in Austin termine if it is feasible to continue Rules (Article VIII, sections 13 Supt. Dean King, Sundown Brenham other regional executive commitee p.m. and 7:30 p.m.) and two session Saturday (9 a.m. and Nov. 7. that contest, or if it will be neces and 14). I members from the host institutions. Supt. Eugene Bigby, Bellvile C. N. Boggess, Harlandale Inde Denton 1p.m.) sary to design a totally new com The district judge in Denton Oct. -

Many Stars Come from Texas

MANY STARS COME FROM TEXAS. t h e T erry fo un d atio n MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER he Terry Foundation is nearing its sixteenth anniversary and what began modestly in 1986 is now the largest Tprivate source of scholarships for University of Texas and Texas A&M University. This April, the universities selected 350 outstanding Texas high school seniors as interview finalists for Terry Scholarships. After the interviews were completed, a record 165 new 2002 Terry Scholars were named. We are indebted to the 57 Scholar Alumni who joined the members of our Board of Directors in serving on eleven interview panels to select the new Scholars. These freshmen Scholars will join their fellow upperclass Scholars next fall in College Station and Austin as part of a total anticipated 550 Scholars: the largest group of Terry Scholars ever enrolled at one time. The spring of 2002 also brought graduation to 71 Terry Scholars, many of whom graduated with honors and are moving on to further their education in graduate studies or Howard L. Terry join the workforce. We also mark 2002 by paying tribute to one of the Foundations most dedicated advocates. Coach Darrell K. Royal retired from the Foundation board after fourteen years of outstanding leadership and service. A friend for many years, Darrell was instrumental in the formation of the Terry Foundation and served on the Board of Directors since its inception. We will miss his seasoned wisdom, his keen wit, and his discerning ability to judge character: all traits that contributed to his success as a coach and recruiter and helped him guide the University of Texas football team to three national championships. -

THECB Appendices 2011

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Summer 2011 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Summer 2011 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6147 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities .................................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities ........................................................................ A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges................................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges .................................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies .................................................................... A.5 Health-Related -

Athletic Handbook 2019-2020

KERMIT INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT ATHLETIC HANDBOOK 2019-2020 Charles Ross, Athletic Director/Head Football Coach 915-526-1121 [email protected] Program Mantra W.I.N. Our athletic department mantra will be WIN. I love to win and I will outwork our opponent coaches in order for that to happen. But the acronym WIN is not just about instilling the mindset to winning athletic competitions; it’s a way of life. It stands for What’s Important Now. I want our athletes living a balanced life of being a student-athlete, son/daughter, friend, and involved community member. Program Vision The purpose of Kermit Athletics is to develop an attitude of continuous growth towards character, integrity, leadership, and work ethic. The athletic department will represent KISD in the way administration expects of all teachers, coaches, students, and student-athletes. When student-athletes graduate they will be prepared to lead the past, present, and future generations. Program Mission The Kermit Athletic Department will outwork our opponents in the classroom, within our community, for KISD, and in the realm of athletics. As a department, we will implement a leadership program consisting of student athletes that will meet weekly to make team decisions. Within those meetings, I will teach them how to expand their leadership skills and how they can help grow leaders among the teams. Program Values These values are prioritized in a way that will enhance the probability of achieving the vision and mission. 1. Academics The athletic department will be committed to academic excellence. Each program will stress the importance of academic achievement per NCAA guidelines. -

School District Lays Off Teachers, Paraprofessionals

New Zion’s Chamber Music 8 Week WEEKEND 150th concert EVENTS Beginner Course PAGE 1B PAGE 1B Safe, Fun Starts $ 9/28 - 7pm 119 & 9/29 - 10am Online and Live $1.00 Classes Available www.cyoga-amelia.com 904•613•6345 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2020 / 14 PAGES, 2 SECTIONS • fbnewsleader.com Pope replaces Mullin as Nassau County manager JOHN SCHAFFNER ager. The evaluations were presented performance of every county department bananas over the treatment of animals. Special to the News-Leader during the morning meeting of the com- head, with personal notes about each. Tim makes sure problems do not hap- mission. For instance, he said of the Engineering pen. It is a tough, tough job.” Mullin Wednesday was the day for officially Commissioner Pat Edwards thanked Department’s Robert Companion, “He said new Planning Director Thad Crowe changing the guard in the Nassau County Mullin for his service in the dual roles, approaches things calmly … works tire- “knows how development needs to be Manager’s Office as the Board of County criticizing candidates who recently lessly. He developed Engineering into controlled.” And, he praised Emergency Commissioners officially approved a con- ran for the commission who attacked a fantastic department. He developed Management Director Greg Foster say- tract hiring Assistant County Manager Mullin and claimed he ran the commis- engineers who are specialists so we ing, “You know when he comes to you Taco Pope to replace Michael Mullin, sion’s actions. “He agreed to volunteer don’t have to constantly hire outside and says we have to have something, you who had been serving the dual roles of to assume the manager’s position. -

Inte Chojlast1 Leag Ue

-IB! & INTE CHOJLAST1 LEAG UE VOL. XXV AUSTIN, TEXAS, FEBRUARY, 1942 No. 6 Advises Culture Rural Pentathlon Group 1941 StateMeet Uniform Award Plus Specialization Youngest State LETTER. box and AN ASSOCIATED Colle- PERSONAL System Needed -^- giate Press release con Winner in 1940 ITEMS tains a statement from Robert War Makes Timely Sugges F. Moore, secretary of ap Rural .Girl Not Only Popular Holds The answers in this column are in M tion for Economizing on pointments at Columbia Uni In School But sense "official interpretations." Only th« City Buys Medals A Record State Executive Committee is competent League Awards versity which should be pon Straight under the rules to make official interpret** Meet tions, and the State Committee's interpre For District dered by high-school as well tations appear in the Official Notice column (By W. M. Kincaid, Principal, of THE LEAGUER. These are answers to T> ARELY getting under the inquiries which are made in the course of Burkburnett High School) as by college students. He The Board of City Development line as a senior declaimer routine correspondence with the State Office. "MF AY I SUGGEST that we says, in part: of Sweetwater recently voted From a period of historic un in 1940, Nell Ferrell won third Question: Is a high-school boy unanimously to purchase medals Vi have some state-wide rule employment, the situation changed place in the rural declamation eligible for Interscholastic League prizes to be given in and other on awards. We all under overnight to a seller's market division at the State Meet of activities if he is taking only three the District 5 Interscholastic stand the educational compli where there were more jobs than subjects and passing in all three? League meet to be held there in the League in 1940, and, so cations of giving prizes for men. -

The Tiger's Tale

sNyder high schOOl 3801 austiN ave. the tiger’s sNyder, tx 79549 tale Volume 102 SEPT. 27 2019 No. 1 Senior stays in ‘Big Apple’ during summer By Caitlyn Crane we wanted to pursue,” Tubbs said. the Tisch building. Sometimes we Editor Tubbs went into the program would go get donuts or something With nothing to do going into because she wants to pursue the- for breakfast, and then head to the the summer before her senior year, ater after high school. Tisch building. Our classes varied. Whitney Tubbs stumbled upon a “NYU has been a first choice They were like college classes. I month-long acting program that for a few years now. I figured I had had vocal performance, Broadway was at New York University. She nothing to lose. It seemed like a styles, ballet – it just kind of de- thought, “Why not?” great program,” Tubbs said. pended on the day. Then we would “I figured I had nothing to For Tubbs, the acting program go to the Kimmel building during lose,” Tubbs said. was amazing. lunch sometimes. It was free food. So, Tubbs applied and was ac- “Their number one priority was So that was nice. We usually got ge- cepted into the program. She lived to get to know you and to work lato (ice cream) after we ate lunch. on campus from July 7-Aug. 3. one on one with you,” Tubbs said. We would get gelato, and then just “I left (Snyder) a little early. I “They had great techniques. It was come back to class and we would left July 5. -

Vintef^CHOLASTIC LEAGUER

LEAGUER, vINTEF^CHOLASTIC . lfiT>t%-* * Vol. XXXIV AUSTIN, TEXAS, JANUARY, 1951 No. 5 Music Broadcast to Feature Assignments for 1951 Top Band, Orchestra, Chorus For the first time in the history State Network on January 30, KCRS ... Midland of League sponsored music broad 1951, at 2:30 p.m. KBST ._ _ Big Spring Spring Meets Listed casts, more than one organization All three of these organizations KFRO .. Longview will participate when the Texas have been consistent Division I KRIO .. .-.. McAllen The State Meet in Austin this Office. The final list will be is General, W. B. Killebrew, State Network presents the San winners in Interscholastic League KBWD . Brownwood year will include all schools for sued shortly following January 15, Principal, High School, Port the last day for paying League Arthur. Benito High School Mixed Chorus, competition for many years. The KPLT „ .— Paris merly members of the City Con 14. Freeport, Galena Park, Gal the Plainview High School Band San Benito Mixed Chorus, under KGVL Greenville ference, This is the first change membership dues, so rush any veston, Robert E. Lee (Bay- and the San Angelo High School the direction of W. Edward KGKL San Angelo in competitive alignments growing needed corrections. town), Pasadena, Texas City. Orchestra. All three organizations Hatchett, has achieved nation-wide KNOW Austin out of the recent reclassification Concerning all details relating Director General, T. W. Ogg, and the resulting plans for aboli Superintendent of Schools, will combine for a 30-minute con fame for its excellent presenta KFJZ 1 Ft. Worth to the District Meet, communicate Brazosport Independent cert over 20 stations of the Texas tions. -

Envision-Kermit-Plan-DRAFT-August

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The project team is grateful for the contributions of the residents of Kermit, Texas who gave their time, ideas, and expertise for the cre- ation of this plan. It is only with their assistance and direction that this plan gained the necessary depth to truly represent the spirit of the community, and it is with their commitment that the plan will be implemented. MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL STEERING COMMITTEE Jerry Phillips – Mayor Yvette Trevino – West Texas State Bank Bobby Slaughter – Council Member District 4 Laura Snyder – Shell Oil Norma Hernandez – Council Member District 5 Julio Pena – Citizen Connie Carpenter – Citizen CONSULTING TEAM CITY STAFF Denise Shetter – KISD RDG PLANNING & DESIGN Gabe Espino – KISD Omaha and Des Moines Frankie Davis – City Manager Oscar Pena – Citizen www.RDGUSA.com Diana Franco – City Secretary Greg Edwards – HiCrush Sylvester Alarcon – Assistant Public Works Director John Leavitt – Winkler County Golf Course Jaime Dutton – Chief of Police Shawna Doran – WesTex Community Credit Union Amy Haase, AICP Stephanie Rouse, AICP TABLE of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1: DISCOVER KERMIT 9 CHAPTER 2: GUIDING PRINCIPLES 21 Foundation CHAPTER 3: LAND USE 25 CHAPTER 4: HOUSING 51 CHAPTER 5: TRANSPORTATION 63 CHAPTER 6: PARKS 79 CHAPTER 7: COMMUNITY PRIDE 91 Elements CHAPTER 8: DOWNTOWN 99 CHAPTER 9: PUBLIC FACILITIES AND INFRASTRUCTURE 109 Next Steps CHAPTER 10: IMPLEMENTATION 123 CHAPTER 1 DISCOVER KERMIT WHY PLAN? TO CRAFT A SHARED VISION FOR A JOINT LEGAL BASIS FOR LAND USE REGULATIONS FUTURE In 1997, the Texas Legislature added Chapter establish the rules that govern how land is used 213 to the Local Government Code which allows and developed within the municipality and its ex- The Envision Kermit Plan is simply a road map to all municipalities in Texas to develop and adopt traterritorial jurisdiction. -

Go-Devil Year" in Midland, Texas^ Competing Shell Pipe Line Corporation Against 15 Other JA Companies in the Midland Area, JASHELL Was Tops

Employee relations manager Ken Looney dies June 7 Employee Relations Manager Ken He returned to Shell Pipe Line and Looney died suddenly June 7. Mr. the Head Office in 1958 as Supervisor Looney was 55 years old and would of Training. In 1963 he was named have celebrated his 30th anniversary District Superintendent of the Colo- with the Shell organization next rado City District in the West Texas month—27 of those years being with Division. In 1965 he returned to the Shell Pipe Line. Head Office as Personnel Supervisor; Mr. Looney began working for was named Supervisor of Employee Shell Pipe Line at Newton, Kansas Relations in 1966, and later Manager in 1941. In his early career he worked of the Employee Relations Depart- as Pipeliner, Leadman, Assistant ment in 1969. Maintenance Foreman, and Pipeline Mr. Looney leaves his wife, Mary Maintenance Foreman in such places Ann; two sons, Kenneth W. Jr. and as Tonkawa, Pauls Valley, Osage, Gary; a daughter, Mrs. Jean Ann and Yarna, before becoming Area Kocian, all of Houston, and father, Safety Engineer at Gushing in 1951. George A. Looney of McAlester, In 1954 he moved to the Head Okla. Office as Assistant Supervisor of Safety and Training and remained there until 1955 when he was trans- JASHELL grabs ferred to Shell Oil Company's Pacific Coast E&P Area as Safety and Train- 'company of year' Ken W. Looney ing Representative in Los Angeles. award at Midland The JASHELL, a junior achievement company counselled by Shell Pipe Line and Shell Oil Company, has been named the "Company of the Go-Devil Year" in_Midland, Texas^ Competing Shell Pipe Line Corporation against 15 other JA companies in the Midland area, JASHELL was tops. -

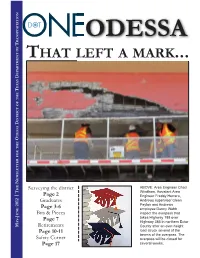

May June 2012 Layout 1

ODESSA RANSPORTATION T THAT LEFT A MARK... EPARTMENT OF D EXAS T ISTRICT OF THE D DESSA O EWSLETTER FOR THE N ABOVE: Area Engineer Chad HE Surveying the district T Page 2 Windham, Assistant Area | Engineer Freddy Herrera, Graduates Andrews supervisor Cleon 2012 Payton and Andrews Page 3-6 employee Danny Webb inspect the overpass that UNE Bits & Pieces -J Page 7 takes Highway 158 over AY Highway 385 in northern Ector M Retirements County after an over-height Page 10-11 load struck several of the beams of the overpass. The Safety Corner overpass will be closed for Page 17 several weeks. Surveying the district By Mike C. McAnally seen in 30 years and most of you are still able to District Engineer smile when I see you. Thank you very much for the dedication and professionalism you are show- It is that time again for me to have a little say in ing. this issue of the district newsletter, but I am going As dedicated and hard working as you all are, to make this a short one. I know you are all very PLEASE do not forget to take a moment before busy, and I appreciate that more than ever. performing those job duties every day and make I have been out through some of our areas, and sure that you and your co-workers are safe. Not I just want to personally thank each and every one only are the roadways busier than ever, they are of you for the outstanding jobs you are doing. -

Uncle Tom" Still Turns out League Tennis Champs

VOL. XXII AUSTIN, TEXAS, DECEMBER, 1938 No. 4 NO "ALL-ROUND" IN $5,000 DAMAGE TO FARMER COUNTY Former League Debater Extracurricular Items LETTER, Uncle Tom" Still Turns Wins Honors in College From High-School Papers bOX and Out League Tennis Champs DUVALTHIS YEAR INJUREDJUMBLER LEAGUEJETS SET OHN STEPHEN, mid-law stu 'T'HE following item found PERSONAL dent from Houston, has been ITEMS J * in high school papers | Committee Decides to Ex Calif. Supreme Court Rules "Stretch-out" Plan for Con elected Captain of the 1938-1939 about extracurricular activi periment with No-Decision Against School 'Board in ducting Non-qualifying University of Texas Intercollegi ate Debate Squad. Stephen has ties indicate wide range of IGHLAND PARK'S Golden This Year Famous Suit Contests Adopted activities in Texas high H Avalanche chalks up high been a member of the squad since scores in grade points as well as he was a freshman, having been schools: the gridiron. In spite of the UPERINTENDENT B. A. pOLLOWING is a memo A T a meeting of coaches the first freshman in the history The Bonhi, Bonham high school fact that they practice until dark Trevino's plan of elim randum written by Irving ^ and superintendents of paper: The Bonhi FFA milk judg and have to be in bed by 9:30 inating the counting of all- G. Breyer, Administrative the independent schools of the ing team won first place at the o'clock, football players average Adviser Legal Department, county in Farwell recently, Royal Livestock show in Kansas 87.7 as a team.