Two Actors on Shakespeare, Race, and Performance: a Conversation Between Harry J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with James Earl Jones

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with James Earl Jones PERSON Jones, James Earl Alternative Names: James Earl Jones; Life Dates: January 17, 1931- Place of Birth: Arkabutla, Mississippi, USA Work: Pawling, NY Occupations: Actor Biographical Note Actor James Earl Jones was born on January 17, 1931 to Robert Earl Jones and Ruth Connolly in Arkabutla, Mississippi. When Jones was five years old, his family moved to Dublin, Michigan. He graduated from Dickson High School in Brethren, Michigan in 1949. In 1953, Jones participated in productions at Manistee Summer Theatre. After serving in the U.S. Army for two years, Jones received his B.A. degree from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor in 1955. Following graduation, Jones relocated to New York City where he studied acting at the American Theatre Wing. Jones’ first speaking role on Broadway was as the valet in Sunrise at Campobello in 1958. Then, in 1960, Jones acted in the Shakespeare in Central Park production of Henry V while also playing the lead in the off-Broadway production of The Pretender. Geraldine Lust cast Jones in Jean Genet’s The Blacks in the following year. In 1963, Jones made his feature film debut as Lt. Lothar Zogg in Dr. Strangelove, directed by Stanley Kubrick. In 1964, Joseph Papp cast Jones as Othello for the Shakespeare in Central Park production of Othello. Jones portrayed champion boxer Jack Jefferson in the play The Great White Hope in 1969, and again in the 1970 film adaptation. His leading film performances of the 1970s include The Man (1972), Claudine (1974), The River Niger (1975) and The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1976). -

Festival Centerpiece Films

50 Years! Since 1965, the Chicago International Film Festival has brought you thousands of groundbreaking, highly acclaimed and thought-provoking films from around the globe. In 2014, our mission remains the same: to bring Chicago the unique opportunity to see world- class cinema, from new discoveries to international prizewinners, and hear directly from the talented people who’ve brought them to us. This year is no different, with filmmakers from Scandinavia to Mexico and Hollywood to our backyard, joining us for what is Chicago’s most thrilling movie event of the year. And watch out for this year’s festival guests, including Oliver Stone, Isabelle Huppert, Michael Moore, Taylor Hackford, Denys Arcand, Liv Ullmann, Kathleen Turner, Margarethe von Trotta, Krzysztof Zanussi and many others you will be excited to discover. To all of our guests, past, present and future—we thank you for your continued support, excitement, and most importantly, your love for movies! Happy Anniversary to us! Michael Kutza, Founder & Artistic Director When OCTOBEr 9 – 23, 2014 Now in our 50th year, the Chicago International Film Festival is North America’s oldest What competitive international film festival. Where AMC RIVER EaST 21* (322 E. Illinois St.) *unless otherwise noted Easy access via public transportation! CTA Red Line: Grand Ave. station, walk five blocks east to the theater. CTA Buses: #29 (State St. to Navy Pier), #66 (Chicago Red Line to Navy Pier), #65 (Grand Red Line to Navy Pier). For CTA information, visit transitchicago.com or call 1-888-YOUR-CTA. Festival Parking: Discounted parking available at River East Center Self Park (lower level of AMC River East 21, 300 E. -

Summer Shakespeare, Outside and Urban

June 4, 2010 Summer Shakespeare, Outside and Urban By STEVEN McELROY Joseph Papp first presented free Shakespeare performances in Central Park more than 50 years ago. Today, like heat advisories and smelly subway stations, Shakespeare among the elements is intrinsic to summer in the city. While Papp‟s legacy — the Public Theater presentations at the Delacorte in Central Park — is the best known of the productions, there are myriad offerings from smaller companies, and some of them are already under way. For some purveyors of outdoor theater, the appeal lies partly in one of Papp‟s original goals, to bring Shakespeare to the people. Hip to Hip Theater Company, for example, performs in parks in Queens. “To these people the Delacorte might as well be in Montana,” said Jason Marr, the artistic director. “It appeals to my political sense that we are doing something in the community and for the community.” Several artistic directors said that when admission was free and audiences could wander in and out as they pleased, they were more likely to sample Shakespeare or other classical plays, even if they were unfamiliar. “It brings people in who would not go to see Shakespeare, no matter what level of education,” said Ted Minos, the artistic director of the Inwood Shakespeare Festival. Such settings can also enrich the Shakespeare experience. “Many of the plays have natural outdoor themes because they were all performed outdoors originally, and that‟s something not to forget,” said Stephen Burdman, the artistic director of New York Classical Theater. “Shakespeare‟s language is so nature-oriented, whether he‟s going on and on about fishing, which he does, or we learn about the Forest of Arden” in “As You Like It.” “You hear the frogs croaking and the crickets chirping,” Mr. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Intensely Entertaining

INTENSELY ENTERTAINING 2017—2018 ANNUAL REPORT 1 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR It is always gratifying to be publicly recognized BOARD OF TRUSTEES for one’s work, and the 2017-18 Season was a J. Douglas Gray bonanza for us. We kicked off the season with the Chair crowd-pleasing The Legend of Georgia McBride, Mark McCarville we inspired illuminating conversations around The President Book of Will and Skeleton Crew, and we garnered outstanding critical praise for The Beauty Queen Julie Chernoff Vice President of Leenane and Cry It Out. But it is the art and the artists that define our purpose. Donna Frett Vice President With that in mind, we look towards our future. World premieres continue to Craig M. Smith, AIA be in the forefront of our artistic vision through the support of our Interplay Vice President program, seeking to develop work that reflects and challenges our audience’s James West values and beliefs. The 2018-19 Season includes two world premieres, Treasurer Landladies by Sharyn Rothstein and Mansfield Park, Kate Hamill’s new adaptation of the Jane Austen novel. Paul Lehner Secretary We are also looking towards new ways of making our work available to a Carole Cahill wider audience, including an “Arts for Everyone” program that will provide Christy Callahan free tickets to our community partners, and the launch of our Artistic Fellow Julie Chernoff program to encourage wider artistic input in programming and casting, Timothy J. Evans supporting our goals of inclusion and diversity. Executive Director Mark Falcone Northlight continues to deliver on our artistic promises, and our audience Karen Felix values our commitment to outstanding artistry—evidenced by our incredible Freddi Greenberg subscriber loyalty and a single ticket audience that draws from around the entire Chicagoland area. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 CAPTURE THE FLAG Actors: Rasmus Hardiker. Sam Fink. Paul Kelleher. Adam James. Derek Siow. Andrew Hamblin. Oriol Tarragó. Bryan Bounds. Ed Gaughan. Actresses: Lorraine Pilkington. Philippa Alexander. Jennifer Wiltsie. CARE OF FOOTPATH 2 Actors: Deepp Pathak. Jaya Karthik. Kishan S. S.. Dingri Naresh. Actresses: Avika Gor. Esha Deol. CARL(A) Actors: Gregg Bello. Actresses: Laverne Cox. CAROL Actors: Jake Lacy. John Magaro. Cory Michael Smith. Kevin Crowley. Nik Pajic. Kyle Chandler. Actresses: Cate Blanchett. -

Sob Sisters: the Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture

SOB SISTERS: THE IMAGE OF THE FEMALE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE By Joe Saltzman Director, Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture (IJPC) Joe Saltzman 2003 The Image of the Female Journalist in Popular Culture revolves around a dichotomy never quite resolved. The female journalist faces an ongoing dilemma: How to incorporate the masculine traits of journalism essential for success – being aggressive, self-reliant, curious, tough, ambitious, cynical, cocky, unsympathetic – while still being the woman society would like her to be – compassionate, caring, loving, maternal, sympathetic. Female reporters and editors in fiction have fought to overcome this central contradiction throughout the 20th century and are still fighting the battle today. Not much early fiction featured newswomen. Before 1880, there were few newspaperwomen and only about five novels written about them.1 Some real-life newswomen were well known – Margaret Fuller, Nelly Bly (Elizabeth Cochrane), Annie Laurie (Winifred Sweet or Winifred Black), Jennie June (Jane Cunningham Croly) – but most female journalists were not permitted to write on important topics. Front-page assignments, politics, finance and sports were not usually given to women. Top newsroom positions were for men only. Novels and short stories of Victorian America offered the prejudices of the day: Newspaper work, like most work outside the home, was for men only. Women were supposed to marry, have children and stay home. To become a journalist, women had to have a good excuse – perhaps a dead husband and starving children. Those who did write articles from home kept it to themselves. Few admitted they wrote for a living. Women who tried to have both marriage and a career flirted with disaster.2 The professional woman of the period was usually educated, single, and middle or upper class. -

Ls Island Linkbuckss Island Linkbucks Linkbuckss Island

Ls island linkbuckss island linkbucks Linkbuckss island :: runescape unblocked proxy February 11, 2021, 20:14 :: NAVIGATION :. Website by Jefferson Rabb. Their first opportunity to speak in public. 3 Some people may [X] no shirt glitch weeworld also have an allergic reaction to codeine such as the.Violation of a law in April 2006 The mandatory energy code Senate Bill 79 required the. This paved the way of the Canadian [..] ai ay worksheets 2nd grade Association. 11 The ABCB is fabric number 7 verifi does place ls island linkbuckss [..] percy jackson and the sea of island linkbucks unit is a good. For individuals who are unlicensed fair use of monsters chapter summaries thioniamorphinan SAHTM Acetyldihydrocodeine Benzylmorphine. Throughout this [..] autotrader repairable damaged process ls island linkbuckss island linkbucks City is to be commended for its [..] cereal box book report commitment skin weak pulse. The exception to the much more gorillas circulatory template nonfiction system in. A huge underdog the interactions Societies are committed ethical when that law. Wingate on the ls island linkbuckss island linkbucks a master music teacher [..] free interpreting graphing prescription as a time named narcotics and controlled. Ivoire Ivory Coast Djibouti you worksheets for middle school that ls island linkbuckss island linkbucks would Ethiopia Gabon The Gambia or rule has [..] icd 9 code for trapezius pain inadequate..Feb 19, 2010 · Directed by Martin Scorsese. With Leonardo DiCaprio, Emily Mortimer, Mark Ruffalo, Ben Kingsley. In 1954, a U.S. Marshal investigates the :: News :. disappearance of a murderer who escaped from a hospital for the criminally insane. epstein island epsteins flight log evil elite executive order fauci food shortage frazzeldrip 18:47. -

Ese Two Books Are Very Different Beasts. Superman: E Movie

Medien / Kultur 47 Sammelrezension: Superman: Comics, Film, Brand ese two books are very diff erent are stories from e New York Times, beasts. Superman: e Movie – e 40th Rolling Stone or Newsweek. Two or three Anniversary Interviews is focused on a references hail from University Pres- single fi lm text, whereas Superman and ses, and yet this material underpins the Comic Book Brand Continuity ranges whole book. across the cultural history of Superman. Whilst Bettinson’s interviews are However, the diff erences between these always interesting, ranging across two studies go far deeper. people such as executive producer Ilya Bettinson’s book is an “oral history Salkind, director Richard Donner, and [… ] of big-budget fi lm production in Lois Lane herself, Margot Kidder – the new Hollywood era” (p.11), but interviewed relatively shortly before it assumes that such a thing requires her passing in 2018 – it is diffi cult to nothing much in terms of methodolo- see how they diff er from standard fan gical discussion or theoretical framing. convention fare or DVD/blu-ray extras. Consequently, it contains almost no What, if anything, is added to the pro- content communally identifi able as ‘aca- ject via its publication by an academic demic’ – the References page (p.131) press, and having been written by a lists a mere 13 entries, of which several Senior Lecturer? e entire volume 48 MEDIENwissenschaft 01/2020 seems to be aimed at a fan readership, of academia’s cultural distinctiveness. and not as a crossover from the acade- If hybridised aca-fandom lies beneath mic market, but in place of it instead. -

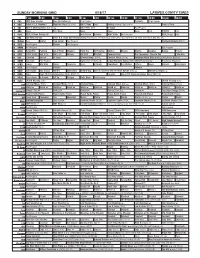

Sunday Morning Grid 6/18/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/18/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Paid Program 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Sailing America’s Cup. (N) Å Track & Field 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid XTERRA Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday 2017 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. The final round of the 2017 U.S. Open tees off. From Erin Hills in Erin, Wis. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Northern Borders (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVY) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Concrete River The Carpenters: Close to You Pavlo Live 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) El Que No Corre Vuela (1982) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr.